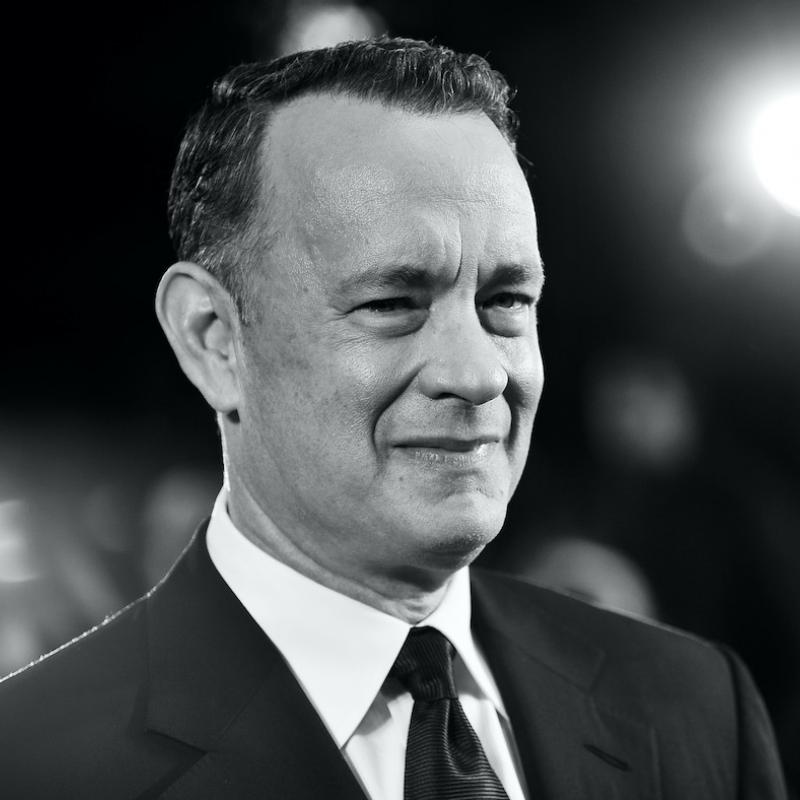

Retired Astronaut and Former Test Pilot Alan Shepard

Alan Shepard was America's first man in space in 1961; the voyage covered 302 miles and lasted 15 minutes. Ten years later with Apollo 14, he made it to the moon, playing golf on the moon's surface. Early in his space career, Shepard was diagnosed with an inner ear syndrome which could have ended his career. Shepard grounded himself in 1963 and became Chief of the Astronaut Office. Later, after a risky operation took care of his ear problem, Shepard returned to flight status, becoming commader of the Apollo 14. Shepard is the author of Moon Shot: The Inside Story of America's Race to the Moon (currently out of print).

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on July 4, 2003

Transcript

DATE July 4, 2003 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Filler: By policy of WHYY, this information is restricted and has

been omitted from this transcript

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Profile: Alan Shepard's contributions to the space program

BARBARA BOGAEV, host:

A new special DVD version of the film "The Right Stuff" is just out, and we're

featuring interviews with some of the early heroes of the space program. Alan

Shepard was the first American in space. In 1961, he rode the space capsule

Mercury 7 to an altitude of 115 miles. Ten years, later Shepard commanded the

Apollo 14 on a mission to the moon. In between those two spaceflights,

Shepard was grounded for medical reasons, but he helped erect the space

program as chief of NASA's Astronaut Office. He was an essential part of the

team that helped America first get to the moon 25 years ago. One of Shepard's

most embarrassing moments was immortalized in the film "The Right Stuff." In

this scene, Shepard is played by Scott Glenn.

(Soundbite of "The Right Stuff")

Mr. SCOTT GLENN: (As Alan Shepard) Gordo. Gordo, I have to urinate.

"GORDO": Urinate? Not...

Unidentified Man #1: Oh, boy.

"GORDO": Urinate? No, we did not think of that. This is only a 15-minute

flight.

Unidentified Man #2: Yeah, well, the man's been up there for hours.

Unidentified Man #3: Could he just do it in his suit?

"GORDO": It might be dangerous. To introduce liquid into the pure oxygen

environment of the capsule and the pressure suit might cause a short circuit.

