Contributor

Related Topic

Other segments from the episode on May 31, 2018

Transcript

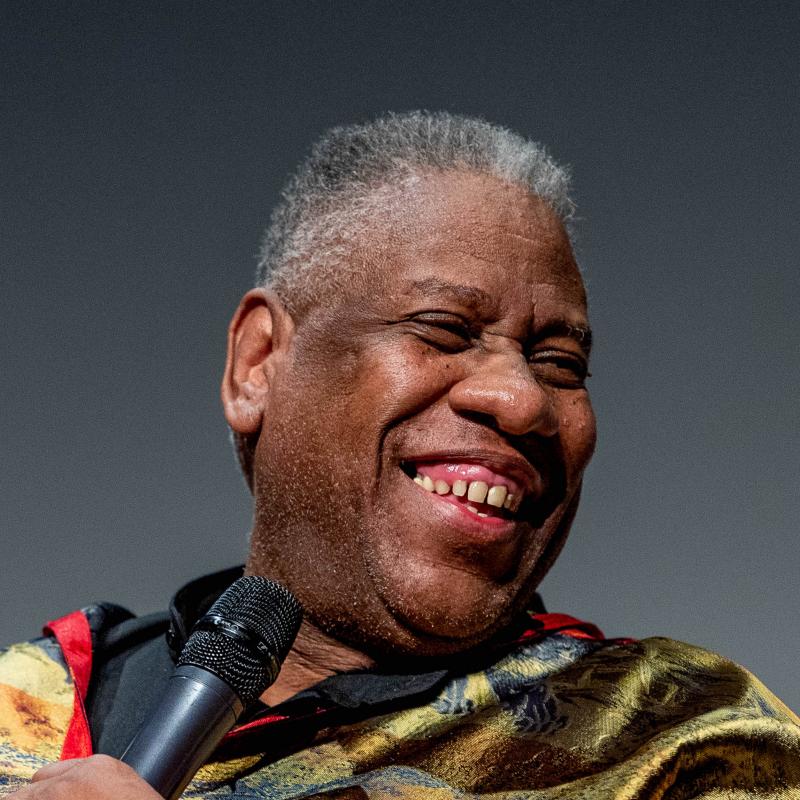

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR I'm Terry Gross. My guest, Andre Leon Talley, is famous in the fashion world and beyond. He spent much of his career at Vogue magazine, becoming the fashion news director in 1983 and creative director in 1988. From '98 to 2013, he was editor at large. He's a large man who covers himself in and capes and caftans made for him by some of the world's top designers. He has an outsized personality, too. Now in his mid-60s, he looks back on his life in the new documentary "The Gospel According To Andre." He grew up in Durham, N.C., in the Jim Crow era. His grandmother, who raised him, was a maid for the men's dorms at Duke University.

The fashions he was exposed to as a child came largely from what people wore to church on Sundays until he discovered Vogue magazine. Reading Vogue was considered a most unusual preoccupation for a 9-year-old boy. After getting a scholarship to Brown University and a master's degree in French literature, he moved to New York, worked at Andy Warhol's magazine Interview and was mentored by former Vogue editor Diana Vreeland when she was a consultant to the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Andre Leon Talley, welcome to FRESH AIR. Let's start with, how were you introduced to the world of fashion?

ANDRE LEON TALLEY: Well, from an early age, I discovered fashion through the pages of Vogue. I went to the public library in Durham, N.C. And I was about 10 years old or maybe 9. And I discovered this magazine called Vogue. And in those days, it came out on the 1 and the 15 of every month. And the editor was Diana Vreeland. And this was my escape world. When I was a young boy, I grew up in my grandmother's home in Durham, N.C., a modest home. She was a maid at Duke University. And it was just my grandmother and myself. She was an extraordinary woman. She was a frugal woman. And she watched her budget. She had a bank account. And we had a wonderful life because I never knew anything but love, unconditional love.

GROSS: So you're a 9-year-old boy, and you're totally fascinated by these fashions that adult women are wearing. So what captivated you as a 9-year-old boy about the world of Vogue?

TALLEY: The world of Vogue meant more to me than what the women were wearing as models. The issues of Vogue captivated me not only before the images of the fashion spreads, but it was the magazine itself that turned me on to a world that I did not know, had not been exposed to. It was a world of literature, what was happening in the world of art, what was happening in the world of detainment. It was my gateway to the world outside of Durham, N.C. It wasn't just the fashions. Of course, I loved the fashions. I loved the beautiful images. And I related so much to the images and then the written words, the captions, the articles.

So I was living through Vogue as an escape hatch but reading every single page, loving every single detail. I mean, they had a men's column called Men In Vogue, and that was very fascinating to me. Then Maxime de la Falaise had a cooking column. That was fascinating to me. And then, of course, the main spreads, they were all orchestrated by the great editor Diana Vreeland. And they were basically built on her fantasy, but she just gave me the world. I discovered Truman Capote. I discovered the great ballerinas from the Bolshoi who defected to the West. I discovered Nureyev and Avedon photos. Nureyev's was nude, photographed by Richard Avedon. All of this was just very exciting to me. And it was a world that I internalized and I kept to myself as a young man because nobody was interested in Vogue or fashion other than I. And I was ripping pages out of Vogue, putting the pictures up on my wall in my room with thumbtacks. And I just had a room wallpapered from head to ceiling, floor to ceiling with images from Vogue.

