Looking Back on Metallica at a Moment of Crisis

Guitarist and vocalist James Hetfield founded the popular metal band Metallica. Hetfield co-writes many of the band's songs, a force on the heavy metal scene since the 1980s. In 2004, the movie Metallica: Some Kind of Monster captured the band at a time of crisis, when their bass player quit and the group hired a "therapist and performance-enhancement coach" to help them sort things out. Also, Hetfield entered rehab during the filming.

Other segments from the episode on August 29, 2007

Transcript

DATE August 29, 2007 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Rob Halford discusses his heavy metal band Judas Priest

and CD "Angel of Retribution"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Crank up the volume because today we begin our holiday weekend series on hard

rock and heavy metal.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: As the lead singer of the British heavy metal band Judas Priest, my

guest Rob Halford became famous for his powerful voice, the leather studs and

handcuffs he wore on stage, and the way he often made his stage entrance on

his motorcycle. Judas Priest is one of the originators of heavy metal and one

of the most theatrical and successful bands in the genre. Famous for such

songs as "Hell Bent for Leather," "Ram It Down," "You've Got Another Thing

Comin'," and this one from 1980 "Breaking the Law."

(Soundbite of "Breaking the Law")

Mr. ROB HALFORD (Judas Priest): (Singing) There I was completely wasting and

out of work and down. All excited, so frustrating, had to drift from town to

town, feeling as though nobody cares if I live or die. So I might as well be

dead, but the future's in my way. Breaking the law, breaking the law.

Breaking the law, breaking the law. Breaking the law, breaking the law.

Breaking the law, breaking the law.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Some parents took Priest's evil boasts at face value. The parents of

two young men sued the band, claiming one of their records convinced the young

man to commit suicide. In 1990, the judge ruled in favor of the band.

Rob Halford started singing with Priest back in 1971. He left the band in the

early '90s and later surprised his fans by coming out. Being gay sure didn't

fit the stereotype of the heavy metal god. Halford returned to Judas Priest

in 2003. I spoke with him in 2005.

So what's it like, more than 30 years after you started in Judas Priest, to

be, you know, putting on the costumes again, the leather and, you know, the

studs and the collars and all the stuff...

Mr. HALFORD: Well...

GROSS: ...and then to be singing these kind of...

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah.

GROSS: ...these anthems that were like teen-age anthems of defiance...

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah.

GROSS: ...for your audience?

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah.

GROSS: But so many people who were your fans early on are probably in

positions of authority themselves now. I bet there's a lot of...

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Really, I bet there's a lot of, like, cops...

Mr. HALFORD: That's true. No, that's very cool.

GROSS: ...who were your fans and teachers who were your fans and...

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah. Well, the--you know...

GROSS: ...parents who were your fans.

Mr. HALFORD: Yes. Yup. Absolutely. And you've just named three parts of

society which attend frequently Judas Priest shows. I have friends...

GROSS: And used to be terrified of you, right? Like, this was a bad era...

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah. Well, maybe so. Exactly.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. HALFORD: You wouldn't believe the amount of law enforcement that loved

Judas Priest, especially here in New York City. And here we are, a band that

wrote this song called "Breaking the Law"...

GROSS: Right. Exactly.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. HALFORD: ...you know, which is quite remarkable. But I think beyond

that, there's this incredible bond that is maintained with our fan base

internationally.

GROSS: One of the things that has changed is that you're out now. And this

is the first time you're performing with Judas Priest since you've been out.

Mr. HALFORD: Hm.

GROSS: And do you think that changes anything for you and the band or changes

the way your audience sees you?

Mr. HALFORD: Well, I think it destroys the myths of, you know, the so-called

intolerance and homophobia that was supposedly existing in heavy metal.

Having said that, I think that if I'd have done this earlier, in the '70s or

the '80s, things may have been a bit more difficult. But that's kind of a

debatable question because we never really confronted the issue at that time.

I wanted to do it for myself, like any gay man or lesbian woman and anyone

that wants to, you know, bring this forward. And my proclamation is it's what

you're entitled to; it's your own right, so to speak. But I was always

protective of Judas Priest. I always felt that had I have done this any

earlier or had I've done it in different circumstances, the fallout would have

damaged the band. And I would never do anything to hurt the band or its

reputation or its following.

So I think that, you know, the timing was right. And just for me personally,

it was a great moment of release.

GROSS: You know what I love about the fact that you did come out is I think

for so many teenage boys, heavy metal is not only about the music. It's

about, you know, these fantasies of, like, orgies with women, you know, and

having all the women...

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: ...and how you're going to treat the women...

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah, the sex and drugs and rock 'n' roll thing. Yeah.

GROSS: Yeah. And, you know, if nothing else, it's like your coming out

really complicates all of the cliches about, you know, the sex part of the

sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll.

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah.

GROSS: And it takes it out of this kind of simplistic, sometimes misogynistic

fantasy that I think teenage boys have.

Mr. HALFORD: Exactly. Well, without laboring on one element here, just the

teenage boy element--because, of course, the thing about Judas Priest's music

is that we're not the same as every other heavy metal band. I think we've

created our own niche, our own particular stamp...

