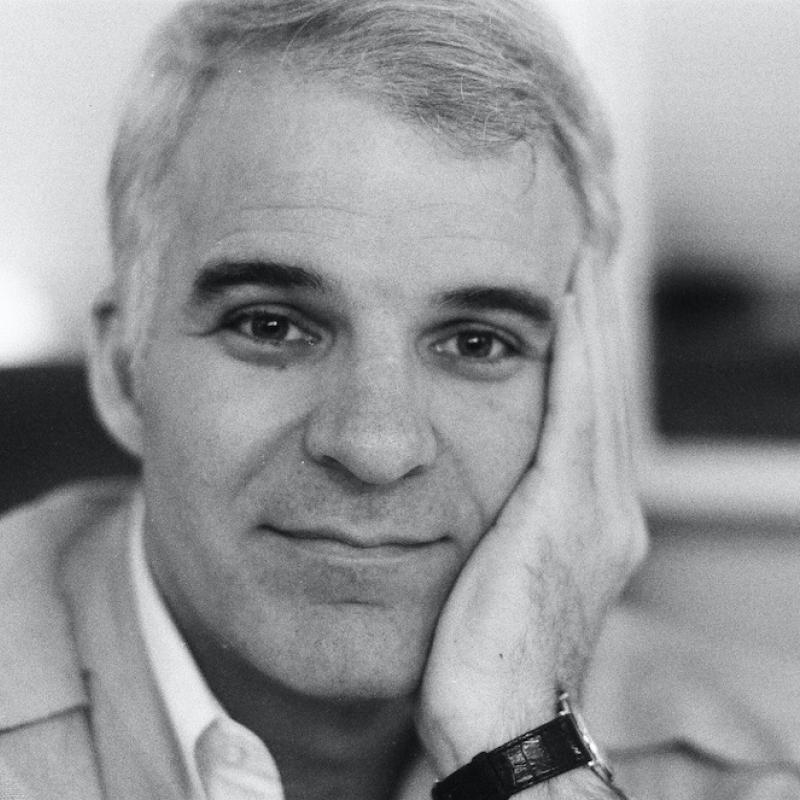

Actor and Comic Steve Martin

His novel The Pleasure of My Company follows his best-selling novella Shopgirl. He wrote the play Picasso at The Lapin Agile and is the author of a collection of short stories, Cruel Shoes. Martin's screenwriting credits include L.A. Story and Roxanne. He has also starred in such films as The Jerk; Planes, Trains and Automobiles; The Lonely Guy; Parenthood; Father of the Bride; Housesitter; Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid; All of Me; The Man with Two Brains; Sgt. Bilko; Leap of Faith and Little Shop of Horrors. He won a Grammy Award for his album Let's Get Small.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on October 6, 2003

Transcript

DATE October 6, 2003 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Steve Martin on his new book "The Pleasure of My

Company"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

My guest is the great actor and comic Steve Martin, the star of such films as

"The Jerk," "All of Me," "Roxanne," "Dirty Rotten Scoundrels," "Parenthood,"

"LA Story," "Father of the Bride," "The Spanish Prisoner," "Bowfinger" and

"Bringing Down the House." Steve Martin has also established himself as a

novelist. "Shopgirl," the novel he published three years ago, was a

best-seller. He's now adapting it into a film. He has a new novel called

"The Pleasure of My Company." And if you're thinking it's a wild-and-crazy-guy

kind of story it's not, but it is witty. It's about Daniel Pecan Cambridge, a

man who has so many neurotic fears and compulsions that he seldom dares to

leave his Santa Monica apartment. I asked Steve Martin to start with a short

reading from "The Pleasure of My Company."

Mr. STEVE MARTIN (Actor/Comedian/Writer): This all started because of a

clerical error. Without the clerical error, I wouldn't have been thinking

this way at all. I wouldn't have had time. I would have been too preoccupied

with my new friends I was planning to make at Mensa, the international society

of geniuses. I had taken their IQ test, but my score came back missing a

digit. Where was the 1 that should have been in front of the 90? I fell

short of the genius category by a full 50 points, barely enough to qualify me

to sharpen their pencils. Thus I was rejected from membership and facing a

hopeless pile of red tape to correct the mistake.

Santa Monica, California, where I live, is a perfect town for invalids,

homosexuals, show people and all other formally peripheral members of society.

Average is not the norm here. Here, if you're visiting from Omaha, you stick

out like a senorita's ass as the Puerto Rican Day Parade. That's why, when I

saw a contest at the Rite Aid drug store asking for a two-page essay on why I

am the most average American, I marveled that the promoters actually thought

they might find an average American at this nuthouse by the beach.

This cardboard stand carried an ad by its sponsor, Tepperton's(ph) Frozen

Apple Pies. I grabbed an entry form and, as I hurried home, began composing

the essay in my head. The challenge was not to present myself as average, but

how to make myself likable without lying. I think I'm appealing, but

likability in an essay is very different from likability in life. See, I tend

to grow on people, and 500 words is just not enough to get someone to like me.

I need several years and a ream or two of paper. I knew I had to flatter,

overdo and lay it on thick in order to speed up my likability time frame, so I

would not like the sniveling patriotic me who wrote my 500 words. I would

like a girl with dark roots peeking out through the peroxide who was laughing

so hard that Coca-Cola was coming out of her nose, and I guess you would, too.

