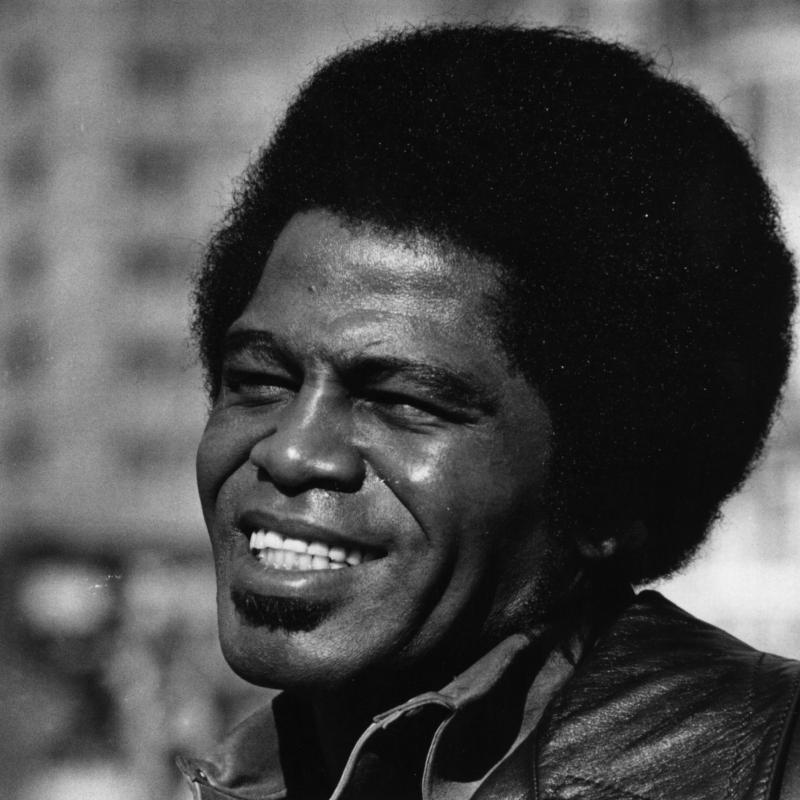

Remembering Singer James Brown

The "Godfather of Soul" passed away on December 25, 2006. Brown is considered one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century, blending gospel, rhythm and blues, and funk. His many hits include "Get Up Offa That Thing," "Funky President," "Papa's Got a Brand New Bag," "Super Bad," and "I Got You." The self-proclaimed "Hardest Working Man in Show Business" received a Lifetime Achievement Grammy Award and was one of the first musicians inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. This interview originally aired on Feb. 2, 2005.

Other segments from the episode on December 26, 2006

Transcript

DATE December 26, 2006 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: James Brown, "Godfather of Soul" who died on Christmas

Day, talks about his music in 2005 interview after publication of

his autobiography "I Feel Good"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross with our tribute to James Brown.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. JAMES BROWN: (Singing) "If you leave me..."

Backup Singers: (Singing in unison) "Leave me..."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "I'll go crazy..."

Backup Singers: (Singing in unison) "Oh, yes..."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "But believe me..."

Backup Singers: (Singing in unison) "Believe me..."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "I'll go crazy..."

Backup Singers: (Singing in unison) "Oh, yes..."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing" "'Cause I love you..."

Backup Singers: (Singing in unison) "Love you..."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Love you..."

Backup Singers: (Singing in unison) "Love you..."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Ohhh, I love you too much. If you quit me..."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's James Brown recorded in 1958. He was called the "Godfather of

Soul" but it's impossible to imagine funk or even hip-hop, without the

rhythmic innovations of James Brown. As a singer, band leader and performer,

he influenced generations of musicians around the world. James Brown died

Christmas morning at the age of 73. Later in the show, we'll hear from Bruce

Tucker, who collaborated on Brown's 1986 autobiography, and from two musicians

who played in his band, Maceo Parker and "Bootsy" Collins.

First, we have an interview with James Brown himself, recorded last year after

the publication of his autobiography, "I Feel Good." Here's someone who can

introduce him a lot better than I can.

(Soundbite from television or radio program)

Unidentified Man: So now, ladies and gentlemen, it is star time. Are you

ready for star time?

Audience: (In unison) Yeah.

Man: Thank you and thank you very kindly. It is indeed a great pleasure to

present to you at this particular time, national and internationally known as

the hardest working man in show business, the man that sing "I Go Crazy," "Try

Me," "You've Got the Power," "Think," "If You Want Me," "I Don't Mind,"

"Bewildered," million-dollar seller "Lost Someone," the very latest release,

"Night Train," "Let's Everybody Shout and Shimmy," Mr. Dynamite, the amazing

Mr. Please, Please himself, the star of the show, James Brown and The Famous

Flames.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Now we've all heard your emcee introduce you over the years.

Mr. BROWN: Yes.

GROSS: Why did you want an emcee to introduce you in this fantastic way?

