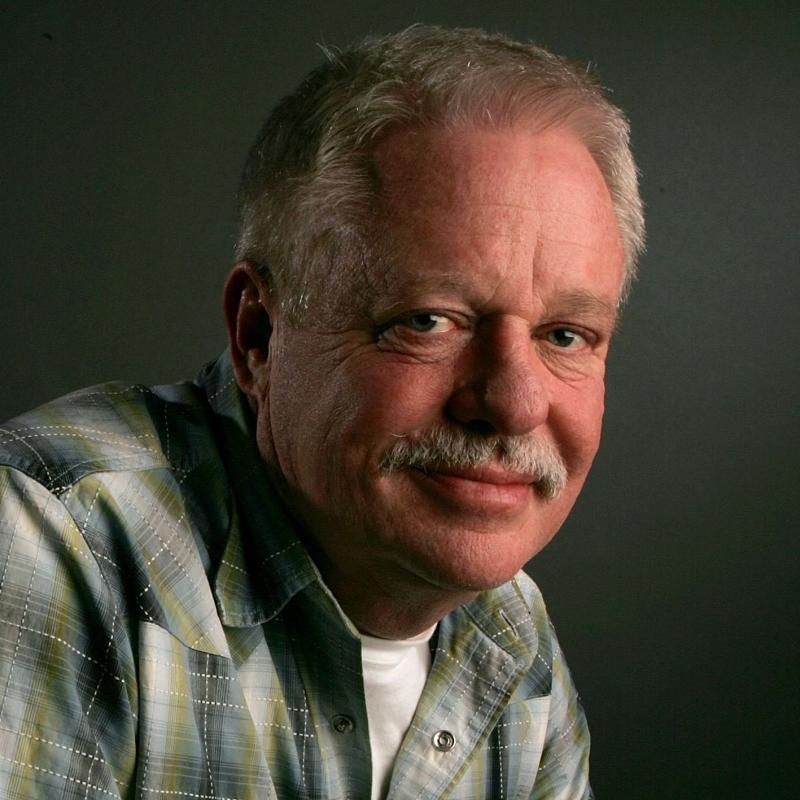

Writer Armistead Maupin Discusses His New Novel.

Writer Armistead Maupin, creator of the award winning newspaper serial turned TV series “Tales of the City”. Maupin's new book “The Night Listener” (Harper Collins, 2000) is his first novel in eight years. It examines the relationship that grows between a cult writer and one of his younger radio fans; critics have noted the autobiographical subtext to the story. Maupin won the 1998 Peabody Award for his work in television and has written several novels and two collections of essays. He lives in San Francisco.

Other segments from the episode on October 3, 2000

Transcript

DATE October 3, 2000 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Armistead Maupin discusses his new book "The Night

Listener"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Armistead Maupin is best-know for his "Tales of the City," which started as

a

story serialized to newspapers and was expanded into several best-selling

novels and two TV miniseries, one of which won a Peabody Award. The stories

were set in San Francisco and revolved around a group of gay and straight

friends of different generations. Maupin's new work is a

semi-autobiographical novel called "The Night Listener." The main character,

Gabriel Noone, writes stories very similar to Maupin's "Tales of the City,"

but Noone serializes his stories on the radio, in fact, on NPR. Noone's

life

has changed as one person leaves him and another enters his life. The

person

entering his life is Pete, a 13-year-old fan who has written a

not-yet-published memoir about being abused by his parents. The person

leaving Noone is his longtime lover Jess, a character based in part on

Maupin's former lover, Terry Anderson, to whom the new novel is dedicated.

Let's start with a short reading.

Mr. ARMISTEAD MAUPIN (Author, "The Night Listener"): (Reading) `I wasn't

myself the afternoon that Pete appeared. Or maybe more severely myself than

I

had ever been. Jess had left me two weeks earlier and I was raw with the

realization of it. I have never known sorrow to be such a physical thing,

an

actual presence that weighed on my limbs like something wet and woolen. I

couldn't write or wouldn't at any rate. Unable to face the grueling

self-scrutiny that fiction demands. I would feed the dog, walk him, check

the

mail, feed myself, do the dishes, lie on the sofa for hours watching

television. Everything seems pertinent to my pain. The silliest coffee

commercial could plunge me into profound Jacobean gloom.

`There was no way around the self-doubt or the panic or the anger. My

marriage had exploded in mid-air, strewing itself across the landscape. And

all I could do was search the rubble for some sign of a probable cause, some

telltale black box. The things I knew for sure had become a litany I

recited

to friends on the telephone. Jess had taken an apartment on Buena Vista

Park.

He wanted space he said, a place to be alone. He had spent a decade

expecting

to die, and now he planned to think about living. He could actually do

that,

he realized, without having to call it denial. He would meditate and read

and

focus on himself for once. He couldn't say for sure when he'd be back or if

he'd ever be back or if I even want him when it was over.

`I was not to take this personally he said. It had nothing to do with me.

