Other segments from the episode on August 28, 2019

Transcript

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. The Emmy Awards ceremony is Sunday, September 22. This week, we're featuring interviews with some of the nominees. The four-part Netflix series "When They See Us" has 16 nominations. We're going to hear from Ava DuVernay, who's nominated for directing the series and for co-writing the final episode. She's also one of the series producers.

"When They See Us" dramatizes the story of the Central Park Five. That was the name given to the five black and brown boys age 14 to 16 who, in 1989, were accused of brutally raping and nearly killing a woman who was jogging in Central Park. They became symbols of crime in New York City. Donald Trump took out full-page ads in the city's four newspapers calling for the death penalty. The five were convicted based on confessions they made shortly after they were arrested, confessions they soon after said were coerced.

In 2002, the real rapist confessed, and his DNA matched the evidence found on the victim's body. He was a serial rapist who always acted alone, and he testified that the five had nothing to do with the rape. In 2002, after the five collectively served over three decades in prison, their convictions were vacated. A year later, they filed a civil lawsuit against New York City. In 2014, they collectively received a $41 million settlement, but they couldn't get back the years of their lives they'd lost in prison.

Ava DuVernay also directed the film "Selma," which dramatized a chapter of the civil rights movement, and "13th," a documentary about mass incarceration and its echoes of the eras of slavery and Jim Crow. Ava DuVernay, welcome back to FRESH AIR. Did you know much about their story before you made this series?

AVA DUVERNAY: Only what I knew as a teenager growing up in Compton. I was on the West Coast at the same time that these boys were on the East Coast in Harlem. I was all over the place. It was big news in Los Angeles. And it really was something that I focused on because these were black boys who looked like me and my friends. They were around the same age. I'm the same age as Korey Wise.

And so to hear of this, you know, dastardly, despicable kind of devastating crime that had taken place - and particularly, the word wilding caught my attention because I didn't know what it was, and I wanted to know what that meant. So I called a cousin in New York, and I asked what it was. And he said, we don't know. We think they mean wiling out.

And wiling out is - does not mean gang-raping women. Wiling out is hanging out, you know, kind of like being free for the night, acting carefree. And it's not a wolf pack of animal-like thugs going into the park to, you know, torture and demean and assault and rape people. That's not what wiling out means. So part of what we do in our piece is try to kind of trace and track how wiling out becomes wilding becomes wolfpack becomes, you know, animals becomes, you know, a prison sentence for these five boys.

GROSS: All five were interviewed for the Ken Burns documentary, but one of them was voice only. He didn't want his face on camera. He wanted to keep his privacy. And I'm wondering how the five young - how the five men - I mean, they're in their mid-40s now - how they felt about having the story told again and having the dramatic version out there again with actors playing them because on the one hand, it's a story in which their charges were vacated. So they are not guilty. At the same time, they probably want to put the story behind them to some degree, if that's possible. So how did they feel about having you tell the story?

DUVERNAY: Well, they are all individuals, so they all felt differently about it. You know, you speak of Antron McCray, who did not go on camera for the Burns doc. I remember flying out to Atlanta to see him. You know, he was the most - he was the one with the most hesitation about doing it, but he'll always say if my brothers are going to do it, I'll do it. And I remember talking with him and just really wanting to get a sense of who he was and how he felt about the process.

And he said to me at one point, I'm probably going to have to move when it comes out. And I said, why do you think you'll have to move? And he says, I just don't want people to know. And I said, what? - like, people on your street? And he said, yeah. I said, so no one on the street that lives around you - beautiful street in Atlanta where he lives. I said, no one knows who you are? He says, they know I'm Antron Brown. And I said, so they don't know you're Antron McCray. And he says, no, I'm not Antron McCray here.

When I speak with him more more recently, I think it's changed. He still is not kind of gung ho about any part of the process, but he is wanting the story to be out there. And he understands that although it's uncomfortable for him, it's helping other people. As far as the other men, Yusef was very forthcoming and excited about telling the story, as was Raymond and Kevin. I think the other gentleman who had a little bit of hesitation was Korey Wise.

And the hesitation was only because the process of making the film is, you know, not something that folks who don't make film really know about, so it was a lot of questions about process and how deep he was going to have to go in telling his story and who he would be telling it to. So it became important to him that it didn't feel like he was on the stand or speaking with police, that the process was very intimate and that he felt comfortable in sitting down with us and telling us stories.

He did not come into a formal writers' room. We created a space for him that felt like a house, so I literally rented a house and flew them in. And they just, basically, felt like they were sitting around our house, telling us stories on the couch so that the formality of the desk and the chair and the office that felt very institutional - we broke that down, and we were able to get to stories that felt much more personal.

GROSS: So from having talked to the five men, what were some of the ways that you think the boys were manipulated by the police and prosecutors to give the false stories that they gave, to give the false confessions that they made?

