Paralympic Gold Medalist Chris Waddell

Chris Waddell has won metals in both the winter and summer Paralympic Games, competing as both an alpine mono-skier and a wheelchair racer. Waddell is currently competing in the Paralympics in Salt Lake City. He has already won a silver medal this week.

Other segments from the episode on March 13, 2002

Transcript

DATE March 13, 2002 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Chris Waddell discusses skiing in the Paralympics and

dealing with his paralysis

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

My guest, Chris Waddell, is competing in the Paralympics, the International

Olympics for Disabled Athletes, which are under way in Salt Lake City. On

Sunday, he won a silver medal for skiing to add to the five Paralympic gold

medals he's already won for skiing and wheelchair racing. He's competing

again today and tomorrow. Waddell lost the use of his legs in 1988 after

breaking his back in a ski accident. When he returned to the slopes, it was

on a monoski. I spoke with him Monday and asked him to describe the monoski

he's using in the Paralympics.

Mr. CHRIS WADDELL (Paralympic Athlete): The shock absorber is probably the

most important part of the whole thing, and it's a frame that's kind of almost

like taking a motorcycle frame without the wheels and without the handlebars.

So you sit on this frame about 18 inches off the ground and my feet are

extended in front of me, my knees are bent, and I have outriggers in my hands,

little like crutches with skis on the bottom. And the great part about it is

that if I do things well from the waist up, it basically, the ski does what

it's designed to do.

GROSS: And if not?

Mr. WADDELL: If not, I'm not making a very good turn.

GROSS: Right. Now you mentioned the shock absorber. How does the shock

absorber work? Is it like the shock absorber on a car?

Mr. WADDELL: It's exactly the same as a shock absorber on a car. It's

actually a motorcycle shock absorber, and the thing is, that for a regular,

able-bodied person skiing, you have your knees, hips and ankles to absorb the

bumps and the various terrain and stuff like that out there. I don't. If I

were skiing without a shock absorber on my monoski, it would be--you know, if

it were completely solid, it would be a miserably difficult ride. And I've

been really lucky. The company that I'm with, Yetti Monoski, has been working

closing with Penske and that's one of the things that we can continue to

improve is the shock and the ability to keep the ski on the snow, and if we're

able to do that, then we're able to take advantage of the technology of the

actual snow ski.

GROSS: Now are you strapped into the ski?

Mr. WADDELL: Oh, yes. Strapped in. Buckled in. I have a cover that covers

my legs so it adds to the aerodynamic--you know, it makes it more aerodynamic.

So yeah, I'm strapped in. I'm at one with the ski. The binding is a regular

ski binding that we click into, but it's also pinned with a cutter pin so that

it won't release, so I'm with the ski 100 percent of the time. If I crash,

I'm still with the ski, and sometimes that gets a little scary because you're

talking about 35 pounds of additional weight. But I don't want to lose this

ski. It'd be really ugly if I lost the ski and things would get really,

really ugly.

GROSS: Now you're seated on one ski. Why not two skis?

Mr. WADDELL: One ski is--I mean, there are some people out there who do

bi-skis. Most of the bi-skis right now are for higher-level entries,

higher-level paraplegics and quadriplegics, people who don't have as much

balance. The one ski for the monoski is just more performance oriented at

that point. Right now, one ski just enables us to make a better turn than two

skis do. And maybe that'll change in the future, but at this juncture in

time, that's the best thing we have going.

GROSS: How fast can you go?

Mr. WADDELL: I did not hear if they had a speed trap at the bottom of the

downhill, but one of the guys who was organizing the race was telling me that

he was guessing we were going about 70 miles an hour at the bottom there. So

it's pretty quick.

GROSS: Compare that to the speed of a skier who's skiing on their legs.

Mr. WADDELL: Well, it depends on which skiers you're comparing that to.

GROSS: Well, in the Olympics.

Mr. WADDELL: If you're talking...

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. WADDELL: Right. The Olympic--we're finishing at the women's downhill.

It's the women's downhill finish, so it's the same pitch. I think they were

going close to like 80 to 85, so we're, you know, 10 to 15 miles an hour

slower than they were.

GROSS: Mm-hmm. So pretty darned fast.

Mr. WADDELL: Yeah. Well, that's enough to get your attention.

GROSS: Now how do you keep your balance and control your center of gravity on

the monoski?

Mr. WADDELL: The monoski, what's interesting about it is it's like riding a

bicycle, where when you first start out, it's really difficult to find the

balance, and especially when you're going slowly, it seems like you're never

gonna find your balance, because, I don't know, it's same thing on a bicycle

where if you're trying to go slowly on a bicycle, it's much more difficult to

balance. Once you get going, you find that balance point, and once you've

found it, it seems like you're not gonna lose it. And so it's just really

similar to riding a bicycle in that it's pretty easy once you find the balance

point.

GROSS: You first started skiing when you were a child. How old were you?

Mr. WADDELL: Right. I was about three years old when I first started skiing.

GROSS: And you were how old when you had your accident?

Mr. WADDELL: I was 20 at the time of my accident.

GROSS: Mm-hmm. So you started skiing when you were about three, you had your

accident when you were about 20, so you were already skiing a lot by then.

Mr. WADDELL: Yes.

GROSS: What are the biggest differences for you between skiing on the monoski

and skiing on your legs like you used to do before the accident?

