Other segments from the episode on October 21, 2005

Transcript

DATE October 21, 2005 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Comic and actor George Carlin

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

My guest is comic and actor George Carlin. He has a new HBO comedy special

that debuts November 5th. Carlin's best-selling book, "When Will Jesus Bring

the Pork Chops?," has just come out in paperback. The book takes aim at two

of Carlin's favorite targets, euphemistic language and political correctness.

Carlin's most famous comedy monologue has become known as `seven words you can

never say on television.'

In 1973 the Pacifica radio station in New York, WBAI, played this monologue

without bleeping those seven words. After a complaint was filed, the FCC put

WBAI on notice, threatening possible sanctions against the station if

subsequent complaints were received. WBAI appealed the decision. The case

eventually made it to the Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of the FCC, and

enabled the FCC to regulate the broadcast of indecent content.

The decision became particularly relevant when the FCC tightened standards

following Janet Jackson's `wardrobe malfunction.' Here's a 1972 recording of

Carlin's monologue. We have, of course, bleeped the words that made this

routine famous.

(Excerpt from Carlin monologue)

Mr. GEORGE CARLIN (Comic/Actor): There are 400,000 words in the English

language, and there are seven of them you can't say on television. What a

ratio that is. Three hundred and ninety-nine thousand, nine hundred and

ninety-three to seven. They must really be bad. They'd have to be outrageous

to be separated from a group that large. All of you over here, you seven, bad

words. That's what they told us they were, remember? `That's a bad word.'

No bad words. Bad thoughts, bad intentions and words. You know the seven,

don't you, that you can't say on television? (Expletives deleted)

(Soundbite of applause)

Mr. CARLIN: Those are the heavy seven. Those are the ones that'll infect

your soul, curve your spine and keep the country from winning the war.

GROSS: George Carlin, welcome to FRESH AIR.

Mr. CARLIN: Thanks, Terry.

GROSS: Can you talk about what led to this routine, like what you were

thinking about, how you wrote it?

Mr. CARLIN: Well, what happened was I'd always held these attitudes, I've

always been sort of anti-authoritarian and I really don't like arbitrary rules

and regulations that are essentially designed to get people in the habit of

conforming. And I have always taken great joy in looking more closely at

language.

On these other things, we get into the field of hypocrisy, where you really

cannot pin down what these rules they want to enforce are. It's just

impossible to say, `This is a blanket rule.' You'll see some newspapers print

F-blank-blank-K. Some print F-asterisk-asterisk-K. Some put `expletive

deleted.' So there's no real consistent standard. It's not a science. And

it's superstitious. These words have no power. We give them this power.

It's the rest of the sentence that makes them either good or bad.

GROSS: In your 1972 recording, you talk about how it's perfectly OK to say,

`Don't prick your finger,' but you can't say, `Don't finger your blank.'

Mr. CARLIN: Yeah, you can't reverse the two.

GROSS: You can't reverse the two words. So comics work with the power of

words. And, in a way, the fact that certain words are supposed to be taboo,

as you point out, that gives them power.

Mr. CARLIN: Yes. That's right.

GROSS: And that makes those words more powerful for you when you want to use

them. So do you feel like you've been able to work with the taboo nature of

certain words and, you know, make that work in your favor?

Mr. CARLIN: Well, what...

GROSS: Like in that classic routine?

Mr. CARLIN: Yeah. That is an interestingly disguised way--and I don't mean

you were trying to deceive me or anything--but it's a disguised way of saying,

`Well, don't some people just use these for shock value?' You get this phrase

all the time from interviewers, `shock value.' Well, shock is a kind of a

heightened form of surprise, and surprise is at the heart of comedy. So if

you're using the word in a way to heighten the impact of the sentence or

season the stew, they are, after all, great seasonings. There are sentences

that, without the use of `hell' or `damn' even, lose all their impact.

So they have a proper place in language. And in my case, I just like them

because they are real and they do have impact. They do make a difference in a

sentence. But if you're using them for their own sake, that's probably kind

of weak.

GROSS: Did you ever expect that that comedy routine would be actually played

on the radio, that it would be part of a case that made it all the way to the

Supreme Court and that it would become as important and famous a case as it

became?

Mr. CARLIN: Well, I knew that it wasn't out of the question that it may be

played on the radio. FM radio stations at that time--and there were

commercial ones who qualified as what was called underground radio. And an

awful lot of liberties were taken with music, too, music that had very--I

don't--God, I hate the words `explicit' and `graphic' but those are the words

that would be used by someone to describe those kinds of songs, those lyrics.

I knew there was a chance, but, of course, you know, no one ever sees other

things coming that are unexpected and larger, you know. I just knew that I

had done a piece that summed up my position very well and sort of had a

nice--it had a wonderfully rhythmic--the reading of those seven words, the way

they were placed together had a magnificent kind of a jazz feeling, a rhythm

that was just very natural and satisfying, the way those syllables were placed

together. And so I knew I had done something that was making an important

point about the hypocrisy of all of this.

GROSS: Were you at the Supreme Court when the case was being argued?