DUVERNAY: Some of the ways that we show in the piece are that they were without their parents. They were not given food or water. They were asked to repeat the story. Details were inserted into the story through repetition.

GROSS: You mean they were prompted to say things that they added?

DUVERNAY: Stories were repeated and repeated again and again by both parties, and details were added through repetition. And so that was one of - that's one of the ways, and also to please who was asking them the questions, all under the kind of false belief that they would be allowed to leave if they cooperated. And that, quote, unquote "cooperation" was, you know, picking up these additional details.

I mean, one of the first questions that one of the boys was asked was, what was she wearing? And he didn't know. Kevin Richardson started to describe - I don't know - whatever he thought a white woman would be wearing, running through the park. At one point, they didn't even know she was white. They get into these details of talking about trying to sit there and piece together a story and make the person in front of them happy with it. And there were a number of different techniques that were used on them that were ultimately successful.

GROSS: Let me reintroduce you. If you're just joining us, my guest is Ava DuVernay, and her new Netflix series dramatizes the story of the five men who were known as the Central Park Five. The convictions were vacated. They received a total of $41 million in a settlement from the city of New York. And she tells their story in this new Netflix series, and it's called "When They See Us." We'll be right back after we take a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. And if you're just joining us, my guest is Ava DuVernay. She produced, directed and co-wrote the new Netflix series "When They See Us," which dramatizes the story of the five young men - who are now middle-aged men - who became known as the Central Park Five after they were accused and then, based on false and coerced confessions, convicted of raping and assaulting a woman who was jogging in Central Park.

When - about 12 years later, when the convictions were vacated, they sued the city of New York and, years later, won a total of $41 million in a settlement. And, you know, after making these coerced confessions, they recanted the confessions. And they never backed down from recanting, even after they were in prison and some of them were offered, you know, parole if they just, you know, took responsibility for the crimes that they committed. They said, we didn't commit those crimes.

DUVERNAY: That's right. Even Korey Wise, who - 13-some years in prison in the worst prisons in New York state - never wavered from the truth, which was that he didn't do it, and lying had gotten him to that place. He believes that lying got him into prison - you know, following the coercion, trying to please, being told that he would be allowed to leave if he said certain things. Those were the regrets that he lives with as a man - you know, decisions that he made, you know, trusting authority figures as a boy. He never intended to lie again. So, yeah, you know, they never wavered. They never lied again. After they all connected, they never went back on their word.

GROSS: A lot of the final episode is devoted to the story of Korey. And his story is just, like, particularly heartbreaking. He was charged only because he agreed to accompany his friend who was being picked up on - by the police on the night of the attack in Central Park. And Korey's name wasn't even on the list of people who they were rounding up. He was just - the cop said to him, why don't you come to the station house with your friend? And so to be loyal to his friend, he came along, ends up making a false confession, ends up getting convicted and ends up being the only one of the five who's tried as an adult and is sent to adult prisons, where he's repeatedly brutalized and assaulted.

And also, I think what makes hard - it harder for him is that either he can't read well, or he can't read at all. I wasn't quite sure, like, if he could read at all. But that makes it harder for him to figure out what's going on sometimes. And also, he was born - or early in childhood had a hearing impairment, so his speech is a little bit slurred.

And, like, I think all of those things must have added up to make his years just especially difficult. And I'm wondering, having met all of these men when they were in their 40s, if you feel that he is still, like, suffering a lot because of all of these extra things that he was exposed to.

DUVERNAY: Oh, yeah. I mean, he's definitely suffering. He did 13 years. His childhood - his youth was stolen from him. He...

GROSS: Right, he did more years than the others.

DUVERNAY: So yeah, I mean he's definitely affected by all of that and, you know, is trying to make his way through a new life. You know, he always says life after death, life after death. And this is what he is trying to navigate - how to be here on the outside, in the world, having gone through, you know, a type of darkness that, you know, is really almost impossible to describe. What you see in the film is not all of what he endured.

GROSS: You mean it was even worse than you depict?

DUVERNAY: There was more. There was more.

GROSS: More beatings?

DUVERNAY: There was more damage done to him, more darkness, more trauma. And so whenever he's in front of me, I just think he's a miracle. Even when he's not in front of me, I think about him so much. We've become close. And he's very - he's got a brilliance about him when you sit and talk to him. You know, most people aren't patient enough to sit there and talk to him. But when you do, you get rewards.

And so, you know, I tried to take all of my conversations with Korey, which were so heart-expanding for me - you know, he really teaches me a lot in my own life and has helped me a lot in my own life - and to take all of that and somehow put them into the final piece of this four-part film, this series, to just explain and to share the heart of this man. I mean, he is a real hero in terms of being able to look at someone and say he has battled something greater than most of us ever will and has come out on the other side to tell the story.