GROSS: So just to set the scene, while you're entering the world of Vogue and very much wanting to live in that world of fashion and literature and music and art, yeah, so describe the actual house you were living in.

TALLEY: My grandmother's house was very modest. It was a house of four rooms - a kitchen, living room, two bedrooms and one bath. And we did not have central heating. I remember we had cold heating when I was very young, and then we converted to gas heating. We had a gas stove in the front bedroom where I slept. And then we had a gas stove in the kitchen which heated up my grandma's bedroom. But this house was a house of immaculate cleanliness. My grandmother was a great, great housekeeper. She gave me the chores of scrubbing the front porch, scrubbing the floors. I had to scrub the floors once a week. I learned to scrub the floors. I also learned to polish the woodwork in the living room with Johnson's paste wax. That was hard - to get the floor to shine.

And I did this as a young man. And all the time my grandmother was going to work to be a maid. She'd come home at 3 o'clock every afternoon, make supper. We sit down and look at the wonderful TV we had. My father bought the TV for me from Washington, D.C. We had a black-and-white television. And we - I remember in the house, the stove was a very great memory for me in the kitchen because the smells from the kitchen were wonderful. I remember my grandmother making wonderful lemon pound cakes and the smell of vanilla extract - McCormick's vanilla extract.

GROSS: Oh, the - yes (laughter).

TALLEY: The color of the vanilla extract and the smell was amazing, still lingers in my memory.

GROSS: So were you bullied when you were in high school?

TALLEY: Of course I was bullied. I was bullied and beaten up and everything.

GROSS: What was your defense?

TALLEY: I would get on the school bus, and I would say something. And they would just pounce on me because also I had beautiful clothes. I didn't have a lot of clothes. But my grandmother and my father would put me in the best clothes they could afford. And I had beautiful sweaters and trousers and beautiful penny loafers and quality shoes. And I didn't show off. I wasn't a show-off. I wasn't showing off. But I was just getting on the school bus. And I was tall and skinny, and they just would beat me up (laughter).

GROSS: So was there a way you could defend yourself?

TALLEY: I only defended myself through silence and not being a disrupter. I didn't fight back. I didn't know how to fight back. And I didn't know how to articulate this to my grandmother or anyone. The boys were very nasty to me. I remember once I built a snowman. School was out because of the snow. And there was a beautiful snowman in my yard. And this Reginald Hinton (ph) - he's dead now - he came into the yard and destroyed the snowman once it was completely built. You know, he just crushed it.

Another time, my friends - they were cranky and naughty - Bruce (ph), my best friend, built a ditch and covered the ditch over with grass. And I had to my best cowboy outfit I had gotten for Christmas. I had a very beautiful cowboy outfit my grandmother got me for me. And I put it on, and I was running around in someone's backyard. And Bruce - I was supposed to chase Bruce. And Bruce ran in the direction of this covered ditch. And I fell in the ditch, and I tore a hole in the trousers of my cowboy outfit, and I never put it on again. But then Bruce became my best friend. I think Bruce was the only man - the only young guy that was really a close friend. He really - and my father liked Bruce, and I liked Bruce. And he's in the documentary.

GROSS: OK. Wow. So I want to kind of collapse a period of your life here. So you move...

TALLEY: Collapse it, darling.

GROSS: So after you graduate high school, you go to college. And you move to Rhode Island to go to Brown University for your masters, your undergraduate and master's degree both in French literature.

TALLEY: I got my undergraduate degree in French literature. And I tell you, when I went to Brown and won that scholarship, the world opened. When I got on the train - I went to Brown on a train from Durham, Raleigh-Durham. I took the train. My uncle went with me. He rode with me to Philadelphia. I had all these boxes on the train. I had huge boxes and things I was taking to Brown. It was the first time ever being away from home. So I went to Brown alone. I went to the campus alone. I navigated my way alone.

And I got to Brown, and the world opened up - the world of exposure, the world of literature I discovered even more. The great, great poets - Baudelaire, Rimbaud. I discovered the beautiful paintings of Eugene Dell'Acqua. I discovered Manet. I discovered the great world of art, things - music. Music had not been - classical music not been a part of my upbringing. Gospel music and church music. And in the world of Brown, I discovered beautiful classical music, piano music, Chopin, Clara Schumann. Things like this were really new to me. And I was so curious about everything. And the people were so sophisticated at Brown and at RISD, the Rhode Island School of Design. So I just had the world opened up to me in just ways that had never been opened to me before.

GROSS: You know what? I realized you are one of the few guests I've had who talks even faster than I do.

(LAUGHTER)

TALLEY: I'm talking fast, but I'm loving it. I hope that you understand it.

GROSS: I absolutely understand, and I'm quite enjoying it (laughter).

TALLEY: OK.

GROSS: Let's take a short break here and then we'll talk some more. If you're just joining us, my guest is Andre Leon Talley, who for a long time was the creative director at Vogue magazine. There's a new documentary about him which is called "The Gospel According To Andre." We'll be back after this break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MGMT SONG, "ELECTRIC FEEL")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR, and if you're just joining us, my guest is Andre Leon Talley, who's a kind of giant in the world of fashion magazines. He was for years the creative director of Vogue magazine. And now there's a new documentary about him called "The Gospel According To Andre." So you get to New York after graduating from Brown and you'd always wanted to meet Andy Warhol and the people who he helped make famous. And you not only got to meet them, you got to work at his magazine, Interview magazine...