But Miss Coca-Cola Nose wouldn't be writing this essay in her Coca-Cola

persona. She would straighten up, fix her hair, snap her panties out of her

ass and start typing.

`I am average, because,' I wrote, `I stand on the seashore here in Santa

Monica and let the Pacific Ocean touch my toes, and I know I am at the most

western edge of our nation and that I am a descendent of the settlers who came

to California as pioneers. And is not every American a pioneer? Does this

spirit not reside in each one of us in every city, in every heart, on every

rural road, in every traveler in every Winnebago, in every American living in

every mansion or slum? I am average,' I wrote, `because the cry of

individuality flows confidently through my blood with little attention drawn

to itself, like the still power of an apple pie sitting in an open window to

cool.'

I hope the Mensa people never see this essay, not because it reeks of my

manipulation of a poor company just trying to sell pies, but because during

the 24 hours it took me to write it, I believed so fervently in its every

word.

GROSS: Thank you. That's Steve Martin reading from his new novel, "The

Pleasure of My Company."

Well, your character, although he's writing this essay on why he's the most

average American, is very not average, wouldn't you say?

Mr. MARTIN: Very not. He's a young man in his early 30s. He's unclear in

the book about his real age, which he doesn't reveal until the last couple of

pages for a reason you'll find out later. And he's isolated. He's kind of a

benign neurotic. He has certain rituals. He can't cross the street at the

curb. He has to find two opposing scooped-out driveways. He has to keep the

wattage in his apartment constant at 1,125 watts. For example, if he turns

out a light in his bedroom, he must turn on a light in the living room or

kitchen, and it's only a three-room house. And this is a story of how his

life opens up, finally opens up as he describes himself, that he has narrowed

his life down to keep everything out. In fact, his stated goal was to have so

many rules and conditions that he could control everything that was coming

into him, and then he would slowly open the doors one at a time.

GROSS: Now your character wants to get into Mensa, and he thinks they made

some kind of clerical error in leaving off the number 1 before his 90. You

also wrote a piece for The New Yorker about Mensa.

Mr. MARTIN: Yes. As I say, there was precursors to this.

GROSS: Right, right.

Mr. MARTIN: And I think that I needed to start that way in order to kind of

go back to that essay, revisit that character in my head and kick it off from

where I left it off before.

GROSS: What does Mensa mean to you? I mean, it's this group of people with

high IQs who get together.

Mr. MARTIN: Right. I always saw it in this way. OK, well, you might have a

high IQ, but what have you done lately? And I think the real stroke of genius

is in what you do and not in some score. So I looked at it a little bit

cynically. I have no, you know, cynicism toward any Mensa member, but it was

just a way I looked at the world, that accomplishments are what matters and

not scores.

GROSS: Steve Martin is my guest, and he has a new novel called "The Pleasure

of My Company."

I'd be interested in hearing why you want your writing to be writing for the

page as opposed to writing for the screen.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, I started writing in 19--probably--60--What?--'5 when I

wrote little essays in college that later became a book I published called

"Cruel Shoes." And then I was writing for my comedy act throughout the '60s

and '70s. And then in the late '70s, I started writing screenplays,

co-writing them with, you know, other writers, "The Jerk" and "Dead Men Don't

Wear Plaid" and "The Man With Two Brains."

GROSS: Of course, right. Right.

Mr. MARTIN: And in the mid-'80s, I started writing solo screenplays;

"Roxanne" and "L.A. Story" and "Simple Twist of Fate." And then--I really

have written a lot of screenplays, "Bowfinger," too.

And then in the early '90s, I really got a call from The New York Times asking

me to write something on this--there was a discovery of a Michelangelo statue

here in New York City. So I wrote a little parody of that and went into The

New Yorker ultimately. Actually, the truth is, I really enjoy writing for the

page because it's an utterly different thing. You know, screenplay is

description and dialogue.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. MARTIN: And a book is really about sentences and paragraphs and their

structure and their rhythm and the use of words, the exact, precise use of

words. You know, a screenplay can be--you know, I remember one year, I, you

know, saw a little list in a magazine of the, you know, best lines from the

movies this year. And they were all, like, `Come on, let's get out of here.'

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: The catchphrases.

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah. Yeah. And, you know, it's just a very different--what

your best line in a movie is is very different from a best line in a book. So

it's a completely different enterprise.

GROSS: You know, as an actor, particularly early in your career, your persona

was usually very extraverted. As a writer, like, your two novels are about

really introverted characters, and I think that's an interesting contrast.

Mr. MARTIN: Right. Well, I think actually that without, you know, being too

boring, analyzing my sort of stage act, that character--sorry to talk about

that in that way, but he was a bit crazy. He was a little--I was, on stage,

very similar to this character. Really, it's like, on stage, I was really

just expressing a perverse thought on the way the world worked. And I

remember this one bit I did was that I was so mad at my mother--I used to

scream it, of course--because she wanted to borrow $10 for some food. And you

know, there's just some kind of link here between this character, who just

sees things in the odd, odd way.

