Remembering Scotty Moore, Elvis Presley's First Guitarist And Manager

Moore, who died Tuesday at the age of 84, booked gigs for Presley during the early part of the musician's career. He later penned the memoir, That's Alright, Elvis. He inspired a generation of guitarists. Originally broadcast in 1997.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on July 27, 1997

Transcript

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. My guest, Matt Ross, is hilarious in the HBO comedy series "Silicon Valley" as Gavin Belson, the narcissistic and ruthless CEO of Hooli, a Google-like tech giant. He was scary in the HBO series "Big Love," in which he played Alby Grant, the son of the leader of a polygamist cult group.

Ross has written and directed a new film called "Captain Fantastic" about a father who is so disillusioned with American capitalism and culture that he's living off the grid with his six children in the woods of the Pacific Northwest. He looks and dresses like an 1960s hippie. The family car is a repainted old school bus named Steve. The father homeschools his children and teaches them how to hunt and scavenge for food. He gives them daily instruction in meditation and survival skills, including extreme physical fitness training. He's also created a Great Books curriculum for them.

His wife is hospitalized when the movie begins. When she dies, he and his children get on the bus and drive to the funeral, forcing them to function in the world they've dropped out of. Everyone's values end up being challenged.

Let's start with a scene from early in "Captain Fantastic." The father, played by Viggo Mortensen, is about to get on their bus, Steve, and drive into town so he can use a phone to check on his wife's condition. One of his daughters speaks first.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "CAPTAIN FANTASTIC")

SHREE CROOKS: (As Zaja) Why does mommy have to be gone so long?

VIGGO MORTENSEN: (As Ben) She hasn't been gone very long.

SAMANTHA ISLER: (As Kielyr) Actually, it's been three months, two weeks, six days and 11 hours.

GEORGE MACKAY: (As Bodevan) Mom is very ill.

ISLER: (As Kielyr) Don't talk to us like we're your inferiors.

MORTENSEN: (As Ben) Well, he's right. Mom needs to be in the hospital right now.

ISLER: (As Kielyr) But you said hospitals are only a great place to go if you're a healthy person and you want to die.

SHREE: (As Zaja) You said Americans are undereducated and over-medicated.

ISLER: (As Kielyr) And you said the AMA are avaricious whores only too willing to spread their fat legs for Big Pharma.

MORTENSEN: (As Ben) All those things are true. But mom does not have enough of the neurotransmitter serotonin to conduct electrical signals in her brain.

NICHOLAS HAMILTON: (As Rellian) Exactly when is mom coming back?

MORTENSEN: (As Ben) That's what I'm going to go find out. Be good, monkey butts.

SHREE: (As Zaja) See you later, dad.

CHARLIE SHOTWELL: (As Nai) Bye.

MORTENSEN: (As Ben) Bye, guys.

GROSS: Matt Ross, welcome to FRESH AIR. I think we get a sense of how the father communicates with his children when he describes mom doesn't have enough gabapentin for the neurotransmitters in her brain or whatever. How do you think the father, played by Viggo Mortensen, sees himself in your film?

MATT ROSS: I think he sees himself as trying not to be their friend, but their teacher. And I think like all of us, he's doing the best he can and is trying to set a good example. He's challenging his children in a way that most of us don't. And for some people, that's shocking. For me, it's not. I think - you know, in the script he says, I tell the truth to my children. I don't lie to my children. And I think that's probably the baseline for him.

GROSS: He wants to be a free thinker and he wants his children to be free thinkers. At the same time, he's kind of an authoritarian father. He maintains total control over their time, what they're exposed to, who they see - and they really don't see anyone - what they're allowed to eat. There's no other teachers or friends or friends' parents or television or movies...

ROSS: ...Except for the mother.

GROSS: Except for the mother, and she's in the hospital. So there's no outside source other than what's filtered through him. And it's such a paradox that I don't think he realizes that he's rebelling against authority and he's created this authoritarian system that he controls.

ROSS: Yeah. Well, I think you're right. I think - well, a great deal of that is intentional. I mean, I think that he is like hopefully all the characters in the film complex and flawed. He's not the protagonist, and he's not the antagonist. At times he is both, as are other characters.

GROSS: So you have two children. Were you starting to question your own values as a father while you were making this movie, trying to...

ROSS: Yeah, precisely.

GROSS: ...Examine your own motivations and everything?

ROSS: Absolutely. Yeah, I think, you know, the genesis of it was precisely that. I have two kids. At some point, I was thinking a great deal about what my values are, what I wanted to pass to my children. I mean, all of us - anyone who has a child - that, you know, on some very primal, basic level you want to protect them and prepare them to live lives as good global citizens. You know, as tolerant human beings and compassionate human beings. And you want to help prepare them for when they leave the nest. That's on a basic level.

