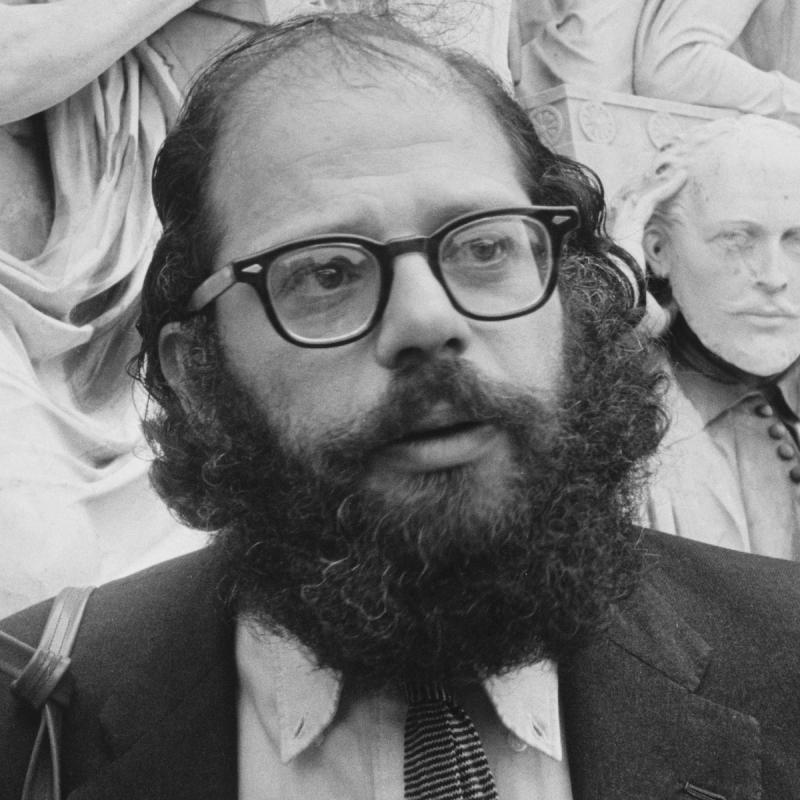

Cultural Heroes and One-of-a-Kinds: Poet and Countercultural Activist Allen Ginsberg.

The late beat poet and countercultural activist Allen Ginsberg. He died in 1997. There's a four-CD boxed set of Ginsberg's work, "Holy Soul Jelly Roll -Songs and Poems (1949-1993) (on Rhino's Word Beat label).(REBROADCAST from 11/8/94)

Other segments from the episode on October 19, 1999

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: OCTOBER 19, 1999

Time: 12:00

Tran: 101901np.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Archive Interview with Allen Ginsberg

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:06

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

This week, we're presenting a series of interviews with cultural heroes and one-of-a-kinds.

The late Allen Ginsberg was a cultural hero to several generations. He was one of the leading beat poets in the '50s. In the '60s, he was a cultural icon of the counterculture. Through the '70s and '80s, he continued to write and to explore Eastern religions. By the '90s, he was an inspiration to up-and-coming performance poets.

Allen Ginsberg died of liver cancer in 1997 at the age of 70. His work is being revived in several forms. A new book about him, called "Screaming With Joy," has just been published. Archive footage of him is featured in the documentary about beat writers, "The Source." And several collections of his poems and essays will be published over the next few months.

We're going to hear an interview I recorded with Allen Ginsberg in 1994. Let's start with an excerpt of his 1956 recording of his now-classic poem, "Howl."

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, "HOWL," ALLEN GINSBERG)

I saw the best minds of my generation

Destroyed by madness

Starving, hysterical, naked

Dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn

Looking for an angry fix

Angel-headed hipsters

Burning for the ancient heavenly connection

To the starry dynamo

And the machinery of night

Who poverty and tatters and hollow eyed and high

Set off smoking in the supernatural darkness

Of cold-water flats

Floating across the tops of cities

Contemplating jazz

(END AUDIO CLIP)

GROSS: "Howl" was partly inspired by Allen Ginsberg's mother, who had been in a mental hospital.