Then after stuffing his saddle bags full of protease inhibitors, he pecked

me

solemnly on the lips and mounted the red motorcycle he had taught himself to

ride six months earlier. I'd never trusted that machine. Now as I watched

it

roar off down the hill, I realized why. It had always seemed made for this

moment.'

GROSS: Thanks, Armistead. That's Armistead Maupin reading from his new

novel, "The Night Listener." I think that pretty well sets the scene as the

main character's lover has walked out on him. A boy enters his life. Who

is

he?

Mr. MAUPIN: He's a boy who lives in the snowy depths of Wisconsin who is a

fan of Gabriel Noone. Gabriel Noone himself is a radio storyteller, a man

who

tells stories on NPR, as it happens, late at night, and has a bit of a cult

following around the country. And this little boy, who's 13 years old, has

fixated on the storyteller in such a way as to think of him in paternal

terms.

He hears this voice and relates to him. The child has a horrific past of

sexual abuse. And he connects with this storyteller in such a way that the

two of them are able to unload their hearts to each other, as it were.

GROSS: Their connection is really on the telephone 'cause they're in

different places.

Mr. MAUPIN: That's right.

GROSS: And Gabriel is somebody who never really wanted to be a father

figure,

but he's becoming a father figure to this young boy. What are the most

pleasant surprises for Gabriel about becoming a father figure?

Mr. MAUPIN: I began to pursue this particular story line because at the age

of 50 or so, I began to realize that I was actually having paternalistic

feelings about other people in my life. I really can truly say that I

myself,

like Gabriel Noone, have never wanted to have a child. I've never missed

that

because of the life I've led as a gay man. But I do have feelings that

approach paternalism that I felt towards, in particular, a godson that Terry

and I have up in Inverness County--up in Inverness, Marin County, that we've

both known since he was seven years old and remarkably mature kid that has

had

amazing conversations with me. When Terry and I broke up, it was Nick--Nick

was the one that we needed to explain ourselves to. And there have been

other

people in my life--gay men--younger gay men who--towards whom I feel this

different kind of love that I've never really expressed, because I haven't

been old enough to express it, or I haven't had children.

GROSS: Now one thing that Gabriel, your character, runs up against is that

he

starts thinking that this boy he's communicating with on the phone might not

actually exist.

Mr. MAUPIN: Yes. I hope we won't go too much beyond this in the

discussion.

GROSS: That's about where I was going to end.

Mr. MAUPIN: Yeah. I want this thing to be a ride for people. "The Night

Listener" kind of grew out of a feeling that I've had for many years, that I

wanted to write something that accomplished what "Vertigo" did for me when I

was 14 years old, the age of Pete, as it happens. I was so overwhelmed by

this film that was about passion and obsession and love and loss, this deep

loss, sense of loss that was all wrapped up in a mystery story, that for

years

I thought I would really love to accomplish the same thing, a sort of

thriller

of the heart that compels people to read, because a mystery is unfolding but

digs rather deeply into the human condition and reveals things about the

soul

of the writer, and hopefully the souls of the readers.

GROSS: Now Gabriel, your main character, does this radio serial. Did you

make him a radio person so that Gabriel would be an invisible presence in

people's lives, just as this boy is a kind of invisible presence in

Gabriel's

life?

Mr. MAUPIN: I did. That's very observant of you. That occurred to me into

the--well into the writing of it, that this was really about voices. It was

about the way in which voices soothe us and seduce us and allow our

fantasies

to grow.

When I was a kid and listened to radio serials back in the early '50s in

North

Carolina, they stimulated my imagination in a way that it hasn't been

stimulated since, because television and film basically are about staring

into

boxes. But voices can do anything. They can go anywhere and be anything,

and

we can construct whole worlds around them, because we have to, because

there's

nothing else there. You must have found this yourself, with people

imagining

things about you, just from hearing your voice on the radio.

GROSS: Yes, and they're always surprised when they meet me, because I look

nothing like the way they've constructed me in their minds.

Mr. MAUPIN: And it's something that can work very well in the context of a

suspense novel, because novels are about words, and we build those voices in

our heads as we read, and we build the faces for those faceless people as we

read.

GROSS: Did writing this book get you listening to the radio any differently

than you usually do?

Mr. MAUPIN: No. It really didn't. It got me to thinking about what it

would be like to perform on the radio. I realize that I've always written

in

order to imagine my future. If there's something that's not happening in my

life that I would like to have happening, I sometimes imagine myself in that

situation before it occurs. I imagined myself as coming out to my parents

in

"More Tales of the City" in a letter that a fictional character wrote to his

parents, and that, in turn, created a situation that enabled me to come out

to

my own parents.

The same thing happened with this novel in terms of my relationship to my

own

father. There is a character in "The Night Listener" who is based on, I

think

I can say safely, my own father, although I put him into completely

fictitious

circumstances, and after he'd read the novel, he called me up about six

weeks

ago, and told me how proud he was, how much he loved me. He completely

opened

up his heart to me in a way that he has not done, and what it did for me was

to make me do the same thing.

We were giggling on the phone to each other the other night like teen-agers.