TALLEY: Yes.

GROSS: ...Which I should say, parenthetically, just filed for bankruptcy...

TALLEY: And closed.

GROSS: ...And closed, yeah.

TALLEY: It folded.

GROSS: So when you were there and got to see all of the, like, Warhol superstars and everything, what made the biggest impression on you in terms of your own life, in terms of your own personal and professional identity? - because you were, you know, you were in your early 20s, I imagine, at the time. And it's a very formative period when you're still, you know, shaping who you are and figuring out who you want to be. And you're looking at all these people who kind of remade themselves, who transformed themselves into something else.

TALLEY: Well, this is what I loved. I loved it. I loved the world. Now, the people that I met through Warhol were the people that I always wanted to know. They were not bullies, they did not judge you. There was unconditional admiration, if not love. People were free, people had made their choices, people were different. You know, some people perhaps had better clothes than others. But everyone was noted for their own worth, their own gifts. And I think that's why I felt so good because I felt at home.

I felt that I was part of a special club at Andy Warhol's Interview magazine. And they embraced me, and there was no criticism of me as there would have been at home in Durham, N.C. You know, I was brought up in a very strict, modest home. But my nucleus - the nucleus of my family was church. So being a black man brought up in the African-American Missionary Baptist Church culture meant that I had certain rules and certain ways to deport myself through clothes and not only through my actions or attitudes about life.

But when I got to meet Andy Warhol and people were walking around in jeans and blazers and sometimes Rive Gauche and sometimes not Rive Gauche, the world came to the doors of the Factory and Andy Warhol. Interview was the gateway to the world for me.

GROSS: Well, another thing about the Andy Warhol crowd is that there was a lot of gender and sexual fluidity.

TALLEY: Gender and sexual fluidity but it wasn't rampant and it wasn't overt. People went into the office and there was a deportment about going into the Factory. You had a certain culture of the office and the Factory, which was very correct, very traditional, yet very relaxed and casual. There were all kinds of people. There were lesbians, there were gays, there were straights, there were drag queens, there were artists. But everyone was equal, so everyone mattered. And no matter who you were, it mattered.

You mattered because you had individual gifts and talents. And that's what Andy admired. Now, there wasn't a lot of sexuality going on. I did not see people having sex rampantly at work or taking drugs because it wasn't that atmosphere. When I got to the Factory, it was long after Andy had an assassination attempt. So the rules changed. So people were chosen for their seriousness and chosen for their possibilities to become who they wanted to be. And I was allowed to become who I wanted to be at the Factory and with Andy Warhol.

GROSS: Right. So eventually, you get to Vogue. You were a man at Vogue. You were also an African-American man at Vogue.

TALLEY: Yes, yes.

GROSS: So I'm sure you stood out. Did you feel like you were with your people or did you feel like you were separate?

TALLEY: I never felt bullied. I felt that I was on top of the world. I felt that I was with the best people. After all, Vreeland had endorsed me. I had the full endorsement. It was like if you had a political endorsement. It was the full endorsement of Vreeland and Andy Warhol, who were, for me, the king and queen of New York. The empress of fashion had endorsed me. I had proven to her - I had assignments and challenges she gave me for certain installations in her shows. And I had proven to her my worth. I never feared anything.

I never doubted myself once. I am a deeply insecure person for many reasons. I never showed my insecurity. I just rose to the occasion. I stood up straight and tall, like a tall, tall sunflower, and I just radiated the light and the beauty of my mind in relationship to the world of fashion.

GROSS: So at Vogue, you eventually became in 1988 creative director. What is the job of the creative director?

TALLEY: Well, that is a very gilded title. But, you know, it is gilt-edged hell, it's gold-plated hell, according to Tennessee Williams from "Sweet Bird Of Youth." You know, I knew the gilt-edged hell I was going to. The creative director is the person that's there to buttress the editor in chief. And it's sort of like a vice president, you know what I mean? A very high position but there's the president and the vice president and he's there or she is there to support the role and the policies and the vision of the editor in chief.

It's there to give assignments, there to give ideas, to create ideas for the fashion pages and come up with ideas for shoots, maybe not always received. But you just had to talk a lot. You had to talk a lot and be there all the time.

GROSS: What are some of the...

TALLEY: You had to go to lunch too with very important people.

GROSS: And what was the point of the lunch?

TALLEY: Bill Blass, Oscar de la Renta.

GROSS: What was the point of the lunch?

TALLEY: Lunch - you know, social networking with Bill Blass and Oscar de la Renta.

GROSS: Why was it important to social network with them? What did you need from them?

TALLEY: They were top designers in New York, and you had to have a relationship, establish that relationship at Vogue so that Harper's Bazaar wouldn't get that advertising.

GROSS: Oh, I see because they needed you. I mean, but you needed them for the advertising.

TALLEY: Yeah.

GROSS: But that leads to a question. In the fashion world, I'm often really confused in fashion magazines about where the line is between advertising and editorial.