GROSS: All writers talk about, you know, facing the blank page and so on, but

it really is true that the difference between being an actor and being on the

set and being--you know, working with other people is so different than

staying at home and writing.

Mr. MARTIN: Right. You bet.

GROSS: Do you like that? Do you like that more isolated process of writing?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, you know, they compliment each other so well, because, like

you say, movies are active and social and physical, and writing is solitary

and personal. And I never wanted to be an actor who sat home and waited for

scripts to come through the door. I mean, that would drive me insane, waiting

and hoping. And so I always wrote. I always did comedy, and I just like the

activity of it, you know. I just find that when I'm idle, which I always

enjoy, I always find that something comes up. Something pops up, so I'll get

out the computer and start typing. You know, having the working...

GROSS: Did you think you approached writing with a different personality than

the one you approach acting with?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, I would have to say yes, because, you know, it's just so

different. They are completely different. But I really think that my acting

has influenced my writing, because as an actor, you finally, as you get a

little better at it, you realize you're observing character. And you realize

that it's the details that make character. It's the little tiny actions. And

so in writing, I think I realize, or at least I like to pick up those details

that determine character.

GROSS: And those are the same kinds of things you have to pick up when you're

acting, too, aren't they? I mean, you're not describing them.

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah, absolutely. That's what I'm saying.

GROSS: You're doing them, yeah. Yeah.

Mr. MARTIN: Right. It's from acting, but the strange thing about acting is

it's also what you don't do. I mean, it's almost a thought process in your

head that is so expressive. So the more you can detail it in your mind, and

without, you know, what we call in acting indicating an emotion--I remember

once, the director, Herb Ross, he was mad at an actress. And I said, `What's

the matter?' He said, `Well, she supposed to be mad. She's supposed to be

mad.' And I said, `Well, she's yelling.' He says, `Yes, but anger has a

thousand faces,' and I always remembered that. It's, like, `Oh, yeah.' Some

of the angriest moments I've ever felt are when I did nothing or said nothing

and expressed nothing.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MARTIN: So there's always those choices in behavior.

GROSS: My guest is Steve Martin. More after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Steve Martin is my guest, and he's just published his second novel.

It's called "The Pleasure of My Company." And his first novel, "Shopgirl," is

being adapted into a film.

You know, I think it's hard when you're so accomplished at something to try

something that you're new to, as you were new to writing novels.

Mr. MARTIN: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. Yes.

GROSS: And, you know, when you're at the top of your profession in one thing

and then you're brand-new to something else, you can fail. You can be flawed,

and you can be very insecure. You have no track record. So did starting to

write bring out insecurities that you weren't used to? Because...

Mr. MARTIN: Oh, yes, absolutely. But there's a trick when you first start

writing, is that...

GROSS: Teach it to me, please.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, you don't have to show it to anybody.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MARTIN: When you're sitting there alone, and you haven't, you know, made

a deal with somebody to deliver a book, you're really on your own. And it's

like putting your toe in the water. You can have written something, and you

give it to a friend, or you ask someone's opinion. So you always fool

yourself, because--you know, the reason I say you fool yourself, ultimately,

you do want it to be out there, but you fool yourself by saying, `It doesn't

matter. It can be lousy. No one will ever see it if it's lousy.' And, of

course, they do see it, and sometimes it's lousy.

GROSS: So you would agree that self-delusion is an important part of

writing.

Mr. MARTIN: Very, very important. I really do. I think it is. Like, I

remember the first night I previewed my play, "Picasso at the Lapin Agile," I

had never written a play. I had written screenplays. But I was in Melbourne,

Australia, and now it's 10 minutes before curtain, and all I could think is,

`What have I done?' I didn't know if there was going to be a laugh, you know,

anything. It could have been so humiliating. But then only, you know, 40

people would have seen it, and I could have gone home with my tail between my

legs. But I just want to add that I really don't have a tail. It's just a

figure of speech.

GROSS: Do you write many drafts before publishing?

Mr. MARTIN: What I do is I write without inhibiting myself, and then I

will--draft is not quite the right word in my head. I go through, and I start

editing. I start reading it, and I start reading it over and over and over,

which can get very tiresome, so sometimes, I'll put it down for three months,

come back, read it again. Then I'll read it aloud to myself. And then I'll

read it to my dog. And I find that reading it makes you catch every word.

And to me, every word is important, because I'm a reader who gets bored

quickly, so I need to have these sentences on the move and be interesting all

the time. So I try to catch everything.

GROSS: Is your dog helpful when you're reading to him?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, he's my audience. I'm not looking for his response.

GROSS: You just need somebody to read to?

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah.

GROSS: Did you feel an obligation to be funny when you started writing,

'cause that's what people expect of you?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, no, because the first book, "Shopgirl," although it has

funny moments, I wouldn't call it a funny book.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MARTIN: But in "Pleasure of My Company," I actually wanted the book to be

funny, and I knew that I had a character who could be funny. And, you know,

whenever you start, whenever I start even a New Yorker essay, I have the idea,

I think, `OK, what is the potential of this?' I have no idea what the

individual bits will be or moments or anything, but does it seem rich or does

it seem I'm going to run out of steam in a couple of paragraphs? And I felt

with this character, he could really keep going. And it's a cliche to talk

about the discovery of character as you keep writing, but I found that my mind

retains little details of things I've written 40 or 50 pages ago. And so

something that you wrote that was very, very casual, a little aside, a little

something he did comes back at a certain moment, and it becomes big, because

now this tiny little thing impacts something else. And it's like weaving a

web or weaving something else, a caftan, I don't know which I'm weaving. But

that's what I really like, is where the details start to add up.