And then I - you know, I was - I think really when I retroactively look at what was going on in my own life, I think my wife and I were probably discussing and/or arguing quite frequently about what our values were. And, you know, you're curating this human being's life.

You are deciding everything - what they eat, what they read, what they watch, whether it's safe for them to walk down the street, you know, to go to the book store by themselves or the library or whatever at whatever age. And for every family it's different. And I was - I had a lot of questions about what I wanted to pass on to my children. And I put them into the form of a narrative really asking those questions.

GROSS: So I know that you spent some of your childhood living on communes with your mother, and I assume you drew something from that for this movie because some of his values, some of his lifestyle is similar to what people wanted to do when they were creating, like, alternative communes...

ROSS: Sure.

GROSS: ...In the '60s. I'm always interested in the children who grew up on the communes and how they were shaped by it. So since I assume you're drawing on that in part for your movie, can I ask you a few questions about that?

ROSS: Yeah, of course. One thing...

GROSS: Yeah?

ROSS: ...Just so you know - yes, my mother started or was part of starting various alternative living communities. I'm always very - it's very important to me to make clear that they weren't hippie communes. I think that's an inaccurate term. It's a reductive term, but mainly it's an inaccurate term only because it was the 1980s and not the '60s. And these people were clearly not hippies. They were - they tended to be artisans or artists or simply people who did not want to live in a urban environment.

And some of them had families. Some of them were just by themselves or with a partner. Some of the homes had electricity and plumbing, some did not. My memories are different than certainly what people think of as some kind of stereotypical hippie commune. You know, they were things like my brother and I walking for hours and hours with our bow and arrows through the forest. I mean, like eight hours with our bows and arrows. And, you know, my memories are more just being out in nature.

And I was not homeschooled. I went to public school. At one point, we lived something like eight miles from a cement road and 35 or 40 minutes away from the general store, which was literally called the general store, and about an hour or - and change from a town of a thousand people. So we were very, very far in the forest.

And I remember feeling very - probably that there were no other kids of my own age that I - you know, that I really had - that I was able to spend a lot time with other than my brother, and feeling like well, you know, when you're that age you just want to go over to someone's house and - forget just watch TV or hang out. It was just - I wanted to just be in the presence of kids my own age. And that was true. And we also lived in a teepee. You know, at one point in the summer, we'd live in a teepee and go swimming in the pond.

GROSS: What always fascinates me about this kind of scenario is for the parents, it's an alternative. It's a kind of - an idealized attempt at creating a life different from, outside of the mainstream. For a child growing up into it without the choice of whether they want to be there or not, it's not really an alternative because you don't know what it's an alternative to. Like, you haven't been exposed to mainstream culture, so you haven't chosen the alternative.

And I'm not asking, I guess, whether it's fair or unfair to raise a child that way. But at what point did you realize that you were in this - what was supposed to be a more idealized, you know, more kind of utopian or whatever community, but that there was a world outside of that that you were not only cut off from, but you didn't know that much about?

ROSS: Well, the truth is I wasn't born into that. I had lived in urban environments. At that - by that time, I had lived in England. I had been to Africa. My parents were separated and divorced when I was really...

GROSS: ...OK, you're really worldly (laughter).

ROSS: Yeah, (laughter) my parents were separated and divorced when I was quite young. And my mother wanted to start - I don't know if you're familiar with Waldorf schools. There was an Austrian philosopher and theologian, an educator named Rudolf Steiner. And you find these Waldorf schools - they tend to be in sort of progressive and upper-middle-class communities in the United States. But they find them all over the world.

And she was interested in starting a Waldorf school in the United States, so we lived in England while she became accredited to do so. And by the time we'd been on some of these communes - or, you know, alternative living situations, I'm not sure what the proper term would be - I had lived around the world. But to get to your point a little more, I think that she was a seeker of sorts.

You know, look, the film is not about alternative living communities. That's sort of the backdrop for the beginning of the movie. I think if the movie is about anything, it's really about the choices we make as people, specifically as parents. But I remember - you know, my mother's choices were - she clearly wanted us to be connected to certain things that we would not be connected to if we lived in an urban environment.

I remember she - we slaughtered goats that we would then eat, and she wanted us to see that. And we were pretty young. And those images are still in my head. I think if you ask her, she probably regrets (laughter) - I think she'd say that we were too young to see that. But I think - you know, as I'm thinking about this, I think that her goal was to probably show us our food source. You know, say look, you know, we eat certain things, but it's important to know where this comes from.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Matt Ross. He wrote and directed the new film, "Captain Fantastic." And he co-stars in "Silicon Valley" and co-starred in "Big Love." Let's take a short break here, then we'll talk some more. This is FRESH AIR.