(BEGIN AUDIOTAPE)

ALLEN GINSBERG, POET: She had been there for several years, and I had put her there after a breakthrough, some very violent behavior toward her sister and a cousin she was staying with. And I had gone out to San Francisco, but the grief was very much on my mind. I had a friend called Selverman (ph) with whom I had been in a mental hospital six years before, and he was back also in Pilgrim State, too.

So I addressed the poem ostensibly to him, but the emotions were, I think, directed toward my mother, both grief and a sense of solidarity.

GROSS: Yes, you know, Part One begins with one of your most famous lines.

GINSBERG: Yes.

GROSS: "I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness."

GINSBERG: "Starving, hysterical, naked." The original phrase was "Starving, mystical, naked," but I figured that was a little bit too simple-minded, because the problem was not all -- the problem was society, it was also the neurosis of the people. So there's a certain ironic edge to it which I don't think critics at the time realized. I said, "Starving, hysterical, naked." So it wasn't just a one-dimensional protest for the safety of madmen, you know. It was also, like, trying to give quick sketches of a series of cases that I drew from real life.

GROSS: Now, I want to move on to another poem, "America," that was read the same night as "Howl," I think, was that -- at the same reading.

GINSBERG: Yes, and that's the very first unveiling of that poem. It was really funny. The text in the recording differs a little from the final text that I wound up with. There are a few extra and some very funny lines, actually.

GROSS: Yes, it really is very funny. You get a lot of laughs from the audience.

GINSBERG: Well, it sounds like a stand up comedy routine. That's the era, actually, of Lenny Bruce around San Francisco. He was playing, I think, at the Purple Onion. And I went down to see him and watch his act, actually. But I hadn't expected that kind of reaction.

And I didn't think the poem was that good, nor did Kerouac. It was just sort of like a joke, or, you know, like a takeoff, send-up of America, very lighthearted. But it's done with many different voices in a kind of schizophrenic persona -- you know, one minute serious, one minute faggoty, one minute desperate, one minute religious, one minute patriotic, one minute I'm putting my queer shoulders to the wheel.

GROSS: Why don't we hear the beginning of "America" as you read it in 1956 at Town Hall in Berkeley?

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, "AMERICA," ALLEN GINSBERG)GINSBURG:

America, I've given you all and now I'm nothing.

America, two dollars and twenty-seven cents, January 17, 1956.

America, I can't stand my own mind.

America, when will we end the human war?

Go (bleep) yourself with your atom bomb.

I don't feel good. Don't bother me.

I won't write my poem till I'm in my right mind.

When will you be angelic?

When will you take off your clothes?

When will you look at yourself through the grave?

When will you be worthy of your million Christs (ph)?

America, why are your libraries full of tears?

America, when will you send your eggs to India?

I'm sick of your insane demands.

When will you reinvent the heart?

Where will you manufacture lambs?

When will your cowboys read Spengler?

When will the dams release the flood of eastern tears?

When will your technicians get drunk and abolish money?

When will you institute religions of perception in your legislature?

When can I go into the supermarket and buy what I need with my good looks?

America, after all, it is you and I who are perfect, not the next world.

Your machinery is too much for me. I don't want to work for a living.

You make me want to be a saint.

There must be some other way to settle this argument.

(END AUDIO CLIP)

GROSS: You know, you must have seen yourself as a provocateur, in a way, at a very young age. I'm thinking, you know, that you were just coming from a place that was not average. You know, your mother was mentally ill, your mother had been a Communist. You were gay. You were an intellectual. You loved poetry. I mean, just...

GINSBERG: And also...

GROSS: ... everything about your life kind of set you apart.

GINSBERG: But you got to realize, by this time I had already known William Burroughs and Jack Kerouac 12 years. This is not, you know, some sudden...

GROSS: Right.

GINSBERG: ... discovery of community or ideas. We had had a long period of privacy and silence to ripen our art, to know each other, and to amuse each other, and to understand each other's language and intelligence and sort of enlarge our own consciousness with the experience of others.

Also, I'd already had some sort of natural religious experience, and we had all by this time tried out some of the psychedelic drugs, in addition, on top of a natural religious experience that was without drugs. And already had traveled a bit.

And so we were -- I wasn't a young kid then, I was 28 years old. You know, it was quite a ripe time.

