Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on September 6, 1999

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: SEPTEMBER 06, 1999

Time: 12:00

Tran: 090601np.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Life with The Doors

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:06

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

BARBARA BOGAEV, GUEST HOST: From WHYY in Philadelphia, this is FRESH AIR. I'm Barbara Bogaev, in for Terry Gross.

On today's FRESH AIR, life with the Doors and Jim Morrison. We talk with Ray Manzarek, The Doors' former keyboard player. He'll tell us about writing and recording some of their biggest hits.

(AUDIO CLIP: SONG EXCERPT, THE DOORS)

BOGAEV: And we'll hear from the man who recorded The Doors and dealt with the damage caused by Jim Morrison's unpredictable behavior. We talk with Jac Holzman, the founder of Elektra Records.

(AUDIO CLIP: SONG EXCERPT, THE DOORS)

BOGAEV: That's all coming up on today's FRESH AIR.

First, news.

(NEWSBREAK)

BOGAEV: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Barbara Bogaev, in for Terry Gross.

(AUDIO CLIP: SONG EXCERPT, THE DOORS)

BOGAEV: The Doors, one of the great psychedelic bands of the '60s. The mythology surrounding The Doors has mostly centered on its lead singer, Jim Morrison, considered one of rock's tortured poets and sex gods.

(AUDIO CLIP: SONG EXCERPT, THE DOORS)

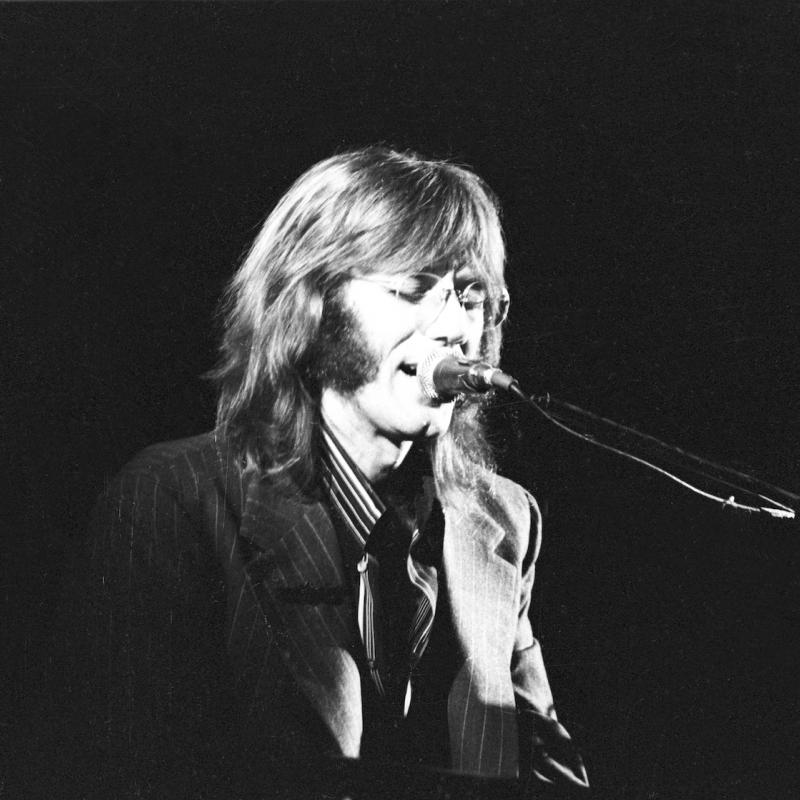

BOGAEV: But instrumentally, The Doors' distinctive sound was based on the keyboard playing of Ray Manzarek. Last summer, Manzarek joined us at the piano to show us how he came up with some of his now-classic organ solos. His memoir, "Light My Fire," had just been published. It's coming out in paperback next month.

The memoir focuses on the years the band performed together, 1965 through 1971, the year of Jim Morrison's death.

(AUDIO CLIP: SONG EXCERPT, THE DOORS)

BOGAEV: Ray Manzarek and Jim Morrison attended UCLA Film School together. Manzarek told Terry Gross that they didn't think of forming a band until they were both out of school.

RAY MANZAREK, FORMER KEYBOARD PLAYER, THE DOORS: Biblically, 40 days and 40 nights after we said our goodbyes after graduation, I'm sitting on the beach wondering what I'm going to do with myself. Who comes walking down the beach but James Douglas Morrison, looking great, lost 30 pounds, was down to about 135, six feet tall, Leonardo -- Michelangelo's David. He had the ringlets and curly hair starting to kind of fall over his ears in gentle locks. And I thought, God, he looks just great.

And I said, "Jim, Jim, come on over here, man, come on, it's Ray, hey, come on." And he said, "Ray, oh, man, good to see you." And, you know, wee did "Hey, buddy," "Hey, pal," you know, high five and all that kind of stuff that guys do.

And I said, "Well, what have you been up to?" And he said, "Well, I decided to stay here in Los Angeles." I said, "Well, good, man, cool. Tell me, what's -- so what's going on?" And he said, "Well, I've been living up on Dennis Jacobs' rooftop, consuming a bit of LSD, and writing songs."