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR, and if you're just joining us, my guest is Matt Ross. He wrote and directed the new film "Captain Fantastic" and he co-stars in the HBO comedy series "Silicon Valley" and co-starred in the HBO series "Big Love." Let's talk a little bit about your role in "Silicon Valley."

ROSS: Sure.

GROSS: "Silicon Valley" is an HBO comedy series about a struggling tech startup called Pied Piper. And you play Gavin Belson, the CEO of a tech giant, a Google-like company, called Hooli. And before we really talk, I want to play a scene. So you - your character uses a lot of, like, feel good, techie, optimistic jargon but you're ruthless and totally lacking in empathy. You've created a unit called nucleus, which is designed to compete with Pied Piper's data compression platform, a platform that would make it really fast and really easy to store massive amounts of data. But your unit, nucleus, has been failing and you're angry that Richard Hendricks, the young founder of Pied Piper, is doing a better job than nucleus.

So in this scene, your marketing people have just shown you a new ad, and it starts with a woman doctor examining a young girl. And then we see a happy girl and we see two people shaking hands - all very inspirational. And along with these images we see the words inspire, believe, imagine, innovate. So here's the scene that happens after we see the commercial.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "SILICON VALLEY")

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #1: (As character) And that is the very first spot in our new campaign, heralding the upcoming release of nucleus this January at CES. Any questions?

ROSS: (As Gavin Belson) I have a question. That was horrible. I just got humiliated by a [expletive] teenager, a tech-crunch disrupt and you give me this tampon ad, a girl with diabetes on a swing.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #1: (As character) I think she has cancer, at least that's how I read it.

ROSS: (As Gavin Belson) I don't care what kind of disease she had. All I care about is that nucleus is better than Pied Piper. Hendricks just left us all in the dust. If we get this wrong, we could blow the business opportunity of a lifetime. Data creation is exploding. With all the selfies and useless files people refuse to delete on the cloud, 92 percent of the world's data was created in the last two years alone. At the current rate, the world data storage capacity will be overtaken by next spring. It will be nothing short of a catastrophe. Data shortages, data rationing, data black markets. Someone's compression will save the world from datageddon (ph) and it sure as hell better be nucleus and not Pied Piper. I don't know about you people, but I don't want to live in a world where someone else makes the world a better place better than we do.

GROSS: (Laughter) That last line became a famous line from "Silicon Valley" - I don't want to live in a world where someone else makes the world a better place better than we do. What was your first reaction when you saw that line in your script?

ROSS: Well, that line was actually - it's funny you're pinpointing that because that line was actually something that Alec Berg just threw at me that I don't believe that was in the script until we were shooting. And, you know, the writers, who are all phenomenal I think they are - Mike Judge and Alex Berg and Clay Tarver and Dan O'Keefe who I believe make up the, you know, the major brain trust of the show. And there are other writers, of course, that I'm not mentioning.

But Alec was either directing that episode - I don't remember - or he was - he was there as they are frequently and - if not every day. And he just came up and he was throwing me different lines, say this, say this and I remember just trying to get my mind around it because it was - the construction of it was odd and and it's one of the reasons why it's so funny. But it was a - it was a great line and I think when he was pitching it to me I realized how fantastic it was.

GROSS: So in a moment I'm going to play a clip from "Big Love" in which you're the son of a cult leader and then become the leader of the cult. Can you compare for us playing a cultish kind of personality in the tech world to - and play that - playing that for comedy and playing a cult leader in a very kind of threatening, serious way in "Big Love?"

ROSS: Well, we don't know much about Gavin's personal life at all. I mean, I'm a secondary character in the show, and so I think I'm used as a force of antagonism largely or some comedy. And that's not dissimilar in how Alby functioned in that drama as well. I was a force of antagonism and sometimes the people on the compound were used for comedy. But Alby was shown...

GROSS: And Alby is on "Big Love," the son of a cult leader.

ROSS: Correct, yes, Alby Grant - Albert Grant - otherwise known as Alby on "Big Love." And he, you know, he struggled with - he was a - he was homosexual in a world where that was absolutely verboten obviously. It was a deeply religious community. And so he was closeted. He was - he had many wives in this polygamist community, but he couldn't - his authentic self, his true self, could never be a public face. And so he was tortured in many respects. He was also - part of the narrative was that he had a very punishing, emotionally punishing, father played by Harry Dean Stanton who never allowed him to be - to have any kind of power or to have any voice in that community and - or in his life. And so, you know, I always viewed Alby - Alby was very much - he was such a broken man. He was - he struggled and his struggles were part of the narrative. So in terms of what I was allowed to do as an actor, there was, I would say, slightly more complexity that was allowed to come out and certainly more vulnerability.

GROSS: Let's hear a scene from HBO's "Big Love." And you played Alby, the son of the leader of a polygamist cult group that broke away from the Mormons. They kind of live in squalor in their own compound called Juniper Creek. And Alby is dominated by his father, the cult leader, who's considered the prophet.

