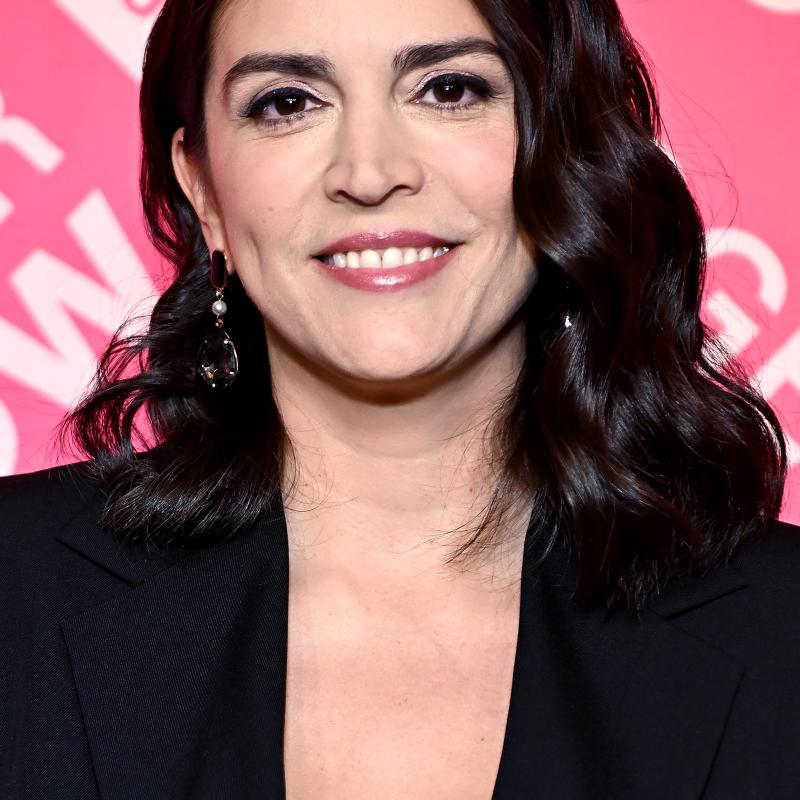

Singer and Actress Audra McDonald.

Singer/Actress/Performer Audra McDonald. McDonald has won three Tony Awards, for her performances in ‘Carousel,’ ‘Master Class,’ and ‘Ragtime.’ She recently performed on Broadway as the star of ‘Marie Christine,’ and just appeared in The Vagina Monologues at the Westside Theater in New York. She continues to appear on concert stages nationally. Her new CD is called ‘How Glory Goes’ (Nonesuch Records), and her PBS Special, ‘Audra McDonald at the Donmar, London,’ is airing nationally in March. (This interview continues in the second half of the show.)

Other segments from the episode on February 29, 2000

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: FEBRUARY 29, 2000

Time: 12:00

Tran: 022901np.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Interview With Audra McDonald

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:06

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

My guest, Audra McDonald, is the most acclaimed Broadway singer in years. She won Tony awards for her first three Broadway roles, in "Carousel," "Ragtime," and "Master Class," and that was before reaching the age of 30.

"Boston Globe" music critic Richard Dyer described her as having "a classical singer's breath support, a jazz singer's sense of phrasing, a Broadway singer's theatrical intensity, and a gospel singer's soul-shaking conviction."

"New York Times" critic Stephen Holden described her new CD as having "as lofty a vision of nonclassical American theater music as any singer has dared put forth."

That CD is called "How Glory Goes," and it features classic Broadway songs, as well as songs by today's new music theater composers. Composers seem to love to writer for her. In fact, she recently starred in "Marie Christine," a musical written for her by Michael John LaChiusa.

Before we meet Audra McDonald, let's hear a track from "How Glory Goes." From the musical "West Side Story," this is "Somewhere."

(AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, "SOMEWHERE," BERNSTEIN'S "WEST SIDE STORY," AUDRA McDONALD)

GROSS: Audra McDonald, welcome to FRESH AIR.

AUDRA McDONALD, "HOW GLORY GOES": Hi, Terry, thank you.

GROSS: Now, I know you were trained at Juilliard. Why did you decide to head in the direction of Broadway, as opposed to either opera or art song?

McDONALD: That's basically because when I started out as a performer back in Fresno, California, where I was raised, I had only one goal, and that was to be on Broadway. And then I decided to audition for a couple of schools, and I got accepted at Juilliard. And I thought, Well, I can't turn them down, I have to go.

But I don't think I quite understood how incredibly rigid and classical my training would be at Juilliard. I think I was still very naive. And I thought that I would get a chance to perhaps, you know, go out and audition for Broadway shows or take a couple of acting classes, dance classes, et cetera. That's not how the program was structured at that time.

So after I finished Juilliard, I just sort of headed back towards the direction that I had originally wanted to be in, and that was, you know, heading towards Broadway.