It could start a fire. No. Tell him he cannot.

Unidentified Man #4: Say, listen, old buddy, they promised we'll stop at the

next gas station. Request that you remain in a holding pattern till then.

BOGAEV: In case you're wondering, Shepard eventually got permission to go in

his suit.

When Terry spoke with Alan Shepard in 1994, she asked him about his first

spaceflight back in 1961. The trip was brief, so he didn't have much time to

experiment with weightlessness.

(Soundbite of 1994 interview)

Mr. ALAN SHEPARD (Former Astronaut): My flight was only 16 minutes. We did

have about 5 1/2 minutes of weightlessness. And the thing which we'd tried to

cram into that 5 1/2 minutes had to do primarily with my ability to actually

control the spacecraft, actually fly it like an airplane because we knew that

so much of the early days of space depended upon the abilities of a pilot, not

only under primary conditions with no casualties, no failures, but also to

practice for situations where the pilot would have to take over in order to

bring it back in safely. So most of the 5 1/2 minutes were devoted to my

actually controlling the spacecraft and reporting how I was doing and that

sort of thing.

TERRY GROSS, host:

How were you doing?

Mr. SHEPARD: I did great, of course. I would...

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: I mean, how did it feel to control the spacecraft while being

weightless?

Mr. SHEPARD: Well, it was a tremendous exhilaration, of course, of being up

there in the first place; also, the second place, the fact that everything was

going well; and then, lastly, the fact that I flew it exactly as I was

supposed to fly it.

GROSS: Was it what you most wanted, to be that first American in space?

Mr. SHEPARD: Oh, I think all of us wanted that. We were a very highly

competitive group to start with. We were all test pilots. We knew that only

one of the seven was going to get to go first. And, you know, everybody

wanted to go.

GROSS: Now after you became the first American in space, you got something

called Miniere's syndrome. Am I pronouncing that correctly?

Mr. SHEPARD: Yes. That's correct. Actually, I had been assigned to command

the first Gemini mission, which was the first two-man mission. Tom Stafford

was going to be my co-pilot. We were probably three or four months into

training cycle when I developed Miniere's syndrome, which has something to do

with elevated fluid pressure in the inner ear which causes dizziness,

imbalance, nausea in some cases. And when we discovered it was more than just

a temporary virus, then NASA, of course, grounded me immediately and said,

`You can stick around if you want. There is maybe 20 percent chance that you

might recover from this thing normally. And if you want to stick around and

stay in training, we'll be happy to have you do that. We'll give you a job

helping Slayton run the astronaut training program.'

GROSS: It must have been devastating for you.

Mr. SHEPARD: Very disappointing; not only the initial reaction to it, the

onset of it, the realization that I wasn't going to fly again right away, and

then continuing to watch the rest of the guys go down to Cape and have all

these great flights and pat them on the head before they went and, you know,

pat them on the fanny when they came back. It wasn't all that much fun.

There was a lot of frustration involved.

GROSS: You were the chief of the Astronaut Office, which meant that you,

among other things, had to choose which men went on the flights. What would

you look for in an astronaut's personality and temperament before deciding to

schedule them for a flight?

Mr. SHEPARD: Well, what we did for the most part was to choose the

individuals who we thought would make the best commander of the flight, and

then ask them which of the available astronauts they would like to fly with.

So to get an idea, we got two folks or three folks, in the case of Apollo, at

least friendly with each other. We made a couple mistakes, but for the most

part, things went along pretty well.

(End of soundbite)

BOGAEV: Alan Shepard from a 1994 interview with Terry Gross. We'll hear more

of their conversation later on in the second half of the show.

I'm Barbara Bogaev and this is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Chris Kraft, "Flight: My Life In Mission Control,"

discusses his work at NASA

BARBARA BOGAEV, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Barbara Bogaev.

The film "The Right Stuff" about the early space program has just come out in

a special edition DVD. One person featured in the movie never traveled into

space. Instead, he was the man in headphones at Mission Control. Chris

Kraft, otherwise known as Flight, was the last stop in the chain of command.