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. HALFORD: ...identity, trademark, whatever you want to call it. And if

you look at the broad catalog of this band's material, some hundreds and

hundreds of songs over a three-decade span, I think that that's just one,

really, one small focus of area...

GROSS: Well, a lot of your songs have this kind of, like, mythic quality to

it.

Mr. HALFORD: Yes, they do.

GROSS: Like, even the song "Hellrider," which we opened with...

Mr. HALFORD: Yes.

GROSS: ...from the new CD--I'm just going to--forgive me as I read some of

the lyrics. I'm not...

Mr. HALFORD: Please do. Please do.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. HALFORD: Go ahead.

GROSS: OK. `Hellrider, hellrider, you slaught them all extinguished, wrath

of doom in killing fields, they consume for valiants never yield.'

Mr. HALFORD: Yes.

GROSS: `Triumph to the gods vanquished...'

Mr. HALFORD: Yes.

GROSS: `...of enslavers.'

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. HALFORD: Absolutely. Well, there you go.

GROSS: It's like overblown, mythic language.

Mr. HALFORD: Isn't it wonderful? It's wonderful. But you see what the

overriding story is there? The overriding story is of optimism. And the

overriding story is of defeating anything that stands in your way, that

prevents you from achieving your goals or your dreams. And...

GROSS: But this has really, like, archaic language.

Mr. HALFORD: Oh, it does.

GROSS: You `slaught them all.'

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. HALFORD: Ah, but that's because I love to--I love the English language.

My favorite book is a thesaurus, you know.

GROSS: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Mr. HALFORD: I'm constantly looking to find words and language that some

bands would maybe hesitate to use or they're not able to because of the arena

that they work in.

GROSS: Now there's the Judas Priest sound; there's also the Judas Priest

look. And, I mean, you were one of the creators of that look--of wearing, you

know, the leather and the studded collars and the handcuffs and the choke

chains and, I mean, all the stuff that almost looks like fetish gear.

Mr. HALFORD: Well, it is, to some extent...

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. HALFORD: ...although maybe not so much now because...

GROSS: Because it's a genre now. It's...

Mr. HALFORD: Well, no, it's because I can spend some money on some outfits,

whereas before I had to go into the local S&M shop and pick up something for 2

pounds.

GROSS: Oh!

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. HALFORD: That's the truth of it all. Yeah, I used to go down to my

local--used to S-shop in London and put 10 quid down and try and grab a little

bit of this and little bit of that and slowly put it together, you know. But,

yes, we're--again, it's something that we're very proud of. For a number of

the early formative years of metal, the image was not really tying in to the

fierceness and the strength and power of the music. And we kind of stumbled

upon it with a song called "Hell Bent for Leather," which is very much a biker

anthem song. We actually started to use the motorcycle at that point, too.

So all of these things kind of connected and created the heavy metal look.

So, yes, blame us for that.

GROSS: And this isn't meant to be as personal as it's going to sound, but was

all the leather and handcuffs and fetish gear an expression of your personal

lifestyle or just good theatrical costuming?

Mr. HALFORD: Well, that's a very good question. I'm sure if there was a

couch here for me to lay on and a psychiatrist...

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. HALFORD: ...he'd probably go, `Yep, that's what you were doing, Rob.'

Who knows? I don't know. As I said, it was never part of a deliberate intent

for me. But, yeah, I would hasten to say--because you're the first person

ever to ask me this question--that subconsciously that was my way of saying,

`Look, this is who I am.' But, you know, in my outward kind of conscious

level, that was never a thought because that would have meant that I would

have been using the band and my look for some kind of agenda, which I've never

had.

GROSS: When you say that it was in some ways a level of who you were, so was

it like a fantasy level of who you were or...

Mr. HALFORD: Oh, yes. Yes. Well, I don't know. This is just kind of an

open, free-forming kind of thought here. No. I mean, I'm not particularly

attracted to that world or that fantasy element of what that lifestyle

presents. It's just of no interest to me personally. It's all about, in all

honesty, the fact that putting all that stuff on and looking at yourself in a

mirror before you went on stage felt absolutely the right thing to do.

GROSS: Well, since you've mentioned "Hell Bent for Leather," I think we

should hear it. So this is Judas Priest, "Hell Bent for Leather."

(Soundbite of "Hell Bent for Leather")

Mr. HALFORD: (Singing) Seek him here, seek him on the highway, never knowing

when he'll appear. All await, engine's ticking over, hear the roar as they

sense the fear. Wheels! A glint of steel and a flash of light! Screams!

From a streak of fire as he strikes! Hell bent, hell bent for leather. Hell

bent, hell bent for leather. Black as night, faster than a shadow, crimson

flare from a raging sun.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's Judas Priest, the band's lead singer Rob Halford will be back

after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: My guest is Rob Halford, the lead singer of Judas Priest, one of the

originators of heavy metal.

Judas Priest shows are quite theatrical experiences. How did you head in that

direction of making it, like, theatrical?