GROSS: Well, you know, you've had your success in the book world and the film

world, and you've been on the best-seller lists, and you're probably the only

person to have hosted both the Academy Awards and the National Book Awards?

Mr. MARTIN: I guess I am.

GROSS: Yeah, I think so.

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah. I'll have to stop any Oscar hosts from hosting the

National Book Awards, so I can keep my uniqueness.

GROSS: So, I mean, I think that would probably give you a good seat as to

some of the differences between the two worlds, the film world and the book

world?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, the differences--you know, the book world is much, much

slower than the film world. I mean, the film world is so oriented to

promotion and getting the word out in certain ways, getting the word out in

very vibrant ways and very specific soundbite ways. And, for example, I mean,

here I am talking to you for 40 minutes about my book. This would never

happen about a film, I mean, in terms of the way a film is generally promoted.

But it's the way books are promoted. They're talked about in depth, in much

slower, slower ways.

GROSS: Well, and the numbers are so much smaller, too, aren't they?

Mr. MARTIN: Right, right.

GROSS: Like a best-selling book probably doesn't come close to the ticket

sales of a mediocre-selling movie.

Mr. MARTIN: Probably, yeah. But you know what I found is that when I started

writing for The New Yorker, I noticed I got more reaction from one essay--and

I'm talking about actual reaction that I could feel--I mean, people saying

things--than I did for movies. Like entire movies that cost millions and

millions of dollars to come out, and I would hear, you know, very little, or

somebody would say, `Nice movie,' or something. But these essays, they

started to--I guess because they're so intimate with the reader, they're so

intimately involved, that it stays with them longer. You know, a movie,

sometimes I walk out, I've forgotten it, you know, as I'm exiting the lobby.

GROSS: Steve Martin. His new novel is called "The Pleasure of My Company."

Here's a scene from the film "Bowfinger," which he wrote and directed. Martin

plays a would-be director who has a movie script he believes is finally his

ticket to success, so when Kit Ramsey, the big star he needs for the film,

refuses to even read it, Martin lies to his cast and crew, telling them Ramsey

is on board. Here he is explaining his plan to his cameraman, played by Jamie

Kennedy.

(Soundbite from "Bowfinger")

Mr. JAMIE KENNEDY: You told them we're gonna make this movie?

Mr. MARTIN: That's right, I did. That's what I did.

Mr. KENNEDY: So you're gonna have to tell them.

Mr. MARTIN: Tell them what?

Mr. KENNEDY: That we're not gonna make the movie.

Mr. MARTIN: What do you mean, we're not making the movie? Dave, I made them

a promise.

Mr. KENNEDY: But how are you gonna make the movie with Kit Ramsey? He said

no.

Mr. MARTIN: You don't think I thought about that? You don't think I worked

that out? We're making this movie with Kit Ramsey, except...

Mr. KENNEDY: Except what?

Mr. MARTIN: Except he won't know he's in it.

Mr. KENNEDY: What?

Mr. MARTIN: We secretly follow him around with a camera. We have our actors

walk up to him and say their lines, and he's in our movie, and we don't have

to pay him.

Mr. KENNEDY: Well, what's he gonna say?

Mr. MARTIN: What difference does it make what he says? It's an action movie.

All he's gotta do is run. He runs away from the aliens, he runs toward the

aliens. He runs away from the aliens, he ru--come here, I want to show you

something. Got this all worked out, I think. There are six major scenes with

Kit. Those are the ones in red. He's not in any of the other scenes, so we

just shoot those with our own actors on our own time and bingo, we've got a

movie.

GROSS: Steve Martin in "Bowfinger." He'll be back in the second half of the

show. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: Coming up, we continue our conversation with Steve Martin. And on the

eve of the California recall, linguist Geoff Nunberg considers an item on the

ballot that nobody seems to be talking about.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross, back with comic actor, director

and writer Steve Martin. His many films include "The Jerk," "All of Me,"

"Dirty Rotten Scoundrels," "Parenthood," "Father of the Bride," "The Spanish

Prisoner," "Bowfinger" and "Bringing Down the House." He's also the author of

the best-selling novel "Shopgirl." Now he has a new novel called "The Pleasure

of My Company."

Well, I'd like to mention an essay of yours that I particularly liked, and it

was a personal essay about your late father.

Mr. MARTIN: Yes.

GROSS: And, you know, it was about how he had wanted to act and had done some

amateur acting when he was young, and how you had, you know, kind of rocky

relationship. And one of the things you talk about is how you decided to take

your parents out to lunches every Sunday so that you could get to know them

better, and you realized that they were bickering all the time when you took

them out to lunch, so you really weren't getting anywheres.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, yeah, they were contra--right.

GROSS: And then you...

