Transcript

DATE February 9, 2006 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

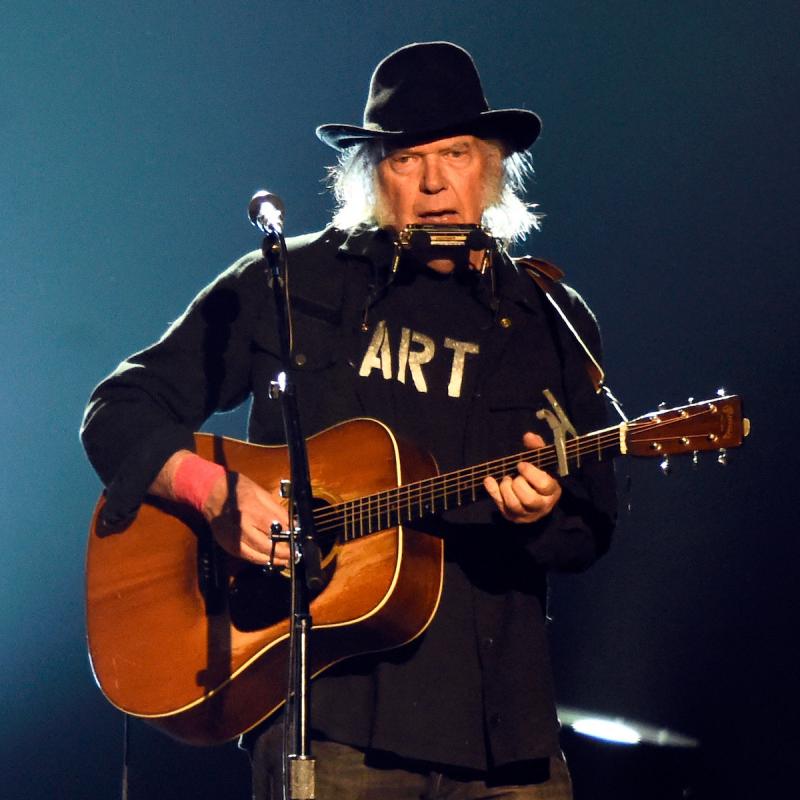

Interview: Singer Neil Young and director Jonathan Demme discuss

new concert film, "Neil Young: Heart of Gold," and the songs Young

performed which were written and recorded at a time when he was

dealing with brain aneurysm

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

My guest, Neil Young, gives a very moving performance in a new concert film

directed by Jonathan Demme, who's also with us. It was filmed in Nashville at

the Ryman Auditorium, the former home of the Grand Ole Opry, with a band of

old friends. The music is pretty remarkable, so is the story behind it. The

new songs Young performs were written and recorded in the period when he was

diagnosed with and treated for a brain aneurysm. Those songs were first

recorded on his album "Prairie Wind" which was released over the summer. In

the film, Young also performed some of his classics like "Old Man," "I Am a

Child" and "Heart of Gold." The film was called "Neil Young: Heart of Gold."

The director Jonathan Demme also made the 2004 version of the "Manchurian

Candidate," "Philadelphia," "Silence of the Lambs" and "Something Wild."

"Heart of Gold" opens in select theaters this Friday, but the soundtrack won't

be released until the spring. So the versions of Young's new songs that we

will hear are from his album "Prairie Wind." Let's start with "It's a Dream."

(Soundbite of Neil Young's "It's a Dream")

Mr. NEIL YOUNG: (Singing) "In the morning when I wake up and listen to the

sounds of the birds outside on a roof, I try to ignore what the paper says.

And I try not to read all the news. And I'll hold you if you had a bad dream.

And I'll hope it never comes true. Cause you and I've been through so many

things together. And the sun starts climbing the roof. It's a dream, only a

dream. And it's fading now. Fading away. It's only a dream. Just a memory

about anywhere. Just stay."

GROSS: I asked Jonathan Demme what it was like to approach Neil Young about

making a film at a time when Young was dealing with a brain aneurysm.

Mr. JONATHAN DEMME: The turning point, I thought I was contacting him at was

that he had just created what was arguably just one of the major master works

in this master's artistic life. I just heard these songs that he was sending

up from Nashville, and thought, `My God, this is really, to capture this stuff

somehow or other on film could be really amazing.' I responded to the

emotional dimension. I responded to my own emotions. I got very emotional as

I heard this stuff, and it just gave me a lot of confidence to pursue the idea

of, if we were able to stage a concert in Neil's ideal location, that would be

the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville, Tennessee, with his ideal group of

musicians, that we would probably wind up with something that would be

incredibly singular amongst music on film and the music on film category, and

something that I know I would feel very privileged to be a part of.