But when the father dies, your character, Alby, inherits the position but because you've been so emotionally abused by your father you're weak and insecure. But you do know how to threaten and intimidate anyone who you see as your enemy. And you've got a lot of enemies, including your brother-in-law Bill Henrickson, who grew up in the Juniper Creek cult and broke away to form his own polygamist family. He wants to take over Juniper Creek and questions your vision and your leadership ability.

And in this scene, you're talking to a young, very attractive young man who you've hired to do your dirty work. You've also hired him to strip naked so you can stare at him because you're a very repressed, deeply closeted gay man. So here you are talking to this man who you've hired. You're very angry at all the groups trying to undermine you.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "BIG LOVE")

ROSS: (As Alby Grant) I have no vision? I keep peace between the Greenes and the Walkers and the insane warring factions. I am purifying the compounds. I do have vision yet I get spat on. Well, it is time for that insolent suburban shopkeeper to go.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #2: (As character) Go where?

ROSS: (As Alby Grant) To his grave. And I want you to dig it. Go contact him and tell him that you have information that is harmful to me and that you're willing to sell it to him.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #2: (As character) What kind of information?

ROSS: (As Alby Grant) It doesn't matter.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #2: (As character) Well, what if he asks?

ROSS: (As Alby Grant) Listen to me. It doesn't matter. You'll ask him to meet you.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #2: (As character) When?

ROSS: (As Alby Grant) Tomorrow.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #2: (As character) How much are you going to pay me?

ROSS: (As Alby Grant) Why is it always about the money with you?

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #2: (As character) It's - it's not. But I have to support myself. I have a wife and child.

ROSS: (As Alby Grant) You don't understand. I'll get you others, ones more supple and yielding, younger than Rhonda, more voluptuous, to receive your seed and grow your pride.

GROSS: OK. (Laughter) That was my guest, Matt Ross, in a scene from...

ROSS: I think that was...

GROSS: ...the HBO series "Big Love." Yeah, go ahead.

ROSS: Oh, I think that was with Kevin Rankin, if I remember correctly, if that's the scene, who's a great actor.

GROSS: So we find out in the first season of "Big Love" that your character, Alby, is attracted to other men, which is so...

ROSS: Which I didn't know, by the way.

GROSS: Yeah, that's what I wanted to ask you. When did you find out and how did it change your impression of the character that you were playing?

ROSS: I think I read it at the table read. I think the first scene where I was wondering about his sexuality was when he picks up a drifter or a hustler in a convenience store and he takes him home. And that was just obviously a strange thing to do. I mean, well, why is he doing that? That was not clear. And his behavior that was written, the dialogue was very odd and very disconnected. And then when the - when the hustler is finally saying, well, you know, are we having sex? What's going on here? It was scripted differently than how I ended up behaving, and I think the script said that he howls like a wolf. And the director - I came to the director and said I don't really know what that means. What if I do something completely different? What if - I mean, I think, you know, Alby is - put it - this is a - he's confronted and doesn't know what to do.

And I think it's - he's terrified. And what if he just starts slamming his head against the wall? And in a way, it sends the hustler from the room. The hustler's completely confused, and then you're not sure if that was some kind of - I don't know - psychotic break or if it was intentional. And we tried that and we did it. And at the time, I remember thinking, well, I don't know if he's homosexual or if he's just the kind of person who's been so isolated that he puts himself in incredibly dangerous situations because he wants to feel something, that he's so numb he feels nothing. And I thought - I actually - at that time, I remember thinking, well, maybe it's just that. And then the next season I think I read a scene and it could've been that same season but I believe it was the next one where I read a scene where it said Alby is - I think he'd been arrested for doing something. And he was in a police station. And it said Alby is checking out all the butts of the cops that are there. And I was like, OK, well, OK, if he's checking out their butts then he's, you know, this is his sexuality. And that was the first inkling I had.

GROSS: Matt Ross, thank you so much for coming on FRESH AIR.

ROSS: Thank you.

GROSS: Matt Ross wrote and directed the new film "Captain Fantastic." He co-stars in the HBO series "Silicon Valley" as Gavin Belson, the CEO of the tech giant Hooli. And he co-starred on HBO's "Big Love."

