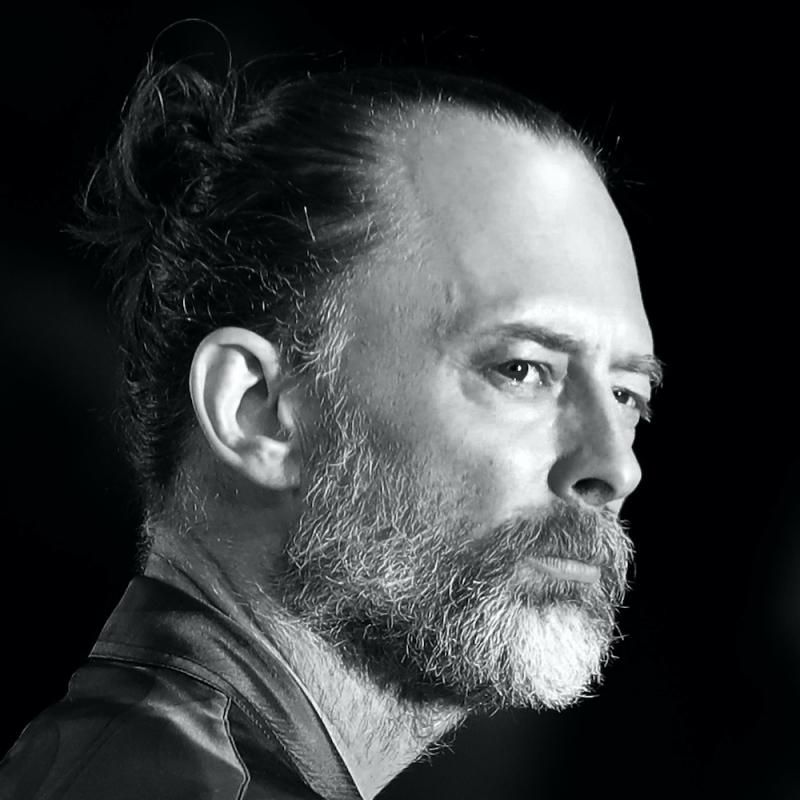

Thom Yorke's 'The Eraser'

Thom Yorke is the lead singer and songwriter of the band Radiohead which has released six critically acclaimed records and explored the boundaries between rock and electronic music. Spin magazine named Radiohead's OK Computer the number one album of the past twenty years. Thom Yorke's new solo CD The Eraser is his first release without the band. This interview originally aired on Jul. 12, 2006.

Other segments from the episode on December 28, 2006

Transcript

DATE Decmeber 28, 2006 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Thom Yorke of Radiohead discusses his depression, the

band's "electronica" influence, and his solo album

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross with another edition in our holiday week

series of music interviews. Up first today we have Thom Yorke, the main

songwriter and lead singer of the British band Radiohead.

When rock critics write about Radiohead, they often use the words "best" and

"greatest." A review in Time magazine was headlined "Radiohead may just be the

best band in the world." Last year, Spin magazine named their 1997 album "OK

Computer" the top album of the past 20 years. Radiohead's latest album, "Hail

to the Thief," came out three years ago.

They're currently at work on their seventh album.

This year, Thom Yorke came out with a solo album called "The Eraser," which he

and the band's long-time producer Nigel Godrich made largely on computers.

New York Time's music critic Jon Pareles put it on his year's top 10 list.

Let's start with a track from Radiohead's "OK Computer." This is "Paranoid

Android."

(Soundbite of "Paranoid Android")

Mr. THOM YORKE: (singing) Please could you stop the noise,

I'm trying to get some rest

From all the unborn chicken voices in my head

What's that?

I may be paranoid, but not an android

What's that?

I may be paranoid, but not an android

When I am king you will be first against the wall

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: When I spoke with Thom Yorke in July, I asked him about the difference

between "OK Computer" and Radiohead's earlier albums "Pablo Honey" and "The

Bends."

Mr. YORKE: When we did "The Bends," we were still figuring out, I think, the

basics even of how to make records. And in the process of doing that, we met

Nigel, who was the engineer on it, who then went and did "OK Computer" with us

and has stayed with us. And then when we did "OK Computer," I think the

difference was that it was like the kids being let loose in the lab, you know.

That's how it felt. I mean...

GROSS: What were you trying that you hadn't tried before?

Mr. YORKE: Well, we bought all our own equipment from some of the proceeds

from "The Bends." And it was all transportable and so it, you know, the

equipment and the concept of recording became part of the creative process

rather than something that was happening in another room over there and we

were just told to `do it again.' So we were trying everything we could think

of, really, within limits. I guess, since then, that's got a little bit out

of hand.