And I said, "Whoa! Writing songs, OK, man, cool. Like, sing me a song," you know. And he said, "Oh, I'm kinda shy." Because I knew he was a poet. He knew I was a musician. He said, "Sing me... " I said, "Sing me a song."

So he sat down on the beach, dug his hands into the sand, and the sand started streaming out in little rivulets. And he kind of closed his eyes and he began to sing, in a Chet Baker haunted whisper kind of voice. He began to sing, "Moonlight Drive." And when I heard those -- that first stanza, "Let's swim to the moon, let's climb through the tide, penetrate the evening that the city sleeps to hide," I thought, Oooh-hooo, spooky, and cool, man. I can do all kinds of stuff behind that. I could do kind of -- (plays riff on piano)

Sort of like, "Let's swim to the moon," you know, "let's climb through the tide, penetrate the evening that the city sleeps to hide."

And I thought, Ooh, I can put all jazz chords, and I can put some kind of bluesy stuff. (plays bluesy stuff)

I said, "Yeah!" And I can do my Ray Charles and my -- you know, and my Muddy Waters, Otis Span influences. And I could do just all kinds of bluesy, funky stuff behind what Jim was singing.

And then he had a couple of other songs, "My Eyes Have Seen You" and "Summer's Almost Gone," and they were just -- they had beautiful melodies to them that would just allow for chord changes and improvisations.

And I said, "Man, this is incredible. Let's get a rock and roll band together." And he said, "That's exactly what I want to do." And I said, "All right, man! But one thing. What do we call the band? It's got no name. We can't call it Morrison and Manzarek. I mean, you know, or M&M, or, you know, Two Guys From Venice Beach, or something."

He said, "No, man, we're going to call it The Doors." And I said, "What? The -- that seems -- that's ridiculous. The Doors? Oh, wait a minute, you mean like the doors of perception, the doors in your mind." (plays riff)

And the light bulb went on. And I said, "That's it, The Doors of Perception." He said, "No, no. Just The Doors." I said, "Like Aldous Huxley." He said, "Yeah, but we're just The Doors." And (plays riff) that was it, we were The Doors. (plays riff)

And that's how the band got formed.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: So when you and Jim Morrison decided to create a band, that left the lead singer and keyboard player. You still needed other musicians. So you ended up finding the drummer, John Densmore (ph), and guitarist Robby Krieger (ph). But you became not only the keyboard player but the bass player too. It was kind of...

MANZAREK: Well, it was of necessity.

GROSS: Tell us that story.

MANZAREK: We had the four of us. I found John and Robbie in the Maharishi's meditation (plays Indian-flavored riff), and kind of an Eastern mysticism. We were into the same thing, the yoga -- the same kind of yoga that the Beatles were into. Like -- and that came out of -- the song "This Is the End" comes out of that.

So we were all seekers after spiritual enlightenment, and so was Jim, of course. But we didn't have a bass player, so I applied my boogie-woogie background, my rock and roll boogie-woogie, because when I discovered boogie-woogie (plays boogie-woogie riff), that was the whole thing. And you just keep that left hand going. You don't do anything with it. It just goes and goes and goes and goes. And the right hand does the improvisations. (plays boogie-woogie tune)

So I had done that over and over and over as a kid. So it was very easy for me to, once we found the Fender Rhodes (ph) keyboard bass, 32 notes of extra-low-sounding low notes, it was very easy for me to do (plays low boogie-woogie bass line). So that's what I did on the piano bass.

Or like "Riders on the Storm" (plays song). And that's what I did, I just over and over, repetitive bass lines that are just like boogie-woogie, it just keeps on going. And it becomes hypnotic. And that was -- that's why Lefty here is -- thank you, he did a very good job. He's not too quick, but he's really strong and solid and plays what he has to play. So Lefty became our bass player.

GROSS: So your left hand and right hand were playing separate keyboards.

MANZAREK: Oh, of course, yes. One was -- I had a Fender Rhodes -- the Fender keyboard bass sitting on top of a Vox Continental organ, and the Vox Continental organ was what I played with my right hand, and the Fender keyboard bass with my left hand.

(AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, "I'M GOING AWAY," THE DOORS)

GROSS: But we'll be right back. This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

GROSS: Back with Ray Manzarek. He's written a memoir called "Light My Fire" about his years as The Doors' keyboard player.

In your memoir, you write a little bit -- you write a lot, really, about how The Doors developed their sound and how you developed your sound as the keyboard player with the group. Let's take an example of one of the songs. Why don't we look at "Light My Fire"...

MANZAREK: Sure.

GROSS: ... which is probably the most famous, or one of the most famous.

MANZAREK: Most famous Doors song, yes, the most famous Doors song.

GROSS: Sure, yes.

MANZAREK: You know, it's that worldwide popular appeal, most famous. And Robbie Krieger's actually the writer of "Light My Fire." So the way we would work on songs is, somebody would bring a song in, and then everyone would go to work on it. It would be like little bees just -- or little things spinning and working and weaving.

So Robbie came in with the song. He said, "I got a new song called `Light My Fire,'" the first song Robbie Krieger ever wrote. What a genius he is! He's just the greatest guy.

"I've got a song called `Light My Fire.'" So he plays the song for us. And it's kind of a Sonny and Cher kind of (singing) Dan-da-dan-da dan-da-dadada-dan-da, Light my fire. And it's, like, "Oh, OK, OK, good chord change. What are the chord changes there?"

