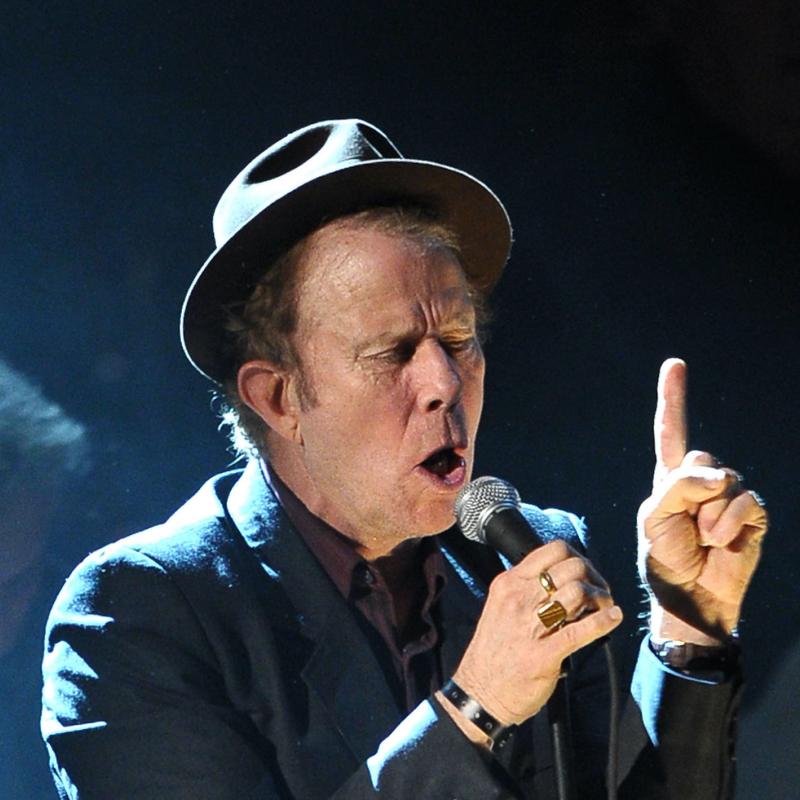

Singer and Songwriter Tom Waits

Since the 1973 release of his first album, âClosing Time,â Waits has won over fans with his original songwriting and distinctive, gravelly vocal style. One reviewer calls Waits âthe Ultimate hobo boho, a Jack-in-the-box cum storyteller.â Musicians including Johnny Cash, Bruce Springsteen, and Rod Stewart have recorded covers of his songs. He has also acted in films, including Sylvester Stalloneâs âParadise Alley,â Jim Jarmuschâs âDown By Law,â and Robert Altmanâs âShort Cuts.â Waits has two recent CDs; âAliceâ and âBlood Money,â a pair of very different sounding albums, were written and produced by Tom Waits and his wife and long-time collaborator, Kathleen Brennan.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on January 1, 2003

Transcript

DATE January 1, 2003 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Barry Manilow discusses his music

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Happy new year.

Today we conclude our encore week featuring our favorite music interviews

from

2002. First we hear from one of the most successful pop performers of the

'70s and early '80s, Barry Manilow. He had 25 Top 40 hits between 1974 and

'83, including "Mandy," "I Write The Songs," "Tryin' To Get The Feeling

Again," "Looks Like We Made It," "Daybreak," "Can't Smile Without You,"

"Copacabana" and "I Made It Through The Rain." Before he started writing

and

singing pop songs, he wrote commercial jingles and he was Bette Midler's

first

music director. He stopped recording his own songs in the '80s; there

didn't

seem to be much interest in them anymore. But recently he moved back on to

the pop charts with his `best of' compilation "Ultimate Manilow." And in

2002

he had a new CD of original songs called "Here At The Mayflower." I spoke

with him last March.

When I picked up your "Ultimate Manilow" record, the great hits record, I

looked at the songs on the back and I thought, `Well, I know that. I know

that one. Don't know this one. Don't know this one,' but when I played it,

I

realized that I knew the ones that I didn't think I knew. I just didn't

remember them by title.

Mr. BARRY MANILOW: Oh, I have insinuated my little self into your brains

over

the last 20 years.

GROSS: But that's the thing. I mean, you know, your songs were everywhere.

I mean...

Mr. MANILOW: They were everywhere.

GROSS: ...they were on the radio. They were on TV. They were in stores...

Mr. MANILOW: They were.

GROSS: ...and probably in elevators. I mean, they were just all over.

Mr. MANILOW: Oh, I'm sure they were in elevators. I'm sure they were in

elevators, yes.

GROSS: Well...

Mr. MANILOW: No, it's true. And, you know, I hadn't even listened to these

records. You know, I sing them nightly, but, you know, they don't sound

exactly like the old records did. And I actually--somebody was playing it

and

I actually listened to it and they all sound pretty good. I mean, you know,

we get into it and it sounds pretty good even, you know, all these years

later.

GROSS: What are some of the most unusual places you've heard your songs?

Mr. MANILOW: That's a great question. Some of the most unusual

places--well, you know, I must say that, you know, I have heard it in

restaurants, but unusual places, I don't know. You know, in big stadiums

and,

of course, you know, in boutiques and, you know, the karaoke bars. That was

pretty awful. I must say that was really...