Kraft was a member of the original space task group in charge of NASA's first

major program, the Mercury missions. He directed the first rocket launches,

created Mission Control in Cape Canaveral and was the flight director for all

the Mercury missions, some of the Gemini missions and director of flight

operations through most of the Apollo program. One of the things that Kraft

designed was the tradition of the countdown. When I spoke with him in 2001, I

asked him to describe the seconds leading up to Alan Shepard's first flight.

(Soundbite from 2001 interview)

Mr. CHRIS KRAFT (Author, "Flight: My Life In Mission Control"): This was

the first time that we had a man on the end of a rocket. Nobody'd ever done

that before. You never got serious about any countdown at that time until you

got to T-minus two minutes. That's when you knew, when you went past that

point, you damn well better get ready to launch. But now at that time,

Shepard's heart rate was about 220. I don't know what mine was, but later

flights said mine was about 180. If you don't realize that this is dangerous,

that something bad can happen a lot of the time and that this is the first

time that a man is going to be at the end of a damn rocket and you're not

shaking, you damn well don't understand the problem.

BOGAEV: Now in the second manned flight, Gus Grissom was the astronaut and

everything went off pretty much fine, except for the splash landing. Somehow

the hatch blew off prematurely, the capsule sank and Grissom had a tough time

of it staying afloat. NASA never really did find out what exactly happened.

And there have been two camps; some thought Grissom panicked and hit the hatch

detonator, and others thought that it was some unknown malfunction. After all

the investigations into this, what did you think went wrong?

Mr. KRAFT: I believe Gus. When Gus said, `I didn't hit the button. That

damn thing blew off by itself, and the first thing I saw was water coming over

the sill,' I said that is 100 percent correct.

BOGAEV: You thought that then and you think this now?

Mr. KRAFT: I thought that then and I think it 10 years, 20 years and I will

always think that. Gus was a superb test pilot, maybe one of the best, if not

the best, and there was no question in my mind he told us what happened. I

think a lot of people couldn't figure out how in the world that could happen

because in all the tests we ran after that, we couldn't make it happen. We

shook the thing, we hit on it, we did everything we could, and we couldn't

make it go off inadvertently. But Gus said it went that way, and I believed

him. I still believe him.

BOGAEV: I'd like to back up a little bit back to 1962 to John Glenn's first

flight. There was a problem with his flight. There was a question whether

the heat shield was loose or not. And if it was loose, the capsule would

ignite on re-entry. Could you describe the scene in Mission Control and what

your options were for that flight?

Mr. KRAFT: Yes. When the spacecraft flew over the Cape on the second time,

there was a telemetry signal, a radio signal, coming down from the spacecraft

that said the spacecraft heat shield was loose. And that came from a

measurement of a small switch which moved when the heat shield actually

loosened up and then dropped free, down about three or four feet and there was

a bag there which would act as an impact alleviation device when it hit the

water. I heard that problem as it was presented to me--said, `We see this

signal.' And I said, `Well, we haven't had any noises, Glenn hasn't reported

anything from the spacecraft. He hadn't heard any noises of the heat shield

being loose. We hadn't had any problems controlling the spacecraft in terms

of anything bouncing around. It's got to be a false signal.' So...

BOGAEV: So you had a gut sense that this wasn't a crisis.

Mr. KRAFT: I was absolutely convinced in my mind that it was a false signal,

and that's not unusual in an insurmated(ph) system. Many times the thing

you're trying to use to measure it fails. Not unusual; as an engineer, common

occurrence. So I thought to myself--and I confirmed that by talking to my

other engineers and I talked to Alan Shepard about it, as a matter of fact,

and we all concluded that's erroneous.

Now in comes the chief designer and in comes my boss, and he's listening to

the two chief designers, one from McDonnell, one from NASA. And they're

saying, `Well, we think it probably is wrong also, but what if it isn't?' And

so I listened to those arguments, and they said, `Well, if we keep the

retropack on, the straps that hold the retropack will maybe hold the heat

shield up tight against the spacecraft, at least until it gets into the

sensible atmosphere and then the atmosphere will keep it there. That might

be a better chance and a better thing to do in case, in the 1/10th of 1

percent case, that it might be right.' So I listened to those arguments and I

said, `I don't think so.' Then my boss said to me, `But I think that it's

still a good thing to do, so do it.'