GROSS: When you got to Juilliard, did the teachers have you sing in ways that you resisted because you were used to Broadway and not classical music?

McDONALD: Yes. I was constantly being told to, you know, not scoop your notes, not slide, not to lose the tone of the sound because you're getting so emotional about something, you know, to sort of -- I guess clean up my act, you know. I'm trying to think of a good way to put it. But -- so I resisted for a long time, and it wasn't till I got into my French diction class that I sort of discovered the French repertoire, and I discovered that that spoke to me in a way that Broadway music had spoken to me, and was able to sort of find my way into classical music through the French repertoire, basically.

GROSS: What was it about the French repertoire that spoke to you?

McDONALD: Well, it was the later French repertoire, Poulenc and Faure. Especially with Poulenc and even a bit with Satie -- you know, Satie was (inaudible) the father of the Dadaist movement, so he was very into just really absurd poems and whatnot. And I enjoyed singing about things like frogs.

And then with Poulenc, that had to do more with the harmonic language. There was a lot of jazz influence, and I just found the music so incredibly beautiful, and the poems that he chose so incredibly beautiful, that I was able to sort of immerse myself in an emotional place in that music. And that's where I all of a sudden was able to find my classical voice.

GROSS: So do you think you'll ever sing opera?

McDONALD: Yes, I do. I don't know when that'll be. As I've gotten older, I've noticed my voice has gotten a bit more operatic, and as it continues to mature, that's the neat thing, I think, about being a singer, is your voice continues to mature as you grow. And it's usually not in its full form until your mid-30s, sometimes even later for some people.

So I can imagine myself doing it in years to come. I don't think I'm quite there yet. But, you know, I -- never say never.

GROSS: Why don't we hear another song from your new CD, "How Glory Goes"? And I thought we could hear "Bill," the song from "Showboat."

McDONALD: Yes.

GROSS: And this is Kern and Hammerstein. Tell me why you selected this song, a great song, I think, by anyone's standards. Why did you want to sing it on this CD?

McDONALD: I started performing this song in concerts and stuff that I was doing around the country, and I had always loved the song, and I loved Helen Morgan, and I -- you know, I loved "Showboat," and I loved the entire score. And in choosing material, I usually choose songs very quickly. When my music director brings songs to me, or if it's a song I hear, I can usually decide within four measures of the song that I want to do it. It just -- there's an immediate gut reaction.

And that's how I felt with "Bill," and just the fact that it spoke so much to my own sort of personal Valentine to my fiance. It feels like that's what it is to me, which is why I'm so emotional about this song.

GROSS: Well, this is "Bill" from Audra McDonald's new CD, "How Glory Goes."

(AUDIO CLIP, "BILL," FROM KERN AND HAMMERSTEIN'S "SHOWBOAT," AUDRA McDONALD)

GROSS: That's Audra McDonald singing "Bill" from "Showboat," and that's on her new CD, "How Glory Goes."

Now, I was reading about you that when you were young, and I guess auditioning for community theater and things like that, that your parents urged you not to audition for "Showboat."

McDONALD: They were adamant. It wasn't just encouragement, they were adamant. They did not want me to be, you know, playing a stereotypical version of what a black person was at that time. They weren't interested in that for me. They said, you know, You can sing the music, you can do the little pre-shows before "Showboat," but we don't want you doing that show.

They just said there were plenty of other things that I could do, and I didn't need to do that.

GROSS: Do you think in "Showboat" you would have stood any chance of getting the role of Julie, who is a light-skinned African-American who passes for white during the first part of the show, and eventually gets to sing "Bill"?

McDONALD: Right. What -- well, obviously not at that time, I wouldn't have gotten the role. I don't think I would have been able to actually ever play that role, because I think I'm a little too dark-skinned, actually. I don't think I could ever really pass for looking white. But it's a role that I would love to have played, actually, because the character is incredible.

GROSS: When you were young, growing up in Fresno, California, and loving Broadway, did you worry about what roles you would get as an African-American?

McDONALD: I did, I did. I remember when I was in high school hearing about the revival of "Dream Girls" that had taken place, and I was devastated, because I thought, Oh, well, if it's being revived now, what's going to happen when I get to New York? There's not going to be anything for me to be in, you know, I was very worried that, you know, there wouldn't be really any shows for me to do.

And even in Fresno, California, because our dinner theater was very small, I auditioned for everything that I thought I was right for. And actually there was some pretty controversial casting that went on. I played Eva in "Evita" at the age of 16, and there were some -- there was a bit of controversy even in the town over that, over me getting that role.

So -- but it was a major concern growing up.

GROSS: Well, your big breakthrough on Broadway came at the age of 23, I think it was, when you got the part of Carrie in "Carousel." And this was a revival in New York, you know, a very acclaimed revival. And Carrie is the character -- she's, like, the best friend, and she gets to sing "When I Marry Mr. Snow."

McDONALD: Right.