Mr. CARLIN: No. No, I was an interested bystander. It wasn't my case. It

generated a certain amount of attention for me which, I guess, a performer

never walks away from, but I decided very early not to try to either exploit

the incident and the episode or to walk away from it and disavow it. I just

let it be as it was happening and let the results of it land wherever they

would.

*********

GROSS: Does this surprise you still when you hear, say, the language that's

used on "The Sopranos" or other HBO shows? You know, that it--you know,

because it's the language that you could never say on broadcasting...

Mr. CARLIN: Yes.

GROSS: ...and that you still can't say on broadcasting, you can say on cable

and now you can say it on satellite radio, which is where...

Mr. CARLIN: Yes.

GROSS: ...Howard Stern is moving, where "Opie & Anthony" have already moved.

So I mean, there are two different sets of standards, but does it surprise you

to hear language coming from your television like that?

The interesting thing about it for me is this is how people talk, not

everyone, of course, but a significant number of people use these words all

the time. And when I was a little boy, I was told to look up to--because it

was just--there was the Second World War; I was born in 1937. I was taught to

look up to soldiers and sailors--that's the only words you really used for the

armed forces--soldiers and sailors, policemen, of course, and athletes. That

was to develop a little more later. But these are the people you should model

yourself after. These are the paragons of American value and virtue.

Well, we all know how they talk. We all know how those three groups talk, the

military, the athletes and the police. And that--to hear police shows all

these years and war movies all these years without the sort of language they

were using immediately branded them as inauthentic to me. I could get past it

and suspend my disbelief from time to time with compelling writing or scenes

or something, but largely I thought, `That's not what he would say. That's

not what he would la--I think he would say it like this.' So it's just

inauthentic. It's a counterfeit representation of real life that these

commercial and religious interests impose or try to impose on people.

GROSS: Do you remember how you were first exposed to four-letter words and

what your reaction was when you first were?

Mr. CARLIN: Well, I was--I grew up in part of New York City that's a very

interesting neighborhood. I lived--literally my front door was across the

street--and I mean literally in its real sense here--literally across the

street from Teachers College of Columbia University. And all around me to the

south I had Columbia University Teachers College, Barnard College; Juilliard

School of Music was around the corner, the original location. Riverside

Church, the 23-story interdenominational cathedral, the Gothic cathedral, was

at the end of my street; Union Theological Seminary, the largest seminary in

the world, and around the corner The Jewish Theological Seminary, the largest

Jewish seminary in the world. St. John the Divine was nearby, and Grant's

Tomb. So it was highly institutional neighborhood full of learning and

serious people.

Immediately to the north down the hill we had the beginnings of Harlem. We

called our section White Harlem because we thought it sounded tough. There

were cross-pollination between these two groups. I lived very close by

Cubans, Puerto Ricans and Dominicans on the one hand, and blacks on the other.

And when you're in those neighborhoods at the border, betw--my arts was a

little Irish enclave, just a little wedge-shaped Irish enclave in the middle

of all that, highly populated because we were quite fertile folks. Lot of

kids, lot of kids on the street. And when you live near the border between

all-black and all-white, you don't have the attitudes that the people who are

insulated and isolated in the center of those areas have. Those are people

who are not in contact day to day to day with the opposite. But we did have

contact all the time, and when you're on the border between two cultures, you

sort of learn to live together. You have a common code of the streets, in

this case. And so I heard my language from the realistic people in the

neighborhood, my big brother, for one. But that's where I got a realistic

feeling and look at the world.

GROSS: Did language get you into trouble as a kid?

Mr. CARLIN: Well, I--because I liked language--as I was saying, my

grandfather wrote out all of the works of Shakespeare in his adult life

longhand because of the joy it gave him--those were his words. But I then

started collecting exotic combinations of curses that I heard in my

neighborhood. I was probably 13 or 14 at the time. And there were guys who

would put together a sentence in the heat of anger or in some ornate,

descriptive passage in something they were describing, and they would have an

adjective or two, self-hyphenated. They would have made up a form and tacked

it onto some noun that it didn't really go with, and the rest of the sentence

might have been some colorful verb that was, again, very inventive street

language. And some of them were very colorful and exotic and different. They

weren't just flat-out curses.

So I heard these and then I started writing them down. In another situation

where I could tell you what they were, you'd understand a little better even

what I mean. But I wrote them down and I had a little list of them--I had

about 10 or 12 of them. There are a few I can still remember. But I've had

that in my wallet, and my mother was a snoop and discovered things I had

stolen that way and confronted me with them. But in this case, looking in my

wallet, she found this list. And I heard her--I came in one night and I

opened the door very slightly in the apartment on the second floor, and I

heard her talking to my Uncle John(ph), and she was worried about me anyway

because I was kind of a--I was getting to be a loose cannon kind of an

adolescent, and I heard her saying, `I think he may need a psychiatrist, John.

I think we may have to get a child psychiatrist for him,' because she was

telling him these words and showing him this list. So yeah, they got me in

trouble that way, but at least it was a creative effort.

GROSS: Although your mother was appalled finding this list...