Mr. MARTIN: They were contradicting each other, so I decided with them to

take them out alone each, you know, one at a time.

GROSS: And that worked.

Mr. MARTIN: And without the other person there, I could get stories and, you

know, anecdotes and opinions and attitudes that I never would have gotten if

they'd been there together.

GROSS: I thought that was so smart to think of that. And then you also wrote

about how your father, when he was basically on his deathbed, said to you,

`You did everything I wanted to do.'

Mr. MARTIN: Right.

GROSS: I thought, wow, that's--what a zinger for...

Mr. MARTIN: Well, it's quite a moment, really.

GROSS: Yeah. Did you ask yourself whether he would think it was OK to say

that, you know, to write that? I guess one of the questions I'm asking is, do

you think the standard does or should change when someone that's no longer

with us--about what's too private to say about them? You know what I mean?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, I did not feel that that was too personal. I was very

particular about what I said. In fact, I ran the essay by my sister to get

her opinions on anything that might be too personal. But I didn't feel that

it was too personal because he was really demonstrating kindness there at that

moment.

GROSS: Because he'd been so critical comparatively in the past of you.

Mr. MARTIN: Right, mm-hmm, yeah.

GROSS: Right. You haven't written a lot of personal stuff. Most of your

stuff is--most of your writing is fiction or humor. And there's something

that you wrote in an essay in The New York Times that really meant a lot to

me. I mean, I wrote it down and stuck it in my computer so I could refer to

it. I've mentioned it in a talk. And this was in the context of talking

about why you decided to have a show of art from your art collection,

something you used to be very private about. And you said, `Being a celebrity

can cause an accidental cheapening of the things one holds dear. A slip of

the tongue in an interview and it's easy for me to feel I've sold out some

private part of my life in exchange for publicity.' I really thought that was

so well-put, and I'm in the position, you know, of asking the questions

usually. And I know that that's always a possibility--Do you know what I

mean?...

Mr. MARTIN: Well...

GROSS: ...that both the interviewer and the interviewee risk cheapening

things. And at the same time, I mean, I don't want that to happen; that's,

like, the unintentional occasional result. But, you know, I think you try on

both ends to be really sensitive to that, but I thought you just put it so

well.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, I think--you know, the problem with, you know, being

interviewed as a celebrity is that, for example, you and I are talking now,

we're talking on NPR, and it's a very special circumstance; it's much more

detailed. It can be way more personal than, say, I would be on "Entertainment

Tonight." But--and so I'm willing, much more willing to talk about private

things in this circumstance. But what happens is this I might pay for three

years from now in an interview with "Entertainment Tonight" because they will

bring up maybe something I've said that's personal. Now actually that's kind

of diminished because, you know, I'm at a nice stage in my career where, you

know, I can get around and there's no sort of, you know, crazy invasion of

privacy or--and I also learned to keep relationships to myself because I've

realized that that kind of--I mean, I realized this a long time ago--that kind

of focus on your personal life actually damages it.

GROSS: You know, at the same time, I'm sure when you're doing an interview,

even if you just see it as a promotional interview, you want to be as

interesting as possible. So then again there's the kind of trade-off between,

well, this'll make it more interesting; on the other hand, it's personal, I'd

just as soon not talk about it. So does that equation play out in your mind?

Mr. MARTIN: No, it doesn't, it doesn't, because there's almost no way for me

to make an interview about a movie interesting. I've realized that. You

know, I've listened to Howard Stern, and he always plays celebrities'

interviews, and we all just sound ridiculous, you know. You know, and I know

that as I'm giving these interviews, I am that person that will be mocked

because there's just--you know, it's just not ultimately that interesting, you

know. So you have to kind of make up things. And you know, it's just a funny

business. It's like the worst day of your life, you know, when you have to go

talk about the movie you've made, especially if it's a...

GROSS: You're making me feel terrible.

Mr. MARTIN: Pardon me?

GROSS: You're making me feel terrible, 'cause...

Mr. MARTIN: No, no, it's not you. I'm talking about the soundbite industry.

GROSS: Do you get obsessive about things where you really--once you get into

it, you're into it?

Mr. MARTIN: Yes. But I think that's--there's other terms for that.

GROSS: Devoted.

Mr. MARTIN: Well--yeah, well, I remember an article in The New York Times

years ago called In the Zone(ph), and it talked about, for example, when a

basketball player is hot and he's just sinking these, you know, baskets one

after another. And they talk about people who are in the zone losing

consciousness of time. And that--or if you're--I mean, we've probably all

been stuck with a computer problem, and you've looked and suddenly four hours

have gone by while you're trying to solve it. And that to me is what writing

is. It just is so absorbing that time goes by; time goes by quickly, or it

stops.

GROSS: Yeah, but the problem is with writing, if time goes by quickly and you

don't like what you've written in that time, you feel like you've lost

something. Maybe that doesn't happen to you.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, you know, I don't write unless I'm ready. So usually I

find if you're in the zone, you usually like what you've written. And if I'm

not in the zone, I generally don't write.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MARTIN: I will edit at that point using what we call the monkey mind.

GROSS: What do you mean?