GROSS: And you won a Tony for this, and you -- I mean, you got rave reviews, you won a Tony. It was your first Broadway performance. This has -- this is always a white role. Was it -- were you surprised that you got the part? I mean, did you even expect to be able to get an audition for it?

McDONALD: It's funny, when it -- when the auditions happened, I knew that they were looking to fill, you know, the -- they had the entire cast to fill. And I thought, Well, you know, they'll -- I'm sure they'll be interracial about casting the ensemble, you know, I thought that would, you know, be a place, and that's what I was hoping for, actually, at that point. I was thinking, Wow, and maybe they'll let me cover one of the leads, you know.

And the more and more they called me in, the more I started to think this could possibly be a reality, simply because Nicholas Heitner (ph) had done this production in London at the National Theatre, and had cast a black man in the role of Mr. Snow. And so I knew that he was certainly thinking that it could possibly -- it could be a possibility.

And so, like I said, the more and more I auditioned, the more and more I thought, This is something that could be very real. And, I mean, in the end, of course, I was shocked that I actually got the role. But I wasn't shocked that he had cast a black person in it, by that point I wasn't, because I knew that he was thinking of doing that. I was shocked that it was me.

GROSS: Now, I want to get back to your parents' advice of not doing stereotyped roles, and not auditioning for "Showboat." Was it good advice, in retrospect?

McDONALD: I think it was in retrospect, just because there were other things at that time that I could do. And I understand where they were coming from. You know, my mother was raised in the South in the '50s, and the segregation was still very much part of her life at that time.

And, you know, they didn't want us to have to go through that in any way, shape, or form. And to portray it on stage was, I think, just sort of a nightmare option for them. I just think they thought that -- why do that when there are other things? We've worked so hard to get past this, that there are other things you can do.

So in retrospect, I think it was a good idea just because it taught me to not settle for certain roles, or to not look at myself as someone who could only do such-and-such type of roles because of -- or could be limited by my color. I think that's what maybe it taught me, to not feel that I -- my color limited me.

So it probably was good advice. At the time, I was upset. I was upset, because I didn't get it, you know, I was only 10, I didn't get it.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is singer Audra McDonald. Her new CD is called "How Glory Goes." Let's take a short break here, and then we'll talk some more and hear more music.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

GROSS: My guest is singer Audra McDonald, a three-time Tony award winner. She has a new CD called "How Glory Goes," in which she sings the work of old and new Broadway composers.

Let's get to one of the new composers whose work you sing. And this is a song by Adam Guettel, and he -- you included him on your first CD, he's included you on his CD of songs. How...

McDONALD: Mutual admiration society. Go ahead.

GROSS: Yes, how did you first meet him?

McDONALD: I...

GROSS: I should mention too, he's, what, the grandson, is it of Richard Rodgers?

McDONALD: Of -- yes, he is Richard Rodgers' grandson. Adam Guettel and I met backstage one night after his show "Floyd Collins" at Playwrights' Horizons. My fiance was playing in the orchestra at the time and had been telling me about this show. And I saw it, and Washington so blown away by the music and so blown away by the show and the performances that I was speechless afterwards. And basically was just a pile of jelly when I actually did meet him.

And then I went back and saw the show, like, 65 times. I call myself their biggest fan. And after that, he asked me if I wanted to do a workshop of his called Myths and Hymns, and, you know, which later became the CD. So that's how we started working together and how we got to know each other, although, you know, I knew his mother, because his mother, Mary Rodgers, was part -- you know, part of the casting for "Carousel." So she was at a lot of my auditions for "Carousel," actually, so...

GROSS: Why, because it's a Richard Rodgers musical.

McDONALD: Of course, yes, yes.

GROSS: OK, well, why don't we hear you singing "Was That You?" from your new CD. And this is a song by Adam Guettel and Lindy Robbins. I assume Lindy Robbins wrote the lyric?

McDONALD: Mm-hm.

GROSS: OK, here it is.

(AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, "WAS THAT YOU?" BY GUETTEL AND ROBBINS, AUDRA McDONALD)

GROSS: Audra McDonald from her new CD, "How Glory Goes."

Audra McDonald, what is special to you about singing the work of composers who are alive now? I mean, you can't ask Richard Rodgers what he had in mind when he wrote a song, but you can ask Adam Guettel what he had in mind when he wrote a song.

McDONALD: Well, I think you just hit the nail on the head right there, that's it. It's much more of a collaborative effort, because they're sitting right there, and especially in cases like Adam Guettel and Michael John LaChiusa, where they have written songs with my voice in mind. It's like having a dress completely tailor-made for you. It's an incredible experience.

Also, because we are contemporaries, I feel that I can get into the head of their songs a little bit better, because, you know, there are issues that, you know, are -- that I'm dealing with, or that we've dealt with, or, you know, we're all around the same age, and so we're all sort of going through the same things right now.

I mean, for me, even with the song "Was That You?" which just is about someone saying, And is it just that I want to be in love so much that I've projected this whole thing onto this person, or do I really love you? I mean, I know that's an age-old story, but just the way it's presented feels very contemporary to me.