Mr. CARLIN: Yeah.

GROSS: ...of street words in your wallet, you earlier credited your mother

with having...

Mr. CARLIN: Oh, yes, she was...

GROSS: ...a love of language and helping to instill it in you.

Mr. CARLIN: Yeah.

GROSS: How did her love of language express itself?

Mr. CARLIN: She was wonderful, and she was my hero. She brought up two boys

in the Second World War on an advertising job she had, and had no father

present in the home, and she stimulated that thing in me about language--she

would send me to the dictionary. I mean, that was pro forma in a lot of

families--I know that's what you do. But she would say, `Get the dictionary.'

I asked her once what `peruse' meant. I said, `Ma, what's "peruse"?' She

said, `Well, get the dictionary in here. Let's get the dictionary.' So I'd

look it up and she'd have me use it in a sentence of my own, and we'd talk

about the root or the origin of it and which definition was more useful and

current and so forth. And so the next day when I gave her her newspaper in

the evening--it wasn't a nightly custom, but sometimes I went and bought her a

newspaper when she'd come home from work--I brought it in her bedroom and gave

her the newspaper and I said, `Here, Ma,' I said, `Would you like to peruse

this?' And she said, `Well, maybe I'll give a cursory glance.' And it was

right back to the dictionary.

GROSS: My guest is comic George Carlin. His best-selling, "When Will Jesus

Bring the Pork Chops" has just come out in paperback, and his 13th HBO

comedy special debuts November 5th. Our interview was recorded last November.

This is FRESH AIR.

Whew! Well, we got through that interview without saying anything that would

get us into trouble with the FCC, but it's great to talk with people like

George Carlin who provoke you and get you thinking while they get you

laughing.

(Fund raiser)

GROSS: let's get back to our interview with comic George Carlin.

Now I know you made it onto radio before you became...

Mr. CARLIN: Yes.

GROSS: ...famous as a comic. What was your radio persona?

Mr. CARLIN: Well, I was on a--the first job I had was in a

place--Shreveport, Louisiana, which sounds like kind of an easily ignored

place, but it had nine stations. It was a hot radio market, as they said, and

we were number one. I had a 52 share. So it was Top 40, but it wasn't as

rigid as Top 40 became. It wasn't as--it didn't sound, you know, like a

robot--time, temperature and the label and the name of the artist. You could

be a little bit of a personality, too. So we played Top 40, and I was, you

know, a very--I was only 18. It was great to be playing the very music that I

was dancing to at night. I mean, it was nice to go over to a girl in a

situation like at a bar or something and say, `Would you like me to play a

song on the radio for you tomorrow and dedicate it to you?'

GROSS: (Laughs)

Mr. CARLIN: It was a little underhanded, but it sure worked a lot.

GROSS: Works like a charm.

Mr. CARLIN: Yeah.

GROSS: And would you talk your way through the instrumental up to the vocal

of the record?

Mr. CARLIN: Some of the time, sure. Yeah, you use--you know, the first

eight bars or 16 bars or whatever the instrumental intro was, you bring it up

first for about three or four seconds, then you bring it down. You say, `OK,

the new Connie Francis just came in.' And I'm exaggerating my disc jockey

voice. `And here at 15 minutes past 5 on "The George Carlin Show" on KJEL,

we're going to listen to this brand-new one,' and then (makes sound) up with

the vocal, you know?

GROSS: (Laughs)

Mr. CARLIN: I loved running a tight board. We ran our own boards, and I

loved it. I was so proud of tight cues and segues that were tight, you know.

It was just a point of pride.

GROSS: Who were the first comics that you heard where you thought, `They

nailed it. This is what life is about'? Like, they just described life.

Mr. CARLIN: Yeah. Of course, comedy changed in the 1950s when the

individuals emerged, and nobody was all the same anymore. It used to be very

sane, very safe and very same. And then Lenny Bruce, Mort Sahl, Nichols & May

and a lot of other people in the improv groups and some underground press and

so forth took hold of comedy and changed it. And so it was that crop in the

'50s--I was then approaching my 20th birthday. And Lenny Bruce was, of

course, the most--the one who inspired me the most because I saw for the very

first time utter and complete honesty on a stage. And it really did help me

later to decide to be myself.

GROSS: How much do you think your comedy has changed from when you first

started doing stand-up?

Mr. CARLIN: Well, I began in 1960. I went through about eight or nine years

of what essentially were the extended 1950s, sort of a button-down period.

But that was when the country was changing. I was 30 in 1957. The people I

was entertaining were in their 40s, and they were the parents of the people

who were 20, 18, in college, beginning to change the nature of our society to

a great extent. So I sided more with them because I was anti-authority, and I

just let myself revert to my deferred adolescence and be one of them in terms

of my work rather than these people I really disliked, who I was entertaining,

these 40-year-old-plus people.

GROSS: Were you performing to older audiences because those were the people

who could buy the tickets in the places that you were performing?

Mr. CARLIN: Well, no, not strictly speaking. I had always been this

lawbreaker, outlaw-type kid and adolescent and Air Force guy, as you pointed

out; never stuck by the rules, always swimming against the tide. But I had a

mainstream dream, and my dream was to be like Danny Kaye in the movies...