GROSS: So were your musical tastes changing at about this time?

Mr. YORKE: Well, it, I mean, they, you know, they're always changing, and

we're always listening to different things. I mean, one of the most important

things about being in a band, other than just playing together, obviously, is

actually what music you're sharing, what music you're choosing to play to each

other. And around that time there was this series of Ennio Morricone

obsession going on in the band, which really obviously fed, of course, into

the way we were recording.

GROSS: And yet there's no whistler?

Mr. YORKE: No, but there's a lot of pathetic attempts to sort of do similar

sort of things. You know, we bought an old Mellotron and, you know, we're

using lots of those sort of soft distortion like old, you know, deliberately

trying to sort of emulate old recordings, which Nigel is especially good at.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. YORKE: Old recording techniques and stuff, you know.

GROSS: Well, the track I thought we'd play from "OK Computer" is "No

Surprises."

Mr. YORKE: Oh, yeah?

GROSS: Do you want to say anything about writing this?

Mr. YORKE: Well, that's one of the songs that we refer to a lot because,

just in terms of when we're in the midst of a song and we don't know whether

we're just completely wasting our time. And "No Surprises" was like that all

the way through. It was just, `I don't know, I don't know about this.' I

mean, yes, it's a beautiful song, but it just seemed to be too much, too much.

And then gradually sort of chipping away at trying lots and lots of different

things. And then, it's amazing how, as soon as you just got a little bit of

distance from it, as we were finishing the record and placing it in the

record, how powerful it was, really, considering how difficult it was to make.

The nice thing about it, I think, is that you kind of forget about all the

hard stuff. You forget about how difficult it is to do things. Nigel's very

fond of reminding me of that.

GROSS: On "No Surprises"...

Mr. YORKE: Mm.

GROSS: ...was there anything that--any moment where you realized, `OK, this

is actually a good track. This works.'

Mr. YORKE: It was, as often happens, it was actually sort of finally getting

a vocal that made sense, because it was so slow and we had to do sort of--we

ended up, we physically couldn't play it that slow. So it's--we used the old

Beatles technique of record it at the natural speed you want to play it at and

slow it down, and get this sort of strung-out effect. And then singing to

that was just, like, a really quite a weird experience.

GROSS: All right. Well, let's hear the results. This is "No Surprises" from

"OK Computer."

(Soundbite of "No Surprises")

Mr. YORKE: (singing) You were so tired, happy

Bring down the government

They don't, they don't speak for her

I'll take a quiet life, a handshake of carbon monoxide

No alarms and no surprises, no alarms and no surprises

No alarms and no surprises

Silent, silent

(End of Soundbite)

GROSS: That's "No Surprises" from the Radiohead album "OK Computer," and my

guest is Thom Yorke.

Mr. YORKE: Hi.

GROSS: I'm wondering if--I've read this, and I know it's no secret that

you've had--

Mr. YORKE: I have no secrets.

GROSS: ...an issue with depression...

Mr. YORKE: Oh, right.

GROSS: ...over the years.

Mr. YORKE: Oh, that secret.

GROSS: That secret, yes. So how do you think that's affected you as a

songwriter, a singer? Just in terms of like, you know, your subject matter or

your tempos, or, you know...

Mr. YORKE: Yeah.

GROSS: ...the kind of mood you're going for.

Mr. YORKE: I think it's most--both destructive and highly creative. And in

some ways, it's a blessing because when you're in the midst of it, you hear

things and see things in a different way. I mean, actually, some people do

literally see things in a different way. Some people, the things actually do

actually get darker and sounds actually change and blah-blah-blah. And I find

that it's, in a way, it's, you know, my brain is set to receive other things.

And, you know, the trouble with it is, really, that it's debilitating as well,

because you haven't any--you have a problem--you don't have energy. You don't

have--in order to do--especially in a band, actually, but just generally to be

creative, you need to have a lot of energy. You can't just, you know. And so

you can be extremely negative.

But it's really not a big deal, but at the same--I mean, I choose to talk

about it publicly because I've always had a problem with the fact that people

call our music depressing because it's like, `What, you don't get depressed?

What, your whole life is roses, is it?' You know, that's, to me, is like, `You

are in denial and you are the one with the problem.' I mean, I, yeah, I want

to go out. And I listen to disco music, I go, you know, I do this stuff, but

it just so happens that I'm built to do this. This is what I do. I mean,

that's fine. But, you know--and I think that's why I, you know, that was why

I chose to make a thing out of it, because it was just really annoying me.

I know that after, or during, the "OK Computer" tour, which ended up being,

like, a really long tour, and it sounds like you had real trouble toward the

end of it. That it...