You know, or with a song on my last album, like -- as controversial as it may have been to some people, the song "Come to Jesus" that Adam wrote, you know, where there's a couple dealing with not only a breakup but an unwanted baby and an abortion, I mean, a lot of things that are quite topical, quite -- they're sort of modern issues that you wouldn't have been singing about, you know, not even -- I don't think 20, 30 years ago.

GROSS: You talked about how great it was to have a song written for you, as kind of like having a dress tailor-made for you. You just had a whole show (laughs) written around you, "Marie Christine," which is by the composer Michael John LaChiuso.

Do you have any sense of what qualities of your voice the score was written around? Was it your range that was taken into account, the colors of your voice?

McDONALD: Yes, because Michael John knows my voice as well as he does, he was able to take advantage of specific parts of my voice to communicate musically whatever emotions I needed to communicate.

He had me singing very high and quietly when I was, like, serenading my children, and when I was being very motherly. He had me down in the gutter when I was angry, you know, in the gutter of my voice, you know, way down in the chest where it gets gritty, and just so he could really, you know, show that color, that angry color, and had me sort of in the middle range, in the sort of -- right at the passagio part, when I was singing about love or singing about being in love.

And so -- and he actually also knows what he calls my -- I know where your money notes are. So he always goes to them (laughs) for, you know, when he really wants to emphasize something. So he knew my voice well enough to know where to take it to express what he needed to express with the character.

GROSS: Audra McDonald's new CD is called "How Glory Goes." She has a PBS special featuring her in concert that will be shown in March. She'll be back in the second half of the show.

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(AUDIO CLIP, SONG EXCERPT, AUDRA McDONALD)

(BREAK)

GROSS: Coming up, we continue our conversation with Audra McDonald.

And we talk with former NBA star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar about coaching a high school basketball team on an Apache reservation. He just accepted his first professional coaching position with the Los Angeles Clippers.

(BREAK)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross, back with singer and three-time Tony award winner Audra McDonald. She has a new CD called "How Glory Goes" featuring classic Broadway songs and songs by contemporary music theater composers.

You must have a lot of people wanting to pull you in different directions now. I mean, you are really in demand. So do you have to figure out, like, Who am I? before trying to decide, you know, who you want to be for other people?

McDONALD: That has been a struggle for me lately, because there are many opportunities that I have been afforded in the past, and there are doors now opening on all sides. And it's -- you want to do something well, and if you spread yourself too thin, you end up not being able to -- you know, you become, you know, the jack of all trades, the master of none.

So I really have to force myself to listen to my gut when it comes to choosing a project, whether it be, you know, a recording project or a show, you know, an operatic piece, whatever. I really have forced myself to learn just to listen to that inner voice saying, Oh, I don't feel -- this isn't right for you, you know, even though everybody else is saying, Oh, but it's a career move, you need to make it.

Everybody thought I was crazy doing "Ragtime." They said, Why are you going to do that? You don't need to go back to Broadway just yet. You should try to find a TV series or this or that. Everybody thought I was crazy for doing the album, the first album, and choosing just new composers. Well, no one's going to buy that, you know, (inaudible) just do old standards, don't do the new composer thing. Who's going to listen?

You know, so a lot of times I don't necessarily go with what everybody thinks I should do but rather what's sort of inside.

GROSS: I want to play you singing another song, and this is actually from the sound track of the movie "The Cradle Will Rock," the movie about the making of the musical "Cradle Will Rock" by Marc Blitzstein. And this is a terrific performance, and I think it shows off a different side of your voice from what we've been hearing. And this is a much kind of, like, deeper, angrier side of your voice.

The sound is called "Joe Worker." Would you say something about the style that you're singing in on this?

McDONALD: Well, this is a very -- this is very chesty. I don't go into my head voice at all with this song. And Tim Robbins was in the studio when I recorded it, and pushing me further and further to, he said, really make sure you were visualizing everything that you were singing about, which is something I try and do all the time. But he said, I really want you to imagine these hungry, angry, embittered, you know, hurt people. And I really want to hear that in your voice.

So he really pulled a dramatic performance out of me with this one. You know, he wasn't coming at me with, you know, vocal notes, make this sound prettier, you know, he was really saying, Forget pretty, go for the -- you know, what the piece is saying.

GROSS: And so this is "Joe Worker" from the sound track of "Cradle Will Rock," which was directed by Tim Robbins. And here's Audra McDonald singing "Joe Worker."

(AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, "JOE WORKER," FROM BLITZSTEIN'S "CRADLE WILL ROCK," AUDRA McDONALD)

GROSS: Audra McDonald from the sound track recording of "Cradle Will Rock."

I was very interested in what you were saying Tim Robbins told you, you know, don't worry about pretty, he didn't want pretty. I bet that's not advice you often get, because you have such a beautiful voice.