It was amazing--these two old farts who'd finally reconciled with each other

and were able to accept each other as who we were. So that's what's

happened.

GROSS: What do you think he saw in this novel that hadn't struck him in

your

earlier work that made him open up to you like that?

Mr. MAUPIN: Well, I talk about the way I felt about losing my mother, which

was something that he and I have never talked about, and discussed the

moment

of that loss, and how it affected us both. The novel goes into the suicide

of

Gabriel's grandfather, which is something that was never discussed in the

family--I have a similar situation in my own family. My father said to me

rather touchingly, `I want you to know it wasn't as hard on me as you

thought

it was. I dealt with it. We just didn't talk about those things in those

days.'

So I've always used writing as a way of emptying my own heart to the people

I

love, and I do it through fiction. It's not non-fiction. I mean, it's

really

futile to say what's true and what isn't true about this novel, because it

changes from sentence to sentence. But what I do try to make true is the

emotions, and I have found from long experience that when I write about real

experience, I reach people more directly, because there's a ring of truth to

it that cannot be duplicated in any other way.

On the other hand, I am a completely instinctive storyteller. I want things

to have a shape, to build. I want there to be that eerie moment where

everyone shudders and says, `Oh, no! I can't believe he did that.' That's

my

instinct. That's what I'm happiest doing.

I read a piece recently by Christopher Isherwood in which he talked about

how

he had those two instincts, and they were constantly colliding, and

constantly

getting him in trouble, because people say, `Well, this is true. It must be

true. It must have happened to you.' No, you funnel things through your

own

emotions in order to make it seem true. And once you've accomplished that,

you've reached your purpose.

GROSS: My guest is Armistead Maupin. His new novel is called "The Night

Listener." More after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Armistead Maupin is my guest. He's best-known for his "Tales of the

City" series. His new novel is called "The Night Listener."

You know, one of the things, obviously, that gives your novel the ring of

having some autobiography behind it is the fact that Gabriel, your main

character, is a storyteller, and his stories are serialized on the radio,

much

as your "Tales of the City" stories were serialized in newspapers.

Mr. MAUPIN: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: And he describes his stories in a way that perfectly describes

"Tales

of the City."

Mr. MAUPIN: Hmm.

GROSS: He says, `My characters were a motley, but lovable bunch, people

caught in the supreme joke of modern life who were forced to survive by

making

families of their friends.'

Mr. MAUPIN: Hmm.

GROSS: Perfect description of "Tales of the City."

Mr. MAUPIN: Yeah, I'm having some fun there, obviously. I'd be a very coy

creature, indeed, if I didn't confess that I'm talking about myself there.

GROSS: Is that how you'd always describe "Tales," or did you kind of

crystalize that description for this book?

Mr. MAUPIN: No, I'd pretty much described it that way for a while. I had a

pretty strong sense of what I was doing with "Tales." And I must say I've

come to approach Gabriel Noone even more than when I began to write the

piece

because "The Night Listener" was the first novel ever to be serialized on

the

Internet in audio form prior to its publication. Salon.com has been running

it as a serial. It's also available as an unabridged CD. And so, in

essence,

I became Gabriel Noone in the actual recording of the novel, so that was

kind

of a thrill for me.

As you can tell, this whole novel is about the blurring between truth and

fiction, and what are we to believe in the end? How do we tell stories to

save our own lives? Because we all do it. Not just storytellers, every

person on the planet anecdotalizes his own life in order to explain himself

to

himself and to other people. And this is about how are we to believe those

stories. Who are we to trust? Gabriel Noone tells you from the very

beginning that he's an unreliable narrator. He says, `I'm a fabulist by

trade. I've spent my life looting my life for fiction, and I only save the

shiny stuff.' Well, that's a description of what I do. My memory of my life

is not accurate. I have only memories of stories that I have constructed

out

of my life. And the people who know me know this about me. I've tried to

be

fastidiously honest about who I am throughout my career, and to open up my

heart as much as possible. But when it comes to storytelling, I'm really

not

to be trusted.

GROSS: Now in the book, Gabriel's long-term lover has just left him. Jess,

his lover of about 10 years, has had AIDS for several years. But after he

starts taking the AIDS cocktail, when it appears his life will be longer

than

he expected, he leaves Gabriel. Why does he leave?

Mr. MAUPIN: Well, I couldn't even begin to analyze that beyond what's

written

in the book. But I think what I was trying to capture there was a very real

phenomenon that has happened because of protease inhibitors, people who

thought they did not have a life suddenly have one. And there are enormous

options that are open to them, and they want to be able to exercise those

options.

I can't speak for Terry--I mean, I won't speak for Terry. I probably could.

I know his so well, and we still love each other so much, but I know that he

felt that--Terry felt when he left that he needed the chance to find out who

he was separate from me now that he knew he was going to live. And because

I

was so socked into this cozy domesticity and used it to make myself feel

secure and safe about myself, things--you know, my own sense of who I was

fell

apart.