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

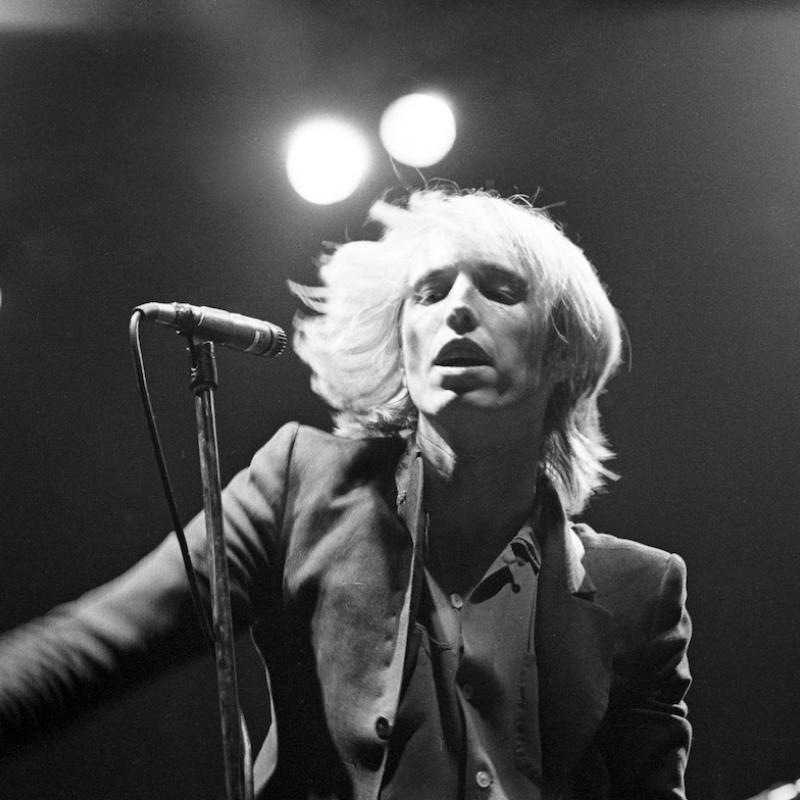

This is FRESH AIR. We're going to remember Elvis Presley's first guitarist and first manager, Scotty Moore. He died Tuesday at the age of 84. Moore played with Elvis from 1954 through 1964, then reunited with him for Elvis's 1968 comeback special. He gave up the guitar for about 25 years before returning to music.

As Peter Guralnick, the author of the definitive biography of Elvis writes, (reading) guitar players of every generation since rock began have studied and memorized Scotty's licks, even when Scotty himself couldn't duplicate them. We're going to hear the interview I recorded with Scotty Moore in 1997 after the publication of his memoir about his years with Elvis called "That's Alright, Elvis."

The title is a reference to Elvis's first single, "That's All Right," which was recorded in 1954 for Sam Phillips' label Sun Records and featured Scotty Moore on guitar.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "THAT'S ALL RIGHT, MAMA")

ELVIS PRESLEY: (Singing) Well, that's all right, Mama. That's all right for you. That's all right, Mama, just anyway you do. That's all right. That's all right. That's all right now, Mama, anyway you do. Well, Mama, she done told me, Papa done told me too, Son, that gal you're fooling with, she ain't no good for you. But that's all right. That's all right. That's all right now, Mama, anyway you do.

I'm leaving town, baby, I'm leaving town for sure. Well, then you won't be bothered with me hanging around your door. But that's all right. That's all right. That's all right now, Mama, anyway you do.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

GROSS: When you recorded this, Scotty Moore, did you have any sense that this was something new and exciting that was happening, this was the beginning of something important?

SCOTTY MOORE: All of us knew when we listened to it that it was different. But we didn't know what direction 'cause it was a R&B song and with an instrumentation coming through it into more of a country flavor. So it was a mixture. And...

GROSS: And what you're playing there is really very jazz influenced.

MOORE: Well, yes and no. I'm trying to - I had just been turned on to Chet Atkins with his thumb finger playing a few months back. And I'd been trying to figure out how he did that. It sounded like two guitars. And I was beginning to understand it, but I couldn't do it. But then I started doing the rhythm thing on this to just try to fill it up.

And as the three, four takes went on, I kept trying to stab the little notes in as I was doing the rhythm.

GROSS: Those little high notes that you're talking about?

MOORE: Yeah.

GROSS: Yeah, I mean, you know, those high notes that you play in the fills are so unexpected in a rhythm and blues song, I think.

MOORE: Yeah, they would have been, right.

GROSS: They're kind of delicate for that.

MOORE: Sneaky.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Sneaky, I like that. That's interesting too that here's, you know, this, like, really early rock 'n' roll record - there's no drummer on it.

MOORE: No...

GROSS: I mean, you know, drums are, like, the back beat of rock 'n' roll and everything. And you're starting off without a drummer.

MOORE: Well, Sam used to build slap, and then he would add the tape delay on top of that, which gave it a - the rhythmic thing also. But he always said, oh, he hated drums. He hated drums. And when I got a little more in tune...

GROSS: Sam Phillips was saying he hated drums?

MOORE: Yeah, but after I got a little more into the engineering savvy, it was a small - the room's not much bigger than this. And he couldn't control them. That's why he didn't like them.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Now, what were your thoughts about Elvis' guitar playing?