McDONALD: Well, no, it isn't advice that I often get, although the same thing with "Marie Christine" certainly applied, you know, where it was more about finding the dramatic moment and really going with that moment, and not -- you know, it's -- which is, I think, in some cases can be quite opposite from, like, a more classical sound, where it is about -- you do worry about pretty, you do worry about the purity of the tone.

Whereas with this, that you worry about the purity of the drama and the purity of the moment in terms of telling the story. And in "Marie Christine," I made some very ugly sounds, but they were right for the character. You can't make a pretty sound and then kill someone, you know. It's just not...

GROSS: Right, your character was based on the character in "Medea," who basically prepares her children for dinner (laughs) and serves it to her husband.

McDONALD: Along with a lot of other people. (laughs) So, yes, I mean, in those cases. And those are things that I love, you know, I -- not the murdering part, but I really enjoy, you know, chewing on a great juicy sort of script and character that you can really get into, and then paint the character with your voice. I think that's, you know, one of the reasons why I do it, because it's -- I find it so fulfilling.

GROSS: Now, I want to talk a little bit about your background. I believe your father was the principal in your high school when you were in high school?

McDONALD: He was the -- no, he was the principal of my summer school high school. He was the principal at another high school, but he always got my report cards before I did, because he was in the school district, so he could get them. (laughs) And make sure they were right and make sure they were good.

GROSS: And were they?

McDONALD: Oh, yes, we were good students. My sister and I were very good students. You know, my parents were both educators, and were, you know, firm believers in being solely responsible for your own advancement. So to do that, you had -- they -- you know, they used to tell us, You have to be not just qualified for a job but overqualified for a job. You know, you have to work twice and thrice as hard, because people will want to keep you a little further back because of your color. So you must work harder so that they have no choice but to hire you, you know.

GROSS: Did you go to public school?

McDONALD: I did.

GROSS: Was it a good school?

McDONALD: I went to a performing arts high school that was a public school. It was a part of a magnet program that they were doing in Fresno to stop forced busing, basically, and let the students decide where they wanted to go based on, you know, what the school specialized in. So there was a computech school, there was a performing arts school, there was a school for polytechnical, for agricultural things. So people could choose.

You know, I'm interested in the arts, I'll go the performing arts school. I'm interested in computers, I'll go to the, you know, computer school. Which was a great way to sort of still desegregate the school system but without forcing busing.

GROSS: Now, I understand you were diagnosed as being hyperactive when you were a kid. How old were you when you got that diagnosis?

McDONALD: Eight or 9.

GROSS: What were you doing in the first place that made people suspect hyperactivity?

McDONALD: What wasn't I doing? I was very dramatic, and I would overreact to basically anything. A thunderstorm would become a monsoon to me, and I would trip and fall, and you would think that I had basically, you know, cut my head open and was bleeding to death. I was just very emotional and overreacted. I had a hard time when I first went to school. I felt that I just was a very hyper -- and hypersensitive.

And so the doctor just said, Well, she's got a lot of energy, and find a way to channel it, instead of, you know, medicating her. That doesn't make sense. Just find a way to channel it. And they knew that I loved to sing, and we had piano lessons, and I had dance lessons as a youngster. And then they found this junior company group that I auditioned for when I was 9, and I stayed with that company, which was also the dinner theater, until I graduated from high school.

GROSS: When you were growing up in Fresno, did Broadway seem very far away?

McDONALD: It did, and it didn't. It felt far away in that, you know, I understood that there was 3,000 miles between Fresno and New York, but it didn't in that I was single-minded of purpose. That's all I wanted. And so I was doing everything I could to prepare myself for that, you know, to make that journey. So because I think my focus was so, you know, razor-sharp in terms of, you know, wanting to be a Broadway star, it didn't feel far away. You know, it just felt like, these are the steps I need to take to get there.

Which is why, actually, for me when I got to New York and started to go to school at Juilliard, Broadway felt further away from me than it ever had before. And I was literally on the street, you know. But all of a sudden I was heading in the wrong direction in terms of where my education was taking me.

GROSS: Do you think that your teachers at Juilliard actually did you a favor by forcing you -- you know, insisting that you learn classical music techniques? Or do you think that...

McDONALD: Oh, yes.

GROSS: You do.

McDONALD: Yes, I do. Because I think I now have a technique that will sustain me and help me to have, hopefully, a longer career than I necessarily would have had, had I not known how to take care of my voice. And also, if I hadn't of gone to Juilliard, I couldn't have done "Master Class," you know? That was a role I was...

GROSS: The -- the -- the -- the Broadway show, yes.

McDONALD: The Broadway show "Master Class," in which I was playing, you know, a student at a conservatory who was singing classical music. So I don't regret having been a student at Juilliard by any stretch of the imagination. But I do admit to the fact that it was very difficult while it was going on. But it's like, you know, eating your vegetables, you're supposed to (inaudible).

GROSS: So what's next for you? What are your next projects?