GROSS: Was it surprising to you to find people like Burroughs and Kerouac who you felt this kind of friendship and aesthetic closeness with?

GINSBERG: No, it was just some sort of natural kinship that we felt, almost instantly on meeting.

GROSS: But did you expect you'd ever find that?

GINSBERG: Not exactly. But I hadn't even conceived of such a thing. I conceived of friends, and I'd had friends in high school. But I was still in the closet. Kerouac was the first person that I was able to come out of the closet to and tell him about it, and actually slept with him once or twice, though he was primarily straight. But he was very tender toward me, and he saw that I was in solitary and in a great deal of confusion and anguish, and he took a sort of kindly view.

Burroughs was always out front and clear and lucid and intelligent, as he is now at the age of 80. He was so at the age of 34, I think he was then.

So I was lucky when I was 17 that I met people whose genius sort of ignited my own talents to -- and sort of upgraded, I think, my own natural intelligence. But I'm really a student of Kerouac and of Burroughs, and in some respects an imitator. I've had a steadier life, and so I'm perhaps more on the scene, as now, on the air, going around giving readings.

But I feel myself basically a pupil of Kerouac's here in his intelligence and language and his awareness of the pronunciation of consonants.

GROSS: But when you talk about being a student of Kerouac's, I've never been able to tell how much your style of reading influenced him, and how much his style of reading influenced you.

GINSBERG: Oh, I think his style influenced me. It was way back in '47, '48, I heard him read Shakespeare aloud, and it was such an interesting intonation that he put into a soliloquy of "Hamlet," I think, where Hamlet is sitting down on the steps saying, What am I, you know, what am I doing? Am I nothing but a John-a-dreams? The way Kerouac said that, "John-a-dreams."

It was like his mind went off into a little dream in that phrase.

So I began seeing that there was -- there were intonations, differences of pitch possible. You know, most poetry was -- still is pronounced in a monotone or duotone, where you -- you know, just like I'm talking now in a sort of monotone. But there are possibilities in conversation where you go from, you know, a little high woodle (ph) when you're talking to a little baby, to down to very serious heart tones, when you're talking to your grandmother on her last days on earth.

GROSS: Of course, with your readings, I always felt that there was a certain Hebraic intonation, even though I know that, you know, Buddhism was probably an even greater influence on you. And you certainly...

GINSBERG: No...

GROSS: ... hear that in your voice, too. But there is that kind of Hebraic sound.

GINSBERG: The Hebraic thing is very real. My grandfathers were rabbis, and one of the most strong musical influences I ever had was hearing a recording of Sophie Breslau, a great operatic singer, singing "Eli, Eli" (ph), with a kind of melismus, I guess you'd call it, sort of a very beautiful way of bending the notes that's characteristic of Hebrew melody.

GROSS: Now, when did that start to enter your reading style?

GINSBERG: Well, certainly with "Kaddish," because I was imitating the davening (ph) motion of Kaddish, where the -- you know, the sound of "Ysh kada, ysh kada, ysh aleh, ysh alo, me kushu gel (ph)" -- da-da-dah, da-da-dah, da-da-dah. Magnificent, "More no more martyr of heart, mind behind merry dream, mortal changed (ph)."

That is -- the whole rhythm of the poem has a kind of combination of Ray Charles, "I got a woman, yes, indeed, yes, indeed, yes, indeed," and -- which I'd been hearing the afternoon -- the morning before I wrote the poem, and the rhythm of the original Hebrew Kaddish that was still running through my mind and body. First time I'd heard it, actually. A Jewish friend played it to me in dawn light the morning that I started writing the poem.

GROSS: And the Kaddish is the Hebrew prayer for the dead.

GINSBERG: Yes, it's kind of mass or prayer for the dead done in the synagogue when you have a minyan, or a group of elders that are -- can get together to help you mourn for the dead.

GROSS: So I guess you didn't say the prayer when your mother died.

GINSBERG: Well, I didn't know it as well. But I did try and do it. Actually, I wandered around San Francisco with Jack Kerouac and Philip Wayland (ph), and we went into various synagogues. But there was no minyan, so that we couldn't do it. So this is a way of making up about a year, couple years later.

GROSS: And this is a couple of years after your mother, Naomi, died.