GROSS: Neil Young, this is, to me, just an incredible part of the story. The

way I understand it, you find out you have this aneurysm on your brain, and in

a couple of weeks, you are going to get a procedure to fix it or do away with

it or whatever the medical term is, and so you decided to book a studio in

Nashville and record a new album except you haven't written the songs yet. So

you go to Nashville with the intent of writing these songs before the

procedure is done. Do I have that story right?

Mr. NEIL YOUNG: Well, it's kind of right.

GROSS: You tell it. You tell it.

Mr. YOUNG: Really, really what happened, I was at the Rock and Roll Hall of

Fame inducting Chrissy Hind of the Pretenders into the Hall of Fame and

visiting, and I was planning to go to Nashville the next day to record, and I

had one complete song and it was enough to go in, and I kind of had confidence

that if I was going to go in there and get started, that it would start things

going, and I would probably write more because I would be in a situation where

if I wrote it, I could put it down right away. And so the Hall of Fame came

along, and I did my presentation to Chrissy and the Pretenders, and then I

went home, and then the next morning I woke up and I was shaving and I looked

out the window, and there was this--you know how you get something caught in

your eye sometimes and it looks like one of those micro-being thing, a little,

you know, long, looks like DNA or something floating around on your eye, and

you're going, `Wow,' you know, `look at that, it's a science project.' So I

was--I had one of those, but it looked different to me. I said, `That's a big

one, I've never seen one like this.' Then I closed my eyes, and it was still

there. So then I started pushing on my eye, trying to move it around like you

usually would be able to, and it just didn't move. So I said to myself,

`Well, this is something on your brain, not on your eye.' So that became a

little bit--by then it had grown to cover half of my field of vision, and

everything to the left of it was just kind of looked like a mercury, silvery

kind of a thing moving around like reflections on water, and everything to the

right of it was clear as a bell. There was this line, a shard of glass or

something, right through the middle of it that was really vibrating. So I was

experiencing this, and it was becoming a little bit disorienting because just

having so much of your vision kind of out to lunch was--the whole thing was

disorienting. So I decided at that time that I was going to get it checked

out, and I had a doctor friend that I had just seen the day before for an

unrelated thing, and so I called him, and he said come on in. So I went down

there, and by then, it had gone away. It only lasted about 25 minutes. So

when I went down there, they took me to all these--the Dr. Positano took me

to all of the experts in fields that were related to this. And so I saw five

doctors, and they did a bunch of tests and things on me, and they're trying to

figure out what it was, and they never came to a conclusion of what it was,

but during the searching, they found this aneurysm which was completely

unrelated to...

GROSS: It was unrelated?

Mr. YOUNG: Yes. It was unrelated. It was kind of an accident that they

found it. And the visual disturbance turned out to be a visual migraine, and

now I just simply take a little aspirin, and that doesn't help anymore. Of

course, you know, I guess someday I will have to take a little more aspirin or

something. I don't know. Hopefully, everything will be OK there, but the

aneurysm had nothing to do with it.

GROSS: Oh, you're lucky.

Mr. YOUNG: Yeah. So I was fortunate to have a great neurologist who I'd met

and his name is Dexter Sun. And he is there in New York, and he told me in

his Chinese way that I had had this aneurysm for a hundred years and is

showing me on the big, you know, readout, that they had this big piece of

film, and you could see the thing kind of looked like Florida hanging off of

the United States. And I was looking at it, and it kind of scared me at

first, and then he said, you know, `Neil,' he said, `you've had this for a

hundred years. There is nothing to worry about. For you, it is nothing to

worry about. For me, I have to get rid of it as soon as possible. It has to

go. We have to get rid of it. It has to be gone from your head.' And I said,

`Well, how do we do that?' And he said, `Well, I need to make some calls and

we're going to set up an appointment for you with this surgeon, Dr. Gobin, at

New York Presbyterian.' So they did that, and I went. Dr. Gobin wasn't going

to be in for a couple of days, so I had three or four days between when he was

coming in, and then so rather than sit around, knowing that I had an aneurysm

and just sitting in New York with my aneurysm, I decided to go to Nashville

and do what I was going to do in the first place and then fly back. So I went

in there, and I recorded the "Painter," and then I recorded--the next song I

wrote was "I Wonder." The next day I wrote that, the evening after the

"Painter" and the morning, the following morning I wrote that and then we

recorded it, and then I wrote "Falling Off the Face of the Earth" that night

and the next morning and we recorded it, and then I went back to New York and

met the Dr. Gobin, and we scheduled the procedure for 10 days from that

point, and then I went back to Nashville and finished the record.