GROSS: (Laughs)

Mr. CARLIN: ...or to be like Bob Hope in the movies. So I never put those

two things together. I never saw that they didn't go together. And I

followed this other dream in the way that you did because the only way you

could do it was to please people with mainstream, safe comedy kits, what the

period demanded and got. So I did that until the two became--it became an

untenable situation. I could no longer be myself inside and serve these other

things. And when I saw the mix, when I saw the mistake, I went about

correcting it in a slow and orderly manner. It took about two or three years

for my changes, as it were, to take place.

GROSS: Well, George Carlin, I'd like to ask you to end our interview by

reading the final piece in your new book.

Mr. CARLIN: Oh, sure. OK.

GROSS: And the book is called "When Will Jesus Bring the Pork Chops?" And

this piece is called "The Secret News."(ph)

Mr. CARLIN: I have a big file called News, and it has a lot of odd news

formats. And one of them was this one called "The Secret News." And this was

actually written and designed to be on an album, maybe, a studio-type album,

where you could use sound effects and you were simulating actual broadcasting.

But it works this way, too. It's called "The Secret News," and we hear a news

ticker sound effect.

(Soundbite of Carlin making news ticker effect)

Mr. CARLIN: And the announcer whispering, saying, `Good evening, ladies and

gentlemen. It's time for "The Secret News." And the news ticker gets louder,

and he goes, `Shhh.' And the ticker lowers. `Here's the secret news. All

people are afraid. No one knows what they're doing. Everything is getting

worse. Some people deserve to die. Your money is worthless. No one is

properly dressed. At least one of your children will disappoint you. The

system is rigged. Your house will never be completely clean. All teachers

are incompetent. There are people who really dislike you. Nothing is as good

as it seems. Things don't last. No one is paying attention. The country is

dying. God doesn't care. Shhh.'

GROSS: George Carlin, thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. CARLIN: Sure. Thank you. I always appreciate--I'm not flattering

here--an intelligent interview, and I thank you for that.

GROSS: George Carlin's new book, "When Will Jesus Bring the Pork Chops?", has

just come out in paperback. His 13th HBO comedy special debuts November 5th.

Our interview was recorded last November.

I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

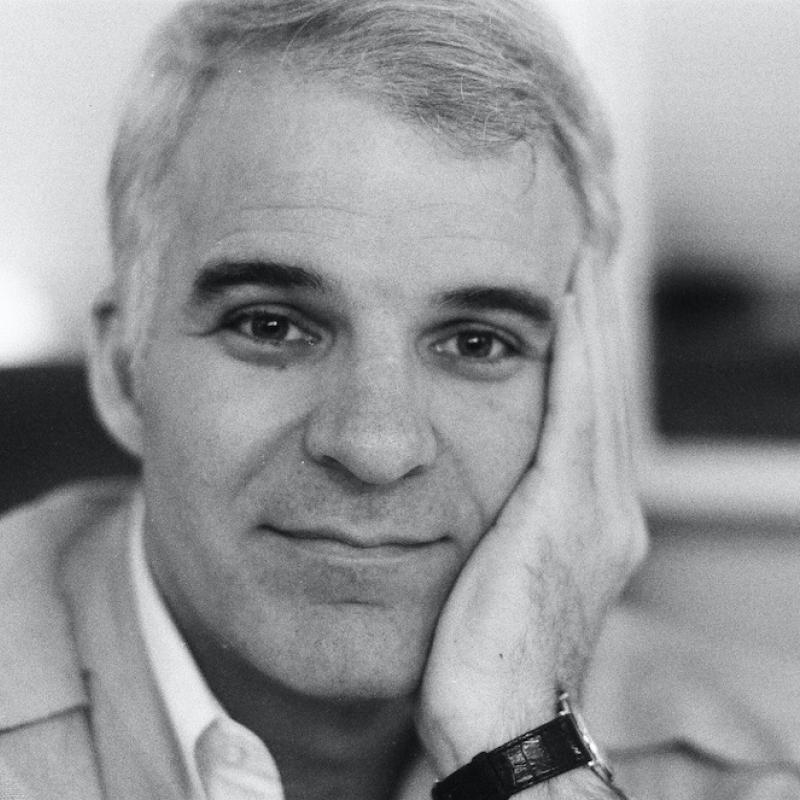

Interview: Steve Martin on his new book "The Pleasure of My

Company"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

My guest is the great actor and comic Steve Martin, the star of such films as

"The Jerk," "All of Me," "Roxanne," "Dirty Rotten Scoundrels," "Parenthood,"

"LA Story," "Father of the Bride," "The Spanish Prisoner," "Bowfinger" and

"Bringing Down the House." Steve Martin has also established himself as a

novelist. He's just adapted his best-selling novel, "Shopgirl," into a film.

He's one of the producers, he wrote the screenplay and stars in it. Claire

Danes plays a young woman who's recently moved to LA where she's quite lonely.