The amazing part about this story is that that first chapter, the one I just

read from, I was writing while I was in the midst of that pain. And the one

person who was encouraging me to write it was Terry. He said, `This is what

you do. Put it down on paper. Say what you feel. I don't care what you

say,

just put it down.' And then when the novel began to happen at Terry's

encouragement, he was always the one who came back to me and said--as he has

said for many, many years--`Oh, you're just at that point where you think

it's

no good, but you've got to keep writing.' And, of course, he's been the one

to promote and to--I mean, we remain business partners and family in the

most

extraordinary, loving kind of way. I can say with real honesty that we have

more love and respect for each other than--even then we had when we were

romantically involved. It's been four years since we split, and it gets

better every year because we know it's permanent now.

GROSS: You know, your character, Gabriel, is so upset when his lover, Jess,

leaves, and realizes that he'd been imagining that Jess would have died in

his

arms. And that, in fact, he'd been planning, even romanticizing, Jess'

death

to conceal the horror of losing him. Is that something you realized you'd

been doing, too?

Mr. MAUPIN: Yes, absolutely. I did realize that. And that was one of the

hardest things to write about. We all have to find ways to contain what

pain

we think is on the horizon for us. And for me, it was the thought of losing

Terry. It was enormous. And there had been models of this--you know, Paul

Monette's extraordinary account of the death of his lover, Roger, in

"Borrowed

Time." The people who were writing non-fiction at that time were really

capturing something extraordinary, the love between two men, where one of

them--or maybe both of them, has a limited amount of life left. So in some

way, I was embracing it long before I needed to. I mean, wasn't that the

great, profound, sort of cosmic joke of protease inhibitors? This thing

that

people assumed was final and for so long proved not to be.

You know, people used to say to me that they were certain that I stopped

writing "Tales of the City" because Michael Tolliver had been described as

being HIV-positive, and they knew that I couldn't write anymore because he

would be surely be dead by now. And that used to really bother me because

Michael tested positive at the same time Terry tested positive. It's why I

made Michael positive. And Terry was still alive, and Terry is still alive

after all these years. And this terrible thing that we assumed would happen

did not happen. So there's a message even in that: that you can't count on

anything. You can't count on death, and you can't count on life.

GROSS: Do you think there's the sense within a relationship when you expect

that someone won't be able to survive for very long, that that means neither

one of you will have the opportunity to betray each other so that there's

this

kind of trust that maybe goes beyond what regular relationships have because

time is so limited and you expect never to be betrayed?

Mr. MAUPIN: There may be. I don't think that's a fair assumption to make

about any relationship. I mean, the possibility of one person dying

shouldn't

really change the nature of the relationship. I suppose that the safest

thing

I could say about is that when you think that somebody is going to die, you

don't spend a lot of time being bored with each other.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MAUPIN: And in some ways, that was an amazing feature of that

knowledge.

We packed our lives full of things to do. We took trips. We went to Lesbos

with our friend, Steve Beery, who died six years ago. We bought a farmhouse

in New Zealand to have the experience of it, to know what it felt like to

live

out in the country and to be separate from the world. We found out, and

sold

the farmhouse. But...

GROSS: What didn't you like about that?

Mr. MAUPIN: The commute was a killer, you know. It was a very--you know,

it

was a 14-hour plane flight, and it got to be rather existential. We were

shipping hundreds of books to New Zealand and, you know, really setting down

roots there in a very odd way, given that we felt Terry had a very limited

amount of time. But I'm so glad we did it. And it's a lesson to be

remembered about life now. We still have to seize the moment even when we

think we have--we're pretty sure we have more moments than we counted on.

GROSS: Armistead Maupin will be back in the second half of the show. His

new

novel is called "The Night Listener." I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH

AIR.

(Credits)

GROSS: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

Coming up, staying friends and business partners after no longer being

lovers.

We talk with Armistead Maupin about the relationship that inspired part of

his

new novel. And Maureen Corrigan reviews "When We Were Orphans," the new

novel

by the author of "The Remains of the Day."

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross back with Armistead Maupin.

He's

best known for his "Tales of the City," which started as a newspaper serial

and was expanded into a series of novels and two TV miniseries. His new

semi-autobiographical novel is called "The Night Listener." It's about a

writer who serializes his stories on the radio. His life is changed when

his

long-term lover leaves him, and a mysterious 13-year-old fan enters his

life.

This novel seems to me, in part, to be about the main character's

insecurities. And maybe I'm reading too much into it, but I figure perhaps

they're some of your insecurities as well. For instance, the writer in your

novel says `If Jess could walk out on the myth he'd help create, the real me

must be someone truly unlovable.' And like the lover in your novel, Terry,

who was your lover for many years and remains your business partner, really

helped you in all the business aspects of writing.

Mr. MAUPIN: Yeah. Yeah.

GROSS: Marketing the books; setting up the Web site; getting the deals,

plus,

you know...

Mr. MAUPIN: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...reading the fiction and commenting on it and giving you

feedback--I

mean all of that. So is that, like, an insecurity that you feel you shared

with your ...(unintelligible) or...