GROSS: Well, tell me a karaoke story.

Mr. MANILOW: There was some very bad singer trying to do "I Write The

Songs."

It was really--I had to leave.

GROSS: Well, what were you doing there in the first place? Why were you in

a

karaoke bar?

Mr. MANILOW: I didn't know it was a karaoke bar. It was a Mexican

restaurant, and suddenly somebody got up and sang. I hope they didn't know

that I was there.

GROSS: That's really funny. The funny thing about "I Write The Songs"--you

know, people associate that song with you 'cause you recorded it, but you

didn't write "I Write The Songs."

Mr. MANILOW: I did not. And I knew it was going to get me in trouble as

soon

as Clive showed--you know, my hit record "Experience" is all--I give the

credit to Clive Davis, who was the president of Arista while I was there.

And

when I went on to Arista Records, I really knew nothing about pop music at

all. My first single was "Could It Be Magic," you know, a song that I based

on a Chopin prelude and it came in at eight minutes long, so what did I know

about pop music. So, I mean, you're supposed to have a three-minute record.

But when Clive started to work with me, he actually taught me the ins and

outs

of how to have a hit record. And he would submit songs to me so that I

would

arrange and produce and sing these outside pieces of material even though I

considered myself a songwriter. And "I Write The Songs" was one of the ones

he gave me. And I knew I was going to get in trouble if I accepted this

because, first of all, I figured everybody was going to think that I was

screaming about how I write all the songs in the world. What does he think

he

is? Burt Bacharach, you know?

And then, you know, I didn't write "I Write The Songs," but Bruce Johnson of

The Beach Boys wrote it, and when I sang it, I knew what he was trying to

get

to. He's saying the spirit of music is really the creator of everything,

you

know, of all composers' work. And I believe that, too. I believe that when

I'm writing, I have nothing to do with it. I'm just taking dictation. I

loved that idea, but I didn't think anybody listening to "I Write The Songs"

would really understand that. And I was right. Most people actually

thought

that I was singing about myself. And it didn't seem to bother anybody,

either, but it's true. I didn't write "I Write The Songs."

GROSS: Why don't we hear a little bit of "I Write The Songs."

(Soundbite of "I Write The Songs")

Mr. MANILOW: (Singing) I write the songs that make the whole world sing. I

write the songs of love and special things. I write the songs that make the

young girls cry. I write the songs. I write the songs.

GROSS: That's Barry Manilow, and that's one of his hits that's included on

the new CD "Ultimate Manilow."

Now let's talk about your early musical life. Your first instrument was, I

think, accordion?

Mr. MANILOW: I'm sorry.

GROSS: What happened?

Mr. MANILOW: Yeah. I'm sorry that it was the accordion.

GROSS: Oh, you're sorry that it was the accordion. Oh.

Mr. MANILOW: I--yeah.

GROSS: Why do you have to apologize?

Mr. MANILOW: Yes, I'm guilty. I'm guilty that it was the accordion.

GROSS: Well, the accordion is, like, the hippest instrument now. I don't

have to tell you that, you know?

Mr. MANILOW: Not when I played it.

GROSS: Not when you played it. The whole "Lady Of Spain" bit?

Mr. MANILOW: Yeah, I think every Jewish and Italian boy cannot get out of

Brooklyn, New York, unless he learns how to play the accordion. There's a

guard at the Brooklyn Bridge and you have to play "Lady Of Spain" before you

can go over the bridge. Everybody I knew played the accordion badly. I

happened to--you know, because I was more musical than the rest of my

friends,

I kind of got through "Hava Nagila" and "Lady Of Spain," and I actually

entertained my relatives. You know, they just thought it was the greatest

thing. It really wasn't the thing that turned my musical motor on, I can

tell

you, but you're right. There are people who play the accordion and actually

make it sound good. I was not one of those people.

GROSS: Did you sing when you played?

Mr. MANILOW: No, I never sang. I didn't sing until I started making

records.

I never really thought of myself as a singer. Singing was for other people

to

do.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MANILOW: Performing was for other people to do. I was at--if I was

going

to have a career in music at all, it was going to be as a musician. And

that

was it. No, I never sang.

GROSS: When you first started working professionally, I think it was in

more

of a supporting role, working--like you had an act with a woman singer--I

think Jeannie was her name?

Mr. MANILOW: Yes.

GROSS: And so you did some arranging for her. You were the pianist. You

sang some duets with her. But it was kind of--it sounds from your book like

it was a kind of supporting role. Did you see yourself as being like a

supporting role type of character in music?

Mr. MANILOW: Well, if I saw myself at all in music--and like I said, it was

so risky I never even dreamed about even that. But if I were to imagine

myself in the music business at that time, it would have been in a

supporting

role, as an arranger, as a pianist, as a producer, as a songwriter. Those

were my goals. Those were my dreams. Those were my fantasies that one day,

if I ever took the risk, that's where I would wind up. And so my first

professional engagement was as an accompanist for many, many singers, and

Jeannie was one of them.

GROSS: Well, your most famous position in a supporting role was as Bette

Midler's accompanist and music arranger, and this was in the era when she

was

playing at the Continental Baths, the gay steam bath in Manhattan. How did

you meet Bette Midler?