GROSS: So, was your life in jeopardy at this point?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, you know, it's one of those things where your life is in

jeopardy if you have this thing. And on one hand one doctor was telling me

everything was OK, you know, I can fly, `You can do whatever you want to do.

You've had this for a long time, there is no reason to change what you are

doing and just go on with your life, and we will take care of it here in a

week or two, and everything will be fine.' And other doctors were telling me,

you know, `Don't lean down to tie your shoes,' you know. `Have someone else

tie your shoes for you. Don't put your head down,' because, you know, if you

put your head down really fast and then bring it back up, there is a lot of

pressure happens there or something. So, you know, this is kind of turning

into a medical show, but that's OK.

Mr. DEMME: The great American actor Trey Wilson, who played Nathan Arizona

in "Raising Arizona," and I got to work with him in "Married to the Mob," he

was perfectly healthy, and he was in a restaurant one night and his aneurysm

exploded on him, and that was it.

GROSS: Oh, really.

Mr. YOUNG: Yeah. It's like, you know, if it goes off, you're finished. So,

and this was an ugly one. It's a series of bubbles that form, like if you

think of one of your arteries as like a bicycle tube...

Mr. DEMME: I'd rather not.

Mr. YOUNG: ...which is easy for me to do. So, I have a Schwinn brain. So,

anyway, I was riding along on my balloon tires, and, suddenly, I realized

there was this huge bump on my tire. And then, you know what happens is,

that's a weakness in the wall of the vein, and so the pressure makes this

bubble come out. And I had a series of six or seven bubbles on top of

bubbles.

GROSS: Gee!

Mr. YOUNG: So there was just--it was getting thinner every time it happened.

So it was obvious that Florida had to go, you know. We had to get rid of that

state.

GROSS: You know that classic movie plot, you go to the doctor, you find out

you only have two weeks to live or six months to live and the rest of the

movie is like, `What are you going to do with that time?' And it's like you

find out, it's conceivable that you only have a couple of weeks to live, you

know. And what do you do? You go into the studio and you write songs. I

mean, if given your choice, would that have been the thing that you most want

to do if you felt that your time might actually be limited?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, you know, there was really no way of knowing how long this

thing would go on, and it had gone on maybe my whole life, building to where

it is now. We don't know how long it took to get to where it was, but

something told me that the thing to do was do what you do. Just do what you

were doing before and just keep on going. So when I'm making music and

writing songs, and, you know, I had my wife with me, Pegi was there. She was

helping on the record. So everything was good. We were together, and we were

doing what we love to do, so we decided that's how we're going to spend our

time.

Mr. DEMME: I heard that when you were down in Nashville cutting the record,

in the midst of all of this, that you were eating barbecue every night and

just really, really chowing down.

Mr. YOUNG: No. There's no truth to that. That's one of those Internet

rumors.

GROSS: My guests are Neil Young and director Jonathan Demme. More after a

break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guests are Neil Young and director Jonathan Demme. Their new

performance film, "Neil Young: Heart of Gold," features songs that Young wrote

last year right after he was diagnosed with a brain aneurysm that has since

been successfully treated.

I want to play the song "Falling Off the Face of the Earth." You mentioned

this is one of the songs you wrote right before the procedure, and it's just

such a beautiful song and it's about, like an older person's love, not like

new romantic `I've just fallen in love' love, but the kind of love that you

have with somebody who you've been with for a very long time. It's a very

beautiful song. Would you say a little bit about writing this song, Neil

Young?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, writing "Falling Off the Face of the Earth" is really a

case of, I had a melody that I was writing that I had just come up with that

night, and then I was going to bed and I couldn't come up with the lyrics, but

I had a melody and chord changes. So I thought, `Well,' you know, `I'll just

go to sleep and I will wake up in the morning and start playing the changes

and the words will be there.' So, I checked my voice mail, and I had a message

from Jim Jarmusch, who did my film, "Year of the Horse."

GROSS: An early concert film?

Mr. YOUNG: An early concert film of "Crazy Horse" which is like the--almost

the polar opposite of this film in some ways because of the musical content.