And he shows me an A minor (plays A minor chord) to an F-sharp minor (plays F-sharp minor chord). And that's, like, whoa, that's hip. (plays alternating chords) That's cool. And then -- (plays more chords) And that's when he went into the Sonny and Cher part. (plays Sonny and Cher chord progression) (singing) Da-dada-da da dada...

And we said, "No, no, no, no, no, no, no, no, we're not going to do the Sonny and Cher kind of song here, man." And that was popular at the time.

Densmore says, "Look, we got to do a Latin kind of beat here. Let's do something in kind of a Latin groove." (plays Latin chords) And I'm doing this left-hand line. So John's doing -- ka-ka-chunka-chunka, do-dah.

And we set up this Latin groove and then go into a hard rock four (plays hard rock four). And Robbie's only got one verse. He needs a second verse. And Morrison says, "OK, let me think about it for a second."

And Jim comes up with the classic line, "And our love becomes a funereal pyre," you know, "You know that it would untrue, you know that I would be a liar if I were to say to you, `Girl, we couldn't get much higher,'" is Robbie's.

Then Jim comes, "The time to hesitate is through"... in other words, seize the moment, seize the spiritual LSD moment. "The time to hesitate is through, no time to wallow in the mire. Try now, we can only lose."

Whoa, that's kinda heavy. "Try now, we can only lose," meaning the worst thing that can happen to you is death. "And our love becomes a funeral pyre." Our love is consumed in the fires of Agni. And it's, like, God, Jim, what a great verse, man!

So we've got verse, chorus, verse, chorus. And then it's time for solos. So anyway, the verse goes, Time to -- (singing and playing) Ooten do-dah -- You know how that goes. You've heard it a million times. (plays)

And then into the chorus, (singing and playing), Come on, baby, light my fire. (plays)

So it's time then for some solos. We've done a verse, chorus, verse, chorus. Now what do we do? We got to play solos, we got to stretch out. Here's where John Coltrane comes in. Here's where The Doors' jazz background -- John's a jazz drummer, I'm a jazz piano player, Robbie's a flamenco guitar player. And we all said (plays chord), You know, we're in A-minor, let's see, what do we do? (singing and playing) Da-da-da-da-dah.

It ends up on an E, so how about -- (plays) "My Favorite Things," John Coltrane, it's "My Favorite Things." Except Coltrane's doing it in D-minor (plays in D-minor). But the left hand is exactly the same thing. (plays left hand line) It's in three, one-two-three, one-two-three, A-minor, The Doors' "Light My Fire" is in four. We're going from A-minor to B-minor. (plays bass line)

So it's the same thing as (plays Coltrane line, then Doors line). And that's how the solo comes about. And then we just go. (plays) So it's John Coltrane's "My Favorite Things." (plays) And Coltrane's "Ole Coltrane," and then (plays) that's the chord structure.

Then I would solo over it. (plays right-hand riff) Robbie would solo over it. And at the end of our two solos, we'd go into a (plays) a three-against-four. And I'm keeping the left hand going, exactly as it goes. That hasn't changed, that's the four. On top of it is three. (plays three-against-four). And into the turnaround (plays turnaround).

And we're back at verse one and verse two. (plays) And we're back into our Latin groove.

So it's basically a jazz structure. It's verse, chorus, verse, chorus, state the theme, take a long solo, come back to stating the theme again. And that's how "Light My Fire" came about. The only thing left to do was to come up with that little turnaround thing. I hadn't had that yet.

And we said, "Now, how do we start the song? (playing) Do we just jump on an A-minor to an F-sharp, or we -- You know, we going to do that, vamp a little bit?" And I said, "No, no, no, we need something more. We can't just vamp a little bit." And I started this -- I put my box -- Bach back to work, put my Bach hat on, and came up with a circle of fifths. (plays) So I started like this. (plays) Like a Bach thing, like (plays Bach fugue line)

So, same kind of thing. (plays) Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah! B-flat, I'm in -- so I'm in G (plays), D, F, up to B-flat, E-flat, A-flat, to the A, to A-major, A-major, yeah, that's it. And then we'll go to the A-minor. I'm thinking all this to myself.

So that's how the introduction came about. (plays introduction) F, B-flat, E-flat, A-flat, A, and the drums and everything. Jim comes in singing. (plays) And the Latinesque, and then into hard rock. So that's how "Light My Fire" goes. That's the creation of "Light My Fire."

GROSS: And you come up with this great organ solo in the middle.

MANZAREK: Oh, that was just luck.

GROSS: Which is, of course, cut out of the single.

MANZAREK: Right, exactly.

GROSS: Because the -- your producer figured, We got to get this on the radio...

MANZAREK: Right.

GROSS: ... so we've got to do a singles version, and it was, what...

MANZAREK: Yes, we had to cut down six...

GROSS: ... six or seven minute track...

MANZAREK: ... we -- seven minutes, we had to cut down seven minutes to two minutes, and under three minutes, you know, two minutes and 45 seconds, 2:50 would be ideal.

GROSS: So he calls you into the office, plays you his version...