Mr. BROWN: Well, because it's dramatic. It dramatizes a lot, and it's the

buildup what show business should be about. Show business should really be a

buildup, and then once you go into it, you, like, live it. But it should be a

great fanfare and a production. And that gives to the people the chords,

different chords, different kind of way to say it. The same as a minister

would do in a church, chords would do to his team. You have to have a way of

getting started. That's probably the best way that I know of. With a

dramatic introduction.

GROSS: Did you tell him what to say?

Mr. BROWN: Yes.

GROSS: And one of the things your emcee has always done was, like, put on

your cape, take off your cape. Why did you want to wear a cape?

Mr. BROWN: The cape is because I saw a wrestler by the name of Gorgeous

George, and Gorgeous George was a flamboyant wrestler. And he wore curls in

his hair at that time and he was really sharp and really different, a little

early for most people. You expect him to win if he didn't win, so it was kind

of a thing where he was a great wrestler, so it made great for his production.

It made him quite--Gorgeous George reminded me a lot of Hulk Hogan.

GROSS: The wrestler, yeah. Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. Now have you always

had your clothes made for you?

Mr. BROWN: Most of the time, I design them. I started wearing red suits

years ago, and they thought we were crazy. But we wanted people to say,

`There he is,' not `Where he is?' And the same thing applied to The Famous

Flames.

GROSS: I want to play "I Got You (I Feel Good)," one of your most famous

songs. You have two versions of this. The first one you didn't release. You

weren't happy with it. This was in 1964. What was wrong with the original

version? What made you think it's not ready yet, it's not right yet?

Mr. BROWN: You've got to get it where it synchs with the people or where

they're at, you know. "I Feel Good" was cut first with a jazz concept because

I have a broad and a great--more of ability to do more than one kind of music

or hear one kind of thing. There's so many directions that I go in, you know.

So what I did, I went back and at about 4:00 in the morning, I called--my

bandleader at that time was called--his name was Nat Jones. I recorded "I

Feel Good" in Chicago, and it was too sharp, too slick, had a baritone, you

know, and the syncopation was so sharp. So I had to cut something.

It was like, `I feel good. Da na na na na na na. Dit dum dum dum. Da na na

na na na na.' We gotta have staccato. Gotta hit right on all at once, `Dit

dum dum dum.' And then the drum, `dit dit dit dit dit dit dit.' So what did,

we wanted to get more of a funk feeling and a sanctified feeling, so we

changed it and slowed it down. `Ow! I feel good. Ja do da do da do da. Ja

da do do da. Ba dum.' That's two different kind of things, see. One is jazz

because of sharp mixes. The other one is kind of laid-back and gave it a

little rock 'n' roll feeling at that time as well. So we went with the

laid-back cut, because that fit the street and fit the dancing. It's a good

thing I could dance because by being able to dance, I could really tell that

the new arrangement, the new concept I had for it really fell right in place.

GROSS: What was the difference between the dancing you could do with the

second version compared to the first?

Mr. BROWN: Well, you could do the street dances. The first version--you

might do ballroom and everything with it, but the second version is for people

who get down in the street.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. BROWN: And we need street action. That's basically what's wrong with

the music today. A lot of it don't go street.

GROSS: OK. Well, let's hear both of these versions back to back, the

unreleased and the released version of James Brown, "I Got You (I Feel Good)."

Mr. BROWN: Well, you'll notice that the unreleased has a baritone in it...

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. BROWN: ...with a heavy sound, and the other one don't have the baritone.

You'll see the difference.

GROSS: Let's hear it.

(Soundbite from "I Got You")

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Ow! I feel good. I knew that I would now. Ow! I

feel good. I knew that I would now. So good, so good. I got you. Ow! I

feel nice like sugar and spice. I feel nice like sugar and spice. So nice,

so nice, 'cause I got you."

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. BROWN (Singing) "And I feel nice like sugar and spice. I feel nice like

sugar and spice. So nice, so nice, I got you. Wow! I feel good. I knew

that I would now. I feel good. I knew that I would. So good, so good,

'cause I got you. So good, so good, 'cause I got you. So good, so good,

'cause I got you. Hey! Oh, yeah!"

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Well, shortly after you recorded "I Got You," you recorded "Papa's Got

A Brand New Bag," and I want to quote something that you say in your new

memoir, "I Feel Good." You say, `"Papa's Got A Brand New Bag" changed

everything again for me and my music. I didn't need melody to make music.

That was, to me, old-fashioned and out of step. I now realized I could

compose and sing a song that used one chord or two at the most.'

Mr. BROWN: Yeah.

GROSS: How did you start reducing your songs to being more about rhythm than

about melody?

Mr. BROWN: What I did was that I brought--a lot of my songs had melody, but

like, "I Feel Good," that's a melody and all that stuff...

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. BROWN: ...but rhythm all the way through the song, and ours was just--I

mean, even rock 'n' roll stuff had melody, you know, but I went with more of a

jazz-concept gospel situation.

GROSS: Now at about this time, your beat really starts shifting from the two

and the four to the one and the three. Can you talk a little about...