But, anyway, Jim and I are good friends and he sent me, left a voice mail, and

it seemed, I'm not sure if he knew I had this aneurysm or if he didn't, but he

was, I think he did, but he was just thinking about me, and so he left me a

message and some of the phrases that are in the message, I played it again and

I wrote down some of the phrases that he used. And then, you know, in the

morning, I had the song all done because some of the phrases that he used in

the voice mail were in the--I just used them out of context in the song and

kind of opened up the door for everything else, so the chorus and everything

all just fell out.

GROSS: Did he say...

Mr. YOUNG: You know once you get started...

GROSS: Did he say something like feeling like he's falling off the face of

the earth?

Mr. YOUNG: No. He said I just wanted to thank you for all the things we've

done, you know. We've done some special things together, you know. There's

a--it may sound simple but, you know, things like that, little phrases that

are in the song.

GROSS: Well, it's a beautiful song. Let's hear it. And this is the version

from Neil Young's CD "Prairie Wind." He also performs it in the new concert

film which is called "Neil Young: Heart of Gold."

(Soundbite of Neil Young's "Falling Off the Face of the Earth")

Mr. YOUNG: (Singing) "I'd just like to thank you for all the things you've

done. Thinking about you, I just want to send my love. I send my best to

you, that's my message of love. For all the things you did, I can never thank

you enough. I feel like I'm falling, falling off the face of the earth.

Falling off the face of the earth. Feel like I'm falling, falling off the

face of the earth. Falling off the face of the earth. Falling..."

GROSS: That's Neil Young singing his song "Falling Off the Face of the

Earth." We heard the version on his CD "Prairie Wind." He also performs it in

the new concert movie, "Neil Young: Heart of Gold," which is directed by

Jonathan Demme, who is also with us.

Neil Young, I think of that as a song, you know, although you said that the

song, the idea after the song, came from a Jim Jarmusch phone call. In my

mind, it's a song for your wife. I don't know if there's any truth to that,

but that's how I hear it, when I hear it.

Mr. YOUNG: I agree, I agree. I think that--you know, that's the magic of

songs. That's what it's all about. Everything is connected in one way or

another and the feelings that one person may have, may be, may be when you

write them down and when you sing them, it becomes a completely different

thing. So, you know, that's the magic of art. That's the magic of taking a

picture of something and putting it in a different context with other

pictures, and, suddenly, it means something completely different. And that's

what Jonathan and I do, so, you know, that's just the way that happened. It

is a song for my wife. Obviously, I'm deeply in love with my wife, and she's

the most important person to me, and I was talking to her in the song, but I

was using Jim's words in some cases and couching them in a different frame

work.

GROSS: Then she sings back up in the concert and on the CD. Jonathan Demme,

since you have Neil Young singing and his wife being one of the backup singers

on this, how much did you want to make of that when you were shooting? I

mean, you could, like there's a couple of, like, very meaningful glances they

give each other, but you could have like really made a lot out of this. Do

you know what I mean? You could've, like how did you decide how much to

notice that?

Mr. DEMME: Well, a couple of things. One is that, as far as Pegi Young goes

in the film, one of the things that I really love about the movie is that for

the first several songs, Pegi is part of this preposterously, overqualified

genius backup legion including Emmylou Harris, Diana DeWitt, and that's just

on the female side. And then at a certain point in the movie, later in the

movie when it starts opening up, Pegi comes forward and joins Neil side by

side for a couple of songs there towards the end, and I can't explain why, but

there is just something very beautiful about the movement of Pegi in that

context, and it's kind of thrilling, I think, to see these two side by side

with their guitars, singing these beautiful songs together and certainly

exchanging glances, but, you know, with each other, and they're exchanging

glances with everybody else on stage, too.

When Neil and I first started talking very seriously about doing this film,

which we just always described as a performance film and not a concert film

because we didn't go down there to film a concert, we staged a concert in

order to film it. And, one of the things that Neil talked constantly about in

our early conversations on the telephone was just his tremendous regard and

love for the other musicians, Pegi and Emmylou and Ben Keith and everybody.

He spoke individually about every single person, and he would pepper our

conversations with--you know, Anthony Crawford comes up on that song and, you

know, that's the song that Grant Boatwright plays the electric guitar on. And

I would be scribbling all this stuff down and just really getting very excited

about the possibility of capturing all these strong bonds that exists between

these brilliant musicians on film and making that part of the texture of the

movie.

GROSS: Jonathan Demme and Neil Young will be back in the second half of the

show. I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. We are talking with Neil Young

and director Jonathan Demme about their new performance film, "Neil Young:

Heart of Gold." Most of the songs on it were written last year after Young was

diagnosed with a brain aneurysm, which has since been successfully treated.