Mr. MANILOW: Well, she was one of the dozens of girl and boy singers that I

was accompanying. I had left CBS and I had begun accompanying singers, and

I

was making a really healthy living. Because I'm really a good accompanist.

I'm not that great a pianist, but I'm a really good accompanist. And they

are

always in demand in New York for auditions and people who need arranging and

coaching and stuff. So before I knew it, I was coaching just about every

singer that needed a pianist. I was booked like 12 hours a day. And Bette

must have heard of me and called me and asked if I would play a couple of

weekends for her at this placed called the Continental Baths. So I worked

for

a couple of weekends for her. I subbed for her piano player that she had,

and

she exploded and asked me if I would stay along with her. And I, frankly,

didn't want to just work for one person, and she couldn't afford to, you

know,

really just, you know, pay me for, you know, 24 hours a day, but Bette

Midler

was so incredibly talented that I just could not say `no,' and I began to

work

for her exclusively.

GROSS: Could you talk a little bit about what it was like to play to an

audience in a gay steam bath?

Mr. MANILOW: Well, I only worked there for two weekends. You know, people

got--you know, there's this unbelievable reputation that both Bette and I

had,

you know, about working in, you know, all the gay bath houses around the

world, you know, in Iran and Paris. But I don't know how long she worked

there, but I know for me, it was only two weekends, and it was a nightclub

situation there, although they were in towels, but it was a nightclub

situation, and there was a stage and lights and a sound system. And Bette

would come out and do her brilliant hour and a half, and they would freak

out,

and after the two weekends, she got booked at a place called the Upstairs at

the Downstairs, which was in Manhattan, and that was it. That was the end

of

my experience at the Continental Baths. But a lot of other people worked at

the baths because, like I said, it was a really interesting nightclub

situation, and the audiences were fantastic to the performers.

GROSS: My guest is Barry Manilow. We'll talk more after a break. This is

FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is Barry Manilow. He was one of the biggest pop hit makers

of the '70s and early '80s. Here's his first big hit, "Mandy."

(Soundbite of "Mandy")

Mr. MANILOW: (Singing) I remember all my life raining down as cold as ice,

shadows of a man, a face through a window, crying in the night, the night

goes

into morning. Just another day, happy people pass my way. Looking in their

eyes, I see a memory. I never realized how happy you made me. Oh, Mandy.

Well, you came and you gave without taking. But I sent you away. Oh,

Mandy.

Well, you kissed me and stopped me from shaking, and I need you today. Oh,

Mandy.

GROSS: At what point did you think, `Well, I'm going to be the one by the

microphone. I'm going to be the one singing. I'm going to have my own

act'?

What led you to that point?

Mr. MANILOW: You know, I was--it felt to me--it still seems to me that I

was

not in charge of that until way, way into my career. It felt like I was

just

catching up. Because when this opportunity to sing for myself came up, I

was

very reluctant to pursue this. I, first of all, didn't believe that I had

any

right to be a singer. I didn't think that I had a voice. I didn't think

that

I had a style. I didn't think that--and frankly, it wasn't anything that

I'd

ever aspired to anyway. I was still trying to come from that old Tin Pan

Alley school where you wrote songs for other people to record. But I got

this

record offer--a contract offer because somebody had heard my demos that I

had

sung. I had sung my own songs. And I was trying to get other people to

record them but I couldn't afford other singers, so I sang them myself. And

I

got an offer to make a record because Bell Records thought that I--I don't

know what they thought. They like what they heard. And I was, you know, so

interested in promoting my own songs that if that was the only way to do it,

I

took it.

But they said that I could not--they wouldn't give me this deal unless I

promised to go out and put a show together and promote it. Well, that--I

just

didn't know how to do that, but I was still conducting for Bette, and I

asked

her if I could sing a few songs to open her second act. And in that way I

would tour to promote my album and I would also stay music director for her

show. And she let me do it. So I would conduct her first act, then I would

open her second act with three of my songs from this new album that I had

made, and then I would continue to conduct. So that kind of worked out

great.

GROSS: Were you the first person to record one of your own songs?

Mr. MANILOW: Yeah, I was. Yes, I was. I was the first person to record

one

of my own songs, if you don't want to count "State Farm is there."

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Is that one of your commercials?

Mr. MANILOW: Yeah.

GROSS: Yeah, 'cause you wrote a lot of jingles before you made it as a

performer.

Mr. MANILOW: Yeah, I did. Yeah, I did.

GROSS: Oh, so how's the whole thing go? What's the first line in that, the

"State Farm is there"?

Mr. MANILOW: What? `Like a good neighbor, State Farm is there.'

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. MANILOW: Yeah.

GROSS: Oh, wow.

Mr. MANILOW: A very talented girl named Leslie Miller recorded that one

after

I wrote it, and then there was another one called "I am stuck on Band-Aids

and

a Band-Aid's stuck on me," and there was a whole batch of little kids that

recorded that. But, I mean, you know, I wouldn't consider that that was,

you

know, my first hit, you know.

GROSS: Well, let me back up to that. How did you start writing

commercials?