McDONALD: I am going around the country for the next couple of months performing my -- sort of like -- not one-woman show, but just a little concert that I do with a trio, and doing songs from my new album and my old album. And then I'm learning, actually, "The Seven Deadly Sins," which I'll be performing quite a bit over the next year.

GROSS: The Kurt Weill musical.

McDONALD: Yes, and very -- I'm very much looking forward to working on that. That's what I mean by, you know, taking my time tip-toeing into the operatic realm, you know. And this is a -- sort of another good bridge, you know.

GROSS: Right, yes.

McDONALD: Looking forward to that.

GROSS: Well, I want to thank you so much for talking with us.

McDONALD: Oh, my pleasure, Terry.

GROSS: Audra McDonald's new CD is called "How Glory Goes." She has a PBS special featuring her in concert that will be shown in March.

Coming up, former NBA star and new assistant coach of the Los Angeles Clippers, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, talks about coaching a high school team on an Apache reservation.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia, PA

Guest: Audra McDonald

High: Singer/Actress/Performer Audra McDonald. McDonald has won three Tony awards, for her performances in "Carousel," "Master Class," and "Ragtime." She recently performed on Broadway as the star of "Marie Christine," and just appeared in "The Vaginia Monologues" at the Westside Theater in New York. She continues to appear on concert stages nationally. Her new CD is called "How Glory Goes," and her PBS Special, "Audra McDonald at the Donmar, London," is airing nationally in March.

Spec: Audra McDonald; Entertainment; Music Industry

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 2000 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 2000 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Interview With Audra McDonald

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: FEBRUARY 29, 2000

Time: 12:00

Tran: 022902NP.217

Type: FEATURE

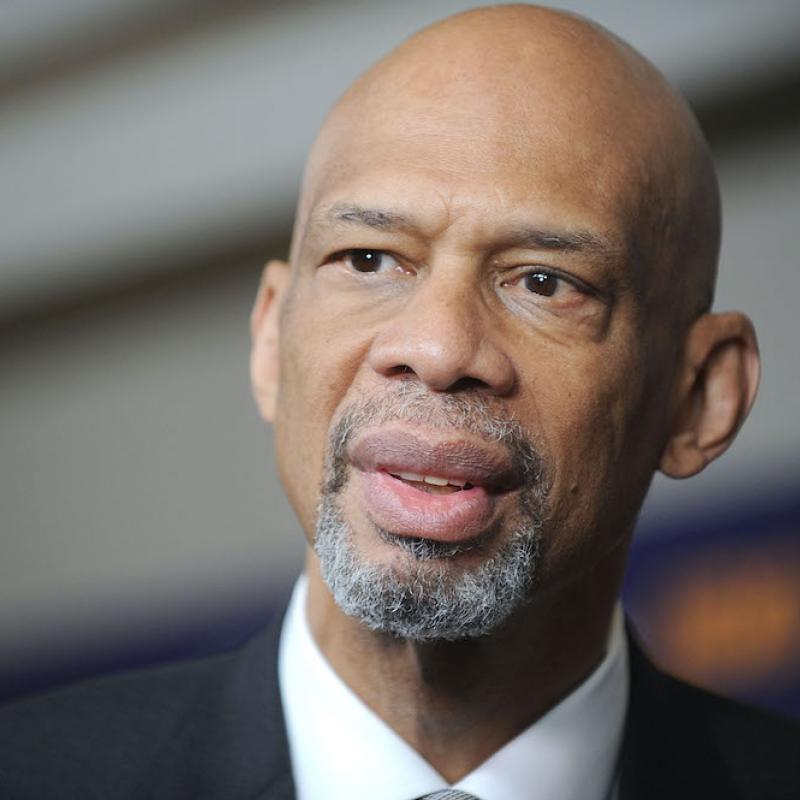

Head: Interview With Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:30

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Last week, former NBA star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was named assistant coach of the Los Angeles Clippers. Abdul-Jabbar was a six-time NBA most valuable player and two-time scoring champion.

The Clippers is the team with the youngest players and the worst record in the NBA, but it's a start. Abdul-Jabbar has wanted to coach for a long time, but was unable to land a position, with one exception. In 1998, when he was 51, he was invited to be an assistant coach of a high school basketball team on the White Mountain Apache Reservation in Arizona, where he already had friends.

Abdul-Jabbar collects artifacts of the American West and has a special interest in the Buffalo Soldiers, the African-American cavalry regiment formed after the Civil War.

The high school couldn't even afford to pay him, but it offered something he needed more at the time, an opportunity to find out if he had the temperament and dedication to coach. He writes about his stay there in his mew memoir, "A Season on the Reservation."

I spoke with him a few days before he joined the Clippers. He says that when he first watched the Apache team play, he saw a lot of bad habits, including the players' emphasis on running.