I didn't like that direction, but he was my boss at the time and we left it

on. That was a damn bad thing to do because the reason I didn't want to do it

is because you could have gotten a mock cone coming off that retropack that

was still there and burn a hole in the heat shield. And that was what worried

the hell out of me because we had something like that happen before. So after

that was all over, I tell you what I said, `I know a hell of a lot more about

this thing than they know. I've got a lot better engineers telling me what's

going on than they have. And the next time that they tell me to do something,

they'd better think twice about it because I ain't going to do it unless I'm

convinced it's the right thing to do.'

BOGAEV: Chris Kraft from an interview recorded in 2001. More of our

conversation after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

BOGAEV: Back now to our interview with NASA's first flight director, Chris

Kraft.

(Soundbite from 2001 interview)

BOGAEV: Now a month before the first Apollo mission, during a checkout

flight, a fire broke out in the spacecraft at Cape Canaveral that was manned

by Gus Grissom, Ed White and Rodger Chafey. You were in Mission Control in

Houston.

Mr. KRAFT: Yes.

BOGAEV: What was your experience in Houston during that crisis?

Mr. KRAFT: Well, I was sick in the stomach. I was about as stunned as I've

ever been in my life before or since. It took two or three minutes to realize

that you just killed three men.

BOGAEV: How--when did you first know something had gone wrong? What did you

hear in your headphones or what alerted you?

Mr. KRAFT: I heard some screaming. I heard some confused people on the

launchpad, external to the spacecraft. I heard a voice with which I was very

familiar, say, `We're on fire.' And I heard another voice, which I was very

familiar with, saying, `Get me out of here.' And then I heard silence. And

then I heard people scurrying about, and I was afraid to ask. And then when I

did ask, I got the answer that I knew I was going to get and didn't ever want

to hear.

BOGAEV: Was there anything that could have been done to get the astronauts

out?

Mr. KRAFT: In that spacecraft, it took, at a minimum, two or three minutes

for an astronaut to turn around in his seat, crank a crank, which opened the

hatch. And by that time, under these circumstances, where they were probably

dead within a few seconds, there was nothing anybody could do.

BOGAEV: How did the fire start?

Mr. KRAFT: We never really knew exactly what happened because most of the

wiring in the area where the fire did start, which was below Gus Grissom's

couch on the left side, was burned up. But almost certainly, there was a bare

wire there, and almost certainly there was a spark, and that's all it took.

BOGAEV: Now you write that that fire was the reason that future Apollo

missions were a success, that you owe it to that tragedy. How so?

Mr. KRAFT: I think that the whole team of government and industry were

running as fast as they could to get to the moon. And so they were running so

fast and they thought that that goal was so important that they did things

which were less than the best. And under their judgment, that was acceptable.

After the fire, it was totally unacceptable. And as a result, the pause that

we had to take to prove what happened, to understand what happened, to fix

that environment so it wasn't there anymore and to make modifications to the

spacecraft in many, many critical areas--we were able to do that in the hiatus

that took place after that.

And without those modifications, we would have been a long time getting there

because I think we would experienced a heck of a lot more failures and

probably killed more people in space as a result.

BOGAEV: You write that you envied the astronauts. That after so many years

planning to get a man on the moon, did you wish you weren't staying behind on

the ground?

Mr. KRAFT: To be perfectly honest...

BOGAEV: Uh-huh.

Mr. KRAFT: ...no. I never wanted to go.

BOGAEV: Why not?

Mr. KRAFT: Because I was on every flight. Vicariously, I was on every

flight. They only got to fly once. I got to fly every time they went.

BOGAEV: Do you think you could do it, sit there 43 stories up on top of all

that explosive material?

Mr. KRAFT: Not without being anesthetized.

BOGAEV: Knowing what you know.

Mr. KRAFT: You got that right. I mean, let me tell you, if you don't think

that lighting up millions of pounds of thrust, burning millions of pounds of

propellant every few seconds is dangerous, you don't understand the problem.

And that's true today when they fly the space shuttle like it was when we flew

Alan Shepard on the Redstone rocket.

BOGAEV: Chris Kraft, recorded in 2001. Kraft has a memoir called "Flight:

My Life In Mission Control."