You know, we've got you going from Bette Midler's music director to

recording

demos and recording yourself. Where do the commercials fit it?

Mr. MANILOW: Well, when I was sending my demos out, a commercial agent

heard

some of these demos and they thought that I was writing commercially. And

they called me and said, `Do you want to up for a Dodge commercial?' And I

said, `Sure.' So I wrote a Dodge commercial, the melody to the lyric that

they gave me. And, of course, my commercial, not knowing anything, came in

like, you know, at four minutes or something. I was supposed to write it

for

30 seconds, you know. But they liked the melody, and ultimately after we

pared the whole thing down to 30 seconds, I got it. I got the first one I

went out for. And then they kept calling me to write various jingles. And

State Farm and Band-Aids are the ones that people still remember.

GROSS: Now what did you learn about the craft of songwriting from writing

commercial jingles?

Mr. MANILOW: Well, you know, I attended the New York College of Music and a

little while I went to Juilliard. And even though that was pretty good

training for my brains, the commercial world, my three years in the

commercial

world was really the college that I went to because I got to work with the

top

musicians. You know, they pay so well. You work with the top studio

musicians, who taught me really how to arrange music. You know, the oboe

player would say, `Psst. Come on over here. You see this thing? You're

writing it too high.' I'd say, `Really? I'm writing it too high?' `Yeah.

The oboe can't go up that high, so take it down an octave.' This would go

on

and on.

I worked with the great, great studio singers who taught me how to harmonize

and how to change the timbre of my voice. I worked with these great

engineers

who, you know, I would stand behind and I would see how they made these

jingles sound so hot that they would jump out of the radio. And as far as

the

songwriting goes, well, you're up against so many fantastic songwriters that

you've got to write the catchiest melody in 30 seconds. If you don't write

the best one, then the other guys get it. And so for three years, I was in

school, and I'll never forget that.

GROSS: Now did you ever come up with a hook for a jingle and think, `Wait a

minute. That's really a song. It's not a jingle. I'm keeping that one for

myself'?

Mr. MANILOW: A lot of them. But, you know, once you start to write

30-second

jingles, they really don't want to be much more than 30-second jingles.

GROSS: Uh-huh. So, like, there were ideas coming to you that you knew were

just, like, 30-second ideas?

Mr. MANILOW: Yeah. They were great hooks, but every time I tried to expand

them, they didn't work.

GROSS: Right. So there was no bridge to "You Deserve a Break Today"?

Mr. MANILOW: No, there's no bridge to "You Deserve"--and there's no bridge

to

"State Farm is there." And, you know, I mean, "State Farm is there" is a

pretty little melody, you know, that it could be a melody. But frankly,

it's

probably better as a commercial.

GROSS: When you were having all those top-10 hits--this was the '70s and

the

'80s--now all of us who remember then know that--well, most of us were

fashion

victims of one sort or another during that era, particularly in the '70s.

Mr. MANILOW: Weren't we?

GROSS: There were some pretty frightening things that we all wore, that we

all participated in. As a performer--I think it's even worse for

performers,

'cause performers have to wear more extreme versions of whatever...

Mr. MANILOW: And you're tortured with them for the rest of your life.

GROSS: Yeah. Here I am bringing it up again for you. So what are some of

your worst fashion memories?

Mr. MANILOW: Well, you know, I looked just like Rod Stewart and Elton John

did. You know, we were all wearing--we all looked like idiots back then,

you

know.

GROSS: With the white suits, yeah.

Mr. MANILOW: Yeah. With the glitter and the, you know, bell-bottoms and

the

Puca beads. Frankly I looked like Britney Spears back then with my long

blond

hair, really, before the boob job.

GROSS: Exactly. I was going to...

Mr. MANILOW: Right.

GROSS: I was going to mention that.

Mr. MANILOW: That was me.

GROSS: David Rakoff did an interview with you in the Sunday New York Times

Magazine.

Mr. MANILOW: Yeah.

GROSS: And you had mentioned that the Smithsonian had asked for your

"Copacabana" jacket, which you described...

Mr. MANILOW: Really. Isn't that funny?

GROSS: Yeah. You described it as being a `huge ruffled Desi Arnaz babaloo

kind of thing.'

Mr. MANILOW: It is. I did it as a joke in 1978. And, you know, they

take--and somebody took a photo of me. And, you know, from that moment on I

was sunk. I was just sunk. You know, I did it as a joke, but I think

people,

you know, thought that I was serious.

GROSS: Well, you said that the Smithsonian asked you for the jacket, you

sent

it to them and then they sent it back to you.

Mr. MANILOW: Well, here's--the real story is this. I just put my foot in

my

mouth. They asked me for the jacket. And, you know, it's such a funny

jacket, it's a joke. And so when I got it out--I was interviewed and the

interviewer said, `It's going to the Smithsonian.' I said, `Yeah. I always

knew it was going to wind up in an institution.' And the Smithsonian got so

insulted, they sent it back.

GROSS: Oh. Oh. So where is the jacket now?

Mr. MANILOW: Oh, it lives in my offices in Los Angeles, and it's still as

silly as it ever was, but now it has a little bit more meaning for me.