Mr. HALFORD: Well, it just comes from being a kid, you know. I mean, when I

was in my early grades at school, I was able to get into the school choir and

be a part of all of the school productions, much like a lot of kids do. And I

just ran to that. It made me feel good inside. So there was a point in my

life when it was kind of a toss-up between whether I was going to actually go

from school--high school--into drama school and drama university in England.

But I chose to go with music because that was the love of my life at that

time, and it still is today. So I think I brought that theatrical desire with

me to Priest. And I was always, you know, at the band meetings pushing for

this lighting effect or that stage set or these costume ideas or these smoke

machines or, you know, pyrotechnics, whatever it might be. Whatever is really

theatrical came from my love of the theater and the magic that it can make.

GROSS: For listeners who haven't seen your show, can you describe one of the

most theatrical things?

Mr. HALFORD: We have a moment going on in this current "Angel of

Retribution" worldwide tour that we do.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. HALFORD: There's an opening cut from "Angel of Retribution" called

"Judas Rising," and I appear behind the drum riser on a 50-foot hoist, a

pneumatic man lift. And at the bottom of the hoist is this theatrical flame

fire effects. And so there's an intro--there's a piece of intro tape that

works with that song, and the man lift, as it's called, is being taken up to

about 50 feet. And there's all of this smoke and fire billowing around my

feet, and I'm wearing this outfit made out of pure reflective chrome and hit

with, you know, two or three spotlights against a backdrop of this

larger-than-life, 100-foot-wide reincarnation of the "Angel of Retribution"

artwork. And it's absolutely spectacular. I mean, I can see the reaction as

that all comes together, and that's just one element of a two-hour Judas

Priest performance that the fans love.

GROSS: Is there part of you that stands back and says, `God, this is really

funny'? Do you know what I mean?

Mr. HALFORD: Honestly, you've got to have a "Spinal Tap" mentality.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. HALFORD: "Spinal Tap" helps, yeah, because, you know, you've got to be

able to laugh at some of these things and smile and enjoy them, which is not

to kind of take it as a joke or to humiliate it. But you've got to certainly

be able to kind of smile at some of these things that you do but in a loving

way, in a way that you're cherishing the moment. And you know the effect that

it's creating and how it's making you feel yourself as you bring that effect

to life. But, yes, certainly every band has a copy of "Spinal Tap" on the

tube or...

GROSS: So at its best, what does it feel like to come, you know, rising out

from--on this, like, hydraulic lift in your chrome costume with spotlights

shining on you? Like, what does that feel like on a really good night?

Mr. HALFORD: Well, I'll tell you what it feels like, Terry. It feels like,

`I hope the lift doesn't jam. I hope the smoke machine doesn't blow up. I

hope my microphone works at this height.' That's what it feels like.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. HALFORD: It's a complex run of emotions right up till I start singing

the song, but once the song is in full roar, it's just a very powerful,

dominating type of explosion that goes on for the duration of the song. It's

a very powerful song for us to perform because I think it embodies a lot of

the reunion aspects that we're still enjoying right now.

GROSS: So are there moments in performance now where you feel, `I am a heavy

metal god'?

Mr. HALFORD: Oh, yes. Every time I get dressed before I go on stage, and I

think that I can say that in all honesty, that doesn't mean to say that I'm a

schizophrenic or a split personality. But definitely when you get dressed to

go to work, your persona changes. You're getting psyched up. Your attitude

is being prepared mentally. And much like a boxer going into the ring or a

basketball player going out to court, you know there's a job to be done with

your teammates, and you're going to win. And so definitely there's a feeling

of confidence and a certain makeover that takes place.

GROSS: Now, you know, with Judas Priest titles like "Hellion," "Eat Me

Alive," "Devil's Child," "Breaking the Law," "Screaming for Vengeance,"

"Beyond the Realms of Death," "A Touch of Evil," "Sinner," we can all see why

parents in the '70s and '80s weren't necessarily thrilled that their children

were listening to your records. What effect do you think your music has had

over the years on your teenaged fans?

Mr. HALFORD: Well, our teenaged fans have grown up now, and they're healthy,

stable, balanced, family-oriented fans. They bring their children to our

concerts. So if that isn't proof that Judas Priest has stood by nothing other

than giving people some escape and some great nights out when they see us

live, and some very personal enjoyment at home on the headphones or on the

speakers, then I don't know what else to say. I'm at a loss for words. It

kind of puts to sleep that moment in the '80s when this--not only this band,

even individuals like Sheena Easton were attacked by a political agenda that

really had, in our opinions, some misconceptions.

There was the one side of it about protection, which was running very close to

censorship. But we all approved this PG rating. We thought it was a great

idea because some of us were using language and ideas that we felt it was

important to attach some kind of notification towards. But those songs that

you mentioned are but a handful of some, I don't know, two, 300 recordings

that we've made over the years. Little things pop out more than others, and

things get more attention than others.

GROSS: I want to get back to something we were talking about a little earlier

which is coming out, and what year was it that you actually came out?

Mr. HALFORD: Do you know, I can't be absolutely precise. I would think it

was around '93, '4.

GROSS: OK. I imagine there were a lot of times when you were in a really

awkward position. I mean, for example, most bands have groupies. I'm sure

there were so many women waiting for you, you know...

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: ...actually throwing themselves at you, and, you know...