GINSBERG: Yes, my mother died in '55. Incidentally, you know, I sent her the original -- a copy of the original manuscript of "Howl," which she received about a week before she died, and she wrote me a letter which was postmarked the day she died, which is quoted in "Kaddish," in which she said she got my poems. She can't tell whether it's good or bad. My father should judge, because he's a poet. But judging from the -- that I should -- She'd read it, obviously, she said, "Get married, Allen, and don't take drugs."

And she said, "I have the key. The key is in the window. The key is in the sunlight in the window." And then she died of a stroke, I think, perhaps hours or within 24 hours of writing the letter.

So I received that letter after I'd heard that she died. So it was like a message from the land of the dead, so to speak.

(END AUDIOTAPE)

GROSS: Allen Ginsberg, recorded in 1994. He died in 1997 of liver cancer at the age of 70.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

GROSS: Let's get back to our 1994 interview with poet Allen Ginsberg, he died in 1997.

(BEGIN AUDIOTAPE)

GROSS: Now, if you had grandfathers who were rabbis -- did you say?

GINSBERG: Well, scholars, you know, long guys with big black hats and long gray beards, and died of cancer from smoking actually...

GROSS: But, how did...

GINSBERG: ... in New York, in the '30s.

GROSS: ... How did you get to be in your 20s before you heard the prayer for the dead?

GINSBERG: Well, we didn't -- my mother was communist and my father was socialist.

GROSS: So, you didn't go to synagogue?

GINSBERG: So, I did go to synagogue, and I went to -- what, Sunday school, or what to you call it, the schule (ph), to learn Hebrew and traditional -- prepare for a bar mitzvah, but somehow I asked questions that were resented by the rabbi and I got kicked out when I was about eight years old or nine.

And I never did understand it because I thought I was just sort of talking intelligently to them and inquiring. But there must have been an edge of skepticism to it, but there was no tolerance for that at all. My questions weren't answered and I was just told to get out. So, I've never had very much of a classical Hebrew education.

GROSS: Your mother was institutionalized several times.

GINSBERG: Many, many times, all during my childhood. I'd go out to visit her in Greystone Hospital.

GROSS: Were you frightened by her madness?

GINSBERG: Sometimes, sometimes sorrow, sometimes frightened, sometimes stuck with a responsibility I couldn't carry out as a kid. Going out alone to see her in a mental hospital when I was 12, 13, 14, was a -- or having to stay home and take care of her while my father was in school teaching, and getting into crisis situations with her that I couldn't handle, actually, it kind of broke my brain in a way. It broke my spirit to some extent.

GROSS: Now, when you started doing hallucinagenics like LSD, did your hallucinations ever scare you because you'd seen your mother have hallucinations and delusions because of her mental illness?

GINSBERG: Well, no, not really. I realized that if everybody began disagreeing with me, I better look around twice, and think three times, and be pretty sure I knew what I was doing. And so, I have been able to be in situations where everybody disagreed, but at the same time maintain my sanity, so to speak, by simply following my heart, really. I have as much a tendency to paranoia as anybody in the United States at this point, but at least I can see it's paranoia, and most people don't see their own paranoia.

GROSS: That's interesting. So your mother's delusions actually helped you figure out what was real and what wasn't?

GINSBERG: No, I went through the -- Yes, I sort of went through the mill already, so I was kind of inoculated.

Yes, I would say that the experience of having to deal with somebody who was sort of deluded and hallucinating, also voices and all; helped me deal with my own psychic disturbances and also with the psychic disturbances of other people. I seem to be -- have a kind of tolerance, you know, in one ear out the other, or, you know like -- so that I can be with people who are quite disturbed. I get disturbed myself but not so much so that I have to turn my back until, you know, all hope is lost.

GROSS: Where were you in your performance style in 1964? The years that the recording of Kaddish was made?

GINSBERG: I hadn't ever tried to read anything as long as Kaddish, complete. And so there -- and I had drunk a little bit, not very much so I wasn't really drunk, but I was sort of a little keyed up with alcohol so that I was able to loosen my feelings quite little bit. So, the only problem there is maintaining control of feelings and not breaking up and crying in the middle of more moving passages.