MANZAREK: Yes, well, well, Paul...

GROSS: ... his edited version...

MANZAREK: ... Paul Rothschild (ph), a brilliant genius producer, and Bruce Botnick (ph) was our engineer. Those two guys were -- there were six Doors in the recording studio, the four musicians and Paul Rothschild and Bruce Botnick. Without them, we never would have done nearly what we did.

Paul said, "I'm going to make an edit here, I'm going to do some edits. I'm going to cut `Light My Fire' down from seven minutes to 2:45, 2:50." And I said, "Good luck, man. I don't see how you're going to do it." There's solos, Robbie's solo, my solo, all this stuff. I mean, you're going to have to do little -- the Chinese torture of 1,000 cuts is what he was going to have to do.

You actually had to cut tape in those days, no computers, so you actually cut the tape.

Two days later, Rothschild calls and said, "OK, man, I got it." I said, "(INAUDIBLE) you got it, how did you do it so fast? You got 1,000 cuts." And said, "No, no, no, no, I'm -- just come on in. I'm not going to tell you what I did, how I did it. I just want you to listen to it."

So the song starts -- we're all in the control room on the big speakers at Sunset Sound. The song starts (plays), the regular introduction, and then it's into (plays). And it's going along, and then it -- (singing) Come on, baby, light my fire. And that's going along.

Now we're into the second verse, "The time to hesitate is through, no time to wallow in the mire. Try now, we can only lose, our love becomes a funeral pyre. Everything's going exactly. Come on, baby, light my fire. Nothing has changed, everything is exactly the same. Come on, baby, light my fire, try to set the night on fire.

Now it's time for the solos. I think, Where's the edit, man? And we're into the solos. (plays) And I thought, I don't know where he's going to cut. This is insane. And all of a sudden, where I'm supposed to go (plays), you know, play my organ solo, what happens, it goes (plays) -- it goes to the end of the solos! (plays turnaround) And it's back into the turnaround. And there's, like, not a solo, there's no solos. I'm out. I've got three minutes of solo. Robbie's got two and a half minutes of solo.

It's all gone. It just goes (plays), Da-da-da da-da-da da-da-da dah. And turnaround. (plays) And I think, Oh, no, what's he -- And then we go back into verse number three. (plays) And then we do that exactly as the song is. And then verse number four, Time to hesitate, no time to wallow in the mire, try now, our love becomes a funeral pyre. Come on, baby, light my fire. Come on, baby, light my fire. Try to set the night on fire. Try to set the night on fire. Try to set the night on fire!

And it's the end of the song. And that's it, it's two minutes and 45 seconds long. And there are no solos in the entire song. And I thought, I'm going to kill this guy. I looked at Robbie, and Robbie said, "You want to kill him? Let's kill him."

And Paul said, "Hold it, hold it. Listen, I know the solos aren't there. But just think, you don't know the song, you've never heard the song, you're 17 years old, you're in Poughkeepsie. You're in Des Moines. You've never heard of The Doors. All you know is a two minute and 45 second song is going to come on the radio. It's called `Light My Fire.' Does that work?"

And we all looked at each other and said, "You know what, man? You're right, it does, it works."

BOGAEV: Ray Manzarek. Terry spoke with him last summer. His memoir, "Light My Fire: My Life With The Doors," will be released in paperback next month. He'll be back in the second half of our show.

I'm Barbara Bogaev, and this is FRESH AIR.

(AUDIO CLIP: EXCERPT, "LIGHT MY FIRE," THE DOORS)

(BREAK)

BOGAEV: Coming up, we continue our conversation with Ray Manzarek, former keyboardist with The Doors, and we hear from Jac Holzman, the founder of Elektra Records, which recorded The Doors.

(BREAK)

BOGAEV: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Barbara Bogaev.

Let's get back to Terry Gross's 1998 interview with Ray Manzarek, the former keyboard player of The Doors.

His memoir, "Light My Fire," will be released in paperback next month. It's filled with stories about the unpredictable behavior of lead singer Jim Morrison.

One of those stories is about what happened during the "Light My Fire" recording session. The engineer, Bruce Botnick, had brought in a television and put it in the studio. And when Morrison noticed it, he exploded. Let's hear Manzarek tell the story.

MANZAREK: Bruce Botnick has the Dodgers on, the Dodgers are in the pennant race. Bruce Botnick's a big baseball fan. He's recording with The Doors, he brings his portable television set. He wants to see the game. It's the middle of thee afternoon, Dodgers are playing, and he's got his television. He couldn't put it in the control room, there's too much electronic equipment, and it just -- with the rabbit ears. These are the old days, folks. This is before cable. This is -- people had rabbit ears coming off of the television set.

He couldn't do it in the control room, too much electronic equipment, too much static. He found a good place for it off to the side in the studio area facing the window, the control room window. It wasn't in anybody's way or anything. Everything was fine.

So we're in the middle of "Light My Fire." And it's solo time. And I'm about to go Coltrane and do my stuff (plays). And Jim comes out of the control room -- or out of his vocal booth. You put the singer in a vocal booth. And he starts dancing around. He's having a great time.