TALLEY: Well, it's more blurred today than ever before. Now, we were working in fashion. They were not blurred. The advertising department was separate from the Vogue department. And this is why Vreeland was great because in her decade of being editor in chief, she never gave a whit about what the advertisers said. She invented what she wanted as a fashion spread. She invented the fashion spreads that were fabulous, cinematic, based on famous films. I remember when she did a whole spread of clothes by "Queen Christina," âGreta Garbo's great film, on Veruschka.

And there she had the designers like Oscar and Bill make costumes or evening clothes that were inspired by "Queen Christina." Now, that was a very, very definite line between the advertising and the editorial. Now the lines are blurred more and more because it's more and more difficult to get those pages secured on an annual basis. So it's less - it's more of a stratagem where the advertising has slowly ebbed its way into the fashion editorial department. And they lean heavily on making sure that you get the right credits. Sometimes, they say, well, we've got to have the dress in because they've taken out six pages of advertising for the September issue. Now, that happens in every magazine. That does happen everywhere.

GROSS: Wait. Let me stop you right there. So they've taken out six pages. And what are they asking you to put in the magazine in exchange for that?

TALLEY: Well, the advertising department come and say, well, please, you've got to put this particular designer in your editorial because - you remember. They've taken out six pages - whereas you might have five dresses from a man that didn't take out advertising. You might want to do five Alaia dresses because his dresses are so great. But then the role of the advertising department is to stay on the backs of the editorial department and to remind them - well, remember. You have the advertising of Bill Blass, and he's taken out six pages. And you've got six Alaia dresses you want to run on these pages. We've got to honor Bill Blass for his advertising commitment.

GROSS: So you have to do either a feature on Bill Blass or showcase his clothes?

TALLEY: Showcase his designs in an essay that you might have included six dresses by Alaia.

GROSS: Were you comfortable with that blurring of the line between advertising and editorial?

TALLEY: One is never comfortable with that blurring of the line. But one has to live up to the responsibilities and demands of the job. One is never comfortable. One - the luxury of true, true editorial is very rare in any fashion magazine. But one has to honor the commitment to create the dollar that pays your salary, that gives you food to eat.

GROSS: Is fashion different because the advertising and the content...

TALLEY: It is very different.

GROSS: It's all the same people - like, the people who you're writing about are the same people who are taking, like, the advertising.

TALLEY: No, the content is different because the advertising is more demanding. The advertising is bigger. So they can demand - I remember once Estee Lauder - the late Estee Lauder was very upset because the Vogue issue had come out at Christmas. And it said there were three great queens of the beauty empire. And they were Helena Rubinstein, Elizabeth Arden and Paloma Picasso. And Paloma Picasso at that time only had a lipstick, and it was called Mon Rouge - and maybe she had a scent. And Mrs. Lauder called up to the heads of Conde Nast and said, all of my advertising will be removed not only from Vogue but from all the other magazines because she was an empire - Estee Lauder was an empire. And that was revenue that was going to be yanked out of Conde Nast. And Anna Wintour set me straight down to Palm Beach, Fla., to do a major profile on Mrs. Lauder...

GROSS: Wow.

TALLEY: ...To make up for that slight.

GROSS: So I have to say that is not exactly emblematic of what journalistic ethics are supposed to be.

TALLEY: Well, I mean, it's not The New York Times, and it's not The Washington Post.

GROSS: No, exactly. Yeah, yeah.

TALLEY: It is fashion.

GROSS: But the thing is I think a lot of readers really can't tell the difference anyways between advertising and editorial because...

TALLEY: Well, you have to have an intelligent and sophisticated eye to tell the difference because it's more and more blurred. Most fashion magazines that are worth their metal usually are full of advertisers - advertising pages. And those pages are almost created like editorials anyway.

GROSS: Exactly, right.

TALLEY: So it really isn't making a difference whether you looking at the advertising page or the editorial page. Sometimes they blur all into one. Most of the great magazines do that nowadays.

GROSS: My guest is Andre Leon Talley, the former creative director of Vogue magazine. The new documentary about him is called "The Gospel According To Andre." After a break, we'll talk about how he dresses in capes and caftans. Also linguist Geoff Nunberg will talk about the controversy over whether schools should teach cursive handwriting. And film critic David Edelstein will review the new heist movie "American Animals." It's a blend of fiction and documentary. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF NINO ROTA'S "LE NOTTI DI CABIRIA")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Let's get back to my interview with Andre Leon Talley, who spent most of his career at Vogue magazine as fashion news director, creative director and editor-at-large. The new documentary "The Gospel According To Andre" looks back on his life and tells the story of how he made a place for himself in the international fashion world after growing up in Durham, N.C., in the Jim Crow era.

So one of your contributions in terms of personal style to fashion is your capes and your caftans. How did you start wearing them? And I should say these are not ordinary capes. These are, like, amazingly designed - like, sometimes out of fur.

TALLEY: (Laughter) Meticulated (ph), fur - and just thought out and processed with the great class - world-class designers. Well, when I went to Marrakech and saw that the men in North Africa - in Marrakech, in Casablanca - walked around in caftan shirts and loose-fitting clothes all day, every day. They woke up. They put on their long-sleeved, to the floor - ankle - shirts to the floor. They had caftans. And this is the indigenous dress of the black man in Marrakech. And this is - I decided I wanted - we like that. I want to wear that instead of a suit because it's comfortable. You're ventilated. You're roomy. You're cozy. And you can just stretch. And I'm not a tall stick anymore. I'm a big, big guy of great girth. And people think I look like - maybe my clothes don't look that important, but I have taken great time and fittings for my capes and caftans made by the great designers. So I will continue to wear these things through the rest of my life.