GROSS: Is there a particular section of Kaddish that you've had the most problem with; controlling your emotion?

GINSBERG: Yes, the last time, and I walk in and I see she's had a stroke. Then suddenly there's a break in the poem and there's a kind of lyrical rhapsody: "Communist beauty six-year married in the summer among daises promised, happiness at hand."

It's a section that ends: "Oh beautiful garble of my Karma."

It's really a nice, exquisite, poetic passage, and it's also full of feeling and it's like a flashback in the midst of tragedy, to a happier day, so there's a lot of emotion buried there from childhood.

Also, at the very end, the section: "Oh mother, what have I left out. Oh mother what have I forgotten. With your eyes. With your eyes. With your death full of flowers."

That has a sort of cumulative emotional buildup and -- that's quite great.

GROSS: Why don't I play an excerpt of Kaddish, and you wrote this in the late 1950s. The recording we're going to hear from your new box set was made at Brandies University in 1964.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, "KADDISH," ALLEN GINSBERG)

GINSBERG:

With your eyes running naked out of the apartments, screaming into the hall.

With your eyes being lead away by policemen to an ambulance.

With your eyes strapped down on an operating table.

With your eyes with the pancreas removed.

With your eyes of appendix operation.

With your eyes of abortion.

With your eyes of ovaries removed.

With your eyes of shock.

With your eyes of lobotomy.

With your eyes of divorce.

With your eyes of stroke.

With your eyes alone.

With your eyes.

With your eyes.

With your death full of flowers.

(END AUDIO CLIP)

GROSS: That's Allen Ginsberg reading an excerpt of Kaddish, it's included on his new box set, "Holy Soul, Jelly Roll."

Tell us just a little bit about what your life is like now.

GINSBERG: Well I have a little heart trouble and diabetes, but I travel a bit still, and I write quite a bit and I'm doing a lot of photography, and have put out several books of photos, and so I have -- and now this year I think I'll do some doodles, and sort of start drawing. So, you know, just enjoying myself at the age of 68, extending my activities in various directions but focused primarily on writing and on poetry. With the idea that candor ends paranoia. If I can make my own mind transparent, so that people know what I'm really thinking; they don't have anything to be scared of and they can use it as a mirror for their own minds.

(END AUDIOTAPE)

GROSS: Allen Ginsberg, recorded in 1994, he died in 1997 of liver cancer at the age of 70.

Several new collections of his poems and essays will be published over the next few months and there's a new book about him called, "Screaming with Joy."

I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia, PA

Guest: Allen Ginsberg

High: The late beat poet and countercultural activist ALLEN GINSBERG. He died in 1997. There's a four-CD boxed set of Ginsberg's work, "Holy Soul Jelly Roll -- Songs and Poems (1949-1993) (on Rhino's Word Beat label). (REBROADCAST from 11/8/94)

Spec: Art; Entertainment; Poetry

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1999 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1999 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Archive Interview with Allen Ginsberg

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: OCTOBER 20, 1999

Time: 12:00

Tran: 101902NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Archive Interview with Artist Chuck Close

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:30

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Our faces reveal so much about who we are. That's part of what makes Chuck Close's paintings so fascinating. They offer you the chance to stare at larger-than-life, hyperrealist renderings of faces, faces that become transformed into what "Time" magazine art critic Robert Hughes described as "moonscapes of pores, wrinkles, blackheads, and stubble."

Chuck Close doesn't paint with big, elaborate brush strokes. His faces are composed of little dots, circles, and squiggles. It's the accumulation of these markings that add up to the larger image of the face.

Chuck Close has been painting faces since the '60s. It's amazing that he can paint at all now. Nearly 10 years ago, a stroke left him paralyzed from the neck down. After a partial recovery, he's been able to paint from his wheelchair.

I spoke with him last year after the opening of a retrospective of his work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. I asked Chuck Close why the face has been his subject for so long.

(BEGIN AUDIOTAPE)

CHUCK CLOSE, ARTIST: Well, initially I started making portraits -- or at that time I didn't even call them portraits, I called them heads -- because it was as different as possible from what I had been doing before. My work had been abstract, and I was looking for something that was diametrically opposed to what I had done as a student.