MOORE: He was a wonderful rhythm player as far as, you know, as an acoustic, open type rhythm. He had great rhythm and had great rhythm in his voice. If you listen, he did a lot of things with his voice that just came natural to him. I think he got that through the gospel influence, you know, the well, well, wells and that type of thing, especially the bass singers would do in gospel music.

GROSS: Now, tell me the truth, after you started recording with Elvis, did you think, this guy's a great singer? Or were you thinking, this guy's OK?

MOORE: Oh, well, we became more aware after just three records that he liked a challenge. But he was very particular about songs. He had to get into them, feel them good. Now, true, most of the stuff on Sun was - it wasn't original material. There were some that were remakes of R&B and some - couple of country things like "Milkcow Blues" and things like that.

But when we went to RCA, things changed. He was absolutely picking his own material then. And we'd go into the session and have a stack two feet high of acetates. And the first couple hours, he would spend going through those. And he might listen to eight bars and zap across the room. Then he'd listen about half way and he'd put that in another stack to come back and listen to again.

GROSS: This is - what? - demos that had been made for him?

MOORE: Demos, right. And that's the way he did it.

GROSS: Now, you ended up booking and managing Elvis in the early days of his recording career when he first got started at Sun Records. Did you actually have to do any of that booking yourself early on?

MOORE: Yes, I did quite a bit the first, I'd say, six months or so, yeah.

GROSS: So tell me what it was like early on before people really knew who Elvis Presley were when you were trying to establish dates.

MOORE: It was rough. I mean, you know, we're talking about making, for the group, you know, $25 a night, you know, maybe driving 50 miles.

GROSS: How would you describe what Elvis and the band were doing to someone if you were trying to book yourselves into a place, a place where they hadn't heard you yet?

MOORE: Oh, well, it was almost impossible if they hadn't heard the record on the radio. I mean, how do you describe it? Here's this kid going to come out in pink pants and white stripe and white buck shoes and...

GROSS: (Laughter).

MOORE: And a New York duck haircut (laughter) in Mississippi. No, we tried to find places that they at least - you had heard him on the radio or something. And then even then, when they saw him, it was kind of shock value, you know?

GROSS: What was the first time like when you saw him that way?

MOORE: It didn't bother me, but the Sunday (unintelligible) came over to the house...

GROSS: This was before you recorded?

MOORE: Yeah, and my wife was there. And she kind of gave me the (unintelligible) sign. I thought she was going out the back door when she saw him.

GROSS: Well, how was he dressed?

MOORE: He had on a white-lace, see-through shirt and it was either black or pink slacks with a white stripe down the side. And it was just unusual for the norm. But he always loved those flashy clothes and stuff like that.

GROSS: When did you start realizing that Elvis was really catching on in a very emotional way with his fans?

MOORE: I would say that after we did the first couple of TV shows with Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey after we went to RCA. Before that, most of our shows and stuff had been all in the southeast. And there had been some, granted, that - starting to see the hysteria and so forth. But it really didn't come home to us until we did those shows, that national exposure.

Then it just seemed like the floodgates opened up, you know?

GROSS: Now, how did you feel about this? On the one hand, it was, like, really good news for the group that the singer was so popular. On the other hand, he was getting so much of the attention. Did you feel envious of the attention that he was getting?

MOORE: Oh, no, no. That never even crossed our minds. No, that, we hoped, would mean bigger paychecks, bigger paydays, you know, for everybody.

GROSS: Did it?

MOORE: No.

(LAUGHTER)

MOORE: That did grew a little bit but not very much. That's kindly what I'm saying with the title of the book. The pay raises, the perks and stuff as he got bigger and bigger and bigger didn't come along for the band. And I'm just saying, that's OK. It's not - we were being paid a fair wage as far as the man on the street with an everyday job.

GROSS: Right.

MOORE: You know, 200 bucks a week back then wasn't bad at all. But then you take - as he got bigger and we had to get in these bigger hotels and people expect you to take them to dinner. And we bought our own clothes and paid our own hotel bills out of what we were making. And we were saying, you know, hey, some of this should come from some other source, you know.

That was the thing. We weren't really arguing about that we didn't have enough to pay the bills at home. But it was all this other stuff that was really expected of you that you couldn't afford.

GROSS: We're listening to my 1997 interview with Scotty Moore, Elvis Presley's first guitarist. Moore died Tuesday. We'll hear more of the interview after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. We're remembering Scotty Moore, Elvis Presley's first guitarist and first manager. Moore died Tuesday at the age of 84. Let's get back to my 1997 interview with him.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

GROSS: What would you say is your most-copied guitar solo from the Elvis records?

MOORE: Probably "Heartbreak Hotel" maybe. I don't know. I mean, I've never been asked that before. Can we do a survey?

GROSS: (Laughter).

MOORE: Write in, folks, and tell me (laughter). I don't know.