GROSS: So Ken Burns' documentary was made before the city awarded $41 million to the five in the settlement of the five's lawsuit against the city. And also, when the Burns documentary was made, President Trump was not - he was just Donald Trump. He wasn't president yet.

So first, I want to ask you about Trump - what it's like to see the role that he played in being a megaphone for finding the Central Park Five guilty before they were even tried. You know, just, like, days after they were arrested and charged, he took out full-page ads in all of New York's four major newspapers saying bring back the death penalty; bring back our police. And this was an argument for the death penalty, basically for children. I mean, they were 14, 15 and 16 years old.

So I'm just interested in what it was like for you to see his role in the Central Park Five.

DUVERNAY: Yes, well, he played a very famous role in the case, you know, with taking out the ads. But ultimately, you know, he's not the story. And so I made the decision just to keep it very - you know, use him very sparingly and use him, you know, with his own words and his own footage. And we do it a couple of times, and there's a couple mentions.

You know, when you really research this time, he was one of many prominent voices that were out saying all kinds of crazy stuff. I mean, Pat Buchanan basically said that Korey Wise should be lynched. He should be hung in a public park. This is the climate of the time, and it was all seen as acceptable. And it was just all happening without much of a second thought - certainly not the thought about the humanity of these boys and their families.

So yeah, as we went through, just made decisions not to lean too much into Trump. That's one of the reasons why I wanted to change the name from Central Park Five to "When They See Us." I felt that the Central Park Five had become so kind of synonymous with him and him hashtagging it and talking about it, particularly around the documentary, as he slammed Ken Burns and tweeted against him, that I just really wanted to change the perspective in which we were thinking about this case.

GROSS: Can you tell us something about their lives now?

DUVERNAY: They are great people (laughter). I love them a lot. You know, they're really - I mean, I could cry just thinking about them all. They're good, good guys.

You know, three of them live in Atlanta. It's funny because, you know, Antron McCray is the first to leave. He goes to Atlanta. He finds this beautiful black oasis in Atlanta where you - it was, you know, predominantly black town with, you know, lots of people from a lot of different parts of the country. And, you know, there's a certain prosperity that happens in some parts of the city and lots of activity and things to do.

And so he goes out there by way of Baltimore and a couple other cities that he'd stopped in and lived along the way, and he finds Atlanta. And Raymond comes to visit. Raymond is the person he's closest to. They're really best friends. And Raymond comes to visit. And Raymond's like, yo, what is this? You've got grass in front of your house?

GROSS: (Laughter).

DUVERNAY: Wait, in the back, too? Oh, no. Wait, what? And so, shortly thereafter, Raymond picks up, and he moves to Atlanta. And then a few months after that, Yusef picks up and moves to Atlanta. So three of them live in Atlanta.

And then Kevin lives in New Jersey - just got married. When I first met him, he was not married. He was dating this really wonderful woman. And I remember him thinking maybe she's the one. And I'm like, is she the one? What's going to happen? And now he's married, and they live in New Jersey with their new daughter and his stepdaughter. And they are the cutest little family.

And then Korey is in Harlem. And he has tried to live other places and just loves Harlem. You know, when he moves out of the city, he longs for Harlem. I mean, he will drive back into Harlem just to be there. He goes to Al Sharpton's weekly meetings every Saturday in Harlem - community meetings. He's a real part of the community. I've walked the streets with Oprah before. It's similar.

GROSS: (Laughter).

DUVERNAY: It's - people love him. They respect him. They look out for him. They give him a lot of love there. And that's why he likes it. It's home.

So that's what the five of them are doing, you know, in different - in various places, you know, with their emotional reckoning. You know, but my hope has been - and I've seen it a bit - that the film is - been a therapy in some ways. They're able to talk about it.

But the main thing is now people know the story. Korey is really, really adamant that people know his story. He said to me early on, it's not the Central Park Five; it's four plus one. I had a different story, and he wanted people to know. And we did everything we could to tell his story. It's a very singular story. It's different from the other guys. And so just the fact that, now, when people walk up to him, they know him, they know his story, they respect what he went through, I think, is - I hope and I pray that it has a positive effect on him and on all of them.

GROSS: Ava DuVernay, thank you so much for talking with us.

DUVERNAY: Thank you so much. I appreciate it. Thanks for having me.