Mr. YORKE: There was just a general madness going on, and it started out as

being fun. And then it ceased to be fun and ceased to be relevant to the

music, I think.

GROSS: From what I read, it sounds like there were times onstage during that

tour when you...

Mr. YORKE: Yeah.

GROSS: ...when you were kind of unraveling.

Mr. YORKE: Yeah, that was weird. I mean, I don't know quite why. I think a

lot of the shows were very big and it was not interesting, and mostly it was

just not interesting. It just got boring. Which sounds incredibly selfish,

but why would you just carry on playing these tunes? I mean, you know, the

trouble with it was that by the time we'd done that record, we were so sick of

those tunes. And then you're faced with the prospect of, like, having to play

them for another year and a half which, you know, you've got to do because

you've got to let people know what it's about. And one of the things that

we're good at is playing the tunes and blah-blah-blah. But, you know, there

just sort of comes a point where it's like, this is--you're going through the

motions. And as soon as you realize, `I am going through the motions; this is

sounding tired,' that's it, you know? You--there is kind of no point. This

is--it's rock 'n' roll. There's no point in you being there. It's like, it

ceases to be rock 'n' roll and just becomes some sort of dodgy circus.

GROSS: So did you feel like you were basically forced into the position of

being phony because you were no longer feeling the songs with the same

intensity, and yet you had to play them as if you did?

Mr. YORKE: Well, that was the thing for me. I refused to still stand on the

stage and pretend I was really into it when I wasn't. So I would stand there

on the stage for about half a minute looking out into the audience

going...(sighs)...`I'm not really into this.' Because that was me trying not

to be fake about it.

GROSS: But, of course, that's a real insult to the people who paid a lot of

money to come hear you.

Mr. YORKE: Yeah. Except but it's like, but then, well, what do you want?

Do you want me to be genuine or do you want me to just pretend? Which do you

want, you know? The genuine thing, for me, to do at this point would just to

get on a train and go home.

GROSS: My guest is Thom Yorke of the band Radiohead. We'll talk more after a

break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guest is Thom Yorke of Radiohead. He's the band's main songwriter

and lead singer. This year he came out with a solo CD called "The Eraser."

Well, I want to play another track, and this is from your album "Kid A."

Mr. YORKE: Rah.

GROSS: And I thought we could play "Idioteque."

Mr. YORKE: Hurrah. I like that one.

GROSS: And you got a real, like, electronic thing going on here. When did

you start getting interested in electronic instruments? And I've been really

wondering if you went back and listened to a lot of, like, the early

electronic avant garde music of, say, the '60s?

Mr. YORKE: I did, actually. I mean--the things I was really, really into at

college was electronic music. I was massively into it.

GROSS: Like what kind? Were you...

Mr. YORKE: Well, the Detroit techno stuff that was coming out, and I was

getting--criminy, I don't know what it was, half of it, you know. And there

was all these--there was all this British answer to it, as well as the Warp

label. And they were coming out with just amazing stuff. I mean, the reason

it was amazing was because I was deejaying every Friday at college. And the

stuff that sounded the most exciting coming out of the speakers was not the

rock music. It was this minimal techno. It was just--it just sounded

fantastic coming out of your Technics 1200s that the needle's a bit damaged

and the speakers are kind of blowing up, and you've had a little bit too much

to drink and some twit is asking for the Pogues again. So you just whack on

like some Warp record really loud and just clear the dance floor. But you

were having the best time, and that's--that was my sort of formative thing,

the electronic. It wasn't actually sort of Kraftwerk. And I knew that was

the reference point. And I had "Autobahn," but I didn't know, you know, the

real history behind Kraftwerk at all, you know? I came to it all backwards,

as one does.

And then I got really heavily back into it after "OK Computer," because I'd

absolutely had enough of rock music, predictably enough, you know. I

didn't--I hadn't had enough of being in the band, but I'd had enough of those

sounds. I mean, like, "OK Computer" was a very consciously acoustic record,

using acoustic spaces very, very deliberately, hardly using any fake reverbs,

using real reverbs, and real groove sounds, putting mikes in the wrong ends of

the room and all this sort of stuff.

We'd all read this book on how recording music had changed the way music was

since it was coming out with speakers, and it wasn't live. And the logical

conclusion of this book was electronic music, to me. It was like, you know,

if you put a microphone in front of something, and then you play it out the

speaker, there's all this extra distance between what's really happening and

you. And what was so exciting about electronic music is it's like literally

there's no distance between the music and the speaker. It's just straight out

the speaker. There's no nothing else there at all.

GROSS: Now I could see you being really interested in this and then you could

create this, you know, a electronic environment that you could then sing over.