Mr. MARTIN: Somebody gave that to me years ago. It was like the monkey mind

was the--you know, there was your creative mind and then there was your monkey

mind, and your monkey mind was really consciousness. You know, and the monkey

mind should do the editing; it's the one that's not original; it's the one

that's imitative. And that's just a term for doing the slave work of writing,

when you're organizing...

GROSS: Boy, the editor community is going to be very angry at that

description.

Mr. MARTIN: No, no. No, I rely heavily on editors. I really need response.

GROSS: My guest is actor, comic and writer Steve Martin. His new novel is

called "The Pleasure of My Company." More after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Steve Martin is my guest. His new novel is called "The Pleasure of My

Company." Martin has starred in many films, including the 1998 David Mamet

movie "The Spanish Prisoner." Here's a scene from it. Martin plays Jimmy

Dell, an apparently charming and wealthy man who befriends Joe Ross, played by

Campbell Scott. Here Jimmy is giving Joe business advice.

(Soundbite of "The Spanish Prisoner")

Mr. MARTIN: (As Jimmy Dell) You know what the man said about verbal

agreements; they're not worth the paper they're printed on.

Mr. CAMPBELL SCOTT (As Joe Ross): That's what my boss just said to me.

Mr. MARTIN: (As Dell) In re what? I mean, what, what is he talking about?

Mr. SCOTT: (As Ross) Well, I've got a--oh, thank you.

Mr. MARTIN: (As Dell) You're welcome.

Mr. SCOTT: (As Ross) I did something for the company, and they owe me

something. I think I need to get it in writing.

Mr. MARTIN: (As Dell) I would. What do they owe you?

Mr. SCOTT: (As Ross) I think they owe me a lot of money.

Mr. MARTIN: (As Dell) What do you mean, you think?

Mr. SCOTT: (As Ross) I invented something for them. It's a work for hire;

they own it. But it's...

(Soundbite of phone being dialed)

Mr. MARTIN: (As Dell; on phone) Hello, is Mrs. DeSilva(ph) in? (To Ross) Who

told you it was a work for hire?

Mr. SCOTT: (As Ross) Well, they did.

Mr. MARTIN: (As Dell) You invented it?

Mr. SCOTT: (As Ross) Well, I...

Mr. MARTIN: (As Dell) I'm not a lawyer; I'm just a guy. Tell me, you

invented it?

Mr. SCOTT: (As Ross) Yes.

Mr. MARTIN: (As Dell) Uh-huh.

GROSS: "Spanish Prisoner" was written and directed by David Mamet.

Mr. MARTIN: Yes, absolutely.

GROSS: Oh, it must have been a pleasure to read his dialogue.

Mr. MARTIN: Fabulous. I loved doing it. You know, his dialogue is a

challenge for an actor because it's incredibly precise, including the `ers'

and `uhs' and they way we speak going back o--retracing our words, just like I

just did, or like I just did. And so it's really fun to do that, 'cause you

really have to--you cannot, as you're speaking the dialogue, you can't get

ahead of yourself. You have to actually forget at that moment what you're

going to say next.

GROSS: What do you mean, that you have to forget it?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, in other words, if it's written that there's a hesitation

or an `er' and an `uh,' if you come up to it and you're prepared for it, it's

going to sound like (speaking deliberately) `er, uh.' It's going to be very

dead. So you have to talk as though you know what you're going to say but you

don't. You have to forget what you're going to say at that moment.

GROSS: And then you have to remember it again.

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah, well, it's acting. You know what it is.

GROSS: That's right.

Mr. MARTIN: You know...

GROSS: So do you feel like you learned any new things from working with

Mamet?

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah, but it's--you know, he was a really good director for me

because he kept reminding me--you know, my character was supposed to be very

wealthy and very confident, and he kept reminding me of what that is, which is

nothing gets to you; no one can get to you. And that was a great reminder,

and it really provided me in the film with this kind of stillness and, you

know, ease with everything.

GROSS: I sometimes think about what it must have been like for you and Ricky

Jay, who was also in "The Spanish Prisoner," to work together, 'cause you

used to do magic and Ricky Jay is, you know, one of the great living...

Mr. MARTIN: Right. Well, Ricky...

GROSS: ...prestidigitators? Is that...

Mr. MARTIN: Yes, yes.

GROSS: And, you know, master of card tricks and cons and the lore of magic

and carnivals and--so did you--yeah.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, Ricky Jay and I go way back. We go back to the late

'60s. He...

GROSS: Did you perform on the circuit together or something?

Mr. MARTIN: A bit, yeah. We actually met in Aspen, and he was working

someplace and I was working someplace. And I remember he was a book collector

and I was a book collector. And there was this beautiful rare book called

"The Expert at the Card Table" by S.W. Erdnase. And it was written,

published, I think, in 1907, and it was one of the early books that exposed

ways to cheat at cards. And of course, the author, if he had been known,

would have been beaten up. And S.W. Erdnase is Andrews written backwards,

and that was the real author, and we both sort of fought over a copy of that

book once.

GROSS: Who won?

Mr. MARTIN: I bought it, and then I gave it to him...

GROSS: Oh, you're so generous.

Mr. MARTIN: ...years later. Yeah.