Mr. MAUPIN: Well, yeah, to a certain degree. We go all sorts of dark

places

when we're breaking up with someone. There's no question about that. And I

think that was my way of reminding myself not to believe in that myth. I

think the hard part was losing the reality of my life temporarily, in terms

of not having that daily reinforcement from Terry. To this day I value most

the people I love; my little circle of friends. That's the real thing for

me. When this sort of madness of publicity tours descends upon me and I

feel

really alienated from myself because I feel that I'm a commodity on some

level, I retreat to the sort of bedrock knowledge of that; that I'm loved by

people who actually know me; who know who I am, because I'm never fully

convinced that my readers completely understand who I am, warts and all. I

probably have a way of glamorizing myself to such a degree that I don't feel

that they totally know who I am. So, yeah, there was some of that

insecurity.

I have heightened all of Gabriel's insecurities. I mean, I took mine and

went

even deeper. There's a place in there where Gabriel says he feels his--that

he might have broken into the temple of literature through an unlocked

basement window. Well, that's a little bit the way I feel about having

become

a novelist by way of a daily newspaper serial. But it's--would be a little

disingenuous to say that that's completely how I feel. I know that I'm

good.

I mean, I know I've worked very hard to become a writer over the last 25

years. And I know what I know how to do. So I'm not that insecure. But,

you

know, your lead guy needs to be neurotic. It's more interesting. I mean,

that's what Jimmy Stewart tells us about "Vertigo." That film is so

interesting to me today, still, because I'm the age that Jimmy Stewart was

then, and I get it. I see what's going on and I realize how complicated

this

mystery story becomes because of his neurosis.

GROSS: You know, one of the things I love about "Vertigo" is that it's

about

finding what you think is your ideal in another person, realizing that that

person doesn't quite exist, but forcing them to become that ideal that

you've

constructed.

Mr. MAUPIN: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

GROSS: You know, forcing somebody to be the person who you've imagined them

to be...

Mr. MAUPIN: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...or you've been misled into thinking that they are.

Mr. MAUPIN: And there's, of course, a parallel for that in "The Night

Listener."

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MAUPIN: And--where Gabriel has to ask himself, `Does it matter? Does

it

really matter who I'm talking to, in the end, if I've connected in some

way?'

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. MAUPIN: And I think the nature of love--I mean, what I've come

through--I

mean, what I've really learned out of the experience of losing someone that

I

lived with for 10 years--or least thinking I was losing him was that when

all

else was stripped away; when the coziness of our domestic life was gone;

when

we weren't sleeping in the same bed; when I couldn't count on him being

there

every day, I was left with the love that we had for each other. And it was

still there. It was in the room with me. And so we found a way to work

through this. There was an account in the San Francisco Chronicle--a very

crude account trying to link "The Night Listener" with my own life and ended

up making it sounding like an `airing of dirty laundry,' I think was the

term

they used--almost as--like a vindictive act. Well, anyone who's read the

novel realizes that it's really about how two people make it through to the

other side; how love becomes permanent.

GROSS: What's it been like for you to be single again?

Mr. MAUPIN: Freeing, in many ways, especially since I still feel the

connection of family to Terry and the people I love. I don't feel alone in

that regard. But there's suddenly the opportunity to look at people on the

street and think, hmm, you know, or talk to somebody at a book signing and

ask

him out for a drink afterwards. And, you know, it's a second childhood, of

sorts. I'm rather enjoying it. And I--the pressure's off somehow. I've

had

my great love. I did it. It's still here. I know what that domestic thing

felt like and it was great most of the time. Don't get me wrong. I loved

it.

But at the same time, it's kind of nice to have the house to myself at

times;

to know that I don't have to, you know, discuss with another person what

we're

going to eat that--for dinner or where we're going the next day or how we're

going to spend the weekend. There's a certain amount of freedom to be found

in that.

GROSS: You know, Armistead, I know that as we're talking that Terry

Anderson,

who is the inspiration for the Jess character in your novel--he's your

former

lover and still business partner. He's been in the control room the whole

time listening to the interview.

Mr. MAUPIN: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: So I was wondering if would be OK if we, maybe, invited him to the

studio so I could ask him a few things about what it's like to be the

inspiration for a character in your novel.

Mr. MAUPIN: Sure, it's OK with me. Well, it looks like--yeah, he's

signaling

that he'd be glad to, so...

GROSS: Well, why don't we take a break here while Terry comes in? And

we'll

be back with Armistead Maupin and Terry Anderson after a break. This is

FRESH

AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is Armistead Maupin, and he's the author of "Tales of the

City." His new novel is called "The Night Listener." And one of the

characters in the novel, the character of Jess, is inspired by Armistead's

former lover and still-business partner, Terry Anderson, to whom the book is

dedicated. So we've invited Terry in to the studio.

Terry, welcome back to FRESH AIR.

Mr. TERRY ANDERSON: Well, thank you, Terry. It's good to hear you again.