GROSS: Did your weight have anything to do with wanting to wear capes...

TALLEY: Absolutely.

GROSS: (Laughter).

TALLEY: Absolutely. My weight issue is an ongoing thing. It's an ongoing battle. I've battled it. I've battled the bulge of the biscuits - 540 calories - at the Duke Diet and Fitness Center. I go there often, almost every other year. It's a place where I go, and it's disciplined. But I've had weight issues. And, of course, my weight issues obviously go back to my childhood and the loss of love. And I considered - I associate food with love from my grandmother's home, the modest home and the kitchen.

My grandmother used to make me a pan of biscuits every Sunday morning, just for myself. And you don't know how wonderful that smell is of those hot biscuits with butter and molasses. I have carried that throughout my life. She would make lemon poundcakes. At Christmas, we had fruitcakes, chocolate cake, coconut cake, lemon poundcake. Four or five cakes, six pies sitting, waiting to be eaten on Christmas Day for the family. And so this...

GROSS: But you were skinny as a young man. So something changed.

TALLEY: Something changed when my grandmother died. When my grandmother died, I started eating fuller. And I just don't know how to discipline. I'm sorry. Everyone in America is perhaps overweight. And I totally empathize with people. I feel very bad. But I did select caftans at a certain age. And my suits - my beautiful custom-made suits are put away because the caftans create a stately, tall image. You can look great in them and look slim.

GROSS: So one of the things you mention in the new documentary about you is that you've never had a long-term romantic partner and that you were, you know, very preoccupied with your profession and loved your profession very much. Have you reflected a lot on why you think you never went in that direction?

TALLEY: Every day, I reflect upon that.

GROSS: Yeah.

TALLEY: Well, as Diane von Furstenberg, who's a dear friend of mine, said, I was afraid to fall in love. I was afraid of the rejection. I was afraid of the emotional commitment. And I was not deliberately making the - navigating through the shores and chiffon trenches of my career. It just wasn't a part of me because - although I lived in a world of great promiscuity and libertine ways in the '70s - Studio 54, Paris. And I discovered the freedom of people embracing people for their individuality or - not just their sexuality - that you could be gay. You could be quattro-sexual (ph) or pansexual, as Janelle Monae says. I just loved living the life that I lived, living through the world that I was exposed to on the front row from fashion and bonding with people that I could have conversations with.

As you remember, I was living the life of an only child in a home with my grandmother. So we didn't have many conversations. I didn't have much to say to my grandmother - except that she only read The Missionary Helper, her Bible, and the newspapers. And she did have a cookbook. She never cooked from a recipe written. All her recipes were in her head or borrowed from her sisters verbally on the telephone. She grew the most beautiful geraniums. She had rows and rows of clay pots with geraniums every year on the porch, roses in her rose garden. Everything was done by instinct or rote.

So I didn't have much to say to my grandmother. And I was very quiet, and so I didn't have people to talk to. I was very much alone in my childhood except for Vogue. And Vogue was a world. It was like "Alice In Wonderland" almost. I had just gone down the rabbit hole of this world of glamour through the pages of writing - the spoken, written word. The word mattered as much as image.

GROSS: How does that relate to not having a partner?

TALLEY: Well, I didn't have time. As Diane said, you are afraid of relationships. I was emotionally afraid of people, so I did not want to get close to people. I do not want people to touch me. I didn't like to touch people. So that is just a part of who I am. And I regret to this day. I have difficulty responding to physical emotion. And it's based on, I guess, a childhood experience. I don't know what it is. I can't relate to that - or I can't think about that now. But I do regret not having that relationship. I regret not having siblings.

And I think about it almost every day because, as I get older, it's very, very lonely. I have to live a lonely life. I live in my own guilt gold-plated hell. As Tennessee Williams says, I know the gold-plated hell I'm going to. And I invented this gold-plated hell. And now I must live in it. I have a beautiful home. I have beautiful books. I have beautiful furniture, beautiful art, beautiful music. I love movies. I have beautiful clothes. But I live in a gold-plated hell. However, I'm not going to say it's the worst life. It's been a wonderful life.

GROSS: You know, you're talking about how you were quiet when you were growing up and alone. And you're so gregarious and so talkative and so easy to talk to. It seems like two different Andre Leon Talleys.

TALLEY: There is two different Andre Leon Talleys, as I said. Of course, there are two different Andre Leon Talleys because you - I have someone to talk to and listen to what I have to say. And I didn't have that when I was growing up. I was very much a silent person. I was afraid of people. I went through high school thinking no one liked me. Then I realized people really adored me in high school. I mean, I have great friends who have come to me recently - a friend who I had lost contact with, and I recently found out where he lived. And his name is Barry Parker (ph). He lives in Durham, N.C. And I thought - I just didn't think he liked me in high school. I considered him a friend. But then I contacted him, and he considers me a close friend. And we are very close now. It's just amazing how I went through high school thinking I was an outsider. And I didn't discuss that with anyone. I had no one to discuss it with at home except for, you know...