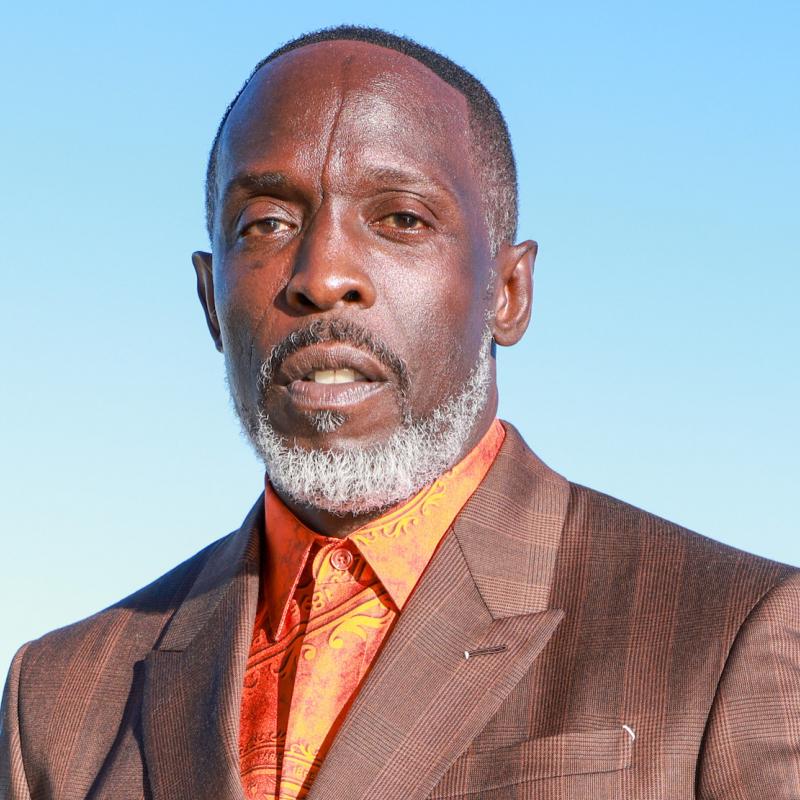

GROSS: Ava DuVernay directed, co-wrote and produced the Netflix series "When They See Us," which is nominated for 16 Emmys, including two for DuVernay - best writing and best directing for a limited series. After we take a break, we'll hear from Michael K. Williams, who's nominated for an Emmy for his performance in "When They See Us" as Bobby McCray, the father of Antron McCray, one of the five wrongfully convicted boys. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. It's Emmy week on FRESH AIR. The next nominee we're going to hear from is Michael K. Williams. He's nominated for his performance in the Netflix limited series "When They See Us" as Bobby McCray, the father of Antron McCray, one of the five black and brown boys who became known as the Central Park Five. They were wrongfully convicted of assaulting and raping a woman who was jogging in Central Park in 1989. The series has 16 Emmy nominations.

Michael K. Williams became famous for his roles in fictional crime series. In "The Wire," he was Omar, the fearless stick-up man who stole money from drug dealers. In "Boardwalk Empire," he was Chalky White, a bootlegger who later runs a nightclub in Atlantic City.

I spoke with him about his life in 2016, when he was co-starring in the HBO series "The Night Of." He played an inmate who basically controls his prison block in Rikers Island, the notorious jail in New York City. We started with a clip from a scene in which he's giving advice to a newly arrived prisoner, a young man who is clueless about prison life. The young man is played by Riz Ahmed. Michael K. Williams speaks first.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "THE NIGHT OF")

MICHAEL K WILLIAMS: (As Freddy) You see, us and the guards, we all from the same hood. Some of us even grew up together. They know our families; we know theirs. Look; family's everything, right? It is in a Muslim family.

RIZ AHMED: (As Naz) Yeah.

WILLIAMS: (As Freddy) I'll tell you something, man. See those brothers you pray with, the nation of Islam? They're not your friends. In fact, they hate your ass because you're a natural-born Muslim and they're just phony jailhouse opportunists looking for better food, don't know the difference between Cairo, Egypt, and Cairo, Ill.

AHMED: (As Naz) I'm Pakistani, not Egyptian.

WILLIAMS: (As Freddy) Yeah, well, my ancestors came from Doheny and not the Congo. Who gives a [expletive], man? See, you're a celebrity in here, and I'm not talking the good kind. Dude kills four guys over some dope - OK. But murder a girl? Rape a girl?

AHMED: (As Naz) I didn't.

WILLIAMS: (As Freddy) It doesn't matter. Makes no difference. See, there's a whole separate judicial system in here. And you've just been judged and juried, and it didn't come out good for you.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

GROSS: Michael K. Williams, welcome back to FRESH AIR.

WILLIAMS: Thank you. Thank you, Terry.

GROSS: I really like your performance in this series. What did you want to know about your character when you took the role?

WILLIAMS: You know, when I first got the part, it wasn't really - nothing I wanted to know about him. I'm so familiar with people like Freddy, you know, from my childhood and, you know, from my personal life. You know, I have family members that remind me of Freddy - you know, just all this potential that just got misguided and led to bad decisions. And those bad decisions came with consequences.

I know that all too well. And so it wasn't something where I needed to do research to understand that world. I still visit my family that's incarcerated. And I see the good days. I see the bad days. I see the growth. I see what they lost by being incarcerated. And I saw the gains. I just dove into that.

GROSS: You have family who's in jail now?