Mr. BROWN: Well, actually...

GROSS: ...that shift? Yeah, go ahead.

Mr. BROWN: It started that with "Papa's Bag."

GROSS: Right.

Mr. BROWN: From that point on, it was one and three. And even before "I

Feel Good," "Papa's Bag" has a one and three.

GROSS: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. Can you maybe just clap for us the difference?

Mr. BROWN: Well, one is laid-back and the other's like `da dee da bum.' I

say, the one has syncopation, `Dat dat do dat dat do dat, bat dat dat do, bat

dat dat.' I mean, that's the difference. You count it off right on the one,

`Bam, do bang bang.' And then the other one you'd say, `One and a two' and

you'd be on the two, see, but two is the upbeat, and I'm on the downbeat.

That's the difference.

GROSS: How did you start doing that?

Mr. BROWN: Well, because of the fact that I'm a musician and I sang gospel

as well, and I know the difference. It's not `how,' which is easy to do.

`Why' would be the best thing. `Why' gives me a different feeling.

GROSS: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. And was it hard to convince the musicians that this

would work or did they get it right away?

Mr. BROWN: No, I paid them.

GROSS: (Laughs)

Mr. BROWN: Paid them, and they played what I wanted, and that was it because

they would have never agreed.

GROSS: They would have never agreed to it?

Mr. BROWN: They would have never agreed.

GROSS: Why not?

Mr. BROWN: Well, because it was in their head that Mozart, Schubert,

Beethoven, Strauss and Bach, Chopin and ...(unintelligible)...was correct.

And they'd tell me that I was wrong. So they thought that that was low in the

music. There's no low in the music. There's a freedom in music.

GROSS: We'll hear more of our 2005 interview with James Brown in the second

half of the show.

Coming up, an interview with Bruce Tucker, who collaborated with Brown on his

1986 autobiography.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Writer Bruce Tucker discusses James Brown's music and

co-authoring Brown's 1986 autobiography, "The Godfather of Soul"

TERRY GROSS, host:

We're paying tribute to James Brown on this edition of FRESH AIR. Bruce

Tucker co-authored Brown's 1986 autobiography, "The Godfather of Soul." Tucker

is a white writer who was teaching a course at Fisk University on the

autobiographies of black musicians when he realized there was a big gap.

James Brown hadn't written his story. Tucker convinced Brown to write an

autobiography and became Brown's collaborator. I spoke with Tucker in 1990,

after a new edition was published.

We'll let's listen to the first hit that he had, and this is from 1956. The

record was "Please, Please, Please." Would you like to say something about

this?

Mr. BRUCE TUCKER: Well, this is James' first record. He recorded a demo of

it in a Macon radio station, and it eventually got to King Records in

Cincinnati, and he went up there and the Famous Flames went with him, and they

cut it, and it was a hit. It was a big hit.

(Soundbite from "Please, Please, Please")

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Please, please, please, please."

Backup Singers #1: (Singing in unison) "Please, please, whoa, whoa."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Please, please, please."

Backup Singers #1: (Singing in unison) "Please, please, whoa, whoa."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Honey, please don't go."

Backup Singers #1: (Singing in unison) "Go."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Yeah, oh, yeah. Oh, I love you so."

Backup Singers #1: (Singing in unison) "Please, please, whoa, whoa."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Baby, you did me wrong."

Backup Singers #1: (Singing in unison) "So you done me wrong."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Well, well, you done me wrong."

Backup Singers #1: (Singing in unison) "Oh, you done me wrong."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "So you done, done me wrong."

Backup Singers #1: (Singing in unison) "Whoa."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Whoa. Oh, yeah. Took my love and now you're gone."

Backup Singers #1: (Singing in unison) "Please, please, whoa, whoa."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Please, please, please, please."

Backup Singers #1: (Singing in unison) "Please, please, whoa, whoa."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Please, please, please, please. Please, please,

please, please."

Backup Singers #1: (Singing in unison) "Please, please, whoa, whoa."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Honey, please, oh..."

Backup Singers #1: (Singing in unison) "Oh, whoa. "

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Oh, yeah. I love you so.."

Backup Singers #1: (Singing in unison) "Please, please, whoa, whoa."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: James Brown "Please, Please, Please," recorded in 1956, and my guest,

Bruce Tucker, wrote James Brown's autobiography with him.

Fill us in a little about his background. He came from a really poor

background.

Mr. TUCKER: Yes, he was born out in the woods in South Carolina and moved

into Augusta, Georgia, which was a wide-open serviceman's town at that time in

the late '30s, early '40s. Lived in a brothel with an aunt named Honey

Washington. They sold moonshine whiskey in addition to the other activities

that went on in that house. Eventually, the house was closed down by the

police. James then, oh, as a preteenager, I guess you would say, began

getting into trouble here and there. He broke into some unlocked cars to

steal some clothes, got caught and was sentenced to eight to 16 years in

prison for breaking into unlocked cars. Again, another extremely harsh

sentence. He served only three of those years. He wrote a letter to the

parole board, saying that he wanted to get out and sing gospel for the Lord.