GROSS: Do you remember the point in your career when people started to

realize, `He's smart'? You know, 'cause you played kind of stupid, you know,

wacky personas, right? And then eventually people realized, `God, he's really

smart.'

Mr. MARTIN: Well, you know, it's something you can never say about yourself

and believe it...

GROSS: Right

Mr. MARTIN: ...that you're smart. And so I don't--you know, I don't think of

myself as smart. I don't know--I mean, I almost feel like if anybody thinks

that, they're being cheated, because I also know people who actually are

really smart, and I've been around them. You know what I am if anything, I'm

diligent. But I've been around people who were smart, and I feel like my

relationship with them is my dog's relationship to me.

GROSS: (Laughs) Your dog's a good audience, let's not forget.

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah. Well, you know, my dog, he gets--you know, if I say, `Go

get the tennis ball,' he knows to get the tennis ball. But if I say, `Go get

the tennis ball and take it upstairs and put it under the bed,' then he's at

the point of `Duh.' And that happens--I find that happening to me when I'm

around really, really smart people, that there's a ceiling I hit of

understanding.

GROSS: And you know, when--you're very funny on stage and on screen as you

are. People expect that you're just going to be, you know, a laugh riot when

you speak in person, too. And did you have to deal with the expectation that

you're just going to be, you know, a real cut-up in person?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, you know, I guess a little bit, but sometimes I can be a

cut-up. You know, there's a...

GROSS: Oh, no, right. No, I realize that.

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah. Yeah. And you know, it's really people who don't know you

who expect that, and I don't really find myself in those circumstances that

much anymore, at least in private circumstances. I'm a, you know, pretty

regular sociable person or social person, so I think I'm--you know, I couldn't

do in private what I did on stage; people would not want to be around me, you

know, if I was that hyper all the time. And, you know, I've kind of worked it

out now, kind of figured out how to be.

GROSS: Well, you've had the responsibility of having to be funny at the

Academy Awards when you were hosting right after the start of the war in Iraq.

Mr. MARTIN: Right.

GROSS: How did you work through in your mind how to handle that?

Mr. MARTIN: I'll tell you, it goes back--I was working--in 1963, I was

working at a theater doing a comedy show at Knott's Berry Farm, California,

and that day Kennedy was assassinated, and everyone was stunned and shocked.

And of course we weren't going to go on. And then the owner said, `We're

going to do the show anyway.' And we just couldn't believe--we didn't even

know how we'd get through it. Well, to my surprise--`This is going to be the

worst show ever.' To my surprise, the audience was riotous; that they wanted

to laugh or something took hold of all of us. And this memory of this tragic

day stuck in my head, and I knew somehow that this could be overcome once the

show started, and all I needed to do was to acknowledge in some way with

exactly the right tone and then get on with it. And it was a tough day,

because I remember just before the show began, I had just turned on the news

for three minutes and turned it immediately off because it was one of the

worst news days for our troops, and, you know, I didn't want to be infected or

know until later. And we went on and did some acknowledgments and then went

through with the show. And I really did feel at one point, I think one of

the writers--I had some great writers with me--said, `They will be watching,'

meaning the soldiers will be watching. And that's when I thought, if I were

they, I'd like to see a good, funny show.

GROSS: So how did you decide what your opening line should be? 'Cause that's

the real icebreaker.

Mr. MARTIN: Oh, that was--there was a line about--I'd looked around at the,

you know, Oscar set, which is always, you know, really overblown and I think I

said something about, `Well, I'm glad they cut back on all the glitz.'

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MARTIN: And, you know, it was just that simple little release, and then I

just went on with the show, you know, just something you think of and seems

like the appropriate moment. It's not hilariously funny or anything, but it

sort of gets you over that hump.

GROSS: What kind of guidelines are you given about, you know, not taking a

stand or saying anything too political?

Mr. MARTIN: None.

GROSS: Oh, really? 'Cause it sounded like the actors were told not to be

overtly political.

Mr. MARTIN: Oh, I think actually they--I don't recall what happened, but I

was given no instruction at all. And you know, what I said and did was

determined solely by me.

GROSS: Any thoughts on Michael Moore's speech?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, you know, we knew he was going to say something if he won,

and so were--it was actually Dave Barry, the great syndicated columnist, who

deigned to help me write some things, along with some other great writers. He

said, `I know Michael Moore, he's gonna say something, 'cause we saw him at

this other thing, and he was this way, and he's gonna say this, and then we

should have something'--but we didn't really come up with a line--you know,

then he did his diatribe, which is--you know, that's what Michael Moore does.

The audience response was mixed. They were booing, a lot of them. And if

they were booing, I think it was because of the inappropriateness maybe at

that moment, and not that they disagreed or agreed; I couldn't tell. I think

the line we had was--oh, yeah, I came out afterwards, I said, `Oh, it was so

sweet backstage; I wish you could have seen it. The Teamsters were helping

Michael Moore get into the trunk of his limo.'

GROSS: So you had that one ready to go?

Mr. MARTIN: No, we didn't have it ready to go.

GROSS: Oh, oh.

Mr. MARTIN: We had it after the fact. And we were watching, we were

watching, we were watching, and then we had a team of writers and it just

spontaneously occurred in the room and that's what we went out with--or I went

out with.