She works at Saks at a counter selling elegant gloves for eveningwear, and

that's where she meets an older, wealthy and elegant man played by Steve

Martin.

(Excerpt of "Shopgirl")

Ms. CLAIRE DANES: (As Mirabelle) Who are you?

Mr. STEVE MARTIN: (As Ray Porter) Good point. I'm Ray Porter. Hi. How

are you? I know you can't be seen chatting up customers, so why do you just

meet me Friday for dinner at 8:00? You don't even have to give me your phone

number. You just show up, and if you don't, I'll just eat alone.

GROSS: I spoke with Steve Martin in 2003.

As an actor, particularly early in your career, your persona was usually very

extroverted. As a writer, like, your two novels are about really introverted

characters, and I think that's an interesting contrast.

Mr. MARTIN: Right. Well, I think actually that without, you know, being too

boring, analyzing my sort of stage act, that character--he was a bit crazy. I

was, on stage, very similar to this character. Really, it's like, on stage, I

was really just expressing a perverse thought on the way the world worked.

And I remember this one bit I did was--oh, I was so mad at my mother--I used

to scream it, of course--because she wanted to borrow $10 for some food. And

you know, there's just some kind of link here between this character, who just

sees things in the odd, odd way.

GROSS: All writers talk about, you know, facing the blank page and so on, but

it really is true that the difference between being an actor and being on the

set and being--you know, working with other people is so different than

staying at home and writing.

Mr. MARTIN: Right. You bet.

GROSS: Do you like that? Do you like that more isolated process of writing?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, you know, they complement each other so well, because,

like you say, movies are active and social, physical, and writing is solitary

and personal. And I never wanted to be an actor who sat home and waited for

scripts to come through the door. I mean, that would drive me insane, waiting

and hoping. And so I always wrote. I always did comedy, and I just like the

activity of it, you know. I just find that when I'm idle, which I always

enjoy, I always find that something comes up. Something pops up, so I'll get

out the computer and start typing.

GROSS: You know, I think it's hard when you're so accomplished at something

to try something that you're new to, as you were new to writing novels.

Mr. MARTIN: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. Yes.

GROSS: And, you know, when you're at the top of your profession in one thing

and then you're brand-new to something else, you can fail. You can be flawed,

and you can be very insecure. You have no track record. So did starting to

write bring out insecurities that you weren't used to? Because...

Mr. MARTIN: Oh, yes, absolutely. But there's a trick when you first start

writing, is that...

GROSS: Teach it to me, please.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, you don't have to show it to anybody.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MARTIN: When you're sitting there alone, and you haven't, you know, made

a deal with somebody to deliver a book, you're really on your own. And it's

like putting your toe in the water. You can have written something, and you

give it to a friend, or you ask someone's opinion. So you always fool

yourself, because--you know, the reason I say you fool yourself, ultimately,

you do want it to be out there, but you fool yourself by saying, `It doesn't

matter. It can be lousy. No one will ever see it if it's lousy.' And, of

course, they do see it, and sometimes it's lousy.

GROSS: So you would agree that self-delusion is an important part of

writing.

Mr. MARTIN: Very, very important. I really do. I think it is. Like, I

remember the first night I previewed my play, "Picasso at the Lapin Agile," I

had never written a play. I'd written screenplays. But I was in Melbourne,

Australia, and now it's 10 minutes before curtain, and all I could think is,

`What have I done?' I didn't know if there was going to be a laugh, you know,

anything. It could have been so humiliating. But then only, you know, 40

people would have seen it, and I could have gone home with my tail between my

legs. But I just want to add that I really don't have a tail. It's just a

figure of speech.

GROSS: Do you write many drafts before publishing?

Mr. MARTIN: What I do is I write without inhibiting myself, and then I

will--draft is not quite the right word in my head. I go through, and I start

editing. I start reading it, and I start reading it over and over and over,

which can get very tiresome, so sometimes I'll put it down for three months,

come back, read it again. Then I'll read it aloud to myself. And then I'll

read it to my dog. And I find that reading it makes you catch every word.

And to me, every word is important, because I'm a reader who gets bored

quickly, so I need to have these sentences on the move and be interesting all

the time. So I try to catch everything.

GROSS: Is your dog helpful when you're reading to him?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, he's my audience. I'm not looking for his response.

GROSS: You just need somebody to read to?

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah.

GROSS: Did you feel an obligation to be funny when you started writing,

'cause that's what people expect of you?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, no, because the first book, "Shopgirl," although it has

funny moments, I wouldn't call it a funny book.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MARTIN: But in "Pleasure of My Company," I actually wanted the book to

be funny, and I knew that I had a character who could be funny. And whenever

I start even a New Yorker essay, I have the idea, I think, `OK, what is the

potential of this?' I have no idea what the individual bits will be or

moments or anything, but does it seem rich or does it seem I'm going to run

out of steam in a couple of paragraphs? And I felt with this character, he

could really keep going. And it's a cliche to talk about the discovery of

character as you keep writing, but I found that my mind retains little details

of things I've written 40 or 50 pages ago. And so something that you wrote

that was very, very casual, a little aside, a little something he did comes

back at a certain moment, and it becomes big, because now this tiny little

thing impacts something else. And it's like weaving a web or weaving

something else, a caftan--I don't know--which I'm weaving. But that's what I

really like, is where the details start to add up.