WILLIAMS: Yes, I have a nephew, Dominic, Dominic Dupont, who I'm extremely proud of. If there were such a term as a model prisoner, he'd be the poster boy. You know, he went in at a very early age. He defended his twin brother in a fight, and they got jumped, and a gun went off, and someone lost their life at the hands of my nephew. And I believe that had we had the proper money to hire the high-powered lawyers, his outcome probably would've been different. But, you know, did he do the crime? Yes. Did he do the time? Absolutely.

But his record, what he's shown society, how he's grown in there - we're talking got his education, got married in there - managed to find a good woman and got married in there. He mentors young men that come in behind him, whether it's a HIV/AIDS program or a Scared Straight program. While doing all of this, he still managed to keep his respect and his dignity. And, as we all know, that's not easy to do in prison. You got to fight for your respect or you get run over. And he was able to ride that thin line.

GROSS: So your character is in jail in Rikers Island...

WILLIAMS: That's right.

GROSS: ...Which is a very notorious jail in New York City. Did you know people in Rikers Island when you were growing up? Did you hear a lot of Rikers Island stories when you were growing up?

WILLIAMS: Yeah, D-block (ph). Yeah, House of Pain, or 4 Main House of Pain. You know, and I just want to take a moment to just say - to give a shoutout to all my brothers and sisters who may be incarcerated on the island from New York City. Just keep your head up, man, and just keep striving to be the best you you could be. You know, they could lock your body up, but they can't lock your mind up. Just keep striving. Tomorrow's a better day.

GROSS: We're listening to the interview I recorded with Michael K. Williams in 2016. Eighteen months later, in January 2018, his nephew Dominic Dupont was released from prison after receiving a commutation citing his remorse and his nine years of work as a mentor to at-risk youth. He'd served 20 years of a 25-years-to-life sentence. He's currently working as a counselor to at-risk youth.

In this next part of my interview with Michael K. Williams, we talked about a minister who helped him through a very tough time. We got into that by talking about an interview he'd done for a series he was hosting for Viceland TV called "Black Market."

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

GROSS: You interview a minister, Reverend Ronald Christian, who ran the Christian Love Baptist Church, a church that bordered Newark in Irvington, N.J.

WILLIAMS: Correct.

GROSS: And this was a church that was really important to you during a difficult period of your life. The episode is dedicated to the memory of this reverend. So in between the time that you recorded the interview and last November when he actually died - I don't know how much time elapsed, but you must have been really shocked. He was found dead on the floor of the church. Does anyone know what happened?

WILLIAMS: His heart just gave out, man. He got tired. You know, this was a man that, you know, I've never seen someone give so much of themself - 100%, night and day. He just never stopped. He was always there in the community. If you're familiar with Essex County, and particularly Irvington and, you know, certain parts of the Oranges and especially Newark, you know that there's a lot of violence that goes on there, a lot of death. Life is very cheap on those streets. And he was always there. You know, when...

GROSS: What did he do for you? You came to him during a difficult part of your life.

WILLIAMS: When I came around, I was broken. I came through those doors, I was broken.

GROSS: When was this?

WILLIAMS: Around the second - more like third season of "The Wire." I was on drugs, and I was in jeopardy of destroying everything that I had worked so hard for. And I came in those doors, and I met a man who had never even heard of "The Wire," much less watched it. He was somewhere else in the Bronx preaching at another church when I first went there. And he stopped everything he was doing, ran back to New Jersey, just because his team at the church told him that some, you know, some guy named Omar was in trouble and needed to speak to him.

And he came in his office, and he says, write your full name down and your email. He said, I'm going to go get you a Bible, man. You could keep that. And we going to spend the rest of this day. And I was like, bet. So I wrote my full name down, Michael Kenneth Williams. And as he's leaving the office, he turns around. He says, so what you want to be called, man? I said, well, you know, my name is Michael, but, you know, I could do Mike, you know? He said, well, why everybody saying Omar - Omar in trouble? And I was like, oh, this dude - clueless. And it had nothing to do with Hollywood light or who I was in my job - just basic human being stuff.

And one of his biggest sayings was, Imma (ph) love you till you learn to love yourself. And he never judged. You know, he just nudged. You know, I could - you know, if you want to stop this pain, I can help you with this, but until you're ready, I'm your brother. He never - you know, I'm not saying he accepted me in my dysfunctionalism, but he loved me in it. And it worked. It worked for me. It got me to want to become a grown man, to grow up and to stop acting foolish, or at least to make the attempt to stop acting foolish, you know?

GROSS: We're listening to my interview with Michael K. Williams, who is now nominated for an Emmy for his performance in the Netflix series "When They See Us" about the Central Park Five. We'll hear more of the interview after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF ANDREYA TRIANA SONG, "SONG FOR A FRIEND")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to my 2016 interview with Michael K. Williams. He's now nominated for an Emmy for his performance in the Netflix series "When They See Us." Earlier in our interview, he talked about how he'd used drugs earlier in his life.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

GROSS: So why do you think you started using drugs when - or started using them again - I'm not sure which - after "The Wire" was on...