Mr. HALFORD: (Coughs) Excuse me.

GROSS: ...how do you make it clear that, like, you know, `No thanks'?

Mr. HALFORD: Well, that's it. I mean, I'm a very polite British gentleman.

`No, thank you.' It's as simple as that, and I'm kind of proud of that. I'm

very proud of myself that I didn't go out onto this kind of extreme limb of

displaying myself in a way that was not truthful, which is to say that, you

know, I wasn't caught in those kinds of situations just because I felt it was

important to portray myself in a certain way, being a singer in a famous

heavy-metal band. You know, I couldn't do that, because again, I would have

been using myself, I would have been using a lot of different things that go

against my own particular standards. So, yeah, you say, `No, thank you,' you

know, and leave it at that.

GROSS: Did you feel cut off from other gay people? Because if you felt you

couldn't come out, it probably meant you couldn't hang out with a gay crowd

and...

Mr. HALFORD: Ah, yes.

GROSS: ...so, like, you know, what do you do when you're on the road? Who do

you...

Mr. HALFORD: Well...

GROSS: ...hang out with?

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah, again, this is all about surroundings and circumstances

in it because that was a world that I didn't really walk towards or begin to

investigate until I was probably in my mid-20s or so, which might sound

amazing to some people, but it never really interested me. I'm still--I'm a

conservative gay man and, you know, bars don't interest me, clubs don't

interest me. I'm still to some extent invisible within the gay community and

that's because I don't really seek to be, you know, a spokesperson for

whatever things are being discussed by other celebrities. By walking out,

night after night, in front of thousands of metal fans all over the world as a

gay metal singer, that, to me, is my cause and my moment for celebration.

GROSS: Rob Halford is the lead singer of Judas Priest. Our interview was

recorded in 2005.

Our hard rock and heavy metal series continues in the second half of the show.

I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of "You've Got Another Thing Comin'")

Mr. HALFORD: (Singing) One life, I'm gonna live it up. I'm takin' flight; I

said, `I'll never get enough.' Stand tall, I'm young and kinda proud. I'm on

the top for as long as the music's loud.

(End of soundbite)

(Announcements)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

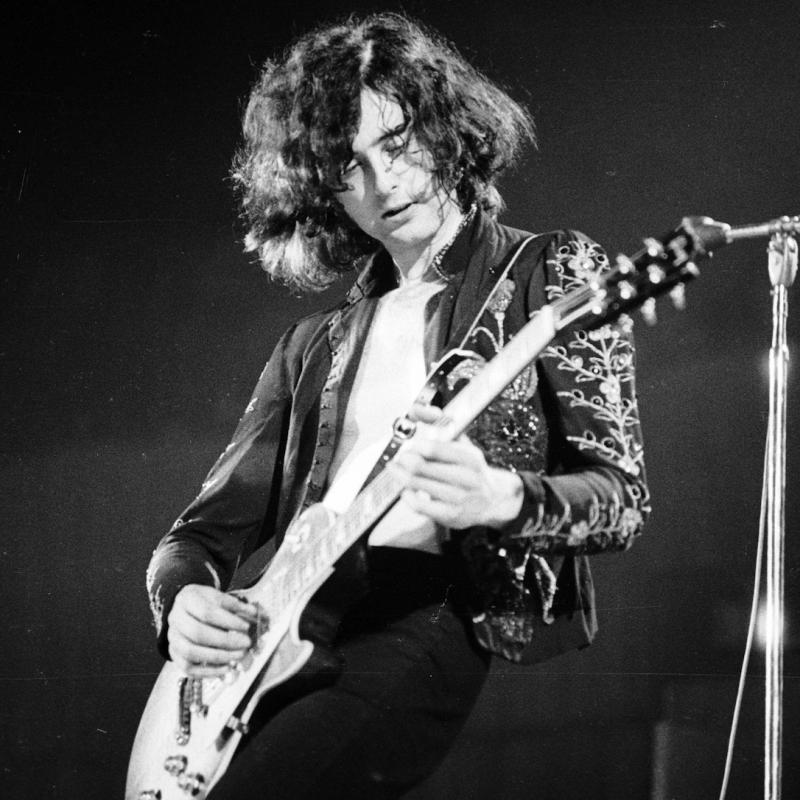

Interview: Metallica singer James Hetfield talks about his career

and life

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

The band Metallica, the biggest-selling rock act of the '90s, has survived for

over 25 years. My guest is singer and guitarist James Hetfield, one of the

founders of the band. As "The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock 'n' Roll"

says, "After gaining a solid cult following among fans who could not identify

with contemporary, pretty-boy pop-metal combos, such as Van Halen and Bon

Jovi, Metallica became known for its sophisticated, often complex song

structure and serious lyrics that reflected teen obsession with anger,

despair, fear, and death."

I spoke with Hetfield in 2004, the year that the documentary about the band

was released on DVD. That film, "Some Kind of Monster," chronicled the making

of their album "St. Anger" and the anger, tension, and exhaustion that nearly

broke up the band as the members neared middle age. The band actually hired a

therapist to do group therapy sessions. During this period, Hetfield checked

himself into rehab. When he emerged, Metallica completed "St. Anger." Here's

a song from it called "Some Kind of Monster."