GROSS: Listen, thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. MARTIN: Thank you. I really enjoyed it.

GROSS: Steve Martin. His new novel is called "The Pleasure of My Company."

Coming up, linguist Geoff Nunberg on the rhetoric of color blindness. This is

FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Commentary: Use of the term `Caucasian'

TERRY GROSS, host:

The language of racial classification can seem so complicated and inconsistent

that some people have suggested we simply throw the classifications overboard.

That's the goal of a proposition on tomorrow's California ballot. But our

linguist, Geoff Nunberg, says you may as well try to pass a law to rid the

language of irregular verbs.

GEOFF NUNBERG:

The recall has been getting all the ink, but the item on tomorrow's California

ballot that has the most important national implications is what backers call

the Racial Privacy Initiative, which sharply restricts the state's ability to

classify people according to race. Opponents of the measure argue that it

will hamper efforts to gather information on discrimination, hate crimes and

health questions. But supporters defend it with the new rhetoric of color

blindness. They ridicule the stew of ethnic and racial classifications that

students have to tick off on University of California admissions forms. As

they put it, it's time to junk a 17th-century racial classification system

that has no place in 21st-century America. Well, they're not going to get a

lot of argument on that. But the classification system they want to sweep

away is more of a modern creation than an ancient one. And if the language of

racial classification seems inconsistent and jumbled, that's the fault of the

uneven social landscape we're asking it to map.

Those inconsistencies came to the surface in a recent story about a

15-year-old high school freshman in Oakley, California, who had gathered 250

signatures to start a Caucasian Club. If African-Americans, Latinos and

Asians could have clubs to teach them their culture, as he put it, then why

shouldn't whites have one as well? That logic was plausible to a lot of

people, including 87 percent of the respondents to a poll conducted by a Los

Angeles TV station. Others thought the club was a bad idea, though a lot of

them blamed the multiculturalists for setting a bad example. As the National

Review's Jay Nordlinger put it, `A Caucasian Club, ugh. Enough of the

Balkanization of America.'

Actually, the key word there is `ugh.' There's something about the history of

that quaint word `Caucasian' that makes even conservatives a little squeamish

about seeing it in an organization's bylaws. As it happens, the word is

exactly as old as the American nation. It was invented in 1776 by the German

anthropologist Johann Blumenbach. He chose Caucasian in the belief that the

white race began its peregrinations when Noah's ark landed on Mt. Ararat in

the Caucasus.

By all rights, the Caucasian label should have vanished a long time ago, along

with Mongoloid, Negroid, American and the other categories of discredited

racial theories. One reason why it survived is that it was often used in what

were called the `Caucasian clauses' of organizations and restrictive housing

covenants. But even then, the word wasn't used in its anthropological

meaning, where it included the peoples of the Middle East and North Africa.

It was simply a genteel-sounding way of excluding people of the wrong sort,

whoever they happened to be at the time. As late as 1947, a civil rights

report said that there was no immediate prospect of a mass migration of

Negroes, Jews and other minorities into exclusively Caucasian areas. And when

Jews were reclassified as Caucasians soon after that, it had more to do with

their effects on property values than with any new findings in physical

anthropology.

In fact, the Caucasian label has become even more common in recent years, to

the point where it's part of the active vocabulary of a high school freshman.

That's partly a response for the need for a term to pair with

African-American, another odd entry in the American racial lexicon. When

African-American was popularized in the late '80s, it was supposed to suggest

an identity defined by ancestry rather than by color. But we don't use

African-American the way we use labels like Italian-American, where we feel

free to drop the `American' part when the context makes it clear. We talk

about an Italian neighborhood, but not an African one. The `African' of

African-American isn't a geographical label; it's just a prefix that means

black.

If we were being consistent, we'd contrast African-American with

European-American. But the only people who use that term are scholars and the

modern racialists who have tricked out their programs in the language of

multiculturalism. A couple of years ago, an outfit called the

European-American Issues Forum persuaded the California Legislature to

proclaim a European-American Heritage Month. Instead of European-American,

people use Caucasian, which seems to invest European descent with an objective

scientific standing. That's specious, of course. If African-American is a

racial category masquerading as a cultural one, Caucasian is a cultural

category in racial drag.

But it can be a useful word to have around when you want to make a racial

contrast without risking a charge of vulgar bias. And its scientific-sounding

cachet made it the natural choice for the name of a high school club. To

white adolescents in the California suburbs, the old ethnic identifications

are remote and attenuated, and mere whiteness is apt to strike them as boring.

As that California student put it on CNN, `Well, you ask the kids "What are

you?"; they'll say white, but white, that's not a race.' Actually, she had

that backwards. It's white that's the race and Caucasian that's the cultural

category. But her confusion was just an outgrowth of the language of race

itself.

We're always struggling to find racial labels that answer the question `What

are you?' with evenhanded essences. But the labels keep catching their

sleeves on disparities in the way we think about race itself. Racial

classifications are like irregular verbs; they may be inconsistent, but they

run too deep to eliminate by decree.

GROSS: Geoff Nunberg is a linguist at Stanford University's Center for the

Study of Language and Information, and he's the author of "The Way We Talk

Now."

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.