Mr. WADDELL: Right. What was interesting is when I first started skiing on a

monoski, it was difficult to learn because I was such a young kid when I first

started skiing that I didn't remember--I don't remember learning how to ski

the first time, and I had always kind of taken it for granted, it was

something that I did all the time, you know, every day, you know, 100 days a

year or something like that. And so learning to ski again was certainly

difficult. What's different is I have one ski. I don't have the ability to

step from one foot to the other. I don't have as much an ability to make a

lateral move, you know, a sideways move to try to gain a little bit of

distance, I guess, so--to help me get back on line, I guess is what I'm

saying. So it's much more difficult in some respects that you've got to

follow the ski around. You've got to make the ski go through the turn and

into the next turn, and so there's not as much of a--there's not as much room

for error. There's not as much of an opportunity to kind of cheat. You kind

of have to figure out where you're gonna go and what you're gonna do and stick

with that line.

GROSS: How do you stop?

Mr. WADDELL: Same way that anybody else would. You just get the ski across

the hill, edge a little bit to slow down and stop. It's really amazingly

similar, and there are times where I've completely forgotten that I'm skiing

on a monoski.

GROSS: Right. I guess what I find most difficult to understand about this

sport that you compete in now, and this is--I'll preface this by saying I'm a

physical coward.

Mr. WADDELL: OK.

GROSS: But I think if I took a bad fall and broke my back, that I'd devote

the rest of my life to, like, trying desperately to preserve the movement that

I had left.

Mr. WADDELL: What you had?

GROSS: Yeah. And the last thing in the world I would do would be to ski

downhill at 70 miles an hour and risk breaking an arm, you know, or anything

like that. Now obviously you don't feel that way.

Mr. WADDELL: Well, that's actually a really interesting thing that I think a

lot of people look at and say, `I wouldn't risk this. I wouldn't try. You

know, you've already injured yourself. Why do you want to risk anything

else?' And the hard part is that you want to start over again. That a lot of

what was taken away from me was the use of my body, was the use of my legs.

And I had to reclaim some pride in my body. I had to reclaim who I was to a

certain extent, and I had to prove to myself what was possible. And the fact

of the matter is, being an athlete, it makes my life a lot easier. It makes

my life a lot easier just getting around on a daily basis. And I think that's

what happens for a lot of disabled people. I'm lucky that I work closely with

one of my sponsors, with the Harvard Financial Services group, and that's one

of the things that I do for them is represent some of the possibilities that

are out there because for people who have had a traumatic injury, the hardest

part is getting started. And people always ask me, `Well, how do you do it?

How are you able to have achieved what you've achieved?' And the answer for

me is that I found something I love to do.

GROSS: How often do you fall when you're skiing?

Mr. WADDELL: How often do I fall? It depends on the day. The big thing is

that if I don't fall, I'm not pushing myself, so in training, I really need to

push myself to the point where I am going to fall, where I am going to find

that fine line between being in control and being out of control. And if I

can find that line, then that's something that I can use when I get into a

competition.

GROSS: Are there any tricks to falling on the monoski without hurting

yourself?

Mr. WADDELL: Hmm. Not really, I don't think. I mean, part of it is you are

much less likely to get hurt if you're being aggressive, if you're going for

it and if you're relaxed. If you tighten up and you're trying not to fall,

that's usually when you get hurt. So being calm and being at ease with the

sport I think oftentimes makes for good falls.

GROSS: Right. Have you had any serious injuries since monoskiing?

Mr. WADDELL: I've had a variety of different injuries and I've, you know,

broken my nose and strained my rotator cuff, and I've taken some crashes and

had some bumps and bruises. I haven't had anything that's really been serious

and, you know, I'm certainly knocking on wood at this point and hoping that I

avoid that in the future as well.

GROSS: Now over the weekend you won a silver medal.

Mr. WADDELL: Yes.

GROSS: How many fractions of a second did you miss gold by?

Mr. WADDELL: I think I missed gold by 29/100ths of a second.

GROSS: See, that's such an unfathomable measure of time. I mean, you can't

even say `by a nose,' 'cause a nose is like much bigger than that amount of

time is.

Mr. WADDELL: I think it ended up being at that speed, it was 7.8 meters that

I lost by over a course that's about two miles long.

GROSS: Oh, I see. So it's really more than by a nose, because you're going

so quickly.

Mr. WADDELL: Right, exactly. Yeah, we were going about 70 miles an hour at

the end of the race there.

GROSS: Right. So did you feel really victorious when you got the silver

medal, or were you disappointed that it wasn't gold?

Mr. WADDELL: Well, the biggest thing is when I'm competing, I have to look at

the competition is between me and myself oftentimes, and between the mountain

and me. And really, I felt like I had a good run. I felt like I conquered my

fear. I felt like I did what I needed to do. You know, I was disappointed.

I felt like I blew one turn close to the end, and that might very well have

been the difference. You're also, when you're competing against other people,

you're competing and you're working with the hope of winning, and so, yeah,

it's always a little bit disappointing, but the guy who beat me is a great

athlete and I certainly can't take anything away from him, and I put down the

best run that I could put down at that point, and that's certainly all I could

hope for.

GROSS: My guest is skier Chris Waddell. He's currently competing in the

Paralympics in Salt Lake City. We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH

AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Chris Waddell is my guest, and he's currently competing in the

Paralympics in the skiing events.

Can you tell us about the accident in which you got your injury?

Mr. WADDELL: I can tell you a little bit about it. I don't remember all of

my accident. I broke my back. I was skiing. I was warming up, preparing to

train, skiing with some friends at home, and I was testing a new pair of skis.