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Former astronaut Alan Shepard discusses his experience

when he went on the moon aboard Apollo 14

BARBARA BOGAEV, host:

Let's continue Terry Gross' conversation with Alan Shepard. When we left off,

he was grounded for an inner ear problem, but surgery cured it and he was

given the go-ahead to return to space. In 1971, he went to the moon aboard

Apollo 14.

(Soundbite from 1994 interview)

TERRY GROSS, host:

How old were you for this flight?

Mr. ALAN SHEPARD (Former Astronaut): Well, actually when I was walking

around on the moon, I was 47 years old.

GROSS: That's pretty old for an astronaut. That's pretty old for a flight to

the moon, isn't it?

Mr. SHEPARD: Well, I think age is very much of an individual thing. I still

feel very young at my current age which is, you know...

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Now before you landed on the moon, you lost your radar and Mission

Control was thinking you should abort, but you didn't. Why didn't you want to

abort?

Mr. SHEPARD: You've got to be kidding. I mean, after going 230,000 miles,

you're going to worry about a little radar? Come on.

GROSS: A little radar. I mean, what was it like for you to maneuver the ship

without radar? What was blinded without radar?

Mr. SHEPARD: Well, actually, let me just back up a little bit. We had a

problem earlier on the way out where we couldn't dock with a lunar module.

That was traumatic. We finally got that resolved and off we went with

permission to land. We started down--we didn't actually start down but we ran

the computer down, open loop, and it refused to go down because there was a

bad switch and so that was point number two. Either one of those would have

ruined the mission, so we were pretty objectively oriented when we came to the

point where during the descent one is not looking at the moon. You're looking

away from the surface, and in order to be allowed to continue below around

13,000 feet or so, one has to have an update from landing radar.

We were down around 20,000, somewhere along in there and we were not getting

updated on the radar and we were being told from the ground that the radar

wasn't working. We said, `Thank you very much. We understand the radar's not

working. We can tell that.' And they reminded us if we didn't have landing

radar in by 13,000 feet, we said, `Yeah, we remember all that stuff,' and it

was getting pretty tense and pretty close. Finally some bright young guy in

the Control Center said, `Hey, this landing radar is working, but it's locked

on infinity. You haven't recycled. Pull the circuit breaker and see what

happens.' So we pulled the circuit breaker and, sure enough, the landing

radar came in within a matter of, you know, maybe a half a minute or so to

spare. We go on down and land, and we're shutting off the switches and my

co-pilot, Ed Mitchell, said to me, `Alan, what were you going to do if the

landing radar was not in at 13,000 feet?' And I said, `Ed, you will never

know.'

GROSS: Well, what did you plan on doing?

Mr. SHEPARD: I think I would have gone down at least to the point where we

could have pitched over and taken a look at the surface because had great

faith in our ability to land from almost any off-nominal case, we practiced

that in the simulator for hours and hours and hours, and so I had a feeling

that if I could just see it and realize I wasn't running into any mountains or

anything that I probably would have gone down.

GROSS: What surprised you most about how the surface of the moon looked?

Mr. SHEPARD: I don't think we had any surprises about the actual surface of

the moon, about the barrenness. We had looked at pictures of our landing site

taken by previous missions. We had worked with models that were made from

those pictures. We knew the general configuration of where the craters were

supposed to be. We knew the objective of Cone crater which was the one we

climbed up the side of to get rock samples. There weren't any surprises

there.

The surprise I had was standing on the surface after we'd been there for a few

minutes, having a chance to rest a little bit and looking up at the Earth for

the first time. You have to look up because that's where it is. And the sky

is totally black and here you have a planet which is four times the size of

the moon as we look at it from the Earth and you also have color. You have

blue oceans and brown land masses, the brown continents and you can see ice on

the ice caps in the North Pole and so on, and just an absolute incredible

view.

And then you say, `Hey, that looks a little small to me. It looks like it

does have limits.' It's a little fragile, you know? Down here, we think it's

infinite. We don't worry about resources. Up there, you're saying, `Gosh,

you know, it's a shame those folks down there can't get along together,' and

think about trying to conserve, to save what limited resources they have. And

that was just very, very emotional. I actually shed a couple of tears looking

up at the Earth and having those feelings.

BOGAEV: Alan Shepard talking with Terry Gross. We'll hear more after a

break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

BOGAEV: Back now to Terry's 1994 interview with Alan Shepard.