The new songs in the film were first recorded on Young's album, "Prairie

Wind." From that CD, here is Young's song "The Painter."

(Soundbite of Neil Young's "The Painter")

Mr. YOUNG: (Singing) "The painter stood before a work, she looked around

everywhere. She saw the pictures and she painted them. She picked the colors

from the air. Green to green, red to red, yellow to yellow in the light.

Black to black when the evening comes. Blue to blue in the night. It's a

long road behind me. It's a long road ahead. If you follow every dream, you

might get lost. If you follow every dream, you might get lost.

GROSS: Let's get back to our interview with Neil Young and Jonathan Demme who

directed Young's new performance film. Demme also made "Silence of the

Lambs," "Philadelphia," and the 2004 version of "The Manchurian Candidate."

One of the things I like about the way you shot this, Jonathan Demme, is that

it's so much about the music and about the emotion behind the music. I think

there really are a lot of, you know, performance films that are about how hip

a band is, about how cool and fashionable they are, about what a good time the

audience in the concert hall was having.

Mr. DEMME: You can forget that.

GROSS: Do you know what I mean? And it's not just about the music itself,

and a lot of camera work is so restless at these things, making you think that

unless the camera is constantly moving and unless there is an edit every

second, that you're going to be bored, and a lot of that sometimes distracts

your attention from the music, and I feel like all the camera work,

everything's done in service to the music and the emotion.

Mr. DEMME: Well, to put even more of a point on it, one of the bottom line

missions here was to make sure that every single lyric, every word of every

song, which in our film kind of functions a little bit like stories--Neil is a

story teller with his songs--we wanted every single word to be just so easily

accessed that nothing would intrude on, just a complete intimate relationship

between the audience and the message that Neil was singing about. And the

other thing was I wanted to make sure that we were up very, very close a lot

of the time on Neil as he was singing these songs so that his emotional state,

as he presented the stuff, was something that we could be very, very akin to.

And I definitely felt that, you're right, stylish camera moves and dolly shots

and crane shots and kinetic editing, all of which I love, and have been used

exceptionally well time and again with music and drama and what have you, but

certainly in the music world. I felt that, you know, none of that stuff would

serve us nearly as well as beautifully composed, beautifully lit--we had Ellen

Kuras doing the lighting, she invented new colors in her artistic

interpretation of what the songs meant to her--nothing could serve us better

than those kind of shots, and I really aspired to find ways and hoped that our

shots played a long time and were not interrupted by an edit to another shot,

unless we had something really worth going to, operating on the premise that,

you know, we're providing the best seat in the house so we don't need to be

cutting around all the time. So, what it all added up to in a way was I felt,

you know, this is kind of bold. It's almost in this day and age where the

family is always moving. Who knows, maybe the fact that we're kind of settled

in a little bit more and don't cut as much might feel kind of avant garde at

this stage of the game.

GROSS: Neil Young, when you went back to the recording studio, after the

procedure to remove the aneurysm, were you in the same mood that you were

before? You know you had had this terrible revelation about the aneurysm, you

had the procedure, you got through it, it seemed to be successful. Were you

in the same frame of mind that you were when you had started writing and

recording those songs?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, now when I shake my head--you know, they put some coils

inside my brain--and now when I shake my head it...(sound of

rattling)...sounds like--just kidding. Cheap shot.

GROSS: So you are not kidding about them...

Mr. DEMME: This is radio, isn't it?

Mr. YOUNG: Hey, come on. This is radio, Bob and Ray.

GROSS: But you are not kidding about coils inside your brain, right?

Mr. YOUNG: No, they're little platinum slinkies.

Mr. DEMME: He was actually shaking his head just then. That was the

darndest thing.

GROSS: But what did they put inside your brain?

Mr. YOUNG: Cheap shot.

GROSS: What did they put inside?

Mr. YOUNG: Little platinum slinkies.

GROSS: And what is the purpose?

Mr. YOUNG: Tiny little slinkies. Well, they're flexible, and they're like,

you know, they're springs, kind of, and they're made out of the thinnest,

smallest, most delicate platinum, and they--you know, they stuffed this thing

full of them. They went in with this, you know, radiology thing or whatever,

they watched it in on TV and they sent this thing up through, you know, from

my leg up through and into my head and packed this little aneurysm full of

these slinkies.

GROSS: And that does what?