GROSS: Well, people were beating you up also, so you had every reason to think you were an outsider.

TALLEY: Yeah, yeah. I was an outsider. I was an outsider with class and style. And I knew that I had style. I knew that I had style. I knew that I had style based on something very strong. I remember. I would see Ed Sullivan and the great talents he would have - like Tina Turner, Ike Turner, James Brown. Those people impacted upon me. Ike Turner had a big belt, and I wanted a belt just like that. I remember. He was on the cover of "Ebony" magazine in 1971 - May. And he had this big belt and a red sweater with no sleeves and plaid trousers tucked in the boots. And I wanted to look like Ike Turner. I didn't want to be like Ike Turner - beating up Tina Turner. But I wanted to have that look.

GROSS: I hope.

TALLEY: And those looks I aspired to. I wanted to look like a pirate. And I dressed like a pirate.

GROSS: So you talked about how you were afraid to be touched. You didn't really want to be touched. I'm wondering if the AIDS epidemic had anything to do in reinforcing that feeling.

TALLEY: No, it did not. Well, the AIDS epidemic did not - I was not afraid of people with AIDS. But I was very aware of AIDS. And I was very aware that AIDS could take you out, and you had to be careful. When AIDS started, people were getting sick with sarcoma - Kaposi sarcoma - is that correct?

GROSS: Kaposi sarcoma.

TALLEY: And it was very - mystery. It was very new to us. And I was reading everything I could about it. And people were dying and going away. And I thought, this is very, very heavy. So this is another moment to pull back from people. And I never really, really, really got involved with the people ever, ever. I had great emotional experiences, contacts with very strong, strong people. These people are wonderful. I've had more emotional and physical contacts with women than with men. And I will not name the women, but they have been famous women. So there you are. That's all you need to know, Terry.

GROSS: OK. That's good enough for me.

TALLEY: We're not talking about that anymore (laughter).

GROSS: Oh, that's good enough for me. OK. So during the course of this interview, you've mentioned your father and your grandmother. I don't think you've mentioned your mother.

TALLEY: Well, my mother, she was a part of my life. And my father and mother divorced when I was 9 years old. And my mother was very much in my life. Her name was Alma Ruth Talley. And she died in 2015, I think - 2014, 2015. She's buried in a cemetery and beautifully - the ornaments - the grave markers, I've spent a great deal of time designing it, and it cost a lot of money. And her funeral service was one of the most beautiful services ever at Mount Stanier (ph) Baptist. And I spent a lot of time designing it. I spent a great deal of time. And Dr. Butts flew in and gave the eulogy for her funeral.

GROSS: Calvin Butts?

TALLEY: Calvin O. Butts III. I flew him in, and he gave the eulogy. And so I do respect my mother. And I had a relationship with my mother. But I'll just tell you why you haven't spoken so much about my mother. When I was at Brown - this is just to give you a story and we're going to stop. I'm not going to say any more. I was at Brown, and I came home for Christmas. And I was wearing a ankle-length navy blue naval officers coat with gold braid on the cuffs that I'd bought at a thrift shop. It was a maxi coat. That was the equivalent of a maxi coat. But it was to the floor with gold buttons - gilt buttons, naval coat. It did cost a lot of money, but it was - had a great deal of style. And it was very heavy. It was very warm.

My mother and I got out of the car, and you had to walk up to the - walk to the church. It was about maybe a hundred feet. And my grandmother had gone to church before us. She was very sprightly. And so my mother looked around at me and she said, well, you have to wait and walk behind me. I can't walk in church with you. I said, why, what's wrong? She said, well, I can't be seen with you with that "Phantom Of The Opera" look. And I said, OK, well, I'll just hold back. And you can go on in the church. And I'll just come behind you. So this - I was maybe 24 and I realize, this is my mother, and I must respect her. But this is the mother who does not get me. And thank God for my grandmother.

GROSS: When your grandmother died in 1989, did she have a clue how successful you'd become?

TALLEY: Oh, she was very proud of me. She was very - indeed very proud, very proud. She had a great clue. She knew. She spoke to Mrs. Vreeland. She knew I was on the top of the world at Vogue. She was very proud.

GROSS: Did you dress her at all?

TALLEY: Oh, of course I did.

GROSS: (Laughter) What were the grandmother clothes for her?

TALLEY: Well, good grandmother clothes were not necessarily clothes. They were accessories. And in the summer, I would go to Garfunkel's (ph) when I was a park ranger in the government - a park ranger at the Lincoln Memorial and a park ranger at Fort Washington. And I would go spend all my money on gloves - leather gloves for my grandmother to wear at church, black leather gloves. And I'd buy her beautiful Koret handbags - K-O-R-E-T. These are all the bags and things I discovered at Vogue. And then I would buy her sometimes shoes. But I was not big on shoes because I bought a pair of the very expensive alligator shoes once on a very high heel, a thick high heel, and I remember she did not wear them much. And she didn't want to hurt my feelings. She just didn't wear them much. And I realized that I made a bad choice because the heels were too high.

But she loved all the things that I bought. I bought beautiful hats. And Karl Lagerfeld used to give me beautiful fabric from his collections at Chloe. And I would take the fabric home, and she'd have beautiful dresses made. And those dresses are still in her closet. And then finally when I got to be big at Vogue, I would buy Chanel suits from the ready-to-wear and give them to my grandmother to wear to church. And she loved them. And she was very proud of - a navy blue suit and a pink suit.