KAREEM ABDUL-JABBAR, "A SEASON ON THE RESERVATION": Well, it's one thing to run under control and have a purpose, and that's what the running game is all about in basketball. But to run just to be running, and to see what happens, is not usually the way the game is played, and that's how they did it. They just got the ball down the court any way they could. Didn't matter if it was a pass or if it went off somebody's shoulder. (laughs) Just -- they got the ball down the court and threw up the shot, and then ran down the other end and did the same thing. And that was the way that they played the game.

GROSS: Something else you noticed, they not only didn't talk trash on the court, they were almost mute on the court. And you thought that that was a real problem.

ABDUL-JABBAR: Oh, yes, the lack of communication between the players on the court was really something that really startled me. Every good basketball team is a team that communicates well, and they understand what they want to do on offense and defense, and they talk to each other about it as things happen, as things unfold.

And the Apache kids were completely silent. It was rare that you heard them say anything to each other on the court. Most of what you heard on the court was -- would come from the coach telling them to do specific things or run a certain play.

GROSS: Now, what about the cultural differences? Did you think at any point, Well, the fact that they're quiet on the court, that they don't communicate well, is that a kind of cultural thing?

ABDUL-JABBAR: It certainly is a cultural thing. The Apaches appreciate silence. You know, they spent a lot of time in the past century setting ambushes, whether as hunters or as warriors fighting other tribes or fighting the U.S. Cavalry. And silence and stealth is an Apache trait that served them very well. And it's part of their folklore.

So that is something that comes naturally to them and makes them a little bit tough to coach when you got to get people talking to each other on defense, and talking to each other when they try to set up an offensive play.

GROSS: So how did you handle that? You know, being respectful of the history of silence and stealth, and yet saying, Look, it's the court, you know, you really got to communicate.

ABDUL-JABBAR: My approach was to let them know how it helped them, to tell them why they needed to do this in order to help their game, and so that we could have an advantage. And it started to improve a little bit. At certain times in practice, something would happen, and I was able to make a point here or there and start the ball moving in terms of them learning a different way of doing things.

GROSS: Now, you point out that a lot of the players on the team had a lot of personal problems that reflected larger problems on the reservation. There was a lot of alcoholism on the team, as there was on the reservation. A lot of the kids had family problems at home that were reflected in their performance on the court. Were these problems that you were used to from your own high school or from, you know, the lives of other players you had worked with in the NBA?

ABDUL-JABBAR: Well, not necessarily my own high school days, but, you know, I'm from a part of New York City called Harlem, and the things that -- the negative things that affect Harlem are the same things that affect the kids on this reservation, substance abuse, lack of a good educational system, very few economic opportunities, a history of defeat.

There are a lot of things that are similar that drive people to do self-destructive things. And these things affect people in any disadvantaged part of America. Doesn't matter if it's the ghetto or barrio or Appalachia. These things are common, and they have the same effect on people and families.

GROSS: You describe one of the coaches as having had problems being a good disciplinarian because he was also the kids' guidance counselor, and he had to deal with the kids' home problems, their drinking problems, and self-esteem problems. And it was hard for him to discipline them.

What was your approach to disciplining kids who were having personal problems?

ABDUL-JABBAR: Well, I didn't want them to feel that I'm here to persecute you. That gets nothing done and only makes enemies. I tried to let them know that this was constructive criticism. I tried to improve their play and show them that if they did some of the things that I told them to do the way I did it, they would win more games, and they would have more fun playing the game.

And it took awhile before that got through to them. They just weren't ready to accept it. And, you know, they figured that I'd be gone at the end of the season, and, you know, they could continue doing it the way they wanted to do it.

GROSS: You say no coach ever spared your feelings, if the coach believed that criticizing you would make you a better player. I'm wondering what things you really appreciated from the coaches that you had had, and what things you really wanted to do different from the coaches you had had.

ABDUL-JABBAR: I had really great coaches in high school and college, which is the two areas that are most crucial for the basketball player in becoming better. And I had really good men coach me at that -- at those times of my life. And consequently, I benefited from it.

GROSS: You say you didn't like coaches who tried to push your emotional buttons. Like what?

ABDUL-JABBAR: You get coaches that tell you that so-and-so's coming, and he's going to make you look bad. You know, that's a direct challenge to your pride. I always was self-motivated and did not need to have people tell me that so-and-so was coming to try to make me look bad. I understood that instinctively, and I always tried to prepare myself to be at my best.

GROSS: What about the high school players you were coaching? Did you think that they were self-motivated?

ABDUL-JABBAR: Their motivation wasn't necessarily to be the best basketball players they could be. For them, playing basketball had a lot of social significance, you know, being on the team was a feather in their cap, so to speak, pardon the pun.

GROSS: Status?

ABDUL-JABBAR: Yes, status, prominence, you know, just -- the attention that they got from being on the team, that that would be part of it. A lot of them didn't really think that they needed to improve anything, and getting them to understand that they -- everybody can improve. And it took a while.