Mr. YORKE: Yeah.

GROSS: What about the guitarist and the bass player in your band?

Mr. YORKE: Yeah, it was...

GROSS: How did they feel about it?

Mr. YORKE: It was a bit of a brain mash. They were definitely not into it

to begin with. But at the same time, you know, the recordings didn't really

end up like that. I mean, both "Kid A" and "Amnesiac" were lots and lots of

different stuff. There's been a bit of focus on, `Oh, that's when they went

all electronic.' Well, OK, you could say the first song on "Kid A,"

"Everything in Its Right Place," is electronic. But, you know, we'd actually

tried it every other way and it didn't work. And that's how it worked. So

that's that, you know. It wasn't like, `Yes, now we are making electronic

records. You are either with me or you're against me.' It wasn't really like

that.

GROSS: OK. Well, let's hear "Idioteque" from "Kid A." This is Radiohead and

my guest is Thom Yorke.

(Soundbite of "Idioteque" from "Kid A")

Mr. YORKE: (singing)

Who's in a bunker?

Who's in a bunker?

Women and children first

And the children first

And the children

I laugh until my head comes off

I'll swallow till I burst

Until I burst

Until I

Who's in a bunker?

Who's in a bunker?

I have seen too much

You haven't seen enough

You haven't seen it

I'll laugh until my head comes off

Women and children first

And children first

And children

Here I'm allowed

Everything all of the time

Here I'm allowed

Everything all of the time

Ice age coming

Ice age coming

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's Radiohead from their CD "Kid A."

So we were talking a little bit about your kind of electronic or

electronica...

Mr. YORKE: Mm. Mm.

GROSS: ...yeah, influence there.

Mr. YORKE: Yes.

GROSS: And you have a solo CD. It's not Radiohead. It's a Thom Yorke CD and

that's very electronica...

Mr. YORKE: Yes.

GROSS: ...influence. So did you feel freer to head in that direction

without...

Mr. YORKE: I thought I...

GROSS: ...without the other musicians?

Mr. YORKE: Yeah, I wanted to do--doing electronic music is a very--or can be

a very mono experience. It's like you're just sitting there and you're

looking at the computer, blah-blah-blah. I mean it's not fun for a group of

musicians to sit in a room and watch a screen. It's not very interesting,

really. And if you work--well, I mean, in this case, it was very much a

collaboration between me and Nigel. But when you're just sort of sitting

there and there's only two of you, there was very little discussion going on.

You're just doing it which, you know, when it's electronic music, seems to

make quite a lot of sense, really.

I mean, even that's, I mean, that's the case when we were doing "Kid A," as

well. You know, a lot of the stuff on that was just, well, there'd be one or

two people involved. And it's just in this particular instance we were taking

a break and said, `I really wanted to just go off and try doing something on

my own. Just, I want to know what it feels like,' you know. I mean, that

doesn't mean we're never going to do that stuff again either.

And in fact, I think one of the interesting things about it was just how, you

know, you have to work on intuition. And it was done very quickly and very

fast, and you get your sense of instinct sort of back on things, and I feel

that will feed well into working with a band. Well, it is doing already,

really.

GROSS: Well, Thom Yorke, thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. YORKE: Thanks, Terry. That was cool.

GROSS: Thom Yorke is the main songwriter and lead singer of the band

Radiohead. I spoke with him in July. This year he released a solo CD called

"The Eraser." Here's track from it called "Atoms for Peace." I'm Terry Gross

and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of "Atoms for Peace")

Mr. YORKE: (singing)

No more going down the dark side

With your flying saucer eyes

No more falling down a wormhole

That I have to pull you out

The wriggling twiggling worm inside

Devours from the inside out

(End of soundbite)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Stuart Murdoch talks about his band Belle & Sebastian's

early career, his bout with CFS, and his major influences

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Since the band Belle & Sebastian formed

10 years ago in Glasgow, Scotland, they've developed a cult following. A

Washington Post review described the band's latest CD, "The Life Pursuit," as

a terrific pop album. In a review of that CD in the online music magazine

Pitchfork, Marc Hogan wrote, "Spanning glam, soul, country and 70s AM rock,

this record is a deceptively wry, wickedly tuneful testament to the fragile

beauty of faith in deities as well as in pop."

My guest is the co-founder of Belle & Sebastion, Stuart Murdoch. He sings and

writes most of the songs. When the band started out, he declined to speak to

the press. But that changed a few years ago. Here's a track from "The Life

Pursuit" called "Another Sunny Day."