And so the first heads were just my friends, and I had no idea then, 30 years ago, that I would still be painting heads today. And, in fact, I'm sure I wouldn't have believed it if somebody had predicted it.

But over the years, I found that of all the kinds of subject matter that I could use, nothing interests me as much as people, and it offers the viewer an entrance into the work through life experience, because we all look in mirrors and look at each other and look at images in magazines and film.

And it's a great leveler, whether a person is the most sophisticated person in the art world or a layperson, we all share that knowledge of an interest in the way people look.

GROSS: I want to talk a little bit more about the faces themselves, the way you paint the faces themselves. You've said that you try to see the faces neutrally, without opinion or subjectivity, without editorializing in any way about the face. And yet the face always reads in some way to me. I see the faces very subjectively, even though you as the painter didn't see them subjectively.

Talk with me about the approach that you're taking toward this subject matter, of not kind of imposing any kind of feeling or point of view.

CLOSE: Well, it's not that I'm uninterested in the psychological reading of the paintings. I just don't want to lobby for one reading over all others. And to present them straightforwardly and flatfootedly without editorial comment, without cranking it up for extra psychological readings, or without drawing big circles around things, saying, make sure you see it this way.

I sort of leave it to the viewer to, you know, to read the image. And I believe that a person's face is a kind of road map to their life, and embedded in the imagery is a great deal of evidence if you want to decode it. If a person has laughed his or her whole life, they'll have laugh lines. If they've frowned their whole lives, they have furrows in their brow.

And it's not necessary for me to have them laughing or crying or anything in order to have people be able to read them.

GROSS: Your canvases are very large. And because you include every detail of a person's face, every line and wrinkle and pucker and pore, every flaw is included, or what we'd consider a flaw is not included, but it's kind of enlarged, because the painting is so large.

And that's part of what I find so fascinating. The faces are so real and recognizable, looking at one of your faces in a painting, it's a lot like looking at yourself in the bathroom mirror with the kind of harsh lighting that you have there. And you see everything.

So there's something so recognizable about the landscape of the faces, the way you paint them.

CLOSE: Well, yes, I -- we don't stand close enough to each other, we don't invade each other's space enough to really be able to see the intimate level of detail that I typically put in one of these paintings, because they're in fact usually nine feet high.

So if there's more information than you ever really wanted to know about someone, and it makes it perhaps a more intimate experience.

I make these -- try to make these big, aggressive, confrontational images that you can see for clear across the room, and you have one kind of relationship with it there. And then another relationship at a middle viewing distance, where you scan it and you can't readily see the thing as a whole. And then hopefully I've sucked the viewer right up to the canvas, where you can see the individual marks and the methodology, how I got there.

GROSS: Now, tell us a little bit about the way you work with grids when you're painting a face from a photograph.

CLOSE: Well, grids, you know, besides being one of the great modernist conventions, the grid has been around most recently because it's a flattening device. It's a way to, you know, to restate the flatness of the canvas. But in fact, the use of a grid as a scaling-up method goes back to ancient Egypt and was, of course, used in the Renaissance and used all along as a way to take a small drawing or preparatory sketch and enlarge it, by having smaller squares on the preparatory sketch and bigger ones on the painting.

It's just a way to scale up an image. But at a -- and all of my work, from the 1960s on had been built with the use of a grid. I don't use a projector or anything like that to get an image on. But at a certain point I decided to let the grid remain a visible part of the image. Initially I would get rid of the grid so nobody knew that I used it. But at a certain point, I began to leave the incremental unit to show, and I found all kinds of ways, from using my own fingerprints to gluing on little wads of pulp paper to any one of a number of ways of working incrementally, and letting the individual unit show.

One of the things I like about working that way is that there's nothing about the building block which says anything about what's going to be made from it.

GROSS: Exactly, right, exactly.

CLOSE: There's no mark that equals hair, there's no mark there equals skin or anything else. It's a little bit like an architect choosing a brick. The brick doesn't determine anything about what kind of building will be built from it. You stack up the bricks one way, and you make a gas station, or you stack up the bricks another way and you can build a cathedral. Both of them will be very different experiences, but it wasn't the brick that determined the nature of that experience.