(Soundbite of "Some Kind of Monster")

Mr. JAMES HETFIELD: (Singing) These are the legs in circles run. This is

the beating you'll never know. These are the lips that taste no freedom.

This is the feel that's not so safe. This is the face you'll never change.

This is the god that ain't so pure. This is the God that is not pure. This

is the voice of silence no more. Some kind of monster. Some kind of monster.

Some kind of monster. This monster lives. This is the face that stones you

cold.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: James Hetfield, welcome to FRESH AIR. Let's start at the beginning of

Metallica's history. What did you want Metallica to be?

Mr. HETFIELD: Oh, boy. I wanted it to be freedom from school, from work,

from the typical music that we were hearing. But really it was--music was

somewhat of an escape for me that turned into a really great gift eventually.

But it was a way to get away from my screwed-up family that I felt...

GROSS: What was screwed up about your family?

Mr. HETFIELD: Well, no one really communicated very well. It was very

insular, very--somewhat elitist in our religion. You know, `Oh, that's what

they believe, but we believe this, which is better, you know, which is

Christian Science.' I grew up in that type of atmosphere. And I never really

understood it, either, so I felt fairly alienated from the outside world and

from my family. So it was a connection--music, for me, was. But

Metallica--when we hooked up, we were just passionate and loved music, and it

was the soundtrack for our lives, you know. It spoke for us.

GROSS: And how old were you when the band started?

Mr. HETFIELD: Let's see, fresh out of high school, so 18 or 19 we started.

GROSS: So no college?

Mr. HETFIELD: No. We had college on the road basically. Street college.

GROSS: So you said that music was also an escape from work. Was this an

escape from the work that you would have been doing had you not been in the

band, or were you already working?

Mr. HETFIELD: Well, I was working. And my dad left a note saying he was

leaving, at age 13, never really said good-bye. My mom passed away at 16. I

went and lived with my older brother, and she left some inheritance for me,

but it was so tough to even want to touch that. I didn't--it was like that

was still Mom. I didn't want to mess with that, so I went and I got a job

working at a high school, moving a high school, then it was custodial work,

then I went working in a factory, because I had the long hair. That was

pretty much all I could get. Oh, it was so frustrating just sitting there.

It was OK. At lunch, I'd go out and write in my truck, write some songs.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. HETFIELD: But I remember seeing this older guy working as the foreman,

you know, `One day you'll be foreman,' you know.

GROSS: Ugh.

Mr. HETFIELD: Ooh, joy, you know. And he's--I don't know--40, 50 years old,

and it's like, `Man, I cannot do this. I have to play music.' It was in me.

I knew that it had to happen.

GROSS: Now I don't think you ever got into the kind of "Spinal Tap"-type of

show-bizzy, you know, heavy metal stuff with the breastplates and the

codpieces, right? I mean, you never were into that, right?

Mr. HETFIELD: Well, under my jeans, yes.

GROSS: Under your jeans, yes.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. HETFIELD: Well, we did some tours with the band...

GROSS: You're more like T-shirts and jeans.

Mr. HETFIELD: Basically.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. HETFIELD: Yeah, we would walk on stage and play with what was

comfortable, you know. Wearing a spiked wristband with, you know, nails

sticking out of it didn't--you know, you really couldn't wipe your forehead

off with that, you know. It wasn't comfortable. You know, at the end of the

day, we wanted to be, you know, just us. And, you know, we had done some

tours with bands--and growing up in LA, it was kind of everywhere, and there

was a little bit tried to sneak in, you know. I had bullet belts, you know,

because Lemmy from Motorhead had that. That was the extent of our dressing

up, you know, but...

GROSS: Did you have your destructive period of destroying hotel rooms and...

Mr. HETFIELD: Oh, yeah. Oh, definitely. A lot of our early lyrics were all

about that, you know, on the road, show up in a city, rape, pillage, move on,

you know.

GROSS: Now what's your explanation for why you wanted to do that?

Mr. HETFIELD: Oh. Because I guess we could. Because I guess we were angry.

We needed attention and partly because you were supposed to, you know. We'd

heard about, you know, the decadence of the '70s bands, you know, going in,

and they had orgies, they had--you know, they were throwing TVs out at--you

know, you heard all those stories, and we didn't really throw any TVs out of

windows, but we jumped out of windows into pools, breaking bones, you know,

setting off hotel alarms at 4 in the morning and having to pay for everyone's

room, you know, things like that, you know, kicking holes in the walls,

whatever, all kinds of just, you know, kind of releases.

And after a while, it became a trap, you know. You're on tour paying for your

destruction, you know, and you're not bringing any money home, so...

GROSS: Did you enjoy it? Did you enjoy destroying things?

Mr. HETFIELD: There was something about it, and I don't know. I tie it in

with my anger a lot. And I had a lot of anger and rage problems that would

just overcome me, and I would--whatever was near, I'd throw it and it would

break. And it was just this adolescence that stuck with me, you know. And,

you know, when I finally started, well, dating my wife-to-be, who is my wife

now, Francesca, you know, it was embarrassing. It was embarrassing to myself

and to her, and she helped me grow up quite a bit. But, yeah, there was

something about smashing stuff that just felt right. It felt good.