WILLIAMS: A little bit of both (laughter).

GROSS: ...After you'd become successful because you'd think on the surface that that would be a period when your self-esteem would be, like, really good because you were so great in the role and people, like, loved you in it.

WILLIAMS: Yeah. See, that's the trick. That's the trick. Feeling good, that's got to come - it's got to come from the inside out, not the outside in. And, you know, you, you know...

GROSS: Oh, you didn't feel worthy.

WILLIAMS: No. Hell no, I didn't feel worthy of opportunity like that. Then, you know, when I was given this character as Omar, I could've used it as a nurturing tool for myself. It could've been cathartic for me. I decided to wear it as a Spider-Man suit, you know, and just fly around and go, whee, look at me. I got web in my hands. You know, and instead of actually doing the work and finding out how I could use this character to make myself feel better about me, I just - I used it instead of me. It was - I - you know, like, it was like my crutch.

And so when "The Wire" and the character of Omar ended, I had zero tools, personally speaking, in how to deal with letting that go. I wasn't going around robbing people or anything stupid like that, but I definitely wore that dark energy that Omar was. He was a dark soul, tortured soul. And I just woke all of that up and lived in that so when - and that's what people was attracted to - his - whatever they were attracted to, I just didn't know how to differentiate, OK, that is Omar's love, and then you have Michael's love. The lines got blurred. It was a little too close to the white meat at the time. It's an old figure of speech in the streets...

GROSS: OK (laughter).

WILLIAMS: ...When you cut somebody to the white meat. It was a little too close to home, that character, and I didn't equip myself with the tools of how to wash that off my psyche.

GROSS: You know, we were talking about how you didn't feel powerful when you were young, and playing Omar felt like a real stretch for you. And you had this kind of dissonance between how you felt as a person and how you portrayed Omar. Something I know for sure that must've taken a lot of courage was when you were, I guess, in your 20s when you decided to leave a job that you'd finally gotten with a pharmaceutical company to try to make it as a dancer, you know, to try to have some kind of career as a performer. And I think, you know, that always takes a lot of courage to leave a secure job, even if it's not a job you especially like, and just kind of, you know, jump into the water not knowing if you'll float or not.

WILLIAMS: You know, Terry, I was being a bit of a butt [expletive] when I did that to my - that was a way to stick it to my family, especially my mom. You know, in my family, there are three things that you're taught to do. You either get an education or you go into the military or you get a trade with your hands. You know, the men in my family, that's what you do. And I kind of, like, failed at all three.

Yeah, so I went and got a job at Pfizer pharmaceuticals. Like, I was a temp job, and I worked there for a year. They were about to make me a permanent when I saw this Janet Jackson video. And it was like my spirit got stirred by the visual images that were shown in that video, the strength. You could see, like, these just different people - you know, some tall, some short, male, female, light-skinned, dark-skinned. It wasn't just this everybody was pretty with perfect teeth. You saw some jagged edges in that formation in "Rhythm Nation." Yet, when they all came together, they moved like one.

Mixed with the lyrics - and I'm a huge Janet Jackson fan. It's - I couldn't run that fast. So it stirred my spirit. My spirit got awoken. My creative sources, energy got awoken the first time I saw that video. And it was a way to, like, you know, stick it to my mom, like, yeah, I'm going to do it my way. I got us some Frank Sinatra, you know?

GROSS: (Laughter).

WILLIAMS: So it was a combination of, like, you know, I don't want to get an education. I don't want to get a trade. I don't want to go to the Army. I want to do this. I'm going to dance. And, you know, lo and behold, I got lucky. I started getting work. That wasn't in the plan to actually, you know, become something.

GROSS: (Laughter).

WILLIAMS: I just wanted to have fun and make a few dollars, you know (laughter)?

GROSS: What kind of dancing had you done before?

WILLIAMS: OK, now, when I say I used to be a dancer, I need you to know that I was a complete and utter hack.

GROSS: (Laughter).

WILLIAMS: I - you know, I have way too much respect for dancers and real choreographers to really call myself one. I just had a real good way with rhythm. I love movement. I love music. And I am a good mimic. I could make it look like a pirouette, but if you really look at my form, any real dancer could tell you, that's some garbage right there.

So, you know, I was just that club kid in the clubs in New York City with his, you know, with his suspenders on backwards, the loud floral shirt, the baggy jeans, the high-heel marshmallow shoes with the big platform doing half-splits in the club. I was that dude. And I got really blessed and was able to parlay it into a dance career being at the right place at the right time and surrounding myself by the right people.