GROSS: Now I have a question for you, and I know you're asked this a lot,

but

has it bothered you that although you've had this huge success over the

years,

there's also been people, you know, listeners and some critics who, like,

use

the word `syrupy' to describe your music? And, you know, you've been the

butt

of jokes in some articles and other places. Is that difficult to handle?

Does it bug you?

Mr. MANILOW: Now and again it does. I'm, you know, human, so, yeah, it

does.

You know, I go into self-pity for a while and I pull the covers over my

head,

like any human being would do. But it never really stopped me, mostly

because

I believe in what I do. I listen to these songs, you know, trying to get

the

feeling, "This One's For You" and "When October Goes" and I say, `Well, I

like

them. I think they sound great.' And, you know, my band likes them, and

the

audiences like them. And so I just keep going. I just keep doing what I

love

doing and hope that there's an audience out there for it.

And I was always surprised at the critics when they felt they needed to be

so

mean-spirited in their opinions to somebody that they never even met. But I

forgave them, the little creeps, for making my life miserable for all those

years. But, you know, the best revenge is, like I said before, you know, I

continue to get the opportunity to make music, to make the music that I love

to make. And so that's really the best revenge.

GROSS: Our interview with Barry Manilow was recorded last March. His

greatest hits CD is called "Ultimate Manilow" and a CD of new original songs

is called "Here At The Mayflower."

I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of "Copacabana")

Mr. MANILOW: (Singing) Her name was Lola. She was a showgirl. With yellow

feathers in her hair and her dress cut down to there. She would meringue

and

do the cha-cha. And while she tried to be a star, Tony always tended bar

across the crowded floor. They worked from 8 till 4. They were young and

they had each other. Who could ask for more? At the Copa, Copacabana. The

hottest spot short of Havana. Here at the Copa, Copacabana. Music and

passion were always the fashion, at the Copa. They fell in love.

(Announcements)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Tom Waits discusses his musical influences, his career

and his two new CDs, "Blood Money" and "Alice"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

We're going to conclude our encore week series with one of the true

eccentrics

of pop music, Tom Waits. Earlier this year, in The New York Times, he was

described as `the poet of outcasts.' There's always been an element of

mystery

surrounding his life. The people he sings about are usually losers, hobos,

outlaws and drunks. The darkness of his lyrics is accentuated by the rumble

and rasp of his voice; a voice that sounded old even when he was young.

Waits

has been recording since 1973.

Tom Waits had two new CDs in 2002, "Alice" and "Blood Money." Each was

written for a music theater piece by Robert Wilson. Each has songs

co-written

with Waits' wife, Kathleen Brennan. When I spoke with Waits last May, we

started with a song from "Blood Money." This is "Misery Is The River Of The

World."

(Soundbite of "Misery Is The River Of The World")

Mr. TOM WAITS: (Singing) The higher that the monkey can climb the more he

shows his tail. Call no man happy till he dies. There's no milk at the

bottom of the pail. God builds a church, the devil builds a chapel like the

pistols that are growing on the trunk of a tree. All the good in the world

you can put inside a thimble and still have room for you and me.

If there's one thing you can say about mankind, there's nothing kind about

man. You can drive out nature with a pitchfork, but it always comes roaring

back again. Misery's the river of the world. Misery's the river of the

world. Misery's the river of the world. The higher that the monkey can

climb...

GROSS: Music from Tom Waits' new CD, "Blood Money."

Tom Waits, welcome to FRESH AIR.

Mr. WAITS: Oh, thanks. Thanks for having me.

GROSS: The arrangements for your songs are really good. Do you do the

arrangements yourself?

Mr. WAITS: Well, I collaborate with my wife on the songs in every aspect of

it, really; the composing and arranging and recording and all that business.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. WAITS: So, you know, we have a rhythm and a way of working. It's kind

of

like borrowing the same 10 bucks from somebody over and over again, you

know.

But, you know, when you live together, you know, it makes it a lot easier,

the

payback, you know.

GROSS: What was the music that you grew up listening to because your

parents

were listening to it? I mean, before you were old enough to choose music

yourself, what was the music in your house?

Mr. WAITS: Mm-hmm. Really young, mariachi music, I guess. My dad only

played a Mexican radio station. And then, you know, Frank Sinatra, and

later,

Harry Belafonte. And then, you know, I would go over to my friends' houses

and I would go into the den with their dads and find out what they were

listening to, because I was--I couldn't wait to be an old man. I was about

13, you know. I didn't really identify with the music of my own generation,

but I was very curious about the music of others. And I think I responded

to

the song forms themselves, you know; cakewalks and waltzes and barcaroles

and

parlor songs and all that stuff, I think--which is just really nothing more

than Jell-O molds for music, you know. But I seemed to like the old stuff;

Cole Porter and, you know, Oscars and Hammerstein and Gershwin and all that

stuff. I like melody.

GROSS: Now said your father listened mostly to the Mexican station and to

mariachi music.

Mr. WAITS: Yeah.

GROSS: Was your father Mexican?

Mr. WAITS: No. My dad's from Texas. He grew up in a place called Sulphur

Springs, Texas. And my mom's from Oregon. She listened to church music,

you

know, all that--Brother Springer, all the--she used to send money in to all

the preachers, you know. But the earlier songs I remember was "Abilene."