My binding came off prematurely. So I was skiing along, one of my skis popped

off, and that's all I remember of the whole thing. I crashed. I don't know

what happened after that. The shock made it so that I blacked out

essentially. I was conscious but I was in shock, and so I don't know what

happened. I broke a couple of vertebrae, collar bone, ribs and stuff like

that, and I was kind of in and out for a while as far as what I remember.

Going to the hospital and then being airlifted to another hospital and stuff

like that, but that's what I remember.

GROSS: Are you grateful you don't remember more?

Mr. WADDELL: I think that not remembering, you know, in some ways is a

blessing. It probably made it a lot easier to come back to skiing.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. WADDELL: Because I didn't--you know, it's not like I have this classic

flashback kind of thing...

GROSS: Right. Right.

Mr. WADDELL: ...you know, where you're thinking, `Oh, no. Here we are. I'm

in the same position again.' I don't remember that. It made it easier to

come back to skiing, and maybe in some ways it made it easier to move forward,

to progress in my rehabilitation and things like that. At this point in my

life, it's not a big deal one way or the other whether I remember it or not.

Maybe I'll remember, maybe I'll piece it together. At this point, I don't

think I'll remember anymore, and I'm fine with that. I don't need it one way

or the other, I don't think.

GROSS: At what point after the accident did you start thinking very seriously

about wanting to ski again?

Mr. WADDELL: In the time leading up to my accident, I was preparing for ski

season. I raced at Middlebury College at the time of my accident, and I was

preparing for the ski season, and I had goals as an able-bodied athlete, and

that fed right into my life after my accident. I was never told that I was

paralyzed, so as I was lying in my hospital bed, I was planning my return to

skiing while I was lying in my hospital bed. I didn't know the extent of my

injuries. I didn't know how I was going to be able to, you know, move

forward, but luckily, a couple of opportunities presented themselves. A

friend of a friend was doing a documentary movie on adaptive skiing, and she

asked me if I would be willing to ski in it. My coach at Middlebury, Barb

Bradford(ph), had been coaching at Mt. Hood and ended up coaching right next

to the US Disabled Team and came back all excited, and through the Friends of

Middlebury Skiing(ph) bought me my first monoski, which goes, you know,

between 2 and $3,000. So I was lucky that I had a tremendous amount of

support, and I was able to get back into skiing really quickly and really

easily.

GROSS: So when did you realize your legs were paralyzed? Is it something you

figured out yourself, or did someone actually tell you?

Mr. WADDELL: Nobody ever told me. Did I--I think I figured it out, but I

think there's also--for me there was a little bit of the ego of an athlete at

that point where maybe I was paralyzed at that point and I figured that what

applied to other people was not necessarily going to apply to me. And so

whether that was the situation at this point or not, I thought that I could

overcome it, and that was not necessarily the case, but I think that got me

through some of the hard part, the part of looking at this huge, traumatic

change in my life and being able to say, `You know what? I need to start

working now and eventually I will overcome this whole thing,' and maybe I

didn't overcome it in a literal way, but I think in a pretty figurative way I

was able to overcome it by finding ways for me to go forward.

GROSS: You need incredible upper-body strength for the monoskiing that you

did. What was your approach to building up your upper-body strength after you

lost the movement of your legs?

Mr. WADDELL: When I got back into skiing, I wanted to be a world-class

athlete. I wanted to be the best monoskier in the world, and that was my

goal, and I figured that if I was going to try to achieve that goal, I needed

to train like the best athlete in the world. So I started racing wheelchairs,

which is one of the best ways I can think of to build up my upper body. And

so I started racing wheelchairs, and that was my off-season training that

quickly snowballed into being a sport on its own. So I've actually competed

in the last two Summer Games in addition to the last three Winter Games. I

guess this is my fourth Winter Games, so it really--my off-season training is

an off-season sport that prepares me really well for the winter. I'm fit and

ready to go by the time November comes around.

GROSS: Did you work out with weights?

Mr. WADDELL: I work out with weights. I'm in the gym--like this past summer

I was in the gym five to six days a week, usually.

GROSS: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. I think what one of the most amazing things about

being a disabled athlete like you are, I mean, a lot of people assume when

they see somebody, for instance, in a wheelchair, that they must be very weak,

that they're in constant need of assistance of some sort, and you're really

strong. I mean, you can't use your legs, but...

Mr. WADDELL: Right.

GROSS: ...you know, the parts of the body you can use are really fit. So

it's this kind of paradox for somebody encountering you, you know. Part of

you doesn't work, but the other part is, you know, really top notch.

Mr. WADDELL: Right. Well, see, the fact of the matter is there's

certainly--it's not to say that there aren't things that are difficult,

because there are difficulties that I encounter every single day, and, you

know, it's a matter of--I mean, a flight of stairs is a difficulty. Getting

up a curb when I have something on my lap is a difficulty. And so there are a

variety of things that certainly are difficult, but they're also, by virtue of

being fit, it's a matter of being creative for me. It's a matter of trying to

figure out how I can achieve what I want to achieve, and, sure, some things

are gonna take a lot longer. It's difficult for me to put skis in the rooftop

box on my car, but I figured out that I can sit on the roof and pull my skis

up and put them in the box. And it's a lot easier if I get somebody else to

do it, but if the situation calls for it, I can do it myself, and I think that

that's part of what being an athlete is, and it's part of, you know, getting

the most out of life, I guess.

GROSS: You've competed in and won medals in several Paralympics. When you

were a teen-ager, did you compete with the goal of ultimately getting in the

Olympics?