Then he comes over to the TV set and he sees the TV set. Then he looks around and notices that it's on. (plays tinkly riff) Yow, God, he's -- And he -- he's -- he freaks out. It's like, What is a TV set on in the recording studio? We're making Doors music here for the first time. This is our first recording session, first time in our lives, we're in the studio, we're doing "Light My Fire." And a baseball game is on the TV set?

Jim picks up the TV set, unplugs the damn thing, and hurls it at the control room window. We freaked, man. Everybody just -- we're in the middle of a -- I'm just going to town (plays), and all of a sudden, it was, like, AAAAAHHHH -- Jim, whoa -- no, God, don't throw it at the (INAUDIBLE) -- (crashing chord)

Hits the control room window. Thank God the control room window is double-thick glass. Bounces off the control room window, falls on the floor and shatters in 500 pieces. (tinkly riff) And that was the end of the session.

And Bruce Botnick comes running out. He says, "Jim, what have you done?" And Jim said, "What's this TV set doing here, Bruce?" "I was watching the baseball game. That's my -- you -- that's my TV set." And Jim said, "No TV sets in the recording studio, ever."

GROSS: You also write in your memoir, "Light My Fire," about, you know, Jim Morrison's period (ph) is like a sexual god. And you write about how, like, he wears leather pants with no underwear so the contours of his manhood can be...

MANZAREK: Yes.

GROSS: ... could be seen under the leather. I wonder what it was like for you to kind of be at the epicenter of this -- kind of like sexual adoration.

MANZAREK: Oh, it was fabulous. It was fabulous. I mean, we made our music, that's what we did. You know, the fact that Jim attracted the little girls was something that I knew he was going to do when I saw him at 135 pounds on the beach. When you start a rock and roll band, and you're about the handsomest guy I've seen -- I didn't say this to him -- the girls are going to love this guy. And the girls did love him, of course. I mean, he was just absolutely sexual and absolutely handsome and snaky and, you know, just that kind of guy that girls like.

You know, I've always wanted girls to like me, but they liked him better. You know, I thought, These glasses, maybe if I didn't have glasses on, you know, it's like the intellectual kind of -- I have to wear glasses, I got bad eyes, you know.

GROSS: Well, it was funny, you know, in the first Doors publicity photo, which you reprint in the book, Jim Morrison is looking very kind of coy and flirtatious, and you're looking very opaque behind large pres -- large probably prescription...

MANZAREK: Sunglasses, yes, yes...

GROSS: ... sunglasses.

MANZAREK: ... prescription sunglasses on top of it, exactly.

GROSS: One of the really big stories in the lore of The Doors is the concert in Miami, where...

MANZAREK: Yes, it is.

GROSS: ... where many people say that Jim Morrison exposed himself...

MANZAREK: Yes, they do.

GROSS: ... and you say he didn't exactly. But he had seen the Living Theater a few days before, and that was, like, the theater group that was experimenting with, you know, breaking down the fourth wall and taking off their clothes in the middle of theater performances, confronting the audience and so on.

And he was influenced by that.

MANZAREK: Yes, he was.

GROSS: So -- (laughs)

MANZAREK: Go ahead.

GROSS: So -- well, what did he say to the audience that got the audience so excited and so expecting him to...

MANZAREK: Well, what he said -- can I -- I don't know if I can...

GROSS: ... expose himself?

MANZAREK: ... say that on the radio here. My goodness.

GROSS: Well, do the clean version of what he said.

MANZAREK: OK, I'll do the -- it's the C-word. He said the C-word, ladies and gentlemen. We won't go any further than that. We're in Miami. It's hot and sweaty. It's a Tennessee Williams night. It's a swamp, and it's a -- yuck, horrible kind of place, a seaplane hangar. And 14,000 people are packed in there, and they're sweaty.

And Jim has seen the Living Theater, and he's going to do his version of the Living Theater in front of -- this is the first time he's been home. He was born in Melbourne (ph), Florida. This is his -- virtually his hometown, and he's going to show these Florida people what psychedelic West Coast shamanism and confrontation is all about.

He takes his shirt off in the middle of the set and says, "You know, you people haven't come to hear a rock and roll... " He's drunk as a skunk, and he didn't tell any of us what he was going to do. If only he'd have told somebody!

He said, "You didn't come to hear a rock and roll band play some pretty good songs. What you -- you came to see something, didn't you?" And they're all going, "Yeah, (animal sounds)." He said, "What'd you come to see? You came to see something that you've never seen before, something greater than you've ever seen. What do you want? What can I do for you?"

And the audience is going like this, you know. I'm playing the piano right now inside the strings. That's how the audience -- it's just rumbling and rumbling. And he said, "OK, how about if I show you my... " C-word?

And all the audience goes screaming crazy. It was, like, madness. And Jim takes his shirt off, holds it in front of him, reaches behind it, and starts fiddling around down there. And you wonder, what is he doing? And I'm thinking, Oh, God, he's going to take it off. And the audience is getting crazier and crazier.

And then Jim whips the shirt out to the side, and he says, "Did you see it? Did you see it? Look, I just showed it to you. Watch, I'm going to show you my... " C-word, again. "I'm going to show it to you. Now, keep your eyes on it, folks." And he whips it out -- Ooh, off to the side again, off to the side again, off to the side, and says, "I showed it to you. You saw it, didn't you? You saw it, and you loved it. And you people loved seeing it. Isn't that what you wanted to see?"