He was known as "Musicbox" in prison because of his singing. He got out,

formed the group and then about six years later, there came "Please, Please,

Please," and then after that he conquered the Apollo Theater in New York and

went on from there to become the superstar that he remains.

GROSS: My guest is Bruce Tucker, who wrote with James Brown the book, "James

Brown: The Godfather of Soul," and as you say, James Brown is really the

godfather of funk, and the turning point for him in terms of starting to play

funk was his 1965 record "Papa's Got a Brand New Bag." What was different

about this record and what did James Brown have to tell you about it?

Mr. TUCKER: Well, at this point, he didn't have to tell me anything about it

because it's been so influential. It's something that we now can hear very

easily, but the difference in funk is that all of the rhythmic emphasis is on

the one, is on that first downbeat at the beginning of a measure, and it

really drives the music forward. You can hear it in this song in embryo and

then in later work quite clearly. And the other thing is the polyrhythmic

complexity which is what James is known for.

The other thing, I think, worth noting about this record is the date, 1965.

If you recall, soul of both the shouting and the churchy varieties didn't peak

until '67 or '68 and then more or less ended with the death of Dr. King. But

in 1965, James was already leaving soul behind for funk. I mean, it's an

amazingly revolutionary record if you put it in historical perspective like

that.

GROSS: I really like something he said to you about this record. He said

that he discovered his strength wasn't in the horn, it was in the rhythm. He

said he was hearing everything, even the guitars, like they were drums.

Mr. TUCKER: Exactly, yes. And I think that is the key to funk and the key

to James Brown. Everything is used percussively--the voices, the guitars, the

drums. He carried two and sometimes three drummers during this period on the

road. Yes, everything is used percussively. I think one of the difficulties

in making the case for a musician like James Brown for their importance is

that western music theory downgrades things that aren't important in European

classical music, such as rhythm, and so there's no means of adequately

notating it and so forth or appreciating it, and so we're in a sense trained

not to hear it, but it's there, and that's James' great achievement.

(Soundbite from "Papa's Got A Brand New Bag")

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Come here, sister, Papa's in the swing. He ain't too

hip about that new breed thing. Ain't no drag, Papa's got a brand-new bag.

Come here, mama. And get your babe to sleep. Not too bad, but he's fine as

he can be. Ain't no drag, Papa's got a brand-new bag. Do the jerk. He's

doing the fly. Don't...(unintelligible). Know he...(unintelligible). Do the

monkey, mashed potatoes. Jump back, cat. See you later, alligator. Come

now, sister, Papa's in the thing. (Unintelligible)...hip now, but I can dig

the new breed thing. He ain't no drag. He's got a brand-new bag. Papa, you

doing the jerk. Papa, you doing the jerk. You doing the flip just like this.

You doing the...(unintelligible). Everything and every night, the thing like

the boomerang. Hey! Come on. Hey, hey! Come on..."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: James Brown is kind of a riddle to me politically. I mean, he had

that really big, really influential record "Say It Loud, I'm Black and I'm

Proud" in 1968. He had supported H. Rap Brown. At the same time though he

supported Richard Nixon and played at Richard Nixon's inaugural. Can you help

reconcile those two different political parts of James Brown?

Mr. TUCKER: Well, I think that it's difficult to reconcile the parts of

James Brown because I think James Brown is deeply ambivalent about a great

many things, and I think it shows up in precisely those kinds of oppositions

that you set up. He gave money to the H. Rap Brown defense fund but he also

bought a lifetime membership in the NAACP. He was a great admirer of Dr.

Martin Luther King, and he's very close to Reverend Al Sharpton. He made a

record that was almost contemporaneous with "Say It Loud, I'm Black and I'm

Proud," called "America Is My Home," for which he took a great deal of heat

from a great many people. So I think there's a deep contradiction in him and

I think it's difficult to reconcile. I think it's difficult for him to

reconcile because this country has greatly rewarded him and viciously punished

him throughout his life, beginning from the time he was a child and right up

to the present.

So it's difficult to reconcile. The song "Say It Loud, I'm Black and I'm

Proud," which appeared in 1968, of course, cost him his crossover audience.

People became afraid to come to his concerts and so forth, and if you listen

to the song, of course, what you immediately notice is that it's almost a

children's song. There's a children's chorus on there singing the refrain.

GROSS: Bruce Tucker, recorded in 1990. He collaborated on James Brown's 1986

autobiography, "The Godfather of Soul."

Our tribute to James Brown will continue in the second half of the show.

I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of "Say It Loud, I'm Black and I'm Proud")

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Uh! Let your bad self say it loud."

Backup Singers #2: (Singing in unison) "I'm black, and I'm proud!

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Say it loud."

Backup Singers #2: (Singing in unison) "I'm black, and I'm proud!"

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Looky here. Some people say we got a lot of manners,

some say a lot of nerve. But I say we won't quit moving until we get what we

deserve. We've been 'buked and we've been scorned."