Mr. WADDELL: I don't know that it was the goal. It was a dream, and by the

time I was a teen-ager, it wasn't all that realistic a dream. I don't

think--I was not going to compete in the Olymipcs. That is one of the things

that really, in a lot of ways, is a paradox for me, because I've risen to a

much higher level after a traumatic injury, which I think probably wouldn't

make sense to a lot of people, but, no, I mean, it was a dream as a kid to be

in the Olympics. It was never a realistic dream. Luckily now I can say that

I've been in, and this is my sixth Paralympic Games, and I can say that on a

few days I've been the best in the world, and I never, ever could have said

that prior to my injury. So it's a very strange twist of fate.

GROSS: Now you said that you don't think you're gonna be an athlete all your

life. Do you ever feel that there's a certain limit, like there's a certain

age that you'll reach and then you'll have to decide that's it?

Mr. WADDELL: Well, it's all an individual thing, I think. I think there are

people who certainly have been successful throughout, you know, their 30s,

into their 40s. And it's a matter of what you determine you want to do. I've

been an athlete for a long time in my life, and I think there comes a point

when you decide that even if you can continue to be successful, there are

other things that you want to pursue, and I think that I will come to that

point at some point, and I haven't decided exactly when that'll be.

GROSS: What do you think you would do afterwards?

Mr. WADDELL: That's a tough question. That's--in a lot of ways I feel like

I'm kind of approaching the end of my athletic career and I feel like a

college senior at this point, and people are asking me what am I gonna do, and

I don't know exactly what I'm gonna do. I don't have a firm plan of what I'm

gonna do, and part of it is that I think there are a lot of possibilities out

there, and I want to continue to pursue some of those things. I've done a

fair amount of speaking, motivational-type speaking, and I'm sure that's

something that I would continue to do in the future. That's something I very

much enjoy, and I think that'll be--I don't know if that'll be all of what I

do, but it will be a component. I've done some television work. I've been on

camera doing some television work. I'd certainly love to continue to do that.

And a lot of it depends on what the opportunities are that present themselves.

GROSS: Well, good luck to you and thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. WADDELL: Thank you, Terry. Appreciate it.

GROSS: Chris Waddell is competing in the Paralympics in Salt Lake City. He

won a silver medal on Sunday. Our interview was recorded on Monday. I'm

Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

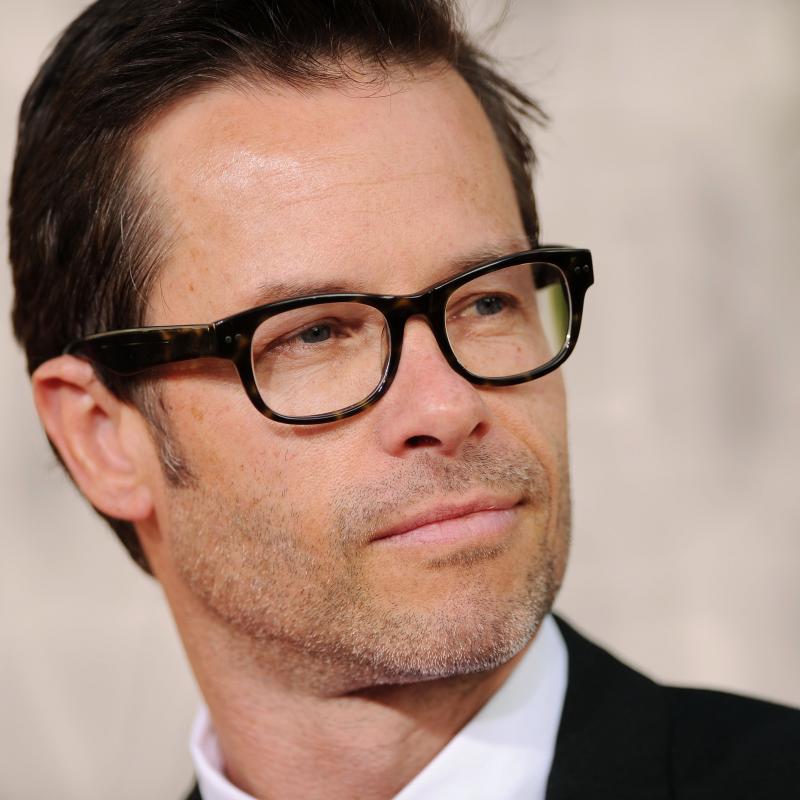

GROSS: Coming up, we talk with Guy Pearce. He's starring in two films

playing in theaters now, "The Count of Monte Cristo" and "The Time Machine."

He also starred in "Priscilla, Queen of the Desert," "LA Confidential" and

"Memento."

(Soundbite of music)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Guy Pearce discusses some of his film roles and his

life

TERRY GROSS, host:

This if FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

My guest, Guy Pearce, first became known to Americans for his role as a drag

queen in the comedy "Priscilla, Queen of the Desert." The Australian actor

went on to star in the cop drama "LA Confidential." In last year's

independent film hit "Memento" he played a man with a rare form of amnesia.

Now Pearce is in two movies currently in theaters, "The Count of Monte Cristo"

and "The Time Machine."

Let's start with a scene from "The Time Machine." Pearce plays a scientist at

the dawn of the 20th century who invents a time machine. In this scene, he's

traveled to the year 2030, where he meets a computerized hologram in the form

of a human, which is a databank of the world's knowledge. The time traveler

has some questions for the hologram, which is played by Orlando Jones.

(Soundbite from "The Time Machine")

Mr. GUY PEARCE (Actor): (As time traveler) Do you know anything about

physics?

Mr. ORLANDO JONES (Actor): (As hologram) Ah! Accessing physics.