GROSS: Now do you think that anger worked for you musically?

Mr. HETFIELD: Oh, completely.

GROSS: Yeah?

Mr. HETFIELD: I do now.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. HETFIELD: At the time, we didn't analyze anything. It was just going

for--it was going with the heart, is what we called it, you know. It was

whatever was coming out at the time.

You know, I can't change what has happened, you know. Everything that has

happened in our career, you know, as far as angry lyrics or whatever it was

coming out, you know, subliminally even, that happened for a reason. It all

happened for a reason for us to get where we are now, to realize, wow, we were

very immature, in a way, but writing about it, you know, not knowing how to

grow up or how to change your survival techniques or your tools in life, how

to relate to people. And, you know, it took the band almost breaking up to

realize a lot of things, and one was our form of expression, what a gift we

have in that.

And, you know, after getting clean and sober, going back and reading a lot of

the lyrics, going, `Wow, that's pretty intense, and I can't belive there's

some fans out there that really like this, you know.'

GROSS: Give me an example of what you're thinking.

Mr. HETFIELD: Well, something like "Dyers Eve." This is a song about my

parents and how they've kept me in a cocoon, you know, not allowing me to see

the world, of what different religions there were or different kinds of

people. Or, you know, for me, learning about other things was not--they were

trying to keep me in almost like a cult type of religion...

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. HETFIELD: ...it felt like to me. And this song talks about, you know,

`Now that you're gone, I'm out here in the world and lost and I'm scared and,

you know, I blame you, I blame you completely,' and a lot of blame put onto my

parents, you know, at that point, and it's pretty heavy stuff when I read it

now. You know, but I realize my parents were doing the best they could with

what they had to work with, you know. I didn't realize the trickle-down

effect from their parents, you know. You know, you look at your parents

as--they're gods in a way, you know. They could never do wrong, you know.

But looking back and realizing that, yeah, they made some mistakes, but they

did the best they could and let me sort out those mistakes and try and not

repeat them.

GROSS: Well, why don't we hear that song? This is Metallica.

(Soundbite from "Dyers Eve")

METALLICA: (Singing) Dear Mother, dear Father, what is this hell you have put

me through? Believer, deceiver, day in day out live my life through you.

Pushed onto me what's wrong or right, hidden from this thing that they call

life. Dear Mother, dear Father, every thought I'd think you'd disapprove.

Curator, dictator, always censoring my every move. Children are seen but are

not heard, tear out everything inspired. Innocence torn from me without your

shelter. Barred reality, I'm living blindly.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: OK. So that song speaks a bit about your parents. You know, your

mother's died, your father's still alive?

Mr. HETFIELD: No, he's passed away. He passed away about 12 years ago or

so.

GROSS: Mm. Did you write this before he died or...

Mr. HETFIELD: Yes. Mm-hmm.

GROSS: What did he think when he heard it?

Mr. HETFIELD: I don't know and I really didn't care.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. HETFIELD: We didn't connect again for a long time.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. HETFIELD: And it was somewhat difficult trying to figure out, `What is

this relationship? Am I supposed to hate him still? You know, he's my dad.

I love him, but, dude, I mean, you screwed us over. You left, took all our

money, enough that my mom couldn't survive, and she worried herself sick and

eventually died and kind of was left hanging.' And a lot of the stuff I was

mad about was really him not teaching me how to be a man or a boy or whatever

it was, and I had to figure it all out by myself I felt, you know. And I

wasn't ready for it. But I worked a lot of that anger out in some therapy

things, which was really helpful. But, yeah, you know, our relationship was

very strange. After he left, it devastated me, you know. Well, he came back

probably six months to a year later and he was, you know, he was a midlife

crisis dad, you know, had the Stingray and the funky haircut, he shaved. And

who's this guy, you know? Bringing me gifts from Europe, you know, and

Hawaii, and meanwhile, we're struggling, you know.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. HETFIELD: So we had a strange relationship, eventually got to be

somewhat friends again, but it was never resolved. This stuff was never

resolved.

GROSS: My guest is James Hetfield of Metallica.

We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: Let's get back to our interview with James Hetfield, Metallica's lead

singer and guitarist. Our interview was recorded in 2004 after the DVD

release of the documentary "Some Kind of Monster. It chronicled a difficult

period in the band's life. Everyone was so angry with each other, the band

hired a therapist who usually worked with sports teams to help them figure out

what to do. In this scene from the documentary, the band is listening back to

one of their rehearsal tapes. Hetfield doesn't like what the drummer at large

Ulrich is playing. Ulrich isn't very enthusiastic about the guitar-playing.

It hasn't been a good day.

(Soundbite of "Some Kind of Monster")

(Soundbite of music)

Unidentified Band Member #1: This is real confusing sounding.

Unidentified Band Member #2: It's just jacking the vocals all up. I mean,

it's clever and everything but, I mean, I don't see what it does to this.

Band Member #1: I think that's how you hear it, dude. And that's fine. I'm

just trying to do something different.