(Soundbite of "Another Sunny Day")

Mr. STUART MURDOCH: (Singing) Another sunny day

I met you up in the garden

You were digging plants

I dug you, beg your pardon

I took a photograph of you

in the herbaceous border

It broke the heart of men and

Flowers and girls and trees

Another rainy day

We're trapped inside with a train set.

Chocolate on the boil

Steamy windows when we met.

You've got the attic window

Looking out on the cathedral.

And on a Sunday evening

Bells ring out in the dusk.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: I spoke to Stuart Murdoch earlier this year when Belle & Sebastian

were on tour in the US. I asked him how he started writing songs.

Mr. MURDOCH: Well, to be quite honest, I had a busy period when I was

younger. I was at college and I was deejaying, and I was working as a roadie

and working in a record shop. And then I actually got unwell, and I had to

give up all these pursuits one by one over a period of time, and then for

quite a few years, in fact, for seven years, I was pretty much out of the

game. And it was during this period that I found a lot of solace in being

able to write a song.

GROSS: So I had read a reference to CFS, chronic fatigue syndrome. Is that

what you have?

Mr. MURDOCH: Yes, pretty much. It was all sorts of post-viral difficulties.

It was a major drag, as you can imagine.

GROSS: Well, it must have been really awful to go from having this life where

you're, you know, you are a deejay in clubs and, you know, living this really

interesting life, going to all the record stores, and then you're, like, stuck

at home. Did you move back home with your parents?

Mr. MURDOCH: Yes, I had to--I moved back in with folks, and they put up with

me, and pretty much I shed--like you said, I shed everything, all my friends

and activities, not because I wanted to but simply because I had to.

GROSS: Boy, it must be hard to start something new and difficult, like

writing songs when you're sick.

Mr. MURDOCH: It was, but--well, it was, but it felt like the one major thing

that I had. When I started to do it, I realized that this could be a way out,

and this could almost make up for what was happening to me.

GROSS: Well, I'd like to play a song that you wrote that's on the first CD,

the first Belle & Sebastian CD, "Tigermilk," and of course, I don't really

know which songs you wrote because you don't include songwriter credits on the

CDs. Why not?

Mr. MURDOCH: I'm not really sure. It just, at the time, it just seemed

unimportant.

GROSS: Well, did you write "Expectations"?

Mr. MURDOCH: Yes.

GROSS: Good. That's the one I was going to play.

Mr. MURDOCH: Good.

GROSS: So we'll listen to that. Do you want to say anything about writing

the song? I mean, it's a story song, it's a character song. And--I mean, I

think of you in the song carrying on the tradition of, say, Ray Davies from

the Kinks and Randy Newman. Of, you know, it's not a confessional song.

Mr. MURDOCH: Yeah.

GROSS: It is not about you.

Mr. MURDOCH: Yeah.

GROSS: It's about a character.

Mr. MURDOCH: That's right. I had great fun with these characters,

especially painting a character, someone who I would have felt was pretty hip

at the time, and you sort of bring them to life in your imagination.

GROSS: So you thought they were pretty hip at the time you were writing this

song?

Mr. MURDOCH: I think so, yeah.

GROSS: So this is about somebody who makes life-size models of the Velvet

Underground in clay.

Mr. MURDOCH: I mean, wouldn't that be fantastic? I mean, this is--because I

imagined back to being, you know, much younger and that time, you love it when

you are looking up towards the people in your class or in your school that are

obviously way cooler than you, and you're wondering how--you're wondering what

goes on in their mind. And I just imagined this figure who was, you know,

modeling the Velvet Underground and had this project and this obsession, and I

didn't even know who the Velvet Underground were.

GROSS: OK. Well, let's hear it. This is from the first Belle & Sebastian

album, "Tigermilk." And this is "Expectations."

(Soundbite of "Expectations")

Mr. MURDOCH: (Singing) Monday morning wake up

Knowing that you've got to go to school

Tell your mum what to expect

She says it's right out of the blue

Do you want to work in Debenham's

Because that's what they expect

Start in Lingerie

And Doris is your supervisor

And the head said that

You always were a queer one

From the start

For careers you say you want to be

Remembered for your art

Your obsession get you known

Throughout the school

For being strange

Making life-size models

Of the Velvet Underground in clay.

In the queue for lunch, they take the piss

You've got no appetite

And the rumour is

You never go with boys

And you are tight.

So they jab you with a fork,

You drop the tray and go berserk

While you're cleaning up the mess,

The teacher's looking up your skirt

Hey, you've been used

Are you calm?

Settle down,

Write a song, I'll sing along.

Soon you will know that you are sane.

You're on top of the world again.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's Belle & Sebastian. The song "Expectations" that we just heard

was on their first album, "Tigermilk." It was written and sung by my guest

Stuart Murdoch.