Mr. PEARCE: Mechanical engineering. Dimensional optics. Pornography.

Temple causality. Temple paradox.

Mr. JONES: Time travel?

Mr. PEARCE: Yes.

Mr. JONES: Accessing science fiction.

Mr. PEARCE: No, no, practical application. My question is, why can't one

change the past?

Mr. JONES: Because one cannot travel into the past.

Mr. PEARCE: What if one could?

Mr. JONES: One cannot.

Mr. PEARCE: Excuse me, this is something you should trust me on.

GROSS: Soon after this encounter, Pearce gets back into the time machine and

eventually lands 800,000 years into the future, where he finds that humans are

the prey of underworld creatures that he will soon have to battle.

Now one of the things I imagine you don't learn in acting classes is who to

wrestle with monsters or creatures in a movie, so...

Mr. PEARCE: If I had've, I wouldn't have broken my rib doing it.

GROSS: Oh, did you break a rib doing it?

Mr. PEARCE: Yes, I did.

GROSS: What happened?

Mr. PEARCE: Well, I just have to run in and attack one of these monsters,

and one of these Morlocks, and after having done it about 15 or 20 times, I

started to realize I was in a serious amount of pain, and had actually cracked

one of my left front ribs, so it was most uncomfortable for a while after

that.

GROSS: Could you keep shooting?

Mr. PEARCE: Well, yeah, we did. I mean, I had to sort of pare down what I

had to do, and ironically, it was around the time that Simon, our director,

needed to sort of step away from the shoot, and so when he did that, we ended

up having a two-week break while the replacement, the sort of temporary

replacement director, came in, you know, so it actually worked out quite well

that I could have two weeks of sitting around at home without trying to climb

towers and wrestle more Morlocks, you know?

GROSS: I was reading some article about the making of "Time Machine" and it

was--I think it was a studio executive, maybe, who said that they had a

feeling that although you hadn't done this kind of film before that you could

really be a hero, and I thought, well, OK, when you take on a role--and you

really are the hero in this. I mean, you save a whole race of people. How

did you prepare yourself to play the part of the pure hero?

Mr. PEARCE: It's stepping out of, I suppose, the reality of what a person

does. I mean, it's funny in a way, because I don't consider myself at all to

be heroic, and I think it's a term that gets used far more in the United

States than it does in Australia. And so it's an unusual term for me, hero.

You know, I remember in in "LA Confidential," in that final sort of speech

that I have when I'm sitting in the interrogation room, I have to say to the

guys, you know, `You'll have to find another hero,' and I'm kind of talking

about myself and I remember having to try and really understand what that

meant, you know. And I guess it's about cultivating the childlike quality

within your mind or your imagination or your perspective, that enables you to

be able to look at people as heroes or bad guys or whatever, you know. To me,

there is a sort of a naive, childlike quality to that viewpoint, you know?

GROSS: Let me ask you about "Priscilla, Queen of the Desert." This is the

movie that Americans first got to know you through, and...

Mr. PEARCE: Yes, I guess so.

GROSS: ...and in this part you play a drag queen. The premise of the movie

is that one of your friends, who is a drag queen, gets a part in a drag show

at a resort in a town in the remote Australian desert, so this friend invites

you and another friend, who's a transsexual, played by Terence Stamp, to go

with him. So the movie is like your journey across the outback in this old

bus that you name Priscilla. Let me play a short scene. In this scene, the

transsexual played by Terence Stamp is not very happy that you were invited

along. The scene opens with you singing.

(Soundbite from "Priscilla, Queen of the Desert")

Mr. PEARCE: (As drag queen) (Sings) Our desert holiday, let's pack the drag

away. You take the lunch and tea, I'll take the ecstasy. (Censored) off, you

silly queer, I'm getting out of here. A desert holiday, hip, hip, hip, hip,

hooray.

Mr. TERENCE STAMP (Actor): (As transsexual) Why?

Unidentified Man: Why not? Look, he's turned into a bloody good little

performer.

Mr. STAMP: That's right, a bloody good little performer, 24 hours a day,

seven days a week. I thought we were getting away from all this (censored).

Mr. PEARCE: Two's company, three's a party, Bernadette, my sweet.

Mr. STAMP: We're unplugging our curling wands and going bush for this year.

Why would you possibly want to leave all this glamour for a hike into the

middle of nowhere?

Mr. PEARCE: Do you really want to know?

Mr. STAMP: Yes.

Mr. PEARCE: Well, ever since I was a lad, I've had this dream, a dream that

I now, finally, have a chance to fulfill.

Mr. STAMP: And that is?

Mr. PEARCE: To travel to the center of Australia, climb King's Canyon, as

a queen in a full-length Gaultier sequin, heels and a tiara.

GROSS: So, Guy Pearce, what are the favorite costumes that you actually did

have to wear for "Priscilla"?

Mr. PEARCE: I think one of the funniest ones, or the funniest situation,

really, was when we finally arrive in King's Canyon and we are there on the

top of this precipice that was really quite high. We weren't able to hike up

there; we had to actually be flown up there by helicopter and dropped off.

And I was wearing a fluffy white G-string and a funny, fluffy hat, and sitting

on the outside of the helicopter--I wasn't even on the inside of the

helicopter; I had to sit outside on this bar on the outside of the thing,

being flown up into King's Canyon, so I have a really unusual memory of that

costume and how uncomfortable it is to sit on the outside of a helicopter in a

fluffy white G-string.