And sure enough, it's what they wanted to see. They hallucinated. I swear, the guy never did it, he never whipped it out. It was, like -- it was like on the West Coast, Jesus on a tortilla, it was one of those mass hallucinations. It was -- I don't want to say the vision of Lourdes, because only Bernadette saw that. But the other people believed, and maybe other people saw it. It was one of those kind of religious hallucinations, except it was Dionysus bringing forth, calling forth snakes.

GROSS: And then you say he said to the audience, "Come closer, come on down here."

MANZAREK: Oh, yes, yes, yes.

GROSS: "Get with us, man."

MANZAREK: "Come on," you know, of course, sure, "Come on, join us, join us on stage." And eventually the -- sure, and they (INAUDIBLE) they started coming, on a rickety little stage, and the entire stage collapsed, sure.

GROSS: What were you thinking?

MANZAREK: It's chaos, it's the end of the world as we know it! It's rock and roll, it's madness, it's the end of Western civilization. Dionysus has come back from 2,000, 3,000 years ago. He has called for the snakes. The people have had a mass hallucination. They've rushed the stage, trying to get their hands on Dionysus to rip and tear him apart.

And I played (plays) -- I played the riot. John and Robbie left the stage, and I just played screaming, crunching organ all over the place, just the way I did when my first piano lesson -- before the piano lesson, when my mom and dad said, "Play the piano," and I went (plays random notes). I did the exact same thing on the organ. I was seven years old, going, YAAAAAAH! and screaming on the organ.

GROSS: Now, was there a part of you that was saying, instead of, like, blah-blah-blah Dionysus, was there a part of you that was saying, My stupid buddy, Jim Morrison, is creating this madness, we'll be lucky if we get off the stage alive?

MANZAREK: There was a part of me that was saying, We're going to get in big trouble. We're in trouble here. But you know what? It's too late to stop it. So why not treat it as a theatrical event, you know? Let's create...

GROSS: Write a score for it.

MANZAREK: ... (INAUDIBLE) -- Let's make our own reality here. If they want theater, here's some theater you folks never thought you were going to have. But we're going to get in serious trouble.

And sure enough, within a week, Jim had been arrested, he had been charged with indecent exposure, open profanity, public drunkenness, lewd and lascivious behavior. And this -- they read this in court, and "simulation of oral copulation. He did take his penis out and shake it. (plays shaking riff) In the courtroom, the audience is going, (INAUDIBLE), and judge going, "Order in the court, order in the court here."

And once they read that in court, I knew it was a total fiasco, because he had never done it. He didn't do it.

GROSS: Ray Manzarek, former keyboard player with The Doors. We'll hear more from him later in the show.

Coming up, what The Doors' record company thought about Jim Morrison's behavior. We talk with Elektra Records' founder Jac Holzman.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

BOGAEV: Ray Manzarek just told us some stories about Jim Morrison's destructive behavior. So how did the head of the record company feel about that?

We asked Jac Holzman, the founder of The Doors' record company, Elektra Records. Terry spoke with Holzman in 1998 after the publication of his book about Elektra called "Follow the Music." Elektra started out as a folk and ethnic music label and first made its mark with such performers as Gene Ritchie (ph), Theodore Bikel, Judy Collins, Tom Paxton, and Phil Ochs.

Elektra's first big hit was The Doors' single, "Light My Fire." What attracted a folk and classical music fan like Jac Holzman to The Doors? Well, one thing was their version of the Brecht-Weill song, "Whiskey Bar."

(AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, "WHISKEY BAR," THE DOORS)

BOGAEV: Terry asked Jac Holzman about the difficulties he faced working with Jim Morrison, who was talented, commercially successful, but often out of control.

JAC HOLZMAN, FOUNDER, ELEKTRA RECORDS: From our standpoint, the difficulties in Jim's life and the way he expressed them were nothing as compared to the magic of the recordings. It was more than "Light My Fire." The first Doors album was as close to a perfect album as I've ever been involved with. That album really pushed the envelope. And I was just so thrilled to be associated with it.

And if there was a price to pay, that was OK with me. I had dealt with some outrageous artists before who had problems, and artists afterwards who had problems. And I found it best to keep my distance, because I'm the person who runs their record company, and I am the surrogate for the audience. And it's my job to make sure that things keep moving and that the artists are given the very best possible circumstances in which to record.

And these are the issues that you have to deal with.

GROSS: So you tried to keep your distance, in part, so you could remain kind of the authority figure and not get too close with anyone.

HOLZMAN: Well, it's -- it makes it difficult if at some point you have to take a stand on something, and you've been hanging out with them all the time. It erodes the special relationship that you have with them. And I think that the Doors appreciated that. I know Jim did. Before he went to Paris, he wanted to have sort of a farewell drinking session with me. Well, I'm smart enough not to have more than two with Jim Morrison, because Jim's big enemy was alcohol.

And he could be a prince. You could take him anywhere. But pour a few drinks into Jim, and he would go from Dr. Jekyll to Mr. Hyde. And it was a real problem. So I would never try to match him drink for drink.