GROSS: All right. It's been a pleasure to talk with you. Thank you so much.

TALLEY: Well, Terry, it's been a great pleasure talking with you. Thank you so much.

GROSS: Andre Leon Talley is the subject of the new documentary "The Gospel According To Andre." After a break, our linguist Geoff Nunberg will consider the controversy over whether schools should teach cursive writing. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF LARY BARILLEAU AND THE LATIN JAZZ COLLECTIVE'S "CARMEN'S MAMBO")

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. In recent years, educators and legislators have been confronted by a national movement aimed at restoring the teaching of cursive handwriting in the schools. But to our linguist Geoff Nunberg, in an age when people rarely communicate with each other in longhand, that doesn't make much sense.

GEOFF NUNBERG, BYLINE: Is longhand doomed? People were predicting that as early as 1938, when The New York Times warned that writing by hand would soon be swallowed by the universal typewriter. Eight years later, people are saying that it will soon be supplanted by the typewriter's souped-up digital offspring, yet handwriting's on a tear right now. Five or six years ago, I'd walk into my Berkeley classroom and see rows of undergraduates peering over the lids of their laptops. Now most of them are writing in notebooks.

My co-teacher and I don't impose a no-devices rule like some do, but we don't have to. The students have learned that they'll remember more of a lecture if they take notes in longhand than if they use a laptop, and the research confirms that. That's not just because they're spared the temptation to keep checking Facebook. Handwriting has the virtue of being slower than typing on a keyboard. You can't just switch on autopilot and take down every word. You have to actively process and summarize what you hear.

There was never any real danger that digital technology would replace pen and paper no more than it would kill the printed book. Yet we really have come to the end of an era even so. The writing styles we use trace their ancestry back to ancient Rome, but until recent times, they were always meant to be read by others in manuscripts, letters, ledgers and reports. But once our graduating seniors hand in the blue books for their last final exams, they'll probably never again have to produce a piece of extended longhand to show to anybody else. They may use it to keep a personal journal or to write the first draft of a novel, as a lot of authors still do. But their longhand communications will be mostly limited to filling out a form at the DMV or leaving a note under somebody's windshield wiper.

Several of my students write in cursive, others use some form of print. One writes in all-caps, another in a rather elegant modern italic. But as long as their writing's legible, why should I or anybody care which style they use? Yet handwriting has become hugely political in recent years with the rise of a movement that sees the neglect of cursive as a symptom of cultural decline. The creators of the Common Core didn't include cursive instruction because a lot of teachers thought it took too much time away from other things. But state legislatures in Alabama, California and other states have mandated it. In Louisiana, the drills continue all the way up to Grade 12. And where schools aren't teaching it. there's a booming business in cursive summer camps.

There's no sound reason for any of this. It's been shown that learning to write by hand has cognitive benefits, but it makes no difference whether you connect the letters or not. Cursive doesn't make a signature more legal. And though many may find this hard to believe, cursive actually turns out to be slower than print, although the fastest style is a hybrid of the two. But cursive is steeped in tradition. It evokes an age when American schoolchildren sat at their desks in identical postures, making their loops with military precision. The drills trained them to join the growing legions of clerical workers, pen pushers as they were called at the time. But they were also thought to build character.

As the historian Tamara Thornton puts it in her book "Handwriting In America," cursive instruction was intended to reform the dangerous, discipline the unruly and accustom the dissatisfied to their role in life. Some people still talk about cursive instruction as instilling self-discipline, but the only jobs that require fastidious penmanship these days are as a tattoo artist or addressing wedding invitations. So modern advocates of cursive emphasize being able to read it, rather than write it. And kids certainly do need to be able to decipher the letters they get from grandma. But experts say that once 6-year-olds can read print, they can learn to read ordinary cursive in an hour without years of drills. Some conservatives say that neglecting cursive leaves students sadly unable to read our founding documents like the original Declaration of Independence, the Mayflower Compact or the Magna Carta. But it's not likely any of those people have actually tried to do that themselves in as much as the first of those documents is illegible, the second isn't written in cursive, and the third isn't even in English.

I can understand the prejudice against print. When I was growing up, I thought of it as a childish form of writing that you abandoned when you started to learn grownup cursive. But print styles go back to the Renaissance. And over the years, a lot of authors have chosen to use print over cursive, from Charlotte Bronte and J. R. R. Tolkien to Jack Kerouac and David Foster Wallace. In an age when most of our handwriting is just for our own eyes, why would we insist that everybody write the same way? You may as well dictate what song we all have to sing in the shower. Let the schools teach cursive, by all means, but as Anne Trubek, the author of "The History And Uncertain Future Of Handwriting" suggests, it should be an elective like signing up for band. There are so many nice ways to write, why not give students a free hand in the matter?

GROSS: Geoff Nunberg is a linguist at the University of California Berkeley School of Information. After we take a short break, our film critic David Edelstein will review the new movie "American Animals," a blend of fiction and documentary. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF CLAP YOUR HANDS SAY YEAH'S "OVER AND OVER AGAIN (LOST AND FOUND)")

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. On December 17, 2004, four young men stole books and manuscripts valued at more than three quarters of a million dollars from a Kentucky college library's rare book collection. Their heist is dramatized in Bart Layton's new film "American Animals." It's a blend of fiction and documentary, using actors and onscreen interviews with the story's actual participants. Film critic David Edelstein has this review.