When I heard "Abilene" on the radio, it really moved me. And then I heard,

you know, `Abilene, Abilene, prettiest town I've ever seen. Women there

don't

treat you mean in Abilene,' I just thought that was the greatest lyric, you

know. `Women there don't treat you mean.'

And then, you know "Detroit City"--`Last night I went to sleep in Detroit

City, and I dreamed about the cotton fields back home.' I like songs with

the

names of towns in them, and I think I liked songs with weather in them, and

something to eat. So I feel like there's a certain anatomical aspect to a

song that I respond to. I think, `Oh, yeah. I can go into that world.

There's something to eat, there's a name of a street, there's a--OK. Yeah,

there's a saloon, OK.' So I think probably that's why I put things like

that

in my songs.

GROSS: When you started listening to older music and relating to that, did

other things accompany that, like a certain way of dressing or speaking or

behaving?

Mr. WAITS: Hmm. Oh, yeah, sure. You know, I wore an old hat and I drove

an

old car. I bought a car for 50 bucks from Fred Moody next door who's from

Tennessee, a '55 Buick Special, and, you know, AM radio in it. I guess.

Yeah, sure. I walked with a cane. You know, I was going overboard,

perhaps,

but...

GROSS: What kind of cane was it?

Mr. WAITS: You know, a cane, like...

GROSS: No, I mean, did it have like a silver tip? I mean, how...

Mr. WAITS: No, no, an old man's cane from a Salvation Army.

GROSS: Uh-huh.

Mr. WAITS: Yeah. And I carved my name in it and everything, you know.

GROSS: And what did you think that, that added to your image?

Mr. WAITS: It gave me a walk, I guess.

GROSS: Uh-huh. Uh-huh.

Mr. WAITS: It gave me something distinctive. `Oh, who was that guy in here

earlier with a cane? Did you see that guy?' It just gave me something that

I

liked identitywise, I guess.

GROSS: My guest is singer, songwriter and musician Tom Waits. His latest

CDs

are "Alice" and "Blood Money." We'll talk more after a break. This is

FRESH

AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is Tom Waits. His latest CDs are "Alice" and "Blood

Money."

Here's a song from "Blood Money" called "A Good Man's Hard To Find."

(Soundbite of "A Good Man's Hard To Find")

Mr. WAITS: (Singing) Well, I always play Russian roulette in my head, 17

black or 29 red. How far from the gutter, how far from the view, I will

always remember to forget about you. A good man is hard to find. Won't let

strangers sleep in my bed. And my favorite words are `goodbye,' and my

favorite color is red.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: That's "A Good Man's Hard To Find" from the new Tom Waits' CD "Blood

Money." He also has another new CD called "Alice," and we'll hear some of

that a little bit later.

Now I want to ask you about your voice. You have a very raspy singing

voice.

Was that a sound that you strove for, you know, that you worked on having,

or

is it what naturally developed?

Mr. WAITS: It's that old man thing. I couldn't wait to be an old man; old

man with a deep voice. No. I screamed into a pillow...

GROSS: Well, you know, John Mahoney, the actor?

Mr. WAITS: Sure, yeah.

GROSS: He told me he actually did stuff like that, that...

Mr. WAITS: Oh, yeah.

GROSS: ...he wanted a distinctive voice, and so he used to do these

exercises

that he practiced in a closet of just, like, shouting and trying to, you

know,

like growl a lot...

Mr. WAITS: Yeah.

GROSS: ...and it actually permanently did something to his vocal cords as a

result of it.

Mr. WAITS: Yeah, hooray. I'm all for it.

GROSS: Was, say, Louis Armstrong an influence on you?

Mr. WAITS: Oh, yeah, yeah, sure, yeah. You know, you can't ignore the

influence of someone like Louis Armstrong. You know, he's like a river.

He's

like a country to be explored in and of himself. And--but, yeah, he came

out

of the ground just like a potato. You know, he's completely natural. And,

yeah, sure, I love those tunes. And--but this one, this "A Good Man's Hard

To

Find," was, you know, an attempt to kind of tip my hat somewhat to that...

GROSS: Right.

Mr. WAITS: ...you know.

GROSS: Well, you actually sing in different kinds of voices on your new

CDs.

I mean, you have...

Mr. WAITS: Yeah.

GROSS: ...like, your very deep growly voice and then a lighter voice that

you

use.

Mr. WAITS: You know--well, it's just like--it's just a musical vocabulary,

really.

GROSS: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Mr. WAITS: You know, you find the appropriate sound for the correct tune

and

match them up. Yeah. You know, I like to scream and, you know, I can

croon,

you know, all that stuff.

GROSS: Have you ever worried about hurting your voice by...

Mr. WAITS: Oh, I've hurt it. Yeah, I have hurt it. But I have a voice

doctor in New York who used to treat Frank Sinatra and various people. He

said, `Oh, you're doing fine. Don't worry about it.'

GROSS: Oh, that's good.

Now you once said that you wish you could have been a part of the Brill

Building era, in which people like Carole King and Leiber and Stoller and

Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry were writing songs for singers and for vocal

groups. What do you think you would have liked about that?