Mr. YOUNG: Fooled me. Fooled my body completely. My body thought I had a

bunch of scar tissue going in there, so scar tissue gets more scar tissues. I

think my body filled up the whole aneurysm with scar tissue, and now it's full

of scar tissue, and there is nothing there. The blood just goes flying by

like nothing's wrong.

GROSS: That's really amazing. So...

(Soundbite of rattling)

GROSS: ...be still.

Mr. DEMME: He just scratched his head.

GROSS: My guests are Neil Young and director Jonathan Demme. Their new

performance film is called "Neil Young: Heart of Gold." More after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guests are Neil Young and director Jonathan Demme. Their new

performance film, "Neil Young: Heart of Gold," features songs that Young

wrote last year right after he was diagnosed with a brain aneurysm that has

since been successfully treated.

GROSS: Excuse us, we're having some technical problems. Our interview was

recorded yesterday or earlier this week, and so we're just having a little bit

of problem with our tapes, so we will be back with that interview momentarily

with Neil Young and Jonathan Demme. Their new concert film "Heart of Gold"

opens this Friday in select theaters and in more theaters next Friday.

But I want to play another, like really beautiful song from "Prairie Wind,"

you know, one of the songs you do in the performance from "Heart of Gold." And

this is a song that was written for your daughter, it's called "I'm Here for

You." Would you talk about writing this song?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, this is--this is like, probably the second to last song

that I did before going back to New York, and it's a song about--you know,

it's about my daughter. She's--you know, she's 21 and she's moving on, you

know, she's in college, she's graduating, and I'm really proud of her and how

well she is doing. She's an artist, and you know, of course, I miss her all

the time but I really don't want to intrude so I was just trying to

communicate to her that she has a place to go, but it wasn't a place she had

to go, you know. She--if she needed me, I was there, that myself and her

mother would be there for her if she ever needed us and that she was free to

go and free to stay, and that we were behind her all the way, you know. So it

is just that kind of a song, a kind of letting go without letting go kind of.

GROSS: Well, it's a great song. Here it is. It's "I'm Here for You."

(Soundbite of "I'm Here for You")

Mr. YOUNG: (Singing) "When your summer days come tumbling down and you find

yourself alone, then you can come back and be with me. Just close your eyes

and I'll be there. Listen to the song. This old heart beating for you. Yes,

I miss you, but I never want to hold you down. You might say I'm here for

you."

GROSS: That's "I'm Here for You," a song from Neil Young's latest CD "Prairie

Wind," and he also sings the songs from the CD on his new performance film

which is called "Neil Young: Heart of Gold," and the film is directed by

Jonathan Demme, who is also with us.

You know, the two songs that we just played, this one and the one called

"Falling Off the Face of the Earth," I hear them, and I might be being, like,

overly dramatic here, but they sound to me like the songs that you might have

written as messages to leave behind for the people you love just in case

something happened to you. Am I reading too much into it?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, these songs are meant to be for anything. They're meant to

be for if I'm here or if I'm not here. But all my songs are like that. So, I

really try to write songs like that. I wrote a song years and years ago

called "I Feel Like Going Back," and it could have been one of these songs,

and, you now, it's all about not one particular time or place or situation but

the whole thing. I try to make it so that it will work, you know, that's

where I'm coming from, so it will work no matter what happens.

Mr. DEMME: This movie ends with "One of These Days" which Neil wrote years

ago and reinterpreted for the movie, but that's as rich and, you know, as

emotionally powerful a summing up song as any other song on the "Prairie Wind"

album, I think.

GROSS: Are there things that you think were easier to say in a song than in

conversation?

Mr. YOUNG: Oh, yeah. Yeah, on practically everything. Actually, yeah, but,

you know, I really, I'm glad that I can write songs because I would've

probably gone crazy by now if I couldn't have put some of these ideas down in

a way that is obscure enough so you can say them at any time, and yet, when

you hear it, if you are thinking about it and you are wide open to it, then

you can go a lot farther than the current conversation.

GROSS: How did you both decide which songs to include in the performance

from, obviously, you have the songs from "Prairie Wind," but there are also

earlier songs, early Neil Young songs on there and you obviously had a lot of

songs to choose from. So, how did you decide which ones you wanted to

include?

Mr. DEMME: Well, "Prairie Wind" was all I cared about when we started making

the movie. It was it. Just that suite of songs was, as far as I'm concerned,

just a perfect amazing body of work unto itself. And we were pretty far down

the line, you know, we knew we were going to go to the Ryman. We knew that

Manuel was going to do the costumes. We knew that Michael Zansky was going to

do the backdrops. We knew that Andy Keir was going to cut it and Alan was

going to shoot.