GROSS: So what suits your personality about working in these smaller units, one dot at a time or one grid at a time?

CLOSE: Well, you know, actually I'm a nervous wreck. I'm a slob. I'm -- I have no patience. And I'm rather lazy. All of those things would seem to guarantee that I would not make work like I make. But I felt I didn't want to just go with my nature and say, Well, that's the way I am, I can only make big, sloppy, nervous, quick paintings.

I thought to construct a situation in which I couldn't behave that way was also to address my nature.

But I found that one of the nice things about working this way, working incrementally, is that I don't have to reinvent the wheel every single day. Today I did what I did yesterday and tomorrow I'll do what I do today. You can pick it up and put it down. I don't have to wait for inspiration. There are no good days or bad days. And I'm -- every day essentially builds positively on what I did the day before.

In some ways, I think it's rather like what used to be called women's work, that is, quilting, crocheting, knitting, or whatever. And the advantage of that way of working was that women could knit for a while, put it down, go feed the baby, come back and pick it up and knit a little more, and then put it down and go out and weed the garden. And it was -- it allowed for a way to just keep working.

If a belief in a process -- for instance, how do you make a sweater? Oh, my God, I wouldn't know how to make a sweater. But if you believe in the process and you knit one and you purl two long enough, eventually you get a sweater.

And I think given my nature, it was very good for me to have a way to work in which I was able to add to what I already had and slowly construct the final image out of these little building blocks.

GROSS: How have you dealt with impatience, though? Don't you ever feel like, OK, it's going to take me another 12 months of these dots to have a painting. I want to see it now.

CLOSE: Well, you know, that's -- I do finish each area as I go, so I have a chance to see what it's going to look like almost from the beginning. But, you know, patience is a funny thing. I used to work every day and make a painting every day. And now I work every day and I make a painting every several months. But work is work, and it doesn't seem to take any more patience to keep working on one piece than it did to make a different piece every day.

And the big difference is that I used to enjoy painting, I loved the activity, but I didn't care very much about what I made. And now I have a way of working which, like I say, is essentially positive building on what I already have, and eventually I get to something about which I care a great deal more.

So for me, that was a very productive tradeoff.

GROSS: My guest is painter Chuck Close. We'll talk more after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

GROSS: My guest is painter Chuck Close. We're going to hear about a medical condition that transformed his life and nearly ended his career.

It was, I think, 10 years ago that you had a terrible medical problem. I think it was a blood vessel in your spinal cord that -- that what, that broke, and...

CLOSE: Well, actually it's very funny that -- I don't whether know the listening audience knows that you're in Philadelphia and I'm in New York, and I'm staring at a microphone instead of staring at you. But it is -- it was nine years ago that I was in this very studio talking to Susan Stanberg (ph) about the National Endowment for the Arts, which was the last thing I did before I went up to Gracie Mansion, where I in fact became -- suffered this collapsed spinal artery and became, within a matter of a few minutes, a quadriplegic.

So it's a little freaky to be in this studio, and I'm sort of wondering about what's going to happen today when I leave.

But at any rate, yes, I did have this event in my life in which I ultimately became a -- what's called an incomplete quadriplegic. I'm -- I was initially paralyzed from the shoulders down, but I got considerable return, and I don't have the -- I am confined to a wheelchair, and I don't have the use of my hands. And I paint now with brushes strapped to a brace, which is strapped to my arm.

But essentially, I'm not doing anything that I don't think I would have been doing anyway. I think the work has progressed much the same way that it would have. And luckily, I had something to get back to that really mattered to me. If I hadn't already known how to paint, I don't think I could have learned to do it post-injury.

But once you know how to do something, it's not so hard to equip yourself with what's necessary to be able to get back to it.

GROSS: Because you don't have much movement now at all, and you have to paint with the brushes strapped onto your wrist, have you given a lot of thought to how much painting is something that happens in your mind, and how much is something that happens with your hands?

CLOSE: Well, somebody told me in the hospital, and I don't remember who it is, that, Oh, you'll be all right, because you paint with your head and not with your hands. And I thought, Oh, easy for you to say!

GROSS: (laughs)

CLOSE: I thought, Gee, this is like something that came out of a fortune cookie or something. I was actually quite annoyed that they had this kind of throwaway answer for my very severe problem.