GROSS: Terry, I'm wondering what it's like for you to have--to be the

inspiration for this character who's the cause of a lot of pain in the novel

because this character has walked out on the main character. There--he no

longer wants to be lovers. He wants to kind of explore a little more

independently his own life now that he knows he's gonna live longer than he

expected as a result of the new AIDS drugs. So what's it like to have

inspired this character and to read it in the novel?

Mr. ANDERSON: I think inspired is the operative word because there's...

GROSS: It's not you.

Mr. ANDERSON: It's not me. It's not me. Rumors of my piercings are

greatly

exaggerated. There's some similarities, you know. Yes, I have gone through

a

life-altering experience of thinking I was going to die and then giving it a

reprieve, which is a--profoundly changed the way I view the world. So

it's--I

was glad to have Armistead have an outlet for it creatively. I think I

revere

writers and I revere the creative process, so I never wanted to interfere

with

it.

Unlike his other novels where he's read them to me as he's written them, I

asked that he not let me read this until he finished it because I did not

want

to get in the way. If I saw something that really made me cringe, I didn't

want to be responsible for ruining his process. So I sort of said, you

know,

`Finish the book. Let me read it. And then I'll take what I don't like

out.'

So there's things that are very different about the two of us, but there's

some very--I think an emotional truth that's present in both of us. I mean,

we have this profound experience of saying, `Hey, I'm not going to die. And

what do I do with my life now.'

Mr. MAUPIN: And I could have never have written the novel if he had not

given

me that permission; if he could--if he had not said, you know--given me the

freedom to work all the way through it. And it was very strange because I

didn't know what the end of it was. I was in the middle of the--of my

feelings when I was first trying to write it. And I thought--and much as

Gabriel is, he keeps--throughout the novel; throughout "The Night Listener"

he

says, `How could I live this story if I don't know what the ending is?'

He's

so used to constructing things for himself. And for once, he doesn't have

an

ending.

Mr. ANDERSON: I think it's a risk that you take when anytime you get

involved

with a creative person--anybody who gets involved with a creative person

runs

the risk of having their life looted. And I--by the time this book was

written I knew full well that that was possible. It's always been the way

it's been. I mean, we've been lesbians in one book and, you know, gay

couple

in other books. And, you know, if he writes a book about dogs, next, I'm

sure

we'll be puppies or something. But it's what you do as part of the process.

You know that he has to have some of his source material. And if I can be

that, then I'm flattered.

GROSS: Did you ever feel while you were reading the book the first time

like

saying to Armistead, `Oh, sure. That's your interpretation of it. But

that's not the way I saw it. Here's the way I saw it.'

Mr. ANDERSON: Well, you know, the whole book is one side of a story. I

mean,

it has to be the way it works--is that a fiction writer writes about his

experience. It's not my experience. So I know that that's always going to

be

his side of a story, and a good side. It's a love letter to me. I mean, I

feel very flattered that he has written such a sweet book that's a fun read.

It's not--you know, I don't take it--how do I say this? Without sounding

like, you know--a bitchy quality to it. It's not. It's a very loving

portrait. It's still one side of a story.

GROSS: Has it been at all difficult for you both to remain professional

partners and good friends and not be lovers? I mean there's a lot of former

lovers who--you know, it's kind of all or nothing at all.

Mr. MAUPIN: It's not that way with us. In the beginning it was tough to

sort

of sever that part of it; to sort of say, `OK,' you know, `the romantic part

of it will not be there.' But the reality was that we were always linking

up

and crying all over each other or holding hands or hugging or--we still do

that. We still connect in those ways. We are still two deeply loving

people.

And it's--I treasure that we've come through to the other side.

Mr. ANDERSON: Armistead and I are and remain soul mates. We have always

been. I think we were before we even met, frankly. We know what each

other's

thinking. We know each other better than anybody. I'm involved with

someone

else that I'm very much in love with now. And I sometimes worry about how

he

will fit--feel like he fits into us because we are such a couple. Armistead

and I will always be a couple.

I think the funny thing about breaking up was our friends' reactions to it,

saying, `Oh, you can't possibly break up. You're the best couple we know.'

And then the sort of, frankly, asinine kind of assumptions they'd make about

how you're supposed to break up. `You can't talk to him. You can't

possibly

have any connection with him 'cause you have to have time to grieve it, you

know. Don't even talk to him. Cut off all relations.' We didn't do it

that

way because we know each other. We know--there's a core at which--there's a

core level of love that is important to us. And we--that's something we

believed in even when the romantic part or before my own needs changed or

whatever--for whatever reasons I left, which are numerous and far too

personal

to go into, we didn't do it by the book. And that was part of the thing

that

sort of threw our friends.

Mr. MAUPIN: Well, not our close friends. Some of them. There was a

difficult time, I think, for a while. But I think most people understand it

now. It's--the opportunity to be able to love the people that Terry loves

is

something that I've discovered. I mean, we were--Terry and I were in London

on a book tour. And it was late and night and we were sort of

trying--feeling

slightly insane in the way you do when you're on book tours. And Terry got

on

the phone to his boyfriend and started talking to him. And I suddenly

wanted

very much to get on the phone and tell the boyfriend that Terry had been

talking about him to other people and that he missed him. And I knew that

it

was important for him to get back to him. And I--there was a time when that

would have been unimaginable to me that I could pull that off. And it

wasn't

an effort this time. It was something that I truly wanted because it just

meant that the love was going off in that many more directions.