GROSS: Well, you know, you've had your success in the book world and the film

world, and you've been on the best-seller lists, and you're probably the only

person to have hosted both the Academy Awards and the National Book Awards?

Mr. MARTIN: I guess I am.

GROSS: Yeah, I think so.

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah. I'll have to stop any Oscar hosts from hosting the

National Book Awards, so I can keep my uniqueness.

GROSS: So, I mean, I think that would probably give you a good seat as to

some of the differences between the two worlds, the film world and the book

world?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, the differences--you know, the book world is much, much

slower than the film world. I mean, the film world is so oriented to

promotion and getting the word out in certain ways, getting the word out in

very vibrant ways and very specific soundbite ways. And, for example, I mean,

here I am talking to you for 40 minutes about my book. This would never

happen about a film, I mean, in terms of the way a film is generally promoted.

But it's the way books are promoted. They're talked about in depth, in much

slower, slower ways.

GROSS: Well, and the numbers are so much smaller, too, aren't they?

Mr. MARTIN: Right, right.

GROSS: Like a best-selling book probably doesn't come close to the ticket

sales of a mediocre-selling movie.

Mr. MARTIN: Probably, yeah. But you know what I found is that when I started

writing for The New Yorker, I noticed I got more reaction from one essay--and

I'm talking about actual reaction that I could feel--I mean, people saying

things--than I did for movies. Like entire movies that cost millions and

millions of dollars to come out, and I would hear, you know, very little, or

somebody would say, `Nice movie,' or something. But these essays, they

started to--I guess because they're so intimate with the reader, they're so

intimately involved, that it stays with them longer. You know, a movie,

sometimes I walk out, I've forgotten it, you know, as I'm exiting the lobby.

GROSS: My guest is Steve Martin. The new movie "Shopgirl" is based on his

best-selling novel. He wrote the screenplay and stars in it. More after a

break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is Steve Martin. He stars with Claire Danes in the new movie

"Shopgirl." It's based on his best-selling novel of the same name. He wrote

the screenplay.

Well, I'd like to mention an essay of yours that I particularly liked, and it

was a personal essay about your late father.

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah.

GROSS: And, you know, it was about how he had wanted to act and had done some

amateur acting when he was young, and how you had, you know, kind of rocky

relationship. And one of the things you talk about is how you decided to take

your parents out to lunches every Sunday so that you could get to know them

better, and you realized that they were bickering all the time when you took

them out to lunch, so you really weren't getting anywheres.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, yeah, they were contra--right.

GROSS: And then you...

Mr. MARTIN: They were contradicting each other, so I decided with them to

take them out alone each, you know, one at a time.

GROSS: And that worked.

Mr. MARTIN: And without the other person there, I could get stories and, you

know, anecdotes and opinions and attitudes that I never would have gotten if

they'd been there together.

GROSS: I thought that was so smart to think of that. And then you also wrote

about how your father, when he was basically on his deathbed, said to you,

`You did everything I wanted to do.'

Mr. MARTIN: Right.

GROSS: I thought, wow, that's--what a zinger for...

Mr. MARTIN: Well, it's quite a moment, really.

GROSS: Yeah. Did you ask yourself whether he would think it was OK to say

that, you know, to write that? I guess one of the questions I'm asking is, do

you think the standard does or should change when someone that's no longer

with us--about what's too private to say about them? You know what I mean?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, I did not feel that that was too personal. I was very

particular about what I said. In fact, I ran the essay by my sister to get

her opinions on anything that might be too personal. But I didn't feel that

it was too personal because he was really demonstrating kindness there at that

moment.

GROSS: Because he'd been so critical comparatively in the past of you.

Mr. MARTIN: Right. Mm-hmm. Yeah.

GROSS: Right. You haven't written a lot of personal stuff. Most of your

writing is fiction or humor. And there's something that you wrote in an essay

in The New York Times that really meant a lot to me. I mean, I wrote it down

and stuck it in my computer so I could refer to it. I've mentioned it in a

talk. And this was in the context of talking about why you decided to have a

show of art from your art collection, something you used to be very private

about. And you said, `Being a celebrity can cause an accidental cheapening of

the things one holds dear. A slip of the tongue in an interview and it's easy

for me to feel I've sold out some private part of my life in exchange for

publicity.' I really thought that was so well-put, and I'm in the position,

you know, of asking the questions usually. And I know that that's always a

possibility--Do you know what I mean?...

Mr. MARTIN: Well...