(End of soundbite)

(Announcements)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Saxophonist Maceo Parker discusses James Brown and his

experiences playing with him in 1989 interview

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross back with more of our tribute to James

Brown. He died yesterday morning at the age of 73.

Next we're going to hear from a former member of Brown's band, saxophonist

Maceo Parker. Parker has also played with funksters George Clinton and

"Bootsey" Collins, as well as the JB All-Stars. Here's Maceo Parker with

James Brown in 1969.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. JAMES BROWN: (Singing) "Yeah, yeah, yeah, sometime, sometime would be

low, sometime would be low. Call another brother, talking about Maceo.

Maceo, blow your horn. Don't put no trash, maybe some popcorn. Maceo, come

on. Popcorn. Ooh, do the funky walk. Uh, uh, yeah, yeah. One, two, three,

four. One, two, three, four. One, two, three, four..."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Maceo joined James Brown's band in 1964 and played with Brown for most

of the '60s and part of the '70s and '80s. I spoke with Parker in 1989 and

asked about the discipline James Brown demanded of the band.

Mr. MACEO PARKER: You know, you gotta be on time. You gotta have your

uniforms and stuff gotta be intact. You gotta have the bow tie, you gotta

have the bow tie. You gotta have them. You can't come up without the bowtie.

You can't come up without the cummerbund. Your shoes got to be--you know, the

patent leather shoes we were wearing at the time, you know, gotta be greased.

You know, you gotta have this stuff. This is what I expect, and that was OK.

GROSS: Did you get to--like, if you left the band, did you get to keep the

costume?

Mr. PARKER: No, no, no, no, no. No. He bought the costumes. He bought the

shoes and if for some reason you decided to leave the group, `Please leave,'

you know, `please leave my uniforms with somebody.'

GROSS: When James Brown started playing funk, he started putting the accent

on the first beat. When did he start telling you about the one in his music

and putting the emphasis on the one?

Mr. PARKER: He always liked to have a heavy one, that's what he felt. That

was his style. `GON-na have a funky good time,' doo de doo de doo doo.

That's where the one is, like right there.

GROSS: Was it hard for you to pick up on that or did it seem natural?

Mr. PARKER: It was hard when I had to solo in that I'm used to hearing the

accent being on two, like, if I would have done it, it'd be `Gonna HAVE a

funky good time' two and three and four. Gonna'--that's normally how

everybody was recording, and you could hear easily--I think their ears is

easily--it's easier to hear two and four, and that's where the back beat is

normally.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. PARKER: You know, ting ting DAT ting ting dat, like that, two and four,

but this was one. And at first, like I say, at first, it was a little

awkward, but you know, we became used to it.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. BROWN: Hit it!

Oh, how you feelin', brother?

Unidentified Singer #1: Feelin' good.

Mr. BROWN: You feelin good?

Singer #1: Feelin' good...(unintelligible)

Mr. BROWN: So much...(unintelligible)...brother How you feelin', man?

Unidentified Singer #2: I'm feeling all right.

Mr. BROWN: Not going to call your name. Don't want people to know you're in

here. How you feelin', brother? Hey...(unintelligible). Gettin'

down...(Unintelligible). Yeah.

(Singing) "We're going to have a funk good time. We're going to have a funk

good time. We're going to have a funk good time. We're going to have a funk

good time. It's gonna take a lot of bread We gotta take you high..."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Is it hard to work for the hardest working man in show business?

Mr. PARKER: It was hard but it was rewarding. It was fun because, you know,

you're working with somebody who has this title, hardest working man, so that

means you gotta do your part. You gotta keep up, and you never want him to

say, `Hey, man, you know, if I can do 10, 15 splits a night, at least you guys

can do and play a little vamp or whatever it is, you know, for 45 minutes.'

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Ow! When you kiss me, when you miss me, you hold me

tight. Make everything all right. I break out in a cold sweat. Maceo, come

on now. Brother, put it right now, Oh, let 'em have it. Oh, no! Mmm! Put

it on them. Mmm! Oh, try the horn. Get it. Funky...(unintelligible).

Excuse me while I do the boogaloo. Sometimes I clown, back up and do the

James Brown."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Saxophonist Maceo Parker with James Brown.

Coming up, bass player Bootsy Collins talks about his experiences in James

Brown's band.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Bass player William "Bootsy" Collins talks about his

experiences playing in James Brown's band in 1994 interview

TERRY GROSS, host:

The superheavy bass line in James Brown's 1970 hit "Sex Machine" was supplied

by Bootsy Collins. Bootsy continued to push funk in new directions, teaming

up in the mid-70s with George Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic, which

combined funk with science fiction and psychedelia. Then he formed the

spin-off group Bootsy's Rubber Band that was focused on his colorful stage

persona. I spoke with Bootsy Collins in 1994. Here he is with James Brown in

1970.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. JAMES BROWN: One, two, three, hit it!