This seems to be really influenced by the group Love.

Mr. MURDOCH: This is one of the groups, along with perhaps an American group

called the Left Bank and, also, a group called The Loving Spoonful...

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. MURDOCH: ...and the English group, the Zombies. Now there's four groups

that our group all revered.

GROSS: Mm-hmm. I can see why.

Mr. MURDOCH: Yeah. Perfect.

GROSS: Now, so here this is your first album and you have. like, strings on

it. There's a trumpet. Did you have friends who could play those instruments

in a rock setting, in a pop setting?

Mr. MURDOCH: Well, I didn't know I had friends until--well, I quite honestly

didn't know these people. They became my friends. But the story of the first

LP was that I had been trying to find these people for so long...

GROSS: People that you could make music with and felt connected to?

Mr. MURDOCH: Absolutely. And during, you know, point in my--you know, when

I wasn't feeling so good, and then, all of a sudden, in this one period of

time, and it was when I was just about to leave Scotland to actually move to

California to try my luck there, that I was asked to produce the "Tigermilk"

LP for a local college. And it was at that point that I met the people that

worked to make the record.

GROSS: Now, doesn't this record have something to do with some kind of

competition?

Mr. MURDOCH: That's right. The college in Glasgow, Stow College, every

year, they sponsored a group or an artist to make a record. And so this year,

they somehow got ahold of a demo tape of mine, and they asked me to make the

record. I think that was the inspiration for what seemed to be the thing that

brought these musicians together rather quickly. It was very fateful.

GROSS: So getting back to the idea that there's strings, trumpet on this CD,

did you hear those sounds in your head? I mean, when you wrote the song, did

you say, `This needs a violin and a trumpet. And this is what they need to be

playing'? Did you hear the song that way in your mind?

Mr. MURDOCH: Yes. Absolutely. That was--if there was one thing about the

sound of, you know, fledgling Belle & Sebastian that I wanted, it was that the

trumpet should be as important as the guitar, that the cello should be as

important as the piano and etc. And that I should form a small compact

baroque unit that would be able to, yeah, play great pop lines.

GROSS: My guest is Stuart Murdoch, the lead singer and songwriter of the band

Belle & Sebastian. Their latest CD is called "The Life Pursuit." More after a

break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guest is Stuart Murdoch, the lead singer and songwriter of the band

Belle & Sebastian.

So when you were getting started and you're a band from Glasgow, did it help

to be--in Glasgow itself, did it help to be a local band? Or was that held

against you?

Mr. MURDOCH: Well, we didn't really care about what anybody else thought.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. MURDOCH: We definitely felt as a group that we were deeply

unfashionable. The sort of people that came together for the group were

misfits. We weren't hip at all, in my book. I think that helped, in a way,

because we banded together, and we didn't want anything to do with any of the

other groups around at that time.

GROSS: What made you feel unhip?

Mr. MURDOCH: Probably just healthy paranoia. I can remember getting up in

parties and, you know--I cringe when I think of it now--and almost forcing

people to listen to songs that I'd written playing acoustically. And I can

remember people probably talking up their sleeves thinking, `Oh, I wish this

guy would shut up. I wish this guy would go away.'

There was a distinct feeling in the Glasgow of this period that all the great

music had been done, so why bother? You know, all these great records from

the '60s had been made, so, you know, it was impertinent even to try and write

another song. This fueled me deeply--this made me want to make the most

terrific records that I could imagine.

GROSS: Well, the same year that you released your first album, "Tigermilk,"

1996, you also released an album that--well, yeah, it came out the same year.

And I want to play something from that album. It's called "If You're Feeling

Sinister." And the track I want to play--did you write "Judy and the Dream of

Horses"?

Mr. MURDOCH: Yes. I wrote pretty much all the early stuff. Yes. Yes, I

wrote "Judy."

GROSS: OK. Good. Good. This is a great song, and one of the things I find

interesting about it as a record is that it starts out sounding almost alost

like it's going to be like Gilberto or Jobim, bossa nova, and then it--the

mood changes, and then, you know, the trumpet comes in, and so--I, when I

listen to your music, I just hear all these interesting, different influences

coming together to create your song. Were you interested in bossa nova?

Mr. MURDOCH: Not really. I was more interested in the--in perhaps the

second half of it when it explodes into bubble gum pop. Perhaps it still

sounds a bit folky, that record. I think we could have a better go at it now.

I mean, we were quite naive in our early days of production. But I always

heard "Judy" as being a bit of bubble gum pop.

GROSS: Let's hear it. This is "Judy and the Dream of Horses" from the Belle

& Sebastian CD, "If You're Feeling Sinister."