GROSS: We're listening to my interview with Michael K. Williams, who's now nominated for an Emmy for his performance in the Netflix series "When They See Us" about the Central Park Five. We'll hear more of the interview after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF IN THE MIDNIGHT HOUR, ADRIAN YOUNGE and ALI SHAHEED MUHAMMAD'S "BETTER ENDEAVOR")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to my 2016 interview with Michael K. Williams. He's now nominated for an Emmy for his performance in the Netflix series "When They See Us."

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

GROSS: Let's talk about another turning point in your life. When you were 25 - I think it was, like, the night of your 25th birthday - you got into a bar fight. That's when your face was slashed with a razor. And your - the scar that runs down the middle of your forehead - that's become almost like a signature. You know, it's almost like you're known for that. It's part of your look, in a way. And you've managed to make it a strength instead of something horrible that you have to cover up that's going to hurt your career or anything like that.

But when it happened, what did you think, assuming that you survived, because I think you were also cut in your throat that night?

WILLIAMS: Yeah, the second cut of that fight ends right at my jugular, yeah.

GROSS: How did you think that scar on your forehead, which is visible, was going to affect your career as a performer?

WILLIAMS: I didn't think at all. You know, when I first got that scar, when I got jumped that night, I was just beginning my dance career. And I was - I had just gotten a gig as a model, like a - there was this company called Rock Embassy that made tour jackets for, like, various recording artists that went on tour. And they would sell them at, you know, as merchandise. And I was the big - one of the big spokesmodels for that company. And so I think the - it went in all the magazines, the hip-hop magazines. There were, like, posters all in the subway stations. And that whole wave of press went out on November 20 or the 21. And then I get this big slash down my face on the 22. So immediately, I thought my modeling career - well, that's over. OK, we're going to - now we're going to focus on the next thing on your resume - dancing, yeah. Scratch model. OK, now we're just a dancer.

So, you know, and I just want to say, man, there are some good advantages that came out of growing up in my community. That whole, like, fake tough-skin thing, it kind of worked for me in this instance because I refused to look at myself as a victim. I kept it moving. I didn't allow myself to feel weak over that incident because I knew that, mentally, I didn't have what it would have taken to really deal with what had just happened. So I didn't mentally go there. They wanted me to seek, like, therapy for trauma. I shut all of that down. I said, no, I'm good.

GROSS: What about the scar from your ear to your jugular? I don't think I've noticed that ever. Is that visible?

WILLIAMS: Because I purposely wear my beard. It kind of just hides it back there.

GROSS: Did you think you weren't going to make it through that night?

WILLIAMS: You know, I think - yeah, I think a lot of people thought that I wasn't going to make it to see 30. You know, my mom didn't think I was going to see 30, you know.

GROSS: Does she watch your TV shows?

WILLIAMS: No, she liked "Boardwalk Empire." Every time that character would come on, she (laughter), oh, Nucky (laughter), oh, Nucky. And I'm like, Ma (laughter).

GROSS: Why don't we hear a scene from "Boardwalk Empire"?

WILLIAMS: Yeah.

GROSS: And "Boardwalk Empire" was HBO's series set during the Prohibition era in Atlantic City. And Steve Buscemi played Nucky, who was, like, the king of Atlantic City...

WILLIAMS: Atlantic City.

GROSS: ...And basically controlled politics, controlled the bootleg liquor. You play the most powerful African American in the city, and you have a bootleg operation of your own. And then with Nucky's help, you run a very swank nightclub in Atlantic City. And so you've accumulated a lot of wealth.

And in this scene, you're at a dinner party at your very well-appointed home with your wife and children. Your daughter's boyfriend, a medical student, is there, too. And you're feeling very self-conscious because you're from the South, you're from the country. And he's very urban. He's educated. He's refined. There's a sumptuous duck dinner on the table. Your wife asked the medical student to say grace. You're a little drunk, and you keep interrupting him and talking about how they should all be eaten Hoppin' John - rice and black-eyed peas. Here's that scene, and it starts with the boyfriend.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "BOARDWALK EMPIRE")

TY MICHAEL ROBINSON: (As Samuel Crawford) Lord, we...

WILLIAMS: (As Chalky White) Is that a duck?

NATALIE WACHEN: (As Lenore White) Yes, Albert. Of course it is. Please, Mr. Crawford.

ROBINSON: (As Samuel Crawford) Lord, we thank you...

WILLIAMS: (As Chalky White) I thought I asked for Hoppin' John.

WACHEN: (As Lenore White) There's duck, peas, carrots, fresh-baked biscuits.

CHRISTINA JACKSON: (As Maybelle White) I made chocolate pudding for dessert.

ROBINSON: (As Samuel Crawford) We'd like to thank you for the...

WILLIAMS: (As Chalky White) I asked a question.

WACHEN: (As Lenore White) Albert, please. She made that pudding all by herself.