But in fact, you know, they were right. Once you know what art looks like, you can figure out how to make some of it. And it's just a question of adaptation.

I would like to say also that part of my ability to get back to work is largely due to the fact that I am and have been for 30 years a very successful artist and have made a lot of money, and I can afford to equip myself with what's necessary to be able to get back to work. I can have a totally wheelchair-accessible studio. I can hire assistants who can get me where I want to go.

And I still make the paintings entirely by myself. My assistants don't help me paint. But they help me with all the other things.

So if this were to happen to another artist who was not as recognized and celebrated as I was, and not as financially successful as I was, no matter how much they might have wished to get back to work, it may have been an impossibility.

So again, I think that I'm very lucky.

GROSS: If you don't mind my asking, I know -- you know, often when people lose the ability to move, it's through a traumatic accident, a car crash, or, you know, some kind of terrible injury, a fall. But for you it was a broken artery, and so...

CLOSE: I just sort of collapsed.

GROSS: Yes. So did -- when did you realize that you had lost movement? Did you awaken from a coma, or was this something that came on gradually?

CLOSE: Well, I had tremendous pain, and I had to have -- I had had the pain over the years. It would come and go. And nobody could ever figure out what it was. And this time, the pain ended up -- I had sort of massive seizures all over my body, and then all of a sudden, I just -- my whole body just was still. And we couldn't figure out what happened. Actually it took them several days to figure out what happened to me.

And, you know, I -- it's -- I remember my art dealer came in and he said, "Come on, get out of bed." He was convinced that I had some sort of hysterical paralysis. And, you know, it was -- it took a while for everyone to figure out what in fact did happen.

GROSS: How did you come up with a system that worked for getting your brush -- your paintbrush attached to your arm in such a way that you could get the kind of mobility and control that you needed?

CLOSE: Well, you know, it's funny, I was in a rehabilitation hospital for -- after a couple of months of being in intensive care and stuff, I was moved to a rehabilitation hospital that was connected to the hospital I was in. And I began rehab, and I remember rolling down the hall one day and seeing the name on a door, it said, Occupational Therapy. I said, Oh, great, they'll help me get back to my occupation.

But in fact, it was much more about stacking spools and making things out of pipe cleaners. And I must say that the therapists were wonderful people and very helpful, but it took the active intervention of my wife, who really went to bat for me and made sure they understood just how important it was for me and my sanity to be able to get back to work.

And she convinced the therapist to stop trying to convince me how to do things that I didn't need to do, and to get back to what really mattered. And they found me a space in the basement of the building, and I equipped it as a studio and managed to start painting while I was still in rehabilitation.

GROSS: Were there times when you found yourself trying to make things out of pipe cleaners and -- I mean, because that's what you were supposed to be doing in occupational therapy?

CLOSE: Well, you know, they tried to get me to do my laundry. I said, Well, you know, I didn't do my laundry before. Why should I want to do my laundry now?

GROSS: (laughs)

CLOSE: And they tried to show me how to, you know, use a computer, and I said, I have absolutely no interest in using a computer. And I really don't want to do it with a pencil stuck in my teeth.

So it was a -- it was a fight. Because they're trying to bring everybody along, and they have a kind of general attitude towards what's liable to be helpful in a person's life. And I was looking for very specific kinds of help.

(END AUDIOTAPE)

GROSS: Painter Chuck Close, recorded last year.

This is FRESH AIR.

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia, PA

Guest: Chuck Close

High: Artist CHUCK CLOSE. He's been called "the most methodical artist that has ever lived in America" and the "reigning portraitist of the Information Age." He creates jumbo size faces on canvas (8 or 9 feet high), copying them from photographs. They are painted in a dotted faux pointillist style. In 1989 CLOSE suffered a stroke which left him paralyzed from the neck down, gaining partial use of his hand with a brace, he learned to paint all over again. Last year The Museum of Modern Art in New York presented a retrospective of his work. The companion book is: "Chuck Close" (published by the Museum of Modern Art, New York). (REBROADCAST from 4/14/98)

Spec: Art; Entertainment; Culture

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1999 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1999 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Archive Interview with Artist Chuck Close

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.