But I remember this evening so vividly, because we were sitting in this bar, and we've each had our second drink. And Jim begins to taunt me. "Jac, you got to go more out on the edge." And I responded, "Jim, it's great being on the edge. The trick is not to bleed." And he sort of paused for a moment, and then we talked about movies.

GROSS: Your record company, Elektra, was coordinating the Doors' tours and club dates. How would you deal with it if club owners got scared by Morrison's behavior and they wanted to cancel a date?

HOLZMAN: That never really happened until after the Miami incident.

GROSS: When he was accused of exposing himself on stage.

HOLZMAN: That's correct.

GROSS: And then what happened?

HOLZMAN: Well, what happened then was that a decency movement began in Florida, and there was a move among concert promoters to cancel Doors' dates. And Doors' dates were being canceled all over the country, and The Doors were in a major funk over this, as well you might imagine they would be.

We just kept our cool, and we kept doing what we were supposed to do, be responsible for their records and supporting the boys wherever we could.

GROSS: As the head of the record company, did you ever think, Oh, well, maybe I should sit down with Jim Morrison and either try to discipline him or have a little talk with him about controlling himself more?

HOLZMAN: I thought that was better left to Ray Manzarek and the other members of the group. My function is not it discipline artists. My purpose is to be the midwife to their music, to support them, to help them in what they want to do creatively. If an artist asks me for an opinion, they know they'll always get an honest one. But I didn't think it was my place to get involved in what was essentially an internal group problem.

I had seen this before. I had had other artists who had problems, and I always let the groups handle them.

GROSS: Now, why did you decide to sign The Doors? What appealed to you about their music?

HOLZMAN: I went to see another group called Love who was on Elektra, and Arthur Lee, who was the essential linchpin of that group, said, "Stick around for the other group that's on the bottom of the bill," and I did. And I wasn't really very impressed. But there was something about the group that kept bringing me back, and it was only later that I figured out what it was.

It was a kind of austerity in their musical line. If I were to compare The Doors to architecture, I would say that they were the Bauhaus of '60s rock and roll. And I think that cleanliness of line and the expressive lyrics and the sheer beautiful simplicity of it is what has made the group last for over 30 years.

GROSS: You were kind of unprepared for the incredible success that their first record had. And you had to call the pressing plants to get more records made very quickly, because there was a big demand for them. What impact did that have on the company, to have this big, sudden demand?

HOLZMAN: It was fantastic, because suddenly, after having struggled for 17 years with folk albums and singer-songwriters that had found increasing popularity, I was now riding the tiger. And the company was catapulted into a leading position. People were bringing artists to us. We got first crack at things.

And the logistics of pressing the records was left to my brother, Keith. And we had relationships with pressing plants all over the country, and we were able to get everything manufactured that wee needed.

But the important thing was that we were able to attract other artists because we had moved up one order of magnitude, I guess, on the scale of record companies. It was heady stuff.

GROSS: When you found out about Jim Morrison's death, what responsibilities did you have? Did you have to take care of his personal effects or anything like that?

HOLZMAN: No. What I had to take care of first was my own emotion. Jim had been so special to me, and the band was phenomenal. And they had played such a vital and pivotal role in the growth of Elektra. Jim had been kind to me and my family, he would remember my son, Adam's birthday and bring him a musical instrument and spend time with him.

So I had to deal with that. But I also realized that I had to deal with what I thought was going to be a media circus. And indeed, it had been for Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin. But I was lucky, I had two days to prepare. I knew about it on a Monday, and it wasn't public knowledge until Wednesday evening.

So I sent my number two man, Bill Harvey, out to the West Coast. We had press releases prepared. We told the staff at the appropriate time. We had to tell Paul Rothschild, who had been their producer for all of the albums except the final one, "L.A. Woman." And we got all of that stuff done. So when the phone calls started coming and people wanted the radio interviews, we had determined that we were going to let The Doors do most of the talking, The Doors and Pam, and we would speak only about what their music meant to us and to their fans.

BOGAEV: Jac Holzman is the founder of Elektra Records. Terry spoke with him in 1998 after the publication of his book, "Follow the Music."

Let's listen to another track from Thee Doors' first album.

(AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, "THE OTHER SIDE," THE DOORS)

BOGAEV: Coming up, keyboardist Ray Manzarek looks back on Jim Morrison's death.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

BOGAEV: Let's get back to Terry's 1998 interview with The Doors' keyboard player, Ray Manzarek.

GROSS: Toward the end of The Doors' life as a band, Jim Morrison could only play, like, about three nights in a row, and he'd just be kind of either spent or just too depressed or manic to -- one or the other...

MANZAREK: No, he wasn't too manic...

GROSS: ... to play after that.

MANZAREK: ... the manic side -- no, it was just -- it was -- his energy was giving out.

GROSS: Right.

MANZAREK: He was depleting his energy with alcohol. And physically, on the first night he was able to do -- he was fine. The second night, he was halfway drinking too much. And by the third night, the booze would catch up with him, and he was just kind of hanging onto the microphone. And he had lost his chi, is what he had lost.

GROSS: He told you he was having a nervous breakdown.

MANZAREK: At one point he said, "I'm having a nervous breakdown," yes, exactly. He said, "I'm going to quit. I'm having a nervous... " I said, "You can't quit, you're not having a nervous breakdown. You're drinking too much."