(Singing) "Watch me! Watch me! I got it. Watch me! I got it, hey! I got

something that makes me want to shout. I got something that tells me what

it's all about, hah! I got soul and I'm superbad, I got soul and I'm

superbad, hah! Now I got a move that tells me what to do. Sometimes

it...(unintelligible)...hah! Now I got a move that tells me what to do.

Sometimes I feel so nice I want to tie myself to you, hah! hah! I got soul

and I'm superbad, hah!"

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Well, listen. I went back to James Brown's autobiography to see what

he had to say about you...

Mr. WILLIAM "BOOTSY" COLLINS: Yeah. Oh god.

GROSS: So he writes, "I think Bootsy learned a lot from me."

Mr. COLLINS: Yeah.

GROSS: "When I met him, he was playing a lot of bass..."

Mr. COLLINS: Yeah.

GROSS: "...the ifs, ands and the buts."

Mr. COLLINS: Yeah. He's right.

GROSS: "I got him to see the importance of the one in funk..."

Mr. COLLINS: Yeah.

GROSS: "...the downbeat at the beginning of every bar..."

Mr. COLLINS: That's right.

GROSS: "I got him to key in on the dynamic parts of the one..."

Mr. COLLINS: That's right.

GROSS: "...instead of playing all around it."

Mr. COLLINS: Yeah.

GROSS: "Then he could do all of his stuff in the right places, after the

one."

Mr. COLLINS: That's absolutely correct. Yeah. Absolutely correct.

GROSS: Was it hard to make the adjustment to playing on the one?

Mr. COLLINS: No, because I knew he knew something. I mean, you know, and I

was there to learn. It wasn't like, you know, this is my party, and I'll fly

if I want to. I knew it was James' party, you know, and whatever he knew, I

wanted to find out, you know, because he just had this--the band was the

tightest band in the land, and he had this thing going on and we wanted to

find out what the heck it was, you know.

GROSS: Had you been playing on the two and four before?

Mr. COLLINS: Well, actually, I started playing with the guitar and I wasn't

actually a bass player yet.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. COLLINS: So I was learning to play bass, you know, and I wanted to play

bass, so it was like, all those other if, ands and buts is what I was playing

when I picked up the bass, you know, and it was like, `Oh, you mean I got to

play on the dominant note. Ohh. OK.' So it was like all brand-new to me, you

know, and I just didn't feel like a normal bass player, you know, so--but by

James telling me that, it all kind of made sense, and once I started hearing

it, you know, what was actually happening when I did that, it was like, `Oh,

and then I can still do this? And I can still do that?' So it was a groove.

It was really a groove.

GROSS: Let me play one of the recordings you did with James Brown. Why don't

we hear "Sex Machine," and do you want to say anything about the rhythm you're

playing on this?

Mr. COLLINS: That's pretty much--the whole rhythm is what I figure I've been

doing ever since. When you hear "Sex Machine," that's pretty much where I'm

at now. Yeah.

GROSS: OK. Here we go.

(Soundbite from "Sex Machine")

Mr. BROWN: Fellas, I'm ready to get up and do my thing.

Unidentified Men: (In unison) Go ahead, go ahead!

Mr. BROWN: I want to get into it, man, you know...

Men: (In unison) Go ahead!

Mr. BROWN: ...like a sex machine, man...

Men: (In unison) Yeah! Do it!

Mr. BROWN: ...moving, doing it, you know?

Men: (In unison) Yeah!

Mr. BROWN: Can I count it off?

Men: (In unison) Go ahead!

Mr. BROWN: One, two, three, four.

(Singing) "Get up."

Unidentified Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Get up."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Stay on the scene..."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "...like a sex machine."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Get up."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Get up."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Stay on the scene..."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) ..."like a sex machine."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Get up."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Stay on the scene..."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) ..."like a sex machine."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Wait a minute. Shake your arms, then use your form.

Stay on the scene like a sex machine. You got to have the feeling, sure as

you're born, and get it together. Right on, right on. Get up."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Get up."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Get up."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: My guest is Bootsy Collins.

Now, tell me how your image changed when you started playing with James Brown.

What you did on stage, what you wore on stage.

Mr. COLLINS: Oooh, that's good, that's good. What I wore on stage. Oh,

man! Well, as you know or may not know, those were the days, like in the

'60s, getting ready to go into the '70s, but, you know, it was another kind of

movement going on, and kids were like coming up front and wearing like

bleached jeans and T-shirts and Afros, and, you know, the granny glasses and,

you know, we was all freaking out. We were having a freaking party, you know,

and I don't know, then here we are. We're playing with James Brown and you

know, we're in the army now. You know, it's like, whoa! You know so it's

like--but it was good for the fact that it kind of brought us off of the

street. We were out there doing what everybody else was acting crazy,

throwing firebombs and doing everything, you know. So getting with James kind

of brought us off of the street, and, you know, I think we kind of realized

that and, at the same time, you know, it gave us the opportunity of really

doing something that we wanted to do. So, you know, we kind of put everything

else in the back seat 'cause this is what we wanted to do. Even though, you

know, we wanted to dress crazy--we didn't know how crazy we wanted to dress

but we didn't want to wear suits, you know. We knew that, you know.