But they were all brilliant, really. I mean, they were such fabulous

additions, I suppose, and helpful elements to our characters. They were

great.

GROSS: What was it like for you to wear drag? Did it bring out certain--like

different parts of your personality? Did you automatically start walking

differently, talking differently?

Mr. PEARCE: Yeah.

GROSS: Uh-huh.

Mr. PEARCE: I think so. I mean, in some ways, it's about needing to shed

any masculinity, in a way, when you're wearing that garb, because that then

becomes kind of comical, I suppose, you know. Actually, when we first did our

camera tests, and make-up and wardrobe tests, we had all decided prior to that

that we were going to go out in Sydney in drag that night, go to some clubs,

get drunk and have a fab old time, you know, and which we did. And it was

really the first time--we'd been in rehearsals for a couple of weeks, but we'd

been wearing jeans and track suits and whatever, you know--and so it was the

first time that it really came to life, and so much of that is about wearing

those costumes and those shoes and the wigs and everything, and just, I

suppose, you know, I mean, being an actor in Australia and being recognized,

when you're in drag, you're in disguise as well, and so you suddenly feel

inconspicuous, so you can kind of get away with doing whatever you want, you

know.

GROSS: My guest is actor Guy Pearce. We'll talk more after a break. This is

FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is Guy Pearce, and he's now starring in "The Time Machine."

Well, Guy Pearce, let me get to another one of your roles, and this is in the

film, "LA Confidential," and in this you play Ed Exley, a cop who's pretty

clean-cut and self-righteous, and very butch, not at all like your role in

"Priscilla," and you're very ambitious and you're willing to do anything to

get ahead, as long as it's by the book, and your ambition and your kind of

political know-how make you unpopular with a lot of your colleagues. You get

a promotion for supposedly solving a mass murder at the Nite Owl Diner, but

as more evidence surfaces, you begin to think you got the wrong guy. And in

this scene, you want to reinvestigate that murder, and you're seeking the help

of a fellow cop, played by Kevin Spacey.

(Soundbite from "LA Confidential")

Mr. PEARCE: (As Ed Exley) You make the three Negroes for the Nite Owl

killings?

Mr. KEVIN SPACEY (Actor): (As policeman) What?

Mr. PEARCE: It's a simple question.

Mr. SPACEY: Why in the world do you want to go digging any deeper into the

Nite Owl killings, Lieutenant?

Mr. PEARCE: Rollo Tomasi.

Mr. SPACEY: Is there more to that, or am I supposed to guess?

Mr. PEARCE: Rollo was a purse snatcher. My father ran into him, off-duty,

and he shot my father six times and got away clean. No one even knew who he

was. I just made the name up to give him some personality.

Mr. SPACEY: What's your point?

Mr. PEARCE: Rollo Tomasi's the reason I became a cop. I wanted to catch the

guys who thought they could get away with it. It was supposed to be about

justice. Then somewhere along the way, I lost sight of that. Why'd you

become a cop?

Mr. SPACEY: I don't remember. What do you want, Exley?

Mr. PEARCE: I just want to solve this thing.

Mr. SPACEY: Nite Owl was solved.

Mr. PEARCE: No. I want to do it right.

GROSS: That's my guest, Guy Pearce, along with Kevin Spacey, in a scene from

"LA Confidential."

Now Russell Crowe was also in this movie with you, so here you have a movie

set in LA, and two of the stars are Australian, you and Russell Crowe. How

did that happen?

Mr. PEARCE: If you really want to get technical about it, I'm actually

English and Russell's from New Zealand, so...

GROSS: Oh, OK. So you were born in England and--oh, that's true.

Mr. PEARCE: Yeah. I was born in England, Russell was born in New Zealand,

and we admittedly--well, I actually...

GROSS: Right.

Mr. PEARCE: ...grew up in Australia from the age of three, and I think

Russell came to Australia when he was about 21.

GROSS: Huh.

Mr. PEARCE: So, yes, we're Aussies.

GROSS: Right. So did you have to convince Curtis Hanson, the director of "LA

Confidential," that you could sound quite American?

Mr. PEARCE: Well, I mean, obviously I had to, and that just occurred in the

original reading that I went to. I was literally just one of however many

people coming in to screen test, and I found by that point, I mean, that was

early '96, and I'd spent, you know, a couple of visits throughout '95, going

to meetings and auditioning for people and this, that and the other, and one

of the interesting things was that every time I went to a meeting and spoke

the way I normally speak, it seemed to cause a bit of difficulty for people,

because they would say, `Oh, well, you might be able to work in this country,

but you're going to have to lose that accent.' So I started going to meetings

and readings and just affecting an American accent.

GROSS: So for you, what defines an American sound? I mean, to me, as someone

who really only speaks English, it's like it's--all I know is American

English, and so that seems to be like the basic to me. For you, it's

something different that you have to learn. What defines American English to

you, as opposed to Australian English?

Mr. PEARCE: Well, there are so many different kind of American accents and

different kind of Australian accents, it's hard to say. I mean, I guess the

first and most obvious general thing is the `R' sound. I mean, you would say

`car,' and we would say `cah.' And that is the most basic, as I say. It's a

simple difference. But funnily enough, there are some similarities, I guess,

in tone and pitch and melody between, say, the southern American accents, you

know, the sort of Texas--the slang, the slow kind of, you know, the laconic

kind of quality to some of the northern Australian accents. The Queenslanders

up there kind of talk like that, you know (drawls). I mean, there are

different shapes of words and sounds that there are many places that actually

have great similarities, but it could just be that simple thing, as I say, of

saying `arr' instead of `ah.'