GROSS: ...that both the interviewer and the interviewee risk cheapening

things. At the same time, I mean, I don't want that to happen; that's, like,

the unintentional occasional result. But, you know, I think you try on both

ends to be really sensitive to that, but I thought you just put it so well.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, I think, you know, the problem with, you know, being

interviewed as a celebrity is that, for example, you and I are talking now,

we're talking on NPR, and it's a very special circumstance; it's much more

detailed. It can be way more personal than, say, I would be on "Entertainment

Tonight." But--and so I'm willing, much more willing to talk about private

things in this circumstance. But what happens is this I might pay for three

years from now in an interview with "Entertainment Tonight" because they will

bring up maybe something I've said that's personal. Now actually that's kind

of diminished because, you know, I'm at a nice stage in my career where, you

know, I can get around and there's no sort of, you know, crazy invasion of

privacy or--and I also learned to keep relationships to myself because I've

realized that that kind of--I mean, I realized this a long time ago--that kind

of focus on your personal life actually damages it.

GROSS: You know, at the same time, I'm sure when you're doing an interview,

even if you just see it as a promotional interview, you want to be as

interesting as possible. So then again, there's the kind of trade-off

between, well, this'll make it more interesting; on the other hand, it's

personal, I'd just as soon not talk about it. So does that equation play out

in your mind?

Mr. MARTIN: No, it doesn't. It doesn't, because there's almost no way for me

to make an interview about a movie interesting. I've realized that. You

know, I've listened to Howard Stern, and he always plays celebrities'

interviews, and we all just sound ridiculous, you know. You know, and I know

that as I'm giving these interviews, I am that person that will be mocked

because there's just--you know, it's just not ultimately that interesting, you

know. So you have to kind of make up things. And you know, it's just a funny

business. It's like the worst day of your life, you know, when you have to go

talk about the movie you've made, especially if it's a...

GROSS: You're making me feel terrible.

Mr. MARTIN: Pardon me?

GROSS: You're making me feel terrible, 'cause...

Mr. MARTIN: No, no, it's not you. I'm talking about the soundbite industry.

GROSS: Do you get obsessive about things where you really--once you get into

it, you're into it?

Mr. MARTIN: Yes. But I think that's--there's other terms for that.

GROSS: Devoted.

Mr. MARTIN: Well--yeah, well, I remember an article in The New York Times

years ago called In the Zone(ph), and it talked about, for example, when a

basketball player is hot and he's just sinking these, you know, baskets one

after another. And they talked about people who are in the zone losing

consciousness of time. And that--or if you're--I mean, we've probably all

been stuck with a computer problem, and you've looked and suddenly four hours

have gone by while you're trying to solve it. And that to me is what writing

is. It just is so absorbing that time goes by; time goes by quickly, or it

stops.

GROSS: Yeah, but the problem is with writing, if time goes by quickly and you

don't like what you've written in that time, you feel like you've lost

something. Maybe that doesn't happen to you.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, you know, I don't write unless I'm ready. So usually I

find if you're in the zone, you usually like what you've written. And if I'm

not in the zone, I generally don't write.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MARTIN: I will edit at that point using what we call the monkey mind.

GROSS: What do you mean?

Mr. MARTIN: Somebody gave that to me years ago. It was like the monkey mind

was the--you know, there was your creative mind and then there was your monkey

mind, and your monkey mind was really consciousness. You know, and the monkey

mind should do the editing; it's the one that's not original; it's the one

that's imitative. And that's just a, you know, term for doing the slave work

of writing, when you're organizing...

GROSS: Boy, the editor community is going to be very angry at that

description.

Mr. MARTIN: No, no. No, I rely heavily on editors. I really need response.

GROSS: Steve Martin stars in the new film "Shopgirl," which is based on his

best-selling novel of the same name. He wrote the screenplay. This is FRESH

AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guest is Steve Martin. He starred in many films, including the

1998 David Mamet movie "The Spanish Prisoner." Here's a scene from it.

Martin plays Jimmy Dell, an apparently charming and wealthy man who befriends

Joe Ross, played by Campbell Scott. Here Jimmy is giving Joe business advice.

(Soundbite of "The Spanish Prisoner")

Mr. MARTIN: (As Jimmy Dell) You know what the man said about verbal

agreements; they're not worth the paper they're printed on.

Mr. CAMPBELL SCOTT (As Joe Ross): That's what my boss just said to me.

Mr. MARTIN: (As Dell) In re: what? I mean, what, what is he talking about?

Mr. SCOTT: (As Ross) Well, I've got a--oh, thank you.

Mr. MARTIN: (As Dell) You're welcome.

Mr. SCOTT: (As Ross) I did something for the company, and they owe me

something. I think I need to get it in writing.

Mr. MARTIN: (As Dell) I would. What do they owe you?

Mr. SCOTT: (As Ross) I think they owe me a lot of money.

Mr. MARTIN: (As Dell) What do you mean, you think?

Mr. SCOTT: (As Ross) I invented something for them. It's a work for hire;

they own it. But it's...

(Soundbite of phone being dialed)

Mr. MARTIN: (As Dell; on phone) Hello, is Mrs. DeSilva(ph) in? (To Ross) Who

told you it was a work for hire?

Mr. SCOTT: (As Ross) Well, they did.

Mr. MARTIN: (As Dell) You invented it?

Mr. SCOTT: (As Ross) Well, I...

Mr. MARTIN: (As Dell) I'm not a lawyer; I'm just a guy. Tell me, you

invented it?