GROSS: So you were wearing matching suits on stage while everybody else was

wearing jeans and tie-dyed T-shirts.

Mr. COLLINS: Yeah, you know, while this movement was going on, the peace,

the love, that was going on, and here we are, you know, getting stuck with

wearing suits and patent-leather shoes, you know. But, at that time, you

know, the start of the soul was cool, you know. We said, `Well, we'll eat

this, because, you know, we definitely, you know, want to be with James,' you

know. So if you wanted to be with James, that's what you had to do.

GROSS: Bootsy Collins recorded in 1994.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: James Brown continues talking about his music in 2005

interview

TERRY GROSS, host:

Let's get back to the interview I recorded with James Brown last year.

Some of the musicians in your band became famous in their own right later on:

Maceo Parker, Fred Wesley, Bootsy Collins. And, you know, I interviewed

Bootsy Collins a few years ago, and one of the things he said--I mean, he

loved playing in your band--but one of the things he said is that it was hard

for him to be so disciplined. It was around 1970, the era when you were

recording "Sex Machine," and he said, you know, `Everyone was freaking out,

but we were standing up there being the tightest band in the land, having to

wear suits and patent-leather shoes, and you couldn't jump out in the audience

and freak out and act crazy, and that's what we wanted to do.' Did you know

that someone like, say, Bootsy Collins really wanted to, like, be wild and

crazy and you wanted this really tight, disciplined band?

Mr. JAMES BROWN: Well, I taught them organization. They didn't have

organization. And discipline was very important. You know, I wanted them

where they could play at West Point, as well as play the street on the corner.

I mean, West Point or the Navy Academy place. I wanted them to be able to go

anywhere. See, when I wanted to play "Papa's Bag" and stuff like that, I

could play for the president, and I could go and play for the people in the

streets. That's what you call being totally accepted and being totally

straight about what you felt.

GROSS: Now do you ever find musicians--I know you used to find musicians,

didn't you?

Mr. BROWN: Oh, yes, I'll do it now, but, you know, the musicians--now they

have a lot more respect and they're more intent on doing it right.

GROSS: So, Mr. Brown, what are some of the things you'd fined musicians for

back in the day?

Mr. BROWN: Oh, a lot of major things. I did a total program, like at West

Point. They've got to be clean, neat, the shirt got to be pressed, shoes got

to be shined, the suit got to be pressed. They've got to play correct. They

can't be looking off when they should be watching me because then they'll miss

something. I'll fine them. Because I don't have time to disturb what I'm

doing. I mean, we're always going to get through it, but by the same token,

those people who'd rather not get fined so they have a little more discipline,

and that's another situation. I'm sure the president of the United States has

ways of making people account for themselves.

GROSS: What's the biggest fine you ever gave?

Mr. BROWN: I don't know. Maybe 500.

GROSS: Now, I want to change musical directions for a second. And through

your career, you've recorded, you know, ballads as well as, you know, funk.

And in 1969, you made an album with a jazz band, the Louis Bellson band, and

it was mostly or completely ballads on here. And I thought we'd listen to one

of those ballads because it's a really different side of you. You know, we

were talking before about how you kind of focus more on rhythm than melody in

a lot of your songs, but here you are really focusing on the melody. Can you

tell us why you wanted to record this album of jazz standards with a jazz band

behind you?

Mr. BROWN: Well, I really liked Oliver Nelson because he made those horns

shout.

GROSS: And he did all the arrangements on the record.

Mr. BROWN: Yeah, he did. I wanted his stuff. But, you know, my concept was

so different. There's so many concepts. I needed a key to turn me on, which

was a little hard for me because it was Louis Bellson's song, who was the

drummer, and his wife was Miss Pearl Bailey. It was different. It was also

different for me to do "It's a Man's Man's World," because I did "What Kind of

Fool Am I?" a Sammy Davis thing. And I knew I wanted to go to the other side.

And I know people do it, and I know I wanted to do it, so it was really quite

an experience.

GROSS: Well, actually, that's the track I wanted to play, "What Kind of Fool

Am I?"

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "What kind of fool am I?" Yes, I...

GROSS: It's so interesting to hear you sing like this, so why don't we play

it, and I'll sit back and listen?

Mr. BROWN: You know, you sound like you was getting ready to sing something

there.

GROSS: No, I wish.

Mr. BROWN: OK. Let's take a listen then.

GROSS: OK.

(Soundbite from "What Kind of Fool Am I?")

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "What kind of fool am I, who never fell in love? It

seems that I'm the only one that I've been thinking of. Tell me what kind of

man is this, an empty shell, a lonely self where an empty heart may dwell?

What kind of lips are these that lie with every kiss that whisper empty words

of love that left me alone like this? Why can't I fall in love like any other

man? And maybe, maybe then I'll know what kind of fool I am."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: We'll have more of our 2005 interview with James Brown after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

(Announcements)

GROSS: Let's get back to our interview with James Brown recorded last year.