GROSS: Did you have a language coach, or did you just pick this up on your

own?

Mr. PEARCE: Oh, look, we watched so much American television as kids in

Australia, and so many American films, that you become quite attuned to it,

you know.

GROSS: Did you know Russell Crowe before "LA Confidential?"

Mr. PEARCE: Not very well. Russell had come and done a guest spot on a TV

show that I did back in '85, and then the last time I'd seen Russell, he

head-butted me in a bar in Sydney in about 1992, I think, so that was--I

didn't know him very well.

GROSS: Right. Why did Russell Crowe head-butt you?

Mr. PEARCE: I asked him that very same question, and he said he was trying

to get my attention.

GROSS: There are other ways.

Mr. PEARCE: Yes, but not as unpredictable as a head-butt.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Guy Pearce, and his films

include "Priscilla, Queen of the Desert," "LA Confidential," "Memento," "The

Count of Monte Cristo" and now "The Time Machine."

You were born in England, but you grew up in Australia. What brought your

family from England to Australia?

Mr. PEARCE: My father was a fairly well-renowned test pilot in the UK. He'd

worked in the Royal Air Force, and worked for Hawker Siddeley. He was the

chief test pilot for the Harrier jump jet, and had also worked as a test pilot

for the Canberra-Lockheed Lightning and various other fairly well-renowned

aircraft. I think at the time we were in the UK living in Bristol. He was

offered the job as the chief test pilot for the government aircraft factories

in Australia to test a new aircraft, which was a short take-off and landing

aircraft called the Nomad.

He took the job; it was really just for a two-year stint, but after that two

years, Mum, who was from England, and my dad, who was originally from New

Zealand, didn't want to go back to England. They decided that, you know,

Australia was more in line with the kind of life they wanted to live, so we

stayed in Australia, and then--that was in about 1971, and Dad was then killed

testing an aircraft in '76, but we obviously still stayed in Australia.

GROSS: When your father was killed testing an aircraft, what happened? The

plane crashed?

Mr. PEARCE: Yeah. They were testing a new long version of the aircraft. It

literally took off. It was in the air for about 90 seconds, and due to sort

of government pressures they had to test these aircraft prior to them actually

being ready to be tested. They usually got through a series of wind tunnel

tests, etc., before they'd take them up in the air. So they'd take this

aircraft up in the air, 90 seconds in the air; most of the tail came off and,

of course, the aircraft just plummeted immediately and my father and the

designer were killed, and the navigator is now--he's still alive, but

unfortunately is a paraplegic.

GROSS: Had you braced yourself for something like that?

Mr. PEARCE: No, I was eight. You know, I hadn't really conceived of such a

notion, I suppose, until it actually occurred.

GROSS: What impact--I mean, did it leave you very afraid? Obviously you, I'm

sure, were shaken up that you'd lost your father, but in terms of your own

actions, did it leave you afraid to try new things? Because, like, look what

happened to your father; he was killed on the job doing something adventurous.

Mr. PEARCE: I think it actually in a rather morbid way probably makes one

more of a daredevil when it comes to taking risks or whatever. And that's, as

I say, from sort of a morbid perspective. I mean, there's a desperate part of

me that is trying to understand who my father was. And the fact that he went

to that extreme and ended up dying because of it I guess does kind of make you

have a rather morbid fascination with extremes. I mean, I certainly don't

have a fear of flying. I fly all the time, and I really enjoy it. And

funnily enough, after Dad died, I remember my mother saying to me, `Oh, you're

such a responsible young boy. You're so responsible.' And I have an

intellectually disabled sister, and there's really just the three of us, my

mum and Tracy, my sister, and I.

And so from a very young age, I was placed in the seat of responsibility, I

suppose, in regard to taking care of myself and taking care of my sister.

And, I don't know; I guess in conjunction with that or as a balance to that,

there's a part of me that wants to let go of that responsibility and actually

go and take risks. And, of course, you know, being on stage in front of

people or being in films that are presented to lots of people is not

life-threatening, but it's certainly risk-taking to a certain extent.

GROSS: My guest is Guy Pearce. We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH

AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is Guy Pearce. He starred in last year's independent film

hit "Memento," which is nominated for an Oscar for best screenplay. Pearce

plays Leonard Shelby, a man who is trying to find out who murdered his wife.

But the trauma has left him with a rare form of amnesia that prevents him from

making new memories. Here he is with a shadowy figure who is helping him

played by Joe Pantoliano.

(Soundbite from "Memento")

Mr. JOE PANTOLIANO: Leonard, look, you have to be very careful.

Mr. PEARCE: Why?

Mr. PANTOLIANO: The other day you mentioned that maybe somebody was trying

to set you up, get you to kill the wrong guy.

Mr. PEARCE: Well, I go on facts, not recommendations, but thank you.

Mr. PANTOLIANO: Lenny, you can't trust a man's life to your little notes and

pictures.

Mr. PEARCE: Why not?

Mr. PANTOLIANO: Because your notes could be unreliable.

Mr. PEARCE: Memory's unreliable.

Mr. PANTOLIANO: Oh, please.

Mr. PEARCE: No, no, no. Really.

Mr. PANTOLIANO: ...(Unintelligible).

Mr. PEARCE: Memory's not perfect. It's not even that good. Ask the police.

Eyewitness testimony is unreliable.

Mr. PANTOLIANO: That...

Mr. PEARCE: Cops don't catch a killer by sitting around remembering stuff.

Mr. PANTOLIANO: Right, I know that.

Mr. PEARCE: They collect facts.