DAVID EDELSTEIN, BYLINE: The heist movie "American Animals" opens with a cutesy title. This is not based on a true story. Then the words not based on disappear, leaving - this is a true story. I doubt any fiction writer could have dreamed up a heist so dumb, stealing the original of Audubon's multivolume "Birds Of America" from the library of Transylvania University in Lexington, Ky. The movie is funny in spots, but it's not a comedy. The British writer-director Bart Layton has set out to explore the cultural underpinnings of a particular American brand - a birdbrain. The heist was executed in 2004 by four middle class suburban college students and grads - young men, we're told in on-screen interviews with their real parents, who'd never been in trouble with the law.

The likeably raw, young Irish actor Barry Keoghan plays Spencer Reinhard, who actually has artistic talent, and on a library tour is mesmerized by Audubon's book. But it's Warren Lipka, played by Evan Peters, who decides that they and two others should disguise themselves as elderly scholars, taze the librarian, snatch "Birds Of America" plus a first edition of Darwin's "On The Origin Of Species" and find a buyer through a fence in Amsterdam. Why? That's something even the real four have trouble answering in interviews that pepper the movie between the fictionalized scenes in which their younger selves do stakeouts, make charts and watch such films as Kubrick's "The Killing" and "Reservoir Dogs," a DVD shelf of American robber archetypes. You can hear how movies saturate their lives when in a restaurant, Warren works his weird magic on another student, Eric Borsuk, played by Jared Abrahamson.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "AMERICAN ANIMALS")

EVAN PETERS: (As Warren Lipka) Hey.

JARED ABRAHAMSON: (As Eric Borsuk) What's up, man? What's with all the mystery?

PETERS: (As Warren Lipka) I'm here to talk to you about something deadly serious.

ABRAHAMSON: (As Eric Borsuk) I figured you must want something.

PETERS: (As Warren Lipka) Actually, I came to offer you something.

ABRAHAMSON: (As Eric Borsuk) Oh, really?

PETERS: (As Warren Lipka) Yeah.

ABRAHAMSON: (As Eric Borsuk) Yeah?

PETERS: (As Warren Lipka) There's no one else I could trust with this. You're either in or you're out, right now.

ABRAHAMSON: (As Eric Borsuk) How can I tell you if I'm in or I'm out without you telling me the first thing about what I might be in or out of?

PETERS: (As Warren Lipka) I would just need you to say in principle - OK - because this might be something not exactly legal. And there's a chance that we would have to leave everything behind.

ABRAHAMSON: (As Eric Borsuk) OK. When you say not legal....

PETERS: (As Warren Lipka) I'm going to say this one time and one time only. You're either in or you're out. Right now.

ABRAHAMSON: (As Eric Borsuk) I'm going to need more than this one.

PETERS: (As Warren Lipka) Not until you commit. This would be something dangerous and very exciting that I need you to be a part of. This could change everything. This is your red pill or blue pill moment, my friend.

EDELSTEIN: Evan Peters' Warren is a magnetic sociopath, the linchpin of "American Animals." But he wouldn't sway Spencer, Eric or the jock Chas Allen played by Blake Jenner if they weren't vulnerable. In the words of one of the real parents, everything in our family was geared for our kids to be successful. And you can feel the anxiety that sentiment generates in young men without clear paths toward success.

The turning point comes at an outdoor frat party when Spencer says, ever feel like you're waiting for something to happen but don't know what it is? And Warren says, by stealing those books, they'll rise above the pack or flock or whatever animal metaphor you can think of. The film has many including beavers, as in Warren's exhortation - if you don't do this thing, one day you'll wake up wondering who you might have been if you hadn't beavered away your life. It's a nice sight gag when a shopping cart some frat boys set alight sails across the screen behind them. In one shot, you get toxic masculinity, peer pressure and a nihilistic vision of American capitalism.

Writer-director Bart Layton uses a lot of cinematic tricks to pump up "American Animals," and it often feels like an exercise in ironic style. It doesn't have the emotional fullness of a major work. There's no point where you get carried away by the scheme. You're always ahead of the characters, thinking - idiots. And idiots just aren't that compelling. But in the last act, the tone changes, and the film becomes impressive. Ann Dowd as librarian B.J. Gooch doesn't gracefully swoon after she's hazed but weeps and pleads, the camera tight on her face. B.J. doesn't get this is supposed to be like a movie. And suddenly, Spencer, Eric and Chas - if not Warren, who's fine being mean - get that it's not a movie too.

Eventually, they want out so badly that they sabotage themselves at every turn like a dope's version of "Crime And Punishment." Warren's red-pill-blue-pill line in the scene we heard alludes, of course, to "The Matrix." And though he's not explicit, my guess is Layton thinks modern American animals live in a Matrix-like menagerie, rendered weak and incompetent by fantasies of wealth and fame. That one of the books they made it out of the library with is Darwin's "On The Origin Of Species" is a nasty irony in a tale of de-evolution.

GROSS: David Edelstein is film critic for New York Magazine. I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.