(Soundbite of "Judy and the Dream of Horses")

Mr. MURDOCH: (Singing) Judy, let's go for a walk

We can kiss and do whatever you want

But you will be disappointed

You will fall asleep with ants in your pants

Judy, you're just trying to find

And keep the dream of horses

And the song she wrote

Was "Judy and the Dream of Horses"

Dream of Horses.

Dream of Horses.

Dream of Horses.

The best-looking boys are taken

The best-looking girls are staying inside

So, Judy, where does that leave you?

Walking the street from morning to night

With a star upon your shoulder

Lighting up the path that you walk,

With a parrot on your shoulder

Saying everything when you talk

If you're ever feeling blue

then write another song

about your dream of horses.

Write a song about your dream of horses.

Call it "Judy and the Dream of Horses."

Call it "Judy and the Dream of Horses."

Your dream of horses.

Da-da-da

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's "Judy and the Dream of Horses" from the Belle & Sebastian CD,

"If You're Feeling Sinister" from 1996. My guest Stuart Murdoch sang it and

wrote the song. And--and they have a new CD, which is called "The Life

Pursuit."

Now before we heard this track, you said that you were really thinking of

bubble gum pop. When you think bubble gum, who do you think of?

Mr. MURDOCH: Oh, I'm just thinking of something like "Sugar, Sugar" by the

Archies...

GROSS: Yeah. OK.

Mr. MURDOCH: ...which is basically--I mean, that's my taste. That's the

kind of song I just love. I love just turing on the radio, hearing classic

hits from the '60s and '70s.

GROSS: I am interested in how songs come to you. You know, again, you didn't

start writing songs until you were what, in your early 20s? Would that be it,

about?

Mr. MURDOCH: Probably about right, 24 even.

GROSS: Uh-huh. Uh-huh. Which is kind of old in a way. Like a lot of people

who write songs are writing songs in their teens, and there is always original

music going through their head. When you decided you wanted to write songs,

was it an act of will that you, like, sat down and thought, `I'm going to

write a song.' And did you just like consciously craft it, or was there just

like music coming to you in your head?

Mr. MURDOCH: Yes, well, I would say it certainly wasn't an act of will, and

what came to me at first was a desperation to communicate in some way or form.

And it was really through--it was really through words. And it was almost

just by accident that I learned that instead of simply writing bad poetry that

you could write bad poetry with a melody attached and then you could get away

with it.

GROSS: Did you write poetry when you were in high school or college?

Mr. MURDOCH: Well, no. Not really. Not really. It just--the urge just

came to me a few years after I'd gotten sick. But I mean, in a sense, pop

music is bad poetry with a, you know, with a sweetener, and so this is what I

found out. I sat down at the piano, and I formed my first bad poem with a

melody, and I never looked back.

GROSS: My guest is Stuart Murdoch, the lead singer and songwriter of the band

Belle & Sebastian. Their latest CD is called "The Life Pursuit."

More after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

(Soundbite of Belle & Sebastian)

Mr. MURDOCH: (Singing) Something you think of the way you're feeling

Because...(unintelligible)

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: My guest is Stuart Murdoch, the lead singer and songwriter of the band

Belle & Sebastian.

You used to live above a church, and you were the church's caretaker. You did

this for how many years?

Mr. MURDOCH: Maybe about seven or eight years.

GROSS: Mm-hmm. And this was--place this for us chronologically, this was

after you had recovered from the chronic fatigue? Were you already recording?

Mr. MURDOCH: This was precisely at the time that the group came together. I

guess I'd been, you know, living from, sort of, room to room around Glasgow

and just, you know, getting on with my sort of gloomy existence up to a point.

And then I attended the church, and the minister knew that I didn't really

have a permanent place to stay, and he offered that I should stay in the

church building, the church hall, and look after the premise and, you know,

and not pay rent. So it was a nice arrangement where I did this job, and I

lived there for free--and this was at exactly the same time that the group

came together at January 1996, which was a couple of months before "Tigermilk"

was recorded.

GROSS: So what was it like to live above a church? I mean, did you feel the

specialness of the--you know, like, some churches in particular have a

very--either spiritual or at least beautiful and, in some situations, ancient

or old feeling about them. I don't know what kind of church this was, whether

this was a little corner church or, you know, a beautiful and very old church.