GROSS: When he went to Paris for what you thought would be some rest and relaxation, he ended up dying there, mysteriously.

MANZAREK: Yes, yes.

GROSS: At the age of 27.

MANZAREK: Yes.

GROSS: What do you know about his death?

MANZAREK: I don't -- I know what -- exactly what I said in the book, I don't know -- really know anything about it. There's a French doctor's certificate that says his heart stopped, whatever that means. You know, he's not breathing. "This corpse is not breathing, therefore it is dead," you know, and that doesn't say anything. That's insane.

People that were there, people that weren't there, Marianne Faithful was there, the Count, a heroin -- a known heroin-addicted Eurotrash European guy, Pam was having sort of a quasi-affair, and needle exchange with the Count. Pam, unfortunately, eventually did die of a heroin overdose.

I don't know that heroin enters into the story of Jim Morrison. It enters into the life of Pamela Curzon (ph). A sealed coffin was buried. Our manager went over to see what the story about Jim Morrison being dead was all about, and he arrived in Paris, and three days later put a sealed coffin into the ground, called me and said, "We buried Jim." And I said, "Oh, my God,l you buried him? You mean, those rumors and those stories, that story about Jim being dead, that's true?

He said, "Yes, it wasn't a story, man. I put the coffin, and Pam was there, and two of his French friends were there, and Alain (ph) and Agnes Varda (ph), and we buried Jim in Pere le Chaise (ph) Cemetery, and we couldn't pronounce the name. In a French cemetery, I don't know what the name of the place is, Ray."

And I said, "Well, how did he look?" He said, "I don't know." I said, "What do you mean, you don't know?" He said, "I never saw the body."

GROSS: You don't believe it wasn't him, though, do you?

MANZAREK: I don't believe -- I don't know what I believe, you know? I believe Jim Morrison's dead. I haven't heard from him in 27 years now. But there's a lot of stories. (INAUDIBLE), how did he die? See, how did he die, we don't know. And quite frankly, I don't care how he died. If he's dead, he's dead, God rest his soul.

However, Dionysus rises again. Dionysus is the god of rising, of resurrection, as is Osiris, the Egyptian god, as is Jesus, the Christ, the god of resurrection for Christians. Jim Morrison is also going to rise again on July 6, the year 2001. They're digging up his grave, and they're throwing him out of the cemetery. The lease is up, a 30-year lease, and they're not going to renew the lease. This is what I've heard, they're not going to renew the lease on Jim Morrison's grave, and his remains are going to have to be removed from Pere le Chaise Cemetery.

GROSS: Wow. Where are they -- where is it -- where is he going to go, do you know?

MANZAREK: It doesn't matter. How disgusting! I mean, it's an awful, terrible thought.

GROSS: It's so odd.

MANZAREK: You know, what are they going to do with -- Well, I'm going to throw him in a pauper's grave, like Mozart, you know.

GROSS: Are they not renewing because there's so many people who come there to make the pilgrimage?

MANZAREK: Exactly, it's a riot going on there.

GROSS: Yes.

MANZAREK: Yes.

GROSS: So did you have to reinvent yourself after Jim Morrison died, and that was the end of The Doors?

MANZAREK: No, I just had to get onto the next thing. I'm the same person I was before. You know, my psychedelic and cosmic vision formed when I was 25, is the exact same one I have today. Would I be telling you -- what I'm telling you today is what I would have told you two weeks Jim -- after Jim Morrison died. I'm the exact same person.

You know, once you open the doors of perception -- I mean, Ray, do you still take acid? No, I don't take acid. Do you still get high any more? You don't need to. Once you open the doors of perception, the doors of perception are cleansed, they stay cleansed, they stay open, and you see life as an infinite voyage of joy and adventure and strangeness and darkness and wildness and craziness and softness and beauty.

So that's how I live my life, and I haven't changed. I didn't really have to reinvent myself. It took a long time to get over Jim's death, however, you know. That was a real sad -- that was a sad, sad period for me.

BOGAEV: Ray Manzarek. Terry spoke with him last summer after the publication of his memoir, "Light My Fire: My Life With The Doors." The book will be out in paperback next month.

FRESH AIR's executive producer is Danny Miller. Today's FRESH AIR was produced by Kathy Wolfe (ph). Our interviews and reviews are produced by Phyllis Meyers (ph), Amy Sallett (ph), Naomi Person (ph), and Roberta Shorrock, with Alan Tu, Monique Nazareth, and Anne-Marie Baldonado (ph). Our engineers are Bob Purdick and Al Banks.

For Terry Gross, I'm Barbara Bogaev.

(AUDIO CLIP, SONG EXCERPT, THE DOORS)

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Barbara Bogaev, Philadelphia, PA; Terry Gross

Guest: Ray Manzarek; Jac Holzman

High: The Doors's keyboard player Ray Manzarek, author of "Light My Fire: My Life with The Doors," talks about his experience playing in one of the most influential bands of the 1960s. Jac Holzman, the founder of Elektra Records, talks about working with The Doors.

Spec: Music Industry; The Doors; Ray Manzarek; Elektra Records

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1999 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1999 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Life with The Doors

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.