Mr. ANDERSON: I think people paint themselves into a box a lot around

relationships about how they're supposed to be. And to stop doing that and

look at how you want to live your life free of all the societal expectations

is a great freedom. And I feel very lucky that--I think that's part of

being

gay is that view of being an outsider--is that it allows you to not view

things within the box and sort of notice the paradox of life, you know--how

you can still love somebody but not want to live with them, you know. It's

about expanding your notions of what relationships are. That's been the

best

part of this whole thing with Armistead is we've been able to maintain a

very, very solid relationship even though it's changed forms.

GROSS: Was separating made any more difficult by the fact that you are a

pretty well-known couple? You know, because you were together; because

you've

done a lot of book tours together--you know, you're--you know, you're a

pretty

well-known couple...

Mr. MAUPIN: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...and so you have this, like, image to live up to.

Mr. ANDERSON: Yeah.

GROSS: And then if you decide to separate, it's like, well, you know,

doesn't

the public have a vote?

Mr. MAUPIN: No, they don't. That's the great thing about our lives. I

mean,

what's going on between us is the strongest thing in my life. It's stronger

than my career.

Mr. ANDERSON: There was a pressure on me, to be honest with you when I

started thinking `I need to stretch my wings. I need to have some time to

myself.' I was thinking of the number of people I would disappoint. We

have

a friend who's an actor--Broadway actor who, when I called him to say that I

was doing this, he's like, `You're my heroEs. You can't be breaking up.'

It

was a very odd position to be in to sort of have to make that consideration.

You know, when Ellen DeGeneres and Anne Heche--I just read that they were,

you

know, breaking up. I thought, `I understand the pressure they must--they

both

must have felt about being a symbol. Not simply being a couple. I'm not

allowed the freedom of just being a couple in a relationship, but also to be

a

symbol of something larger. And we were that for some people. And as

flattering as it is, there was a pressure on my part to sort of say, `Stay

with it longer,' to not hurt Armistead and also not hurt a larger public.

GROSS: Terry, when you read a novel like "The Night Listener" by, you know,

a person who you're so close to, do you read it differently than you read

another novel? I mean, are you...

Mr. ANDERSON: Yes, with one eye closed.

Mr. MAUPIN: That's sort of the way I read it, by the way. In the past I've

always had great luxury in sort of flipping through my novels and enjoying a

paragraph that I'm especially proud of or something. And with "The Night

Listener" it's a little bit harder because there was stuff that gets so

close

to times when I was hurting that I just don't--it's hard to do. The first

read of this novel was that way. I really had to sort of like put it down

and

come back to it a few times. It gets easier after you sort of get some

distance on it because I realize that no one has the personal investment in

the material than I do because there are some very autobiographical parts of

this book. So it is bound to strike me--I can rake over it with a

fine-tooth comb much better than anyone else can, so I have to remember than

when I read it.

But upon the third reading of the book when we were sitting down to do the

audio version of it and deciding what was going to stay in and, you know,

what

was going to go and how are we going to produce it, I though, you know, it's

a

good book. It's a good yarn. I'm glad to be a part of it and it doesn't

seem

as--I don't flinch quite as much on the second reading.

Mr. ANDERSON: And I told him that Russell Crowe could play him in the

movie,

so he's...

GROSS: When you and Armistead--Terry, when you and Armistead broke off and

you decided, you know, you needed more freedom and some independence and

probably also to figure out who you were outside of that orbit, did you want

to leave the business, too, temporarily and just have a business that was

separate from that relationship?

Mr. ANDERSON: No, I think I've had--I felt invested in our relationship and

the business as well. We've been so linked in that way for so long. I know

it. I've been doing--I've been working in this field--"The Maupin

Fields"(ph) for a lot of years now, you know. So it would be like starting

over. My mid-life crisis did not involve a career change.

GROSS: Armistead, given how complicated semi-autobiographical fiction is,

do

you think you'd ever write a memoir?

Mr. MAUPIN: No, ma'am.

Mr. ANDERSON: I hope not.

Mr. MAUPIN: Please, no. Well, you know, there's the--that's why I like

fiction. A memoir really does require the truth in a major way. And what

is

the truth when it comes down to your memories? It's a completely subjective

thing. At least I have a certain remove in "The Night Listener." I can say

these are fictional characters. This is about two people that I've

invented.

Terry and I have even, actually, come to see them that way. You can get

some

distance on it. But when you're writing an autobiography, you've really got

to get every single thing right. And the hardest thing about writing this

book, for me was I was desperately afraid that I would hurt someone that I

loved, and that includes just about everybody in the book. I'd--I really--I

wanted to tap the truth of those emotions, but I did not want to hurt a

single

soul in the process of doing it.

GROSS: Well, I thank you both very much.

Mr. MAUPIN: Thank you.