Mr. WAITS: Well, I guess writing at gunpoint. It sounds really exciting to

me, those kinds of deadlines. I went into the rehearsal building on Times

Square in New York one afternoon and a really tiny little room. In fact, it

was probably smaller than the room I'm in right now, which is a little

larger

than a phone booth. There's just enough room for a little spinet piano and

then you could just barely close the door and there you were. And you could

hear every kind of music coming to you through the walls and through the

windows, underneath the door. And you heard African bands and you heard,

like, you know, comedians and you'd hear applause every now and then and

you'd

hear tap dancers. And I think I'd just like the whole melange of it, you

know. I mean, it all kind of mixes together.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. WAITS: I like turning on two radios at the same time and listen to

them.

I like hearing things incorrectly. I think that's how I get a lot of ideas

is

by mishearing something.

GROSS: Although you weren't part of the Brill Building thing...

Mr. WAITS: No.

GROSS: ...other people have recorded your songs, and I thought I'd play one

of them. Johnny Cash...

Mr. WAITS: Go right ahead, yeah.

GROSS: ...recorded your song "Down There By The Train."

Mr. WAITS: Yeah, right. That killed me. That was wild. I was like--I

said, `That's it. I'm all done now. Boy, you know, Johnny Cash did a song

of

mine. Boy, I'm all done. Thanks very much.'

GROSS: Do you...

Mr. WAITS: That was really flattering, and I loved the way he did it, too.

GROSS: Oh, yeah. Do you know how he knew the song or why he decided to

record it?

Mr. WAITS: Well, a lot of people sent him tunes 'cause he was doing this

record with Rick Rubin and different people that--or, you know, different

songwriters sent him tunes, and he just picked from them. So when someone

does a tune, well, especially someone that you've been listening to since

you

were a kid, it's a bit of a validation. And...

GROSS: Oh, yeah.

Mr. WAITS: So yeah, it's meaningful, you know.

GROSS: Yeah, Johnny Cash is pretty validating when it comes to that. Yeah.

Mr. WAITS: I know. Sure, yeah.

GROSS: OK. Well, let's hear it. This is from Johnny Cash's "American

Recordings" album, and this is the Tom Waits song "Down There By The Train."

(Soundbite of "Down There By The Train")

Mr. JOHNNY CASH: (Singing) You can hear the whistle, you can hear the bell

from the halls of heaven to the gates of hell. And there's room for the

forsaken if you're there on time. You'll be washed of all your sins and all

of your crimes, if you're down there by the train, down there by the train,

down there by the train, down there by the train; down there where the train

goes slow.

GROSS: That's Johnny Cash doing the Tom Waits song "Down There By The

Train."

My guest is Tom Waits.

Did you hear anything different in that song when Johnny Cash recorded it,

different from how you heard it in your head when you wrote it?

Mr. WAITS: Well, he changed some stuff around. That's normal. I do the

same

thing when I do somebody else's tune. You really have to--you try it on,

and

if it's a little tight in here or doesn't quite close over this--you cut it

or, you know, you make it fit. You want to make it sound like yours.

GROSS: It's funny, 'cause that song--when he sings it, it sounds like it's

like an unusual spiritual.

Mr. WAITS: Oh, yeah.

GROSS: And usually you write about godlessness.

Mr. WAITS: Godlessness? Really? Oh...

GROSS: Wouldn't you say?

Mr. WAITS: Oh, I don't know about that.

GROSS: The absence of God?

Mr. WAITS: I don't know. Do you think so?

GROSS: Well, some of the songs.

Mr. WAITS: Yeah? Hmm.

GROSS: Well, one of them explicitly, like "God's Away On Business."

Mr. WAITS: Oh, oh, OK. Well, he's away. He's not gone; he's just away.

And, like, you have to understand, he was on business. So, you know, and a

guy like him has got to be busy, you know, looking after a lot of things,

so...

GROSS: So did you meet Johnny Cash?

Mr. WAITS: No, no. I have not met Johnny Cash. I would look forward to

that

day down the road, and I would love to meet him.

GROSS: Tom Waits, you have two new CDs. We heard part of "Blood Money."

You

have another new CD called "Alice," which, I believe like "Blood Money,"

also

has its origins as a Robert Wilson music theater piece.

Mr. WAITS: Right. Yeah. Yeah. I was down in Hamburg quite a while ago,

in

'93, something like that.

GROSS: And what is "Alice" about?

Mr. WAITS: It's a hypothetical situation, kind of imagining the obsession

that Lewis Carroll had for this young girl Alice and...

GROSS: Oh.

Mr. WAITS: ...you know, what it might have been like inside of his mind in

Victorian England and all that stuff--the beginning of photography, and his,

you know, young gal, and, you know, it's kind of like a, you know, fever

dream

or whatever, kind of virus of the mind.

GROSS: Well, why don't we hear the title track? This is called "Alice,"

and

if there's something you want to say to introduce it, that's great, and if

not, we'll just hear it.

Mr. WAITS: Yeah. This is "Alice." This is kind of like the opening tune,

and it's like a private moment, and it's like sitting in a chair by

yourself,

thinking about someone.

GROSS: OK. Here's "Alice," the title track from the new Tom Waits CD.