Unidentified Band Member #3: I mean, I'm used to having the drummer do the

beat part, you know what I mean, holding it together.

Band Member #1: Um. What I'm hearing is--let me choose my words carefully

here--um, it's pretty straightforward...(censored)...you know, it's, you know,

a little stock, so I started trying to introduce some kind of edge to it on

the drum.

Band Member #3: Those things we throw out to each other are complete

bull...(censored)... you know? It sounds too stock, it sounds too normal to

me. I mean, you know what I mean? You're saying it's...(censored)...so you

can get your point across about doing a drum beat. I mean, you know, it

doesn't hold any water.

Band Member #1: To you.

Band Member #3: It doesn't.

Band Member #1: I think it's...(censored)...stock. What part of that is

unclear to you? I think it sounds stock to my ears. I mean, you want me to

write it down?

Unidentified Band Member #4: If we have at least write it down...

Band Member #3: I think it feels stock, OK?

Band Member #1: I can hear you.

Band Member #2: ...so I...

Band Member #3: Carl, when you say--when you're telling me what to play right

now. You're telling me, you should play with what Curt's doing and I'm

telling you it's stock.

Band Member #4: Dude, fine.

Band Member #1: You know what, guys? Why don't we just go in there and

hammer it out, all right, instead of hammering on each other?

Band Member #2: This is so silly. You're just sitting there in a real pissy

mood and you're just sitting here being a complete...(censored)...

Band Member #3: You're really helping matters. You're really good at that.

I was straight up with you and I told you. I'm in a ...(censored)...mood and

what have you been doing? Picking at me all night.

Band Member #1: Come on guys. We have better things to do, all right?

Band Member #2: I do. I do.

(Soundbite of slamming door)

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: So there's this moment in the documentary when you were really angry.

You walk out...

Mr. HETFIELD: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...and then you go into rehab and you don't come back for 11 months

later. When you walked out of the room, did you know that you were headed to

rehab after that?

Mr. HETFIELD: Yeah. Yeah. It's somewhat deceiving in the movie that, you

know, I slammed that door, you know, Bob came out and we had a talk. You

know, eventually I came back another time and I talked about how things

weren't going well at home, how I'd got thrown out of the house, and a lot of

that revolved around that, and how things in the band weren't going well, or

at home, and just well what a--how lost I felt. My whole world was shaking

under me. You know, all of the roots, the foundations that I felt I had in my

life. And I came back and I talked to them, that, `Hey, I've--you know, after

so-and-so date I have to go away, I have to work on myself.'

GROSS: Right.

Mr. HETFIELD: And they knew. I couldn't just leave, you know. That was not

right. But it was disgust...

GROSS: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Mr. HETFIELD: ...and I told them, you know, `I don't know how long it's

gonna be, and I don't know. You're gonna have to trust me on this. I just

know I have to go and just, you know, I have to rebuild my life. I have to

strip down.' I had no idea what was in store for me really, but I knew I had

to get some help.

GROSS: Were you, like, a star in the rehab unit?

Mr. HETFIELD: That was the hugest fear out of everything.

GROSS: What, that you'd be or that you'd not be?

Mr. HETFIELD: That I would be.

GROSS: Mm-hm.

Mr. HETFIELD: That--and it's so silly now to think about it, but at that

time, you know, for me the biggest fear was--you know I had tried therapy

before and--to stop drinking and my just destructive behaviors, and I wasn't

really ready for it. And I thought, `Well, it doesn't really work for me.'

And then check--you know, my wife says, `You've got to check yourself in

somewhere. You've got to go to a hospital or a rehab or something.' It's

like, `No way. Don't you know who I am?' kind of thing, you know. `I

wouldn't get real treatment there, you know.' I couldn't do that. And my fear

was that I couldn't. There was no help for me and I was, of course, creating

that fear for myself to continue my behavior, you know.

But when I went there, I checked in under a different name, did all that

stuff...

GROSS: Ah.

Mr. Hetfield: ...you know, had the tag on that said, `Hi, my name is Frank

blah blah,' whatever it was. And at the first meeting they had in there,

people went around the room saying their names and what, you know, was going

on in their lives, and I just said, `You know what? My name is James and I've

got a fake tag on and this is crap and I'm here to get some help and I'm

fearful of this and this and this.' And I broke down crying and I told people

my fears and, man, they were just right behind me saying, `Don't worry about

it, you know, you're human. We're all humans in here struggling.' And that

right then, I knew I was in the right place.

GROSS: My guest is James Hetfield of Metallica. We'll talk more after a

break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Let's get back to our interview with James Hetfield, Metallica's lead

singer and guitarist. It was recorded in 2004 after the DVD release of the

documentary "Some Kind of Monster," which chronicled the period when Metallica

hired a therapist to work out problems in the band.

Whose idea in the band was it to actually hire a therapist and have the band

work through its issues like a couple might go to a marriage counselor?