Mr. PANTOLIANO: That's not what I'm saying.

Mr. PEARCE: They make notes and they draw conclusions. Facts, not memories.

That's how you investigate. I know. It's what I used to do. Look, memory

can change the shape of the room. It can change the color of a car. And

memories can be distorted. They're just an interpretation, they're not a

record. And they're irrelevant if you have the facts.

Mr. PANTOLIANO: You really want to get this guy, don't you?

Mr. PEARCE: He killed my wife. He took away my (censored) memory. He

destroyed my ability to live.

GROSS: How did you know you wanted to act?

Mr. PEARCE: The only recollection I really have was from a very young age,

probably about that time, eight, nine, 10. My mother used to take me to a lot

of theater. She was a big fan of theater. And we would go and see all sorts

of--a variety of stuff. And I feel like I have this memory as a kid of

watching these productions and wanting to be up there affecting people the way

I was being affected by the characters on stage, wanting to--I just, I

suppose, was so moved by the conviction that those characters had in the

performance that they were doing...

GROSS: But...

Mr. PEARCE: ...and found that incredibly appealing.

GROSS: ...at the age of 16, you won a state bodybuilding championship. Why

were you heading in that direction, and how big were those muscles?

Mr. PEARCE: Not so big. Well, I started going--yet again this, I guess, was

another influence of my mother. She started going to the gym when I was about

14 or 15, and I just went along with her. I mean, I played group sport at

school, but I was very much an individual and very much spent a lot of time on

my own or with my sister. And so I started going to this gym and just started

working out and just trying to get fit, you know. And the gym that we went to

was owned and was run by a married couple who were--one, she was a runner-up

Miss Universe a couple of times, and the husband, Joe, was a judge for the

IFBB, the International Federation of Bodybuilding.

So I was quite exposed to the world of bodybuilding at a pretty young age.

And he basically would say to me, `The work that you're doing, the physical

work you're doing, is having quite an amazing, immediate response. And, you

know, if you want to consider it, then, you know, we should enter you in some

competitions.' And, you know, I saw competitions and I would see the videos

of these competitions. And to me it was kind of, I guess, another form of

being on stage and performing, you know. And I was fascinated with the whole

notion of actually creating yourself, and I still am; not so much in actually

bodybuilding, but I'm more interested in spiritually creating or developing

yourself, or physically, you know, creating yourself in the characters that I

play, I suppose.

GROSS: Yeah, but if you spiritually develop yourself, you can't show off like

if you've got lots of muscles.

Mr. PEARCE: No, that's right. Hence the reason why I'm not so interested in

bodybuilding anymore.

GROSS: So do you still have muscles as big as they were then or did you let

them...

Mr. PEARCE: No. Well, you saw "Memento." I didn't have much in that. You

know, I certainly--I mean...

GROSS: Well, after seeing your cheekbones, you know, I was going to tell you

you need to eat more.

Mr. PEARCE: I get told that all the time. So I'm kind of used to that now.

GROSS: Now when you were 18, you were cast in a nighttime soap opera in

Australia called "Neighbours." I have not seen the show. I doubt many

Americans have. I read that you became a teen heartthrob. Fair description?

Mr. PEARCE: Well, to a certain extent. I mean, you know, I think, you know,

the dog on the show was really popular as well. So, I mean, you know, it's

just that thing of being on a show that's watched by lots of teen-agers. They

tend to get a bit excited about seeing you in real life or--you know, there

was obviously a lot of stuff with us on magazine covers, etc., you know.

There was a bunch of us in the show. It wasn't like it was just me or

anything.

GROSS: Right. Right. Well, you know, when you're a star at that age and

teen-agers fantasize about you, I'm sure they fantasize about this just

incredibly interesting, constantly, you know, very sexy kind of life. Did you

often think about what your real life was like compared to what your fans were

probably imagining your life was like?

Mr. PEARCE: Oh, yeah. I mean, I was a complete loner, you know. I mean, I

spent a lot of time at home, on my own, and really didn't have a great social

life. And I found that going out in public was even more difficult then than

it was when I was even younger, because suddenly I would get recognized and

hassled and confronted or just questioned or--I just didn't deal with the

attention very well, I suppose. And so I then started to cultivate a really

sort of small, intimate group of friends, and I would spend a lot of time at

home on my own. And music has been a really important part of my life, so I

really spent a lot of time recording music at home and working in my studio

and rehearsing music, etc., etc. So that's what I did.

GROSS: And is this music singing, playing, both?

Mr. PEARCE: Singing primarily, but playing, dabbling in a variety of

instruments. And I became very interested in the notion of recording and the

sort of technical aspect of recording and arranging. And I would have all

these musicians come over and play. And, you know, that still goes on really.

It's like a glorified hobby.

GROSS: But you don't have a CD, a professional CD, right?

Mr. PEARCE: No. No. And I don't--you know, it's funny, as the years go on,

the need to actually get it out publicly like that sort of diminishes, I

guess. I mean, I play gigs at home and just random stuff, you know. The nice

thing about it is it actually makes one really question why music is such an

important part of one's life and why one feels the need to express--you know,

why I feel a need to express myself through music. And it is just about that,

expressing oneself through music and playing music with other people and

rehearsing with other people and recording but not turning it into, not taking

it into that public arena and sort of turning yourself into a known entity

because of it, you know.

GROSS: Well, Guy Pearce, thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. PEARCE: A pleasure. Thank you.

GROSS: Guy Pearce is now starring in "The Time Machine" and "The Count of

Monte Cristo."

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.