(Soundbite of "There's Only Alice")

Mr. WAITS: (Singing) It's dreamy weather whereon you waved your crooked

wand

along an icy pond with a frozen moon; a murder of silhouette crows I saw in

the tears on my face, and the skates on the pond--they spell `Alice.'

I disappear in your name, but you must wait for me. Somewhere across the

sea

there's a wreck of a ship. Your hair is like meadowgrass on the tide and

the

raindrops on my window and the ice in my drink. Baby, all I can think of is

Alice.

GROSS: My guest is singer, songwriter and musician Tom Waits. His latest

CDs

are "Alice" and "Blood Money." We'll be back after a break. This is FRESH

AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is singer, songwriter and musician Tom Waits. He has two

new

CDs, "Alice" and "Blood Money."

Now you dropped out of high school. Why did you drop out? Is there

something

that you wanted to do instead, or did you just hate going?

Mr. WAITS: Oh, I wanted to go into the world, you know? Enough of this.

Didn't like the ceiling in the rooms. I didn't like the holes in the

ceiling,

those little tiny holes and the cork board and the long stick used for

opening

the windows.

GROSS: Oh, God, yeah, we had one of those in my elementary school. Yeah.

Mr. WAITS: Oh, I just hated all that stuff. I was real sensitive to my

visual surroundings, and I just--you know, I just wanted to get out of

there.

GROSS: Did any adults try to stop you, either your parents or teachers?

Mr. WAITS: I had good teachers. I had some--my folks broke up when I was

about 11, and so I had teachers that I liked a lot, that I kind of looked up

to. But then they seemed like they couldn't wait to get out into the world

themselves and do some, you know, banging around and learning and growing.

And so I thought maybe they were encouraging me to leave.

GROSS: So did you succeed in kind of getting out into the world, so to

speak?

Mr. WAITS: Pretty much, yeah.

GROSS: What'd you do?

Mr. WAITS: Oh, I hitchhiked all over the place, and...

GROSS: Did you ever do the street-musician thing?

Mr. WAITS: I didn't, but when I see people do it, I say, `Oh, man, I should

have done that.' I'll tell you, you really get your chops together, you

know?

'Cause I'm real, I guess, particular about now, you know, those things. I

get

real nervous when--but I think I wish I had done that, because it looks like

it takes a lot of guts, and I think that you would probably cut through a

lot

of potential stage fright that you would eventually have, and maybe it'd

help

you down the road. I don't know.

GROSS: So has stage fright been an issue for you?

Mr. WAITS: Oh, yeah, yeah. I go through all kinds of stuff about it. But,

you know, when I get out there I'm all right. But my first gig--my first

big

gig--was an opening show for Frank Zappa, and I think that was difficult. I

was kind of like the rectal thermometer for the audience, and it was a

little

awkward for me. I was alone, and I was performing in front of large groups

of

people, and they were verbally abusive. And I think it--I'm like a dog. I

was so beat as a dog, so...

GROSS: Is there a point in your career that you see as a turning point from

getting to where you are now from where you were when you started

performing?

Mr. WAITS: Oh, yeah, probably--well, I got married, really, you know? That

was it, you know? I mean, that's, like, the most important thing I ever

did.

I mean, and Kathleen really was the one who encouraged me to produce my own

records, you know, and...

GROSS: What kind of music background is she from?

Mr. WAITS: Oh, she's got, like, opera in there, and she was going to be a

nun, you know, so we changed all that.

GROSS: Yeah, I guess so.

Mr. WAITS: But, you know, she's adventurous, you know? And she kind of

picks up a lot of stations that I don't pick up. I get kind of narrow and

concerned in making something--giving it four legs and getting it to stand

up,

and she's more interested in what goes inside. And she's very feminine, and

I

think that's what works. And the idea of going in the studio and doing your

own record is kind of scary. You know, pick the engineer, pick all the

musicians and, you know, write some kind of mission statement for yourself

and

what you want it to be and sound like and feel like, and take responsibility

for everything that goes on the tape. That's a lot to do, especially--it's

a

lot for a record company to let you do when you behave like I did, and they

didn't--they thought I was--you know, I think they thought I was a drunk,

and

they--you know, and I was really non-communicative and I scratched the back

of

my neck a lot and I looked down at my shoes a lot, and I, you know, wore old

suits and they were nervous about me. But once I got a taste for it. I

really like it.

GROSS: Tom Waits, thank you so much. It's really been great to talk with

you. Thank you.

Mr. WAITS: Oh, oh, we're all done.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. WAITS: Oh, OK. Nice to talk to you, Terry.

GROSS: Tom Waits, recorded in May, after the release of CDs "Alice" and

"Blood Money."

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

All of us at FRESH AIR wish you a happy and healthy new year.

We'll close with a song from Tom Waits' CD, "Blood Money." This is "Coney

Island Baby."

(Soundbite of "Coney Island Baby")

Mr. WAITS: (Singing) Every night she comes to take me out to dream land.

When I'm with her I'm the richest guy in the town. She's a rose. She's a

pearl. She's a spin on my world. All the stars, they've got wishes on her

eyes. She's my Coney Island baby. She's my Coney Island girl. She's a

princess in her own dress. She's the moon in the mist to me. She's my

Coney

Island baby. She's my Coney Island girl.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.