GROSS: What was the best advice that you got from astronauts who'd been to

the moon before?

Mr. SHEPARD: Probably, `Hey, it ain't so tough after all, fellows, so go up

there and relax and have fun.'

GROSS: One of the things you did on the moon was to hit a couple of golf

balls. And where did the golf club come from and the golf balls and why'd

you do it?

Mr. SHEPARD: Well, I enjoyed the game of golf before I went, and I tried to

think of something that would demonstrate the fact we only had one-sixth

gravity which means the ball's going to go six times as far for the same

club-head speed. There's no atmosphere, so the ball is not going to hook or

slice. And the time of flight is going to be six times as long. So I started

thinking about it and very quickly realized that we had a collapsible handle

there, aluminum handle, we used with a scoop on the end, and we used that to

scoop up samples of dust and we put them in a little bag and marked the bag

and bring it back. We used that 'cause it's very difficult to bend over and

get a sample from a virgin dust, but that would have been left up there. So I

took a look at it and it was about the same as a length of a shaft of a number

six iron. So I got the head of a number six and cut it off and had a pro put

a little fitting on it to snap on the end of this club. And I had the club

head and the two golf balls in the pocket of my suit.

I had practiced before we went. I got the boss's permission to do it, and at

the very end of the mission, when all was completed, I snapped the club head

on the handle, tossed the two golf balls down in the dust, kind of teed them

up a little bit and took a whack and did it in front of the television camera.

So we have a great picture in the book of this ball sailing up and off into

the black sky. The suit was kind of cumbersome and I couldn't swing as hard

as I wanted. So it probably would have gone maybe 30, 35 yards with one hand

shot here on the Earth, but it went over 200 yards. The time of flight was

like 40 seconds. Just an absolute thrill for me to do that. And in the book,

you actually see a picture of the golf ball still in the frame which is kind

of cute.

GROSS: And one of the things that really amazes me about your life is that,

OK, you're the first American man in space, and then you walk on the moon, but

when you were young, you went to school in a one-room schoolhouse. It seems

like such an enormous gap between a one-room schoolhouse and a walk on the

moon.

Mr. SHEPARD: Well, that's true, but I sense that there is something here

that was helpful to me. I remember, of course, that being in a one-room

school with one teacher, there was a tremendous amount of learning time there;

very, very strict teacher, as I recall. She was about eight feet tall and she

had a long yardstick that she used to whack our knuckles with, but there was a

sense of discipline instilled at that time which I responded favorably to.

And I think that sense of disciple obviously served me in good stead going

through the Naval Academy, served me in good stead as a pilot, as a test

pilot, as an astronaut. So maybe, you know, that one-room school thing wasn't

so bad after all.

GROSS: Were there airports around you when you were growing up?

Mr. SHEPARD: There was one fairly close by. In high school, I used to work

at that airport on weekends. I'd ride my bike up and push airplanes in and

out of the hangars and get a free ride once in a while.

GROSS: Did you love it?

Mr. SHEPARD: Oh, yeah. I've always wanted to fly. I built model airplanes.

Lindbergh was my hero when he flew across the Atlantic and very, very

fortunately we're talking about Apollo 11. When the Apollo 11 launched, I was

at the Cape standing by myself over in a VIP observation section. A figure in

a pair of fatigues and an old sailor hat turned upside down came over and

reintroduced himself as Colonel Charles Lindbergh. I had met him before but

only briefly, but that moment, the two of us stood there and nobody bothered

us. Hey, we were there for 15 or 20 minutes without interruption, and I was

telling him at that time as my hero how much he had meant to me and how much

he encouraged me indirectly to become involved in aviation, and he said very,

very graciously, `Well, obviously, Captain'--at that time, he said, `you're

doing the same thing for the people who are going to fly in space tomorrow, to

the planets and beyond,' and it was a very poignant moment, one which I will

never forget.

GROSS: Alan Shepard, thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. SHEPARD: My pleasure, Terry.

BOGAEV: Alan Shepard, recorded in 1994. A new special edition of "The Right

Stuff" is just out on DVD.

(Credits)

BOGAEV: For Terry Gross, I'm Barbara Bogaev. I hope you have a great Fourth

of July.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.