Mr. SCOTT: (As Ross) Yes.

Mr. MARTIN: (As Dell) Uh-huh.

GROSS: "Spanish Prisoner" was written and directed by David Mamet.

Mr. MARTIN: Yes, absolutely.

GROSS: Oh, it must have been a pleasure to read his dialogue.

Mr. MARTIN: Fabulous. I loved doing it. You know, his dialogue is a

challenge for an actor because it's incredibly precise, including the `ers'

and `uhs' and they way we speak going back, retracing our words, just like I

just did, or like I just did. And so it's really fun to do that, 'cause you

really have to--you cannot, as you're speaking the dialogue, you can't get

ahead of yourself. You have to actually forget at that moment what you're

going to say next.

GROSS: What do you mean, that you have to forget it?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, in other words, if it's written that there's a hesitation

or an `er' and an `uh,' if you come up to it and you're prepared for it, it's

going to sound like, `er, uh.' It's going to be very dead. So you have to

talk as though you know what you're going to say but you don't. You have to

forget what you're going to say at that moment.

GROSS: And then you have to remember it again.

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah. Well, it's acting. You know what it is.

GROSS: That's right.

Mr. MARTIN: You know...

GROSS: So do you feel like you learned any new things from working with

Mamet?

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah, but it's--you know, he was a really good director for me

because he kept reminding me. You know, my character was supposed to be very

wealthy and very confident, and he kept reminding me of what that is, which is

nothing gets to you; no one can get to you. And that was a great reminder,

and it really provided me in the film with this kind of stillness and, you

know, ease with everything.

GROSS: I sometimes think about what it must have been like for you and Ricky

Jay, who was also in "The Spanish Prisoner," to work together, 'cause you

used to do magic, and Ricky Jay is, you know, one of the great living...

Mr. MARTIN: Right. Well, Ricky...

GROSS: ...prestidigitators? Is that...

Mr. MARTIN: Yes, yes.

GROSS: And, you know, master of card tricks and cons and the lore of magic

and carnivals and--so did you--yeah.

Mr. MARTIN: Well, Ricky Jay and I go way back. We go back to the late

'60s. He...

GROSS: Did you perform on the circuit together or something?

Mr. MARTIN: A bit, yeah. We actually met in Aspen, and he was working

someplace and I was working someplace. And I remember he was a book collector

and I was a book collector. And there was this beautiful rare book called

"The Expert at the Card Table" by S.W. Erdnase. And it was written,

published, I think, in 1907, and it was one of the early books that exposed

ways to cheat at cards. And of course, the author, if he had been known,

would have been beaten up. And S.W. Erdnase is Andrews written backwards,

and that was the real author, and we both sort of fought over a copy of that

book once.

GROSS: Who won?

Mr. MARTIN: I bought it, and then I gave it to him...

GROSS: Oh, you're so generous.

Mr. MARTIN: ...years later. Yeah.

GROSS: Do you remember the point in your career when people started to

realize, `He's smart'? You know, 'cause you played kind of stupid, you know,

wacky personas, right? And then eventually people realized, `God, he's really

smart.'

Mr. MARTIN: Well, you know, it's something you can never say about yourself

and believe it...

GROSS: Right

Mr. MARTIN: ...that you're smart. And so I don't--you know, I don't think of

myself as smart. I don't know--I mean, I almost feel like if anybody thinks

that, they're being cheated, because I also know people who actually are

really smart, and I've been around them. You know what I am if anything, I'm

diligent. But I've been around people who were smart, and I feel like my

relationship with them is my dog's relationship to me.

GROSS: (Laughs) Your dog's a good audience, let's not forget.

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah. Well, you know, my dog, he gets--you know, if I say, `Go

get the tennis ball,' he knows to get the tennis ball. But if I say, `Go get

the tennis ball and take it upstairs and put it under the bed,' then he's at

the point of `Duh.' And that happens--I find that happening to me when I'm

around really, really smart people, that there's a ceiling I hit of

understanding.

GROSS: And you're very funny on stage and on screen as you are. People

expect that you're just going to be, you know, a laugh riot when you speak in

person, too. And did you have to deal with the expectation that you're just

going to be, you know, a real cut-up in person?

Mr. MARTIN: Well, you know, I guess a little bit, but sometimes I can be a

cut-up. You know, there's a...

GROSS: Oh, yeah. Right. No, I realize that.

Mr. MARTIN: Yeah. Yeah. And you know, it's really people who don't know you

who expect that, and I don't really find myself in those circumstances that

much anymore, at least in private circumstances. I'm a, you know, pretty

regular sociable person or social person, so I think I'm--you know, I couldn't

do in private what I did on stage; people would not want to be around me, you

know, if I was that hyper all the time. And, you know, I've kind of worked it

out now, kind of figured out how to be.

GROSS: Listen, thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. MARTIN: Thank you. I really enjoyed it.

GROSS: Steve Martin's stars in the new movie "Shopgirl," which is adapted

from his novel of the same name. He wrote the screenplay. Our interview was

recorded in 2003.

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.