And then I was in my kitchen one day, and I suddenly went, `Wait a minute,

we're going to have a 55-minute movie.' So I called Neil up and said, really

pretty crude, I just said, `You know, if we only have 55 minutes and we're

hoping that we can get this film into movie theaters, would it be possible to

add an encore dimension to kind of rough out the running time, to flesh out

the running time?' And Neil right away said--I felt funny asking him that, but

I did. And then he said right away, `Sure, let me think about it. Obviously,

I'll have to draw from my Nashville body of work pretty much.' And he also

said he wanted to think about it and select songs that would be thematically

compatible with the songs of "Prairie Wind."

So, you know, off he went. And then we saw each other a little while later,

and Neil had created a list of songs. And he showed them to me, and it was

basically the songs that are in the movie and a couple of others. And it is

such a treasure trove.

But the funny thing for me is that I was so focused on "Prairie Wind" and my

love for those songs that--and I thought that's terrific that our film will

end with some wonderful of the earlier songs. But I had no idea that those

earlier songs were going to wind up packing such a tremendously strong

emotional wallop.

GROSS: Well, the effect that you have with some of the olds songs, you know,

the effect I think that it registers on me, anyway, and the audience is that

here you have some of the songs, Neil Young, that you wrote and recorded when

you were a young man, and some of these are about age. And now you're singing

them as, you know, someone who isn't a young man. I think you're, what, 60

now?

Mr. YOUNG: Yeah.

GROSS: And so the songs...

Mr. DEMME: What's so old about that?

GROSS: And so the songs, they have a different resonance. They have a

different meaning. And, you know, and the audience like you feel you almost

reflecting on the songs and how the sound of the songs have changed. Do

you...

Mr. YOUNG: Well, there's a trick in there.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. YOUNG: To interrupt. Sorry to interrupt you. But what really happens

with these songs is--I think is that the whole beginning of the film we're

singing songs that have never been heard by the audience that we're singing

them for. And they are all brand-new, so they are firsttime presentations of

the songs, which makes you listen and you open up and start listening to

something because you don't know what it is. And you're seeing it in a way

that you've never seen anything from me before. So you're seeing them in a

new way and you're listening to new songs that are being done for the first

time. So it really opens you up. So what happens when we get to the second

half is that the audience is totally open to new material and listening to the

words and trying to pick up on everything that these songs are saying because

you only had one shot to pick up on it.

And when we go into the second part of it, it's basically a chronological trip

through my music, with a few departures from chronology. But it is starting

back in Buffalo Springfield and going through to, I guess, "Harvest Moon"

or--yeah, "Harvest Moon." So it goes through that. But the thing is, you

listen to it a lot more than you have been. Instead of celebrating, `Hey,

there's another old song and he's doing these songs that I like,' you're not

doing that. You're still listening because you've been tuned into listening

in the beginning and listening for the words. So they become part of the

story because you're trained and you have trained yourself to listen instead

of just watching and celebrating these old tunes that you've heard before.

You're listening to them like they're new tunes. And so I think that opens

the door for people to go on the journey with the songs.

GROSS: My guests are Neil Young and director Jonathan Demme. Their new

performance film is called "Neil Young: Heart of Gold." More after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guests are Neil Young and director Jonathan Demme. Their new

performance film, "Neil Young: Heart of Gold," features several classics, as

well as new songs that Young wrote last year right after he was diagnosed with

a brain aneurysm that has since been successfully treated.

The songs in the movie, the takes are all so good that you almost feel like,

`God, it must have been post-dubbed or something because no concert goes this

smoothly.' You know that with like note-to-note perfection.

Jonathan Demme, how many takes were there for each of the songs? How did you

manage to get such good takes?

Mr. DEMME: Well, we didn't do takes per se. The concert was performed two

nights in a row, August 19th and August 20th. And the curtain parted and the

music was there. In fact, the music started before the curtain parted. And

we didn't redo any of the songs. We filmed them on both nights, and then

later we were able to either select which night seemed to be the better of the

two excellent performances. Because, frankly, each night was unbelievably

great. And everyone once in awhile, we did a sort of combination of the two

nights.

And in one instance, in "Old King," which is a song I love. I got so carried

away that, with Neil's permission, we actually made that longer and stretched

out the instrumental part of that so we could really just let the audience

just--something about everybody up there doing that kind of what I call a

hoedown. And Emmy Lou Harris strumming amazing guitar, and Neil rocking out

on the banjo and what have you.