GROSS: So how did you motivate them, in addition to trying to show them that your approach might improve their game? Did you punish certain kids or have them do push-ups or, you know, run around the court, or...

ABDUL-JABBAR: Yes, I had them -- For, like, things that I kept harping on them about, and then they kept doing it, finally I got to the point where, you know, when they would make the transgression, I'd have them hop down and give up five push-ups, you know, that -- being singled out like that, they didn't want to do that. And as a group, they started to try to eliminate certain mistakes.

GROSS: You say that Apache boys are particularly sensitive to criticism, and they don't like to be separated from the group, or singled out for any reason. So did that have -- did that -- did you try to be, like, more sensitive to that when you singled somebody out for sloppy moves on the court, or where you singled somebody out and told them they had to do five push-ups, or did you think, you know, the heck with it, it's my job to make them better players, and I'll single them out?

ABDUL-JABBAR: Well, I went on ahead and singled them out, but I didn't do it in a roughshod way. I didn't try to be abusive or, you know, mocking in my criticism. You know, I had a reason to do it, and it was to improve their play, and hopefully to improve the prospects of the team in the post season. That's what everybody was focused on, on trying to win the state championship.

So in order to play at the higher levels, you got to do things a certain way. You can't do it the way that maybe you've learned and thought was OK, and then, you know, you go play against the kids from the city who practice the way everyone else practices. You're at a disadvantage. And I tried to prepare them for that.

GROSS: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, recorded a few days before he was named assistant coach of the Los Angeles Clippers. His new memoir is called "A Season on the Reservation."

(BREAK)

GROSS: My guest is Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and his new memoir, "A Season on the Reservation," is about the season that he spent coaching a high school team on an Apache reservation. And that season was 1998 to 1999.

You say you wanted to teach the essentials to the kids you were coaching, and that you felt the approach you'd been taught was fading. What are some of the things that you felt really weren't being taught in the schools any more?

ABDUL-JABBAR: Well, for one thing, the tall players aren't being taught how to play closer to the basket with their back to the basket. That's a dying art in the game. We only had one really tall player, so that wasn't that crucial that we get him up to speed. He did do some work, and he did do some improvement. But it really came too late.

But just the way the game is played, you have to learn how to be ambidextrous in handling the ball, you have to know how to get your shot off in traffic, you have to know how to look for your teammates, you have to know how to help your teammates on defense. And these were areas that they were not up to speed in, not that they were the worst in the state, but if they wanted to be the best in the state, they really had to improve those things.

GROSS: Did anything surprise you about the games themselves, you know, and the -- how many people would turn out for them, how important basketball was on the reservation?

ABDUL-JABBAR: I knew that the game was very important to the people on the reservation, but I didn't really get a chance to see it in action until I was actually going to the games. These people would drive three or four hours in one direction to see their high school team play, you know, and these are people who don't -- they don't have a lot of money, they don't have a lot of wealth and leisure time. Yet they made a sacrifice to support the team. It was that important to them.

GROSS: The team that you were coaching competed for the state championship but lost. But you think that the season was successful by several other measures. What were the ways that you were measuring the team's success?

ABDUL-JABBAR: Well, we got through the whole year, no one got suspended for substance abuse. No one was academically declared ineligible, because a D, and you can't play, D on your report card, you can't play. And I went to graduation in May, and it was the largest graduating class that they'd ever had. They put the largest amount of kids into colleges and the military services that had -- it was the largest amount of kids that had ever made that transformation.

So, you know, I could take some credit for that with the basketball team, and, you know, I felt that the basketball team really did a good job doing what it was supposed to do.

You know, I really -- initially going there, I thought it was going to be about hoops. I would help them deal with that old thing and improve what was happening on the court. But teaching them what it meant to have a successful life and how to move on and do well in life really ended up being the principal purpose of my being there.

GROSS: Well, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, I want to thank you so much for talking with us.

ABDUL-JABBAR: It's my pleasure.

GROSS: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, recruited (ph) a few days before he was named assistant coach of the Los Angeles Clippers. His new memoir is called "A Season on the Reservation."

FRESH AIR's executive producer is Danny Miller. Our senior producer today was Roberta Shorrock. Our engineer was Audrey Bentham. Dorothy Ferebee is our administrative asssitant. Ann Marie Baldonado directed the show.

I'm Terry Gross.

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia, PA

Guest: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

High: Basketball legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, talks about his new book, "A Season on the Reservation: My Sojourn with the White Mountain Apache." In 1998, a member of the Native American tribe, the White Mountain Apaches, asked Abdul-Jabbar to coach the high school boys basketball team on the reservation. A Season on the Reservation tells the story of his time with the team. Since retiring from the NBA in 1989, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar has appeared on TV and in films, worked with numerous charitable organizations, and authored 3 other books. Earlier this month, Abdul-Jabbar was named the new assistant coach for the Los Angeles Clippers.

Spec: Sports; Kareem Abdul-Jabbar; Youth

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 2000 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 2000 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Interview With Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.