GROSS: Well, why don't we go for "Heartbreak Hotel?"

MOORE: OK.

GROSS: Tell me your memories of this session.

MOORE: Well, of course, that was the first one on RCA. And they were trying to get basically the same sound that Sam was getting - had gotten with us in Memphis. And they had this big, long hallway out in the front that had the tile floor. So they put a big speaker at one end of it and a mic at the other end with a sing - do not enter.

And they used that - that's where it ended up with that deep, real room echo instead of the tape delay echo that Sam had used. Now, there is - it's hard to hear - there is a little tape delay on it. But either their tape machine didn't match his - and so it's just very slight. And then he ended up with just the acoustic echo.

Room echo at that point was sound effects they used in the movies. They weren't using them for recording. And then here comes this, and it's so drastic. But it worked for the song. When he says, you know, at the end of lonely street, it's so distant. One thing that Sam did that I don't believe he realized when he was doing it, and I didn't until years later that I got into engineering, he pulled Elvis's voice back close to the music.

You know, all the Sinatra and all those things where the voice is so far out in front. And he wanted us to use Elvis's voice as another instrument.

GROSS: Into the mix.

MOORE: Into the mix but didn't bury him like a lot of the rock things, you know, later.

GROSS: Right.

MOORE: But you could still - closer.

GROSS: Well, all right. Let's hear it, 1956, "Heartbreak Hotel."

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "HEARTBREAK HOTEL")

PRESLEY: (Singing) Well, since my baby left me, well, I've found a new place to dwell. Well, it's down at the end of Lonely Street at Heartbreak Hotel. I get so lonely, baby. Well, I'm so lonely. I'll get so lonely, I could die. Although it's always crowded, you still can find some room for broken-hearted lovers to cry there in their gloom.

They'll be so - they'll be so lonely, baby, they'll get so lonely. They'll be so lonely, they could die. Now, the bellhop's tears keep flowing, and the desk clerk's dressed in black. Well, they've been so long on Lonely Street, they'll never, they'll never get back. And they'll get so lonely, baby, well, they're so lonely.

They're so lonely, they could die. Well, now, if your baby leaves you, and you've got a tale to tell, well, just take a walk down Lonely Street to Heartbreak Hotel where you will be, you will be so lonely, baby. Where you will be lonely. You'll be so lonely, you could die.

GROSS: That's "Heartbreak Hotel," my guest Scotty Moore on guitar. And he's written an autobiography, which, of course, includes his years playing guitar with Elvis Presley. It's called "That's Alright, Elvis."

Did you see Elvis undergo a personality transformation as he became more and more famous, you know - a recording star, a movie star, a heartthrob, an icon?

MOORE: You know, the years I spent with him, he seemed to take it in stride. Yeah, I saw all the things changing around him, you know, with the movies and such. And he became more secluded as he gathered his entourage around him because he didn't feel like he could go out and didn't want to cause a scene, you know, just going to, you know, like, a famous restaurant or something.

But as far as personality changes and stuff, I didn't become aware of any until after I left him. And then he started in the '70s. And I don't know the inside. And I've heard, of course, and read a lot of stuff. But it still amazes me because a few months before he died, I saw some footage when he was so bloated. He just - you know, I said there's something desperately wrong because he was very vain. And there's no way that he'd go out in front of people like that.

GROSS: Did you feel like he...

MOORE: I don't think he could see hisself (ph) in the mirror at that point.

GROSS: Did you feel like you didn't recognize the person he had become?

MOORE: No, I didn't.

GROSS: Did you communicate with him at all during that period?

MOORE: No. And it was not because of any conflicts or anything. It's just that with this entourage around - and there was two, three of those guys that were really good guys. But still, he could call me a lot easier than I could get through to him. You know what I'm saying. You make the call. You don't know if he ever gets it or not. And so I just left it for him.

GROSS: Do you feel bad that Elvis died during a period when you weren't really in touch, so you didn't have a chance to maybe talk about things with him that you might have liked to talk about before he passed?

MOORE: Well, yes, in one way. But in another way, I always - he was so vain, I could never see him growing old gracefully.

GROSS: That's interesting. But, like you were saying, if he was so - like, he was so vain, and yet he managed to allow himself to balloon the way he did.

MOORE: That just astonishes me.

GROSS: Yeah.

MOORE: I don't know. I will never understand that.

GROSS: But you can't imagine an aging Elvis?

MOORE: No. I mean, if he hadn't got into that...

GROSS: Right

MOORE: ...Situation, no. I never could. In fact, the guys - we used to talk about it, you know, said - what's he going to do when he gets about 60, you know?

(LAUGHTER)

MOORE: What if he goes bald? - you know, just all kinds of stuff like that.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Well, Scotty Moore, I'm really glad you're playing again and a pleasure to have the chance to talk with you.