And so that was it. We didn't do any retakes. You have to realize that the

amount of preparation for Neil and his fellow band members that preceded the

show, they rehearsed for 10 solid days straight ahead. Like Neil said

earlier, everybody knew that they were introducing the "Prairie Wind" songs

for the very first time. No one out there ever would have heard these. The

CD hasn't come out yet. It was going to be a brand-new experience. And I had

the unique thrill of presenting it for the first time on the stage at the

Ryman Auditorium in Nashville to a audience that had been largely invited and

was made up of songwriters and musicians and people who just adore the kind of

music they were about to hear.

So everybody was just at their peak form. And, you know, we just got the

cameras in focus, and they let it rip. And it was quite an exquisite night of

music.

GROSS: Neil Young, one of the things that adds to the emotional depth of the

movie is that onstage, before introducing one of the songs that has to do with

your father, you talk about how he had recently died after having dementia for

10 years. And you talk about how interesting it was to watch him living in

the moment. And I thought that's the kind of positive thing to find about

somebody who has dementia is that they're living in the moment. Did you hold

on to that as a way of seeing something positive about his dementia and his

inability to remember the past?

Mr. YOUNG: Well, I just focused on what his life was about now and not what

it was about, you know, used to be about. Just more because the love is still

there and everything, but I couldn't think of any other way to describe it.

GROSS: Mm-mmm.

Mr. YOUNG: Because that's really all that I think was left. I just--I don't

know. Perhaps it was easier for him to remember things than it was for him to

speak about what he remembered. So I don't know the connection. I don't know

whether people with dementia actually can't remember anything or whether they

can't put the words together to explain what it is. Because just putting a

sentence together takes an incredible amount of reasoning power in the

present. And it really, we take it for granted, and we speak along and it's

quite a creation, the human body, that enables us to think and talk and do all

of these things at the same time. So as it slowly breaks down and the

connections get lost, it's kind of hard to say exactly where things are and

what's happening. But I know that my dad was living in the moment so I use

that phrase to describe what was going on. That's the best I could do.

GROSS: Do you feel right now that you're--there is something very cathartic

about the performance film? Do you feel like you've come through the other

end of something by having kind of lived through the whole aneurysm thing,

written the songs you wanted to write, recorded the CD, done the performance

film. They are both really emotional kind of experiences. Do you feel like

you're out the other end of something?

Mr. YOUNG: I feel like I'm at the beginning of something else now.

GROSS: Of what, do you know?

Mr. YOUNG: No. But I know I'm at the beginning of something. And nothing

ever really ends with music. It just keeps on going on. It's like it's an

eternal exhaust out of some, you know, interplanetary spaceship. It just

keeps going, you know. It's just out there. Anything you put out just keeps

on happening. People could listen to this music in a hundred, 200, 300 years

from now as far as I know. So what we do now lasts forever. And what we're

going to do next is what matters.

GROSS: Jonathan Demme, one last question for you. When you were making this

movie, did you dream these songs every night? Were you hearing them so much

and thinking about them so much that they just like stuck with you even when

you should have not been thinking about them, like when you should have been

sleeping?

Mr. DEMME: I'll tell you, all my three children worked on the movie with me,

each in different capacities. And my wife Joanne was there. And all I can

tell you is that everybody is obsessed with these songs, and we'd no sooner

come home from, you know, 12-14 hour rehearsal sessions, and we'd come home

and somebody or other would put the CD on. So we lived "Prairie Wind"

throughout the shooting and driving in the cars on the weekends playing it.

And, finally, we all were able to sing all the lyrics to all the songs. So it

got very obsessive. Yes.

GROSS: Well, I want to thank you both so much for talking with us. Thank

you.

Mr. DEMME: It was fun, Terry. Thank you.

Mr. YOUNG: Thank you.

(Soundbite of rattling)

Mr. DEMME: That was Neil getting up.

GROSS: Neil Young's new performance film, "Heart of Gold," was directed by

Jonathan Demme. It opens Friday in select cities and in more cities next

week.

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross. We'll close with another song from "Prairie Wind"

that's also featured in Neil Young's new film.

(Soundbite of Neil Young singing)

Mr. YOUNG: (Singing) "Was he thinking about my country or the color of my

skin, was he thinking about my religion and the way I worshiped him? Did he

create just me in his image or every living thing?

Mr. YOUNG and Backup Singers: (Singing) "When God made me, when God made

me."

Mr. YOUNG: (Singing) "Was he..."

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.