Mr. MURDOCH: Yes, well, there was a mixture of that. There was the main

church building which was just 100 yards up the street. And this was the

smaller building where all the clubs and societies used to meet, and they had

sort of social gatherings in the hall. And so it was busy all the time with

the groups, with the old ladies coming in to drink their coffee in the morning

or the mothers and toddlers coming in in the afternoon. And there would be

bridge clubs and choirs and drama clubs and cubs and scouts. And so it was

busy. It was social. And I must admit, I liked it, and I--and there was a

special atmosphere and--from the place--and I didn't take that for granted. I

used to--you know, when I was cleaning up at night and everybody had gone and

the huge hall had a special atmosphere with the streetlight coming in, and I

loved that.

GROSS: Well, I thought I'd play a song that I'm assuming you wrote, and you

can tell me if you did. It's called "If You Find Yourself Caught in Love."

And, you know, it's a song that certainly acknowledges religion. Did you

write this one?

Mr. MURDOCH: Yes, I did. Uh-huh.

GROSS: Do you want to talk about this song a little bit?

Mr. MURDOCH: Yes. It is a bit of a funny one, because it does almost--it

has a certain gospel sort of hint to it. And it's something, at the time when

I was writing, I thought, `Well, should I be so overt?' Because I've often

sort of couched any religious overtones, you know, within characters or

something like that in the past. But this is a bit more out there, and then I

just thought, `Come on. We've been doing this for years. Why not? You know,

why not just a bit more straightforward?'

GROSS: Was it hard to figure out a way to get some acknowledgment of God in a

song without it sounding like Christian rock?

Mr. MURDOCH: Yes. It's a fine line, isn't it? I mean, I don't mean to be

down on Christian rock, but it's not my cup of tea. So, I guess you just got

to do what you feel, all the time be, you know, be led by taste. Just you

have to do what you like.

GROSS: OK. So this is from the Belle & Sebastian CD "Dear Catastrophe

Waitress." The song is "If You Find Yourself Caught in Love, Say a Prayer to

the Man Above."

(Soundbite of "If You Find Yourself Caught in Love")

Mr. MURDOCH: (Singing) If you find yourself caught in love,

Say a prayer to the man above

Thank Him for everything you know

You should thank Him for

every breath you blow.

If you find yourself caught in love,

Say a prayer to the man above

Thank him for every day you pass

You should thank him for

Saving your sorry ass

If you're single but looking out

You must raise your prayer to a shout

Another partner must be found

Someone to take your life beyond

Another TV "I "Love 1999"

Just one more box of cheapo wine

If you find yourself caught in love

Say a prayer to the man above

But if you don't

Listen to the voices

Then, my friend

You'll soon run out of choices.

What a pity it would be!

You talk of freedom,

Don't you see.

The only freedom that

You'll ever really know

Is written in books from long ago.

Give up your will to Him that loves you,

Things will change--I'm not saying overnight.

You've got to start somewhere

Shed a tear for the one you love

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's "If You Find Yourself Caught in Love" from the Belle &

Sebastian CD "Dear Catastrophe Waitress." My guest Stuart Murdoch wrote and

sung that song, and they have a new CD now.

So let's try to bring ourselves up to date a little bit. You're no longer

living above the church. Do you live in Glasgow?

Mr. MURDOCH: Nope. Yes, I actually just moved out of the church last year.

GROSS: Last year, wow! Cool. What was it like when fans--I mean, fans must

have known you lived there. So--and it's certainly got to be an easy place to

find.

Mr. MURDOCH: Yes. It was. I think our fans have always been very

respectful...

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. MURDOCH: ...of the group, so that's been nice from the start. And

whenever we have, you know, run-ins with fans, or whenever the fans have come

to the church, which has happened quite regularly, they get a little bit more

than they bargained for. Because perhaps they--they want to creep in and sit

quietly in one of the pews at the back and may be spot me from afar or

whatever. But they get pounced on by the congregation, by the ladies in the

church. And they have to come and drink tea and sign the visitor's book and

explain where they're from. So they're made welcome.

GROSS: Well, Stuart Murdoch, thank you very much for talking with us.

Mr. MURDOCH: It's been a pleasure.

GROSS: Stuart Murdoch is the lead singer and songwriter of the band Belle &

Sebastian. I spoke with him in March. Belle & Sebastian's latest CD is

called "The Life Pursuit."

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

(Soundbite of "Funny Little Frog")

Mr. MURDOCH: (Singing) Honey, loving you is the greatest thing

I get to be myself and I get to sing

I get to play at being irresponsible

I come home late at night and love your soul

I never forget you in my prayers

I never had a bad thing to report

You're my picture on the wall

You're my vision in the hall

You're the one I'm talking to

When I get in from my work.

You are my girl, and you don't even know it

I am living out the life of a poet

I am the jester in the ancient court

And you're the funny little frog in my throat

My eyesight's fading, my hearing's dim

I can't get insured for the state I'm in

(End of soundbite)

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.