Mr. HETFIELD: It pretty much is a marriage counselor. Old Mr. Towle, he

was a therapist. He didn't have a therapist license. He was an enhancement

coach, which was, you know, another form of, you know, attitude adjustment,

you know.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. HETFIELD: But basically, that told us that he could give feedback, you

know, and eventually it was tough to kind of just find the boundary of friend

and, you know, whatever, hired coach.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. HETFIELD: But he came on board when our management, Q-Prime, called and

said, `What do you think about this?' you know? `He's worked with another one

of our acts, and we got to get talking, you know.' Because that was the big

deal. There was no communication, you know. Over the years of this machine

of Metallica rolling on, we discovered that, say, a band like a Guns N' Roses,

they're in each other's face, they're very vocal about their attitudes, their

thinking, their feelings. We said, `We can't do that, you know, look at

them,' and they eventually break up, so we're not going to do that, so we shut

up for years and years and years, and that was self-destructive as well.

We had to communicate, so we got this guy, Phil Towle, to come in. He was

like a mediator in a way. He kind of made the room safe, neutralized the

room, so helped us talk to each other, because there was a lot of defusing of

bombs in the early days, so much baggage, tons--heavy stuff from years and

years of resentment that has just--had just crushed our creativity and our

friendships.

GROSS: Was there something that the therapist actually helped you understand

about the relationship of the members of the band that you don't think would

have emerged without him?

Mr. HETFIELD: Mm-hmm. Yeah. Well, when he brought up the word "ego," I

looked at Lars. He looked at me, you know. And then we had to look at each

other, ourselves, you know.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. HETFIELD: We had to look in the mirror. Like, `OK, yeah, all right.

I'll own a little bit of that.' And eventually, it's, like, yeah, you know

what? We're both--we've both driven each other to certain just egotistical

giants, you know. And thank God, Kirk, you know, was such the referee through

life, you know. And Jason obviously didn't fit in, because he was--he had--he

was, like, the minor ego, you know, and it was out of balance, you know, it

seemed like.

But yeah, that was a shock, somewhat. And yeah, you know, I brought up the

words, you know, "ogre" or "intimidator," you know, and how I hated being that

person. `I want to have friends. Why don't I have friends?' And they're

telling me, `Well, you're like this.' It's, like, `Well, no I'm not. I don't

want to be that. How do I not be that?' That's when I realized that that was

a tool I'd brought with me since childhood, you know. Intimida--man, my dad

was pretty darn good at that. He'd just shoot a look, and that was all.

That's all you needed to know. And, you know, it was such a great tool to not

have to get to know people, you know. I didn't have to get friendly with

anyone. Intimacy was so scary. And it still is, you know, to get so close to

someone. What if they leave? I would be crushed, you know. It's like the

amount of love that you give, to me, equated the amount of hurt when they

left, you know.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. HETFIELD: And it's still--I still struggle with that.

GROSS: You know what I find interesting, like the kind of fan who relates to,

like, the persona that you created, like the mythic version of yourself, the

on-stage version of yourself...

Mr. HETFIELD: Mm. Mm.

GROSS: ...and they're trying to model themselves on somebody who you're not

even.

Mr. HETFIELD: That's right.

GROSS: Do you know what I mean? It's like, this is something that you

created, it works really well when you're on stage, but it's not what you are

off stage, and they're trying to be that on-stage person.

Mr. HETFIELD: Yeah. It is quite a strange cycle and, you know, for me,

there are parts of me on the stage that are certainly me. You know, there's

somewhat of a hat or jacket that you put on...

GROSS: Right. Yeah, yeah.

Mr. HETFIELD: ...to go up and perform. We're performers.

GROSS: Yeah, yeah.

Mr. HETFIELD: But with a real heart and, you know, it's all really about the

music. But when fans come to see you play, they want to see something. You

can't just stand there and play. You could, but it's not as entertaining as

running around or showing on your face some of the anger of a song or some of

the sadness in a song or some of the thing--it is performing.

And then when they meet you at the airport, you're waiting for your bags and,

you know, they come up to you, `Hi, how's it going?' and you're, you know,

kind of tired from a flight and you're shaking hands and they're like, `Wow,

you're not what I thought you were.' And instantly, like, `Why do I feel

depressed about that, you know? So you think I should jump on the turn-wheel

and, like, smash some bags or what should I do, you know?' And I'm not going

to do that, you know? You know, yeah, this is me and maybe I'm in a crabby

mood, so go away, or, you know, whatever it may be. Or, hey I'm in a great

mood, come over here, let's take a picture and, you know, it's subjective to

moods at times. But when people get disappointed for meeting you, that's so

strange.

But I've owned what part is mine and what is theirs because, you know, they've

got something built up in their head that they need for their life...

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. HETFIELD: ...and if it's not that that they meet, they're disappointed

in what they've built up for themselves. And sometimes that's a tough reality

check. And, you know, so I leave that with them, but I also am nice and say,

`Hey, you know, this is another part of me.'

GROSS: James Hetfield, thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. HETFIELD: Thank you, Terry.

GROSS: James Hetfield is Metallica's lead singer and guitarist.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Our hard rock and heavy metal series continues through Labor Day, when

we'll hear from Alice Cooper. Friday's lineup will include stars of Spinal

Tap.

You can download podcasts of our show by going to our Web site,

freshair.npr.org.

I'm Terry Gross.

(Soundbite of music)

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.