MOORE: Terry, it's been a pleasure and enjoyable.

MOORE: Scotty Moore, recorded in 1997. He died Tuesday at the age of 84.

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. Maren Morris is a young singer-songwriter whose first major label album, "Hero," debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard country music chart. Rock critic Ken Tucker likes how the album mixes a knowledge of traditional music with pop and hip-hop influences.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "MY CHURCH")

MAREN MORRIS: (Singing) I've cussed on a Sunday. I've cheated, and I've lied. I've fallen down from grace a few too many times. But I find holy redemption when I put this car in drive, roll the windows down and turn up the dial. Can I get a hallelujah?

KEN TUCKER, BYLINE: That's Maren Morris's big breakthrough single, "My Church." It's got the catchy twang of a hit, for sure. And there's something else interesting about the song. When Morris asks if she can get a hallelujah and an amen, she's imploring a congregation of sainted country stars such as Hank Williams and Johnny Cash.

The lyric is about driving down the highway, singing along to the radio and feeling, as she says, that that's my church. So we'll have to put Morris down for the moment as a religious agnostic with a leaning toward the mega-church of hardcore country and capitalism.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "RICH")

MORRIS: (Singing) If I had a dollar every time that I swore you off and a twenty every time that I picked up when you called and a crisp new Benjamin for when you're here then gone again and a dollar every time I was right about you after all, boy, I'd be rich, head to toe Prada, Benz in the driveway, yacht in the water, Vegas at the Mandarin...

TUCKER: That's "Rich," in which Morris folds in references to how many Benjamins she's spending on name-checked fashion brands and tossing in phrases such as me and Diddy dripping diamonds like Marilyn. That is indeed a bit rich and would be obnoxious if the music surrounding it wasn't so disarming.

And the music is very good state-of-the-art pop-country, as on the album's second single, "80's Mercedes." It comes on like a propulsive track from Fleetwood Mac before bursting into full power ballad mode by the time she hits the chorus about being, quote, "a '90s baby in my '80s Mercedes."

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "80'S MERCEDES")

MORRIS: (Singing) Still runs good, built to last. Moves like a hula girl on the dash. She ain't made for practicality. Yeah, I guess she's just like me. It's Saturday night, about time to go. Got my white leather jacket and a neon soul. Once I turn on the radio, I'm ready to roll - ready to roll.

Feel like a hard-to-get starlet when I'm driving, turning every head - hell, I ain't even trying. Got them Ray-Ban shades pretty in pink. Call me old school, but hey, I'm a '90s baby in my '80s Mercedes. I'm a '90s baby in my '80s Mercedes.

TUCKER: Morris came to Nashville via Texas. And once she arrived in Music City, she worked as a songwriter, placing songs on albums by stars such as Tim McGraw and Kelly Clarkson. She put out three albums independently before getting signed to Columbia Nashville.

What Morris brings to her genre is a very fluid sense of musical boundaries. Two songs in particular make this case for me. The first is "Just Another Thing," a very nice medium tempo bit of R&B-pop with an excellent country music chorus phrase - you're just another thing I shouldn't be doing.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "JUST ANOTHER THING")

MORRIS: (Singing) I ought to know better, but you know that never stopped me before. Yeah, my wheels just have a way of spinning, always ending back at your door. So add your name to the list. Of all the things I can't seem to kick - you're just another mess, another late night call I shouldn't be making, just another high, another one-night shot I shouldn't be chasing.

I got my excuses. No, I don't know why I do it. But you're just another, just another thing I shouldn't be doing.

TUCKER: The other example of Morris's range is my favorite song on the album. It's also one of her most considered - the moment she slows down, calms down and takes the image she spent the album building of herself back down to human scale. The song is "I Wish I Was," which, with its slow groove chorus and slide guitar, sounds like a song Bonnie Raitt might have recorded on one of her early albums.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "I WISH I WAS")

MORRIS: (Singing) On paper, we go together. I know that we look the part. But almost never hangs on forever. I know I'm breaking your heart. So go on, say what you want to. I'm not gonna stop you. You can blame it all on me. I'm not the hero in the story. I'm not the girl that gets the glory 'cause you're looking for true love, and I'm not the one. But I wish, but I wish I was. I wish - oh, I wish - I was.

TUCKER: It's too early to tell how much staying power Maren Morris has. But this album, "Hero," suggests someone whose interest in country music is most tied to the genre's opportunities to explore the strains placed on relationships, family and faith in oneself.

She may well be using country as a leaping off point for a pop career, in the recent example of Taylor Swift. Or maybe she's trying to figure out how to be a more worthy acolyte, serving on the altar of Hank Williams and Johnny Cash.

GROSS: Ken Tucker is critic-at-large for Yahoo TV. He reviewed Maren Morris's new album, "Hero."

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.