You know, pop songs have always been about love and sex, but they never really

used the word `sex' before in the lyrics, I think.

Mr. BROWN: Yeah.

GROSS: What made you decide to actually use the word `sex' in "Sex Machine"?

Mr. BROWN: Well, sex, I don't know, you're not far from it with the dancing

and all that stuff and the emulations that they do when they get on the floor

of the ballroom, two-stepping, the funky chicken or the James Brown, all these

different things. So--and that's what's in your mind if you go by a pool and

see young ladies out there in their bathing suits, swimsuits, because the men

don't...(unintelligible)...women do.

I decided I would use that term because we was at this dance. I mean, this

fellow and girl was at this dance. And she was just sitting there, and he's

sitting there. Nobody's doing anything. It was kind of just almost like

wallflowers till the fellow jumped up and said, `Get up. I feel like being

like a sex machine, and let's dance.' So that started it. That was the

concept.

And it's not about or relating to somebody else's girl or man. It's saying,

`I got mine, don't worry about his. The way I like it, the way it is. I

mean...(unintelligible)...fine. I got mine, don't worry about his,' you know.

GROSS: Was anybody worried, either your producers or disc jockeys about...

Mr. BROWN: No, it was produced by James...

GROSS: ...playing a record with the word `sex' actually in it?

Mr. BROWN: James Brown was the producer, so it wasn't no problem.

GROSS: OK. Here's "Sex Machine," recorded in 1970.

(Soundbite from "Sex Machine")

Mr. BROWN: Fellas, I'm ready to get up and do my thing.

Men: (In unison) Go ahead, go ahead!

Mr. BROWN: I want to get into it, man, you know...

Men: (In unison) Go ahead!

Mr. BROWN: ...like a sex machine, man...

Men: (In unison) Yeah! Do it!

Mr. BROWN: ...moving, doing it, you know?

Men: (In unison) Yeah!

Mr. BROWN: Can I count it off?

Men: (In unison) Go ahead!

Mr. BROWN: One, two, three, four.

(Singing) "Get up."

Unidentified Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Get up."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Stay on the scene..."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "...like a sex machine."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Get up."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Get up."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Stay on the scene..."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) ..."like a sex machine."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Get up."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Stay on the scene..."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) ..."like a sex machine."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Wait a minute. Shake your arms, then use your form.

Stay on the scene like a sex machine. You got to have the feeling, sure as

you're born, and get it together. Right on, right on. Get up."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Get up."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

Mr. BROWN: (Singing) "Get up."

Singer: (Singing) "Get on up."

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's James Brown. He has a new memoir called "I Feel Good."

How did you learn to dance and specifically to do splits?

Mr. BROWN: Well, I guess that it come from playing baseball...

GROSS: Wait a minute.

Mr. BROWN: ...because during that time...

GROSS: Most baseball players do not do splits.

Mr. BROWN: Well, now, they don't, but those years, Jackie Robinson, the

first black man came into major league baseball, and he was doing the split on

first base. And they thought that was absurd. They thought--they couldn't

believe it, but it was like ...(unintelligible)...clowning. There was another

black baseball team called the Indianapolis Clowns and the Kansas City

Monarchs before...(unintelligible). Those were Negro Leagues. And,

eventually, when Robinson got into major league baseball, he brought some of

those tricks with him. You know, we missed so much because had those black

men ever been able to play baseball then, it would be like the courts is

today. Ninety percent of all the players are black.

So you first, I think, danced when you were a kid, and you danced on the

street for pennies.

Mr. BROWN: I danced to pay the rent...

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. BROWN: ...for the soldiers.

GROSS: Tell us about some of those hardships, about what life was like when

you were very young. James Brown, your mother left when you were four, I

think, and you were--you lived...

Mr. BROWN: Yes.

GROSS: ...with an aunt. What was the house like?

Mr. BROWN: Well, it was very, very hard. I didn't have a place, because my

mother left. And my dad took me to see my grand aunt--Great-Aunt Anita Brown.

She raised me and kind of baby-sitted me while my daddy did basic menial work

that just didn't have any skill about it, but they had to go all over the

country to find work, somewhat like they're doing now, had to find a place

that common labor can make it, you know. They didn't have a lot of room for

common labor even in those days. That's why I'm telling kids to get education

today because you never know what's going to be out there for you and if

there'll be anything for you. So, it takes character and the contents of your

character, like Dr. King said. And people can know someone and don't even

know their name because--their upbringing.

GROSS: James Brown recorded last year. He died yesterday morning at the age

of 73. We're grateful for the music he leaves behind.

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

(Soundbite of music)

Unidentified Singer: (Singing) "You think I love you. Well, baby, you're

right. And to think I want to hug you, well, baby you're right. I want to

love you. I want to hug you, 'cause I, yeah, I need you so bad. Yeah, so

come on, just me and you..."

(End of soundbite)

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.