Mr. ANDERSON: Thank you, Terry.

GROSS: Armistead Maupin is the author of the new novel "The Night

Listener."

The novel is dedicated to Terry Anderson.

Coming up, Maureen Corrigan reviews a new novel by the author of "The

Remains

of the Day." This is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: Kazuo Ishiguro's new novel "When We Were Orphans"

TERRY GROSS, host:

Novelist Kazuo Ishiguro has said that he thinks nostalgia is an underrated

emotion. In his novels, including the best-seller "The Remains of the Day,"

Ishiguro explores the rewards as well as the destructive powers of

nostalgia.

Book critic Maureen Corrigan has a review of his latest meditation on

nostalgia, a novel called "When We Were Orphans."

MAUREEN CORRIGAN:

For the first 200 pages or so of Kazuo Ishiguro's "When We Were Orphans," I

felt like I was in the presence of greatness. Then the novel wobbled.

Lurid

surrealism replaced elegant ingeniousness and I had my doubts. Then the

story

righted itself. And, honestly, I delayed reading the final three pages for

an

entire day because I was so reluctant to leave the world Ishiguro had

created.

If "When We Were Orphans" is, as I think, a lightly flawed masterpiece, even

its imperfections are interesting because they're the consequence not of

laziness or lack of skill on Ishiguro's part, but of the kind of high-stakes

gambling with literary form that only restless, serious writers are willing

to dare.

As he proved in "The Remains of the Day," Ishiguro has nailed the voice of

the

self-deluding, first-person narrator. Our specimen here is named

Christopher

Banks, and when the novel begins in 1930, he's established himself as one of

England's great detectives. Ishiguro is paying homage to Agatha Christie,

Dorothy Sayers and other golden-age mystery writers. It's evident from the

way his own novel unfolds that he recognizes the classic detective novels

written between the wars were not mere puzzle stories, but in a fumbling

way,

idealistic, fictional attempts to set the world right. And that's what

Christopher attempts to do on a personal and global scale.

Generous chunks of Christopher's erratic narrative are devoted to his

strange

childhood in Shanghai during the early years of the 20th century. His

father

was employed by a British import-export firm that made a dirty fortune in

opium. And probably, his beautiful mother became a zealous campaigner

against the opium trade. The foreign colony in Shanghai where Christopher

grew up was a contained paradise. And Ishiguro devotes enchanting passages

to the games of make believe that Christopher indulged in with his best

friend, a Japanese boy.

Christopher's quaint life abruptly turned horrific, however, when first his

father and then his mother disappeared. He was shipped back to England by

the firm and raised in boarding schools. As a grown man and professional

detective, he vows to return to China during the Sino-Japanese war to tackle

his greatest, unsolved case, the mystery of the missing parents.

As I said, Ishiguro has nailed the voice of the self-deluding, first-person

narrator. And it's that voice of Christopher's, stiff, wistful, deferential

and defensive that makes this novel so effecting. It's also a voice that's

hard to capture in a quote because Ishiguro's genius lies in modulation; the

way over several pages he'll emotionally shade Christopher's monologue

from, say, a tone of vivid excitement to gray restraint. Here are some

snippets from the long section of the novel where Christopher recalls the

moment he discovered his mother was missing. The woman May Lee(ph) he

refers

to was his nanny.

`The house appeared to be empty. Then, as I was standing bewildered in the

entrance hall, I heard a giggling sound. As I peered in the doorway, May

Lee

looked at me and made another giggling sound. It dawned on me then that May

Lee was weeping, and I knew, as I had known throughout that punishing run

home, that my mother was gone. And a cold fury rose within me toward May

Lee,

who for all the fear and respect she had commanded from me over the years, I

now realized was an imposter; someone not in the least capable of

controlling

this bewildering world that was unfolding all around me. I stood in the

doorway and stared at her with the utmost contempt.'

If nothing else, that passage perhaps gives you a sense of the nightmarish

aspect of "When We Were Orphans." Throughout the novel, Ishiguro

relentlessly

makes the familiar strange. When Christopher returns to Shanghai as an

adult,

his childhood home has been remodeled. Whole floors and stairways moved. A

slum section known as `the Warren' transforms into a mythical underworld for

Christopher; a Homeric hell he fights through to find his parents.

Even the genre of this faux detective novel mutates into other period forms

such as the cliff-hanger serial, the Eric Ambler-type spy thriller, the

society romance. Not all these mutations make sense, and yet even when this

story occasionally became too weird for my tastes, it remained absolutely

emotionally absorbing. The most absurd scene of all, where Christopher

wades

through bombed-out building after bombed-out building in Shanghai to reach

the

house where, he's convinced, his parents are still being held captive after

30

years, well, that's the scene I can't stop thinking about. When somebody we

love dies, we often say `we lost that person.' In "When We Were Orphans,"

Ishiguro, a master at mimicking and probing polite speech, uncovers the

terror

of grief and the raw yearning glossed over in that polite metaphor.

GROSS: Maureen Corrigan teaches literature at Georgetown University.

(Credits given)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.