ROBINSON: (As Samuel Crawford) It's very nice.

WILLIAMS: (As Chalky White) Where the damn Hoppin' John?

WACHEN: (As Lenore White) Albert, you know that's not proper food for a guest. Now let's allow Samuel to finish.

ROBINSON: (As Samuel Crawford) Lord, we come together to...

WILLIAMS: (As Chalky White) Well, maybe our guest would've liked some.

ROBINSON: (As Samuel Crawford) Oh, I have always enjoyed that type of food, sir.

WILLIAMS: (As Chalky White) What type of food?

ROBINSON: (As Samuel Crawford) My grandma would make it.

WILLIAMS: (As Chalky White) I say something funny, son?

ROBINSON: (As Samuel Crawford) I beg your pardon?

WILLIAMS: (As Chalky White) You laughing. What's the joke?

WACHEN: (As Lenore White) Hoppin' Johns, Albert. You're being ridiculous.

WILLIAMS: (As Chalky White) I've been eating rice and beans all my life. Tell me it ain't good enough.

WACHEN: (As Lenore White) You'll have to forgive my husband's country ways.

ROBINSON: (As Samuel Crawford) Oh, I completely understand.

WILLIAMS: (As Chalky White, slams table) This is my house, and my country ways put the food on this damn table.

WACHEN: (As Lenore White) Albert, you're drunk.

ROBINSON: (As Samuel Crawford) Sir, I apologize. I'll leave.

WILLIAMS: (As Chalky White) You stay right where you are, son, right there inside the house. Pretty clear who the field [expletive] is.

GROSS: That was Michael K. Williams as Albert - Chalky - White on "Boardwalk Empire."

So your character in "Boardwalk Empire" is from the South, from the country. You're very urban. You're from Brooklyn. What did you feel like you had to learn about the South and about Prohibition era to play Chalky White?

WILLIAMS: Well, you know, Terry, there wasn't nothing I had to learn about the South. I'm first-generation Bahamian from my mother, but my father is straight from a small town in South Carolina called Greeleyville. So I have full working knowledge of the South. What "Boardwalk" and portraying Chalky White did for me was it gave me time with my dad, who's no longer here, again, but not in this time frame. It allowed me to go back to hang out with him in his childhood, what he went through in coming up as a man, him and my Uncle Jayhu (ph), my Uncle Par, my godfather Junior, my Uncle Tommy. All these men are deceased, and Chalky White gave me time to hang out with them in their era when they were young men coming up. That's what they all went through. That's what they lived in.

GROSS: So both in "The Wire" and "Boardwalk Empire" your characters are shot to death. In "The Wire," you're shot by a kid. In "Boardwalk Empire," it's almost like a firing squad, this, like - there's, like - I don't know - five gangsters who just kind of line up and shoot you, and you die off-camera. It kind of fades to black. Can I ask you what it's like to experience your character's death?

WILLIAMS: Oh, wow. That's a first. That is the first time I've ever been asked that question. And you mentioned who they got shot by, young - a black teen on the streets of Baltimore. Chalky White got shot by a firing squad, you know, ironically, of all black men in Harlem. And it speaks to what's happening today, you know, in our society. And so those images that you see on "The Wire" and Chalky - and in "Boardwalk Empire," and particularly with my character's demise, I don't take that lightly, you know?

And anybody that was on the set that day when Idris Elba and I had to shoot the scene where Stringer Bell dies, I was shaking like a leaf and crying, you know, because I did not want to do that. It just didn't feel right. Like, how do you come to these two dark-skinned, strong-minded black men, strong-willed black men - as we say in the hood, these two kings - how is it always they've got to come on and, you know, there's a faceoff and one of them got to die? You know, I didn't want to be a part of that. I didn't know - at that point, I questioned, what am I doing? Am I telling the truth or am I perpetuating the problem? I suffered with that on "The Wire," you know, and that weighed on me. And even though it's fake, where I go in my psyche, it - trust me, it is very real. And it comes equipped with all those emotions that comes from having killed someone that looks like you. You know, how do you deal with that? Where do you go with that? That's where I take it.

GROSS: Michael K. Williams, recorded in 2016. He's nominated for an Emmy for his performance in the Netflix limited series "When They See Us," based on the story of the Central Park Five. He plays Bobby McCray, the father of Michael McCray (ph), one of the five boys who was wrongfully convicted. The series has 16 nominations.

Our Emmy week continues tomorrow with two more nominees - Christina Applegate, who's nominated for her performance in the comedy series "Dead To Me," and Natasha Lyonne, who's nominated both for her acting and her writing on the comedy series "Russian Doll." I hope you'll join us.

FRESH AIR's executive producer is Danny Miller. Our technical director and engineer is Audrey Bentham. Our associate producer for digital media is Molly Seavy-Nesper. Roberta Shorrock directs the show. I'm Terry Gross.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.