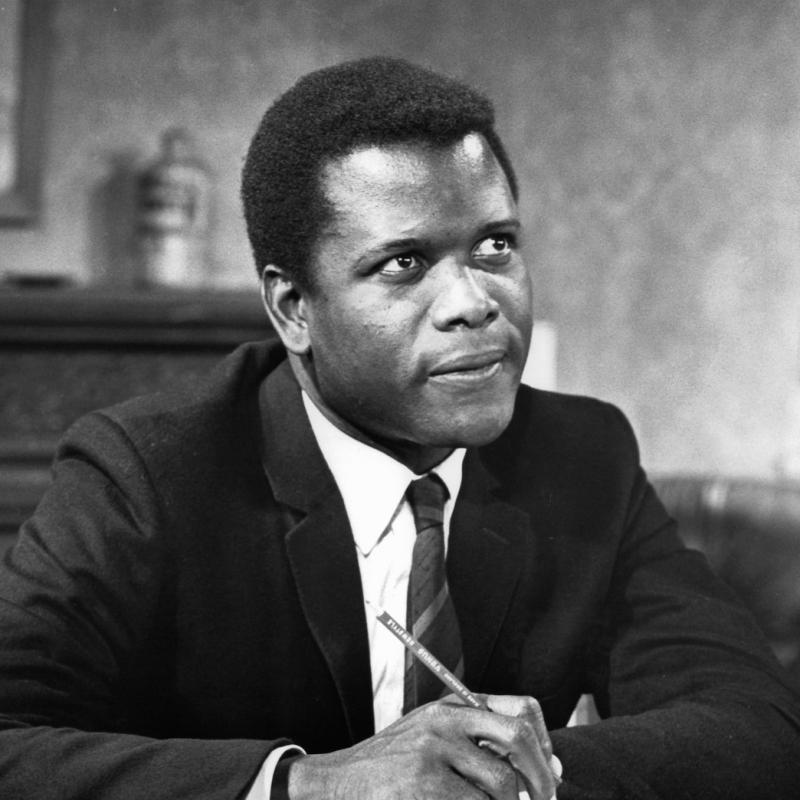

Actor Sidney Poitier.

Actor Sidney Poitier. He is the leading African-American actor of his generation. He was the first, and so far, the only African American to win the Academy Award for Best Actor which he did in 1963 for his performance in “Lilies of the Field.” His other films include, “The Defiant Ones,” “A Patch of Blue,” “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” and “To Sir, With Love.” He’s written a new autobiography, “The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography” (Harper).

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on April 18, 2000

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: APRIL 18, 2000

Time: 12:00

Tran: 041801np.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Sidney Poitier Discusses `The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography'

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:06

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: From WHYY in Philadelphia, I'm Terry Gross with FRESH AIR.

On today's FRESH AIR, Sidney Poitier. He grew up poor on a small island in the Bahamas and went on to become the most famous African-American actor of his generation. Some of his best-known films, including "The Defiant Ones," "In the Heat of the Night," "Lilies of the Field," and "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner," address the racial issues of the times. He has a new memoir.

And Maureen Corrigan reviews "Ravelstein," the controversial new novel by Saul Bellow.

That's all coming up on FRESH AIR.

First, the news.

(BREAK)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Sidney Poitier has said that he always believed that his work should convey his personal values. When he started making movies in 1949, it was hard for African-Americans to get significant film roles. It was even difficult to get small parts that weren't stereotyped.

But in the '50s and '60s, Poitier starred in a string of films that addressed the racial tensions of the time, films like "The Defiant Ones," "In the Heat of the Night," "Lilies of the Field," and "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner." In 1963, he became the first African-American to win an Academy Award for best actor, and he remains the only African-American who has won in that category.

In the '70s, Poitier directed such films as "Buck and the Preacher," "Uptown Saturday Night," "Let's Do It Again," and "Stir Crazy." He's made few films since the end of the '70s.

Now he's written a memoir called "The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography." Poitier grew up in the Bahamas on Cat Island and Nassau. His family was poor. He was born in 1924 and arrived prematurely, weighing only three pounds. His father prepared for his baby's imminent death by buying a little casket. His mother went to a fortune teller.

SIDNEY POITIER, "THE MEASURE OF A MAN": The soothsayer said to my mother, who was deeply concerned about my survival, because I was, in fact, born to my mother with the assistance of a midwife, I was considerably less than three pounds. Anyway, her great trepidations for my survival were such that she was the only person standing in that regard. As a matter of fact, most of the others thought that I should be let go, because the chances for my survival were few.

Anyway, she stood alone, and she dressed herself, and she went out in search of help. Anyway, the soothsayer went through whatever the procedures were for such people, and she told my mother as she came out of what appeared to have been a trance, I'm told, not to worry about me, that I would live, and I would -- (laughs) I would walk with kings, she said to my mom, and that I would travel the world. And my mother's name will be known and heard in all the corners of the earth.

That's what she said.

GROSS: What effect did that have on your parents? And did they -- well, how old were you when they conveyed this story to you, and did you grow up with this story in the back of your mind?

POITIER: I did not grow up with at the back of my mind, but it was passed on to me many years later, obviously, and infinitely before I started in the theater world. But it was said in very ordinary family conversation. It was dropped one day. And I heard it, and it was not brought to my attention in terms of something I should keep my eye out for, you know, it was just mentioned. But it never stayed with me in any meaningful way.

GROSS: Would you describe Cat Island, the island in the Bahamas where you grew up?

POITIER: Cat Island is one of many, many islands in the Bahamas. The Bahamas is now an independent country. But in the time of my youth, and for many, many years before, it was a colonial possession of the British Empire. And it's an island 46 miles long and about three miles wide. The population was very small, that -- during my early years it was barely over 1,000, if that many. Today it is still quite small, it is about 800 -- I mean, about 1,800 people.

It's a -- it's difficult to describe in that words would be hard to find to convey the beauty of it. You know, we have the most extraordinary beaches in the world. The water is of a color and of a luminance that is absolutely striking. Now, I grew up with it, and I had to travel the world to find that there were no other places comparable, at least to my recollection.

GROSS: And describe your house for us.

POITIER: The house. The house was a tiny, four-room structure with thatched roof made from palm leaves. My dad, with the assistance of local people, built the house. It was -- it had no electricity, obviously, because there was no electricity on the island at all. There was no running water, so consequently we had no bathrooms and we had no kitchens attached to the house. The kitchen was some several feet -- several yards away from the house, and the -- we brought water, for instance, from 200 yards away for bathing purposes or for cooking purposes. And all other bathroom functions were accommodated in the outdoors.

The life was such that you walked everywhere you went, and if you had any heavy loads to carry, you would use a mule or a horse or a donkey and stuff like that.

GROSS: When you were 10, your family moved to Nassau, I think because there was, what, a crop failure on the island, or...

POITIER: Well, they were tomato farmers, that's what (inaudible). And they sold to the middle guys in Florida. And they did that for many, many years. And when I was about 9 1/2 or so, the U.S. government in Florida, on behalf of the Florida tomato growers, placed an embargo on tomatoes coming out of the Bahamas for reasons, I suppose, beneficial to the local farmers in Florida. But that devastated the whole farming of tomatoes in the Bahamas, throughout the islands in the Bahamas, and especially on Cat, and which affected my father.

And he, having no other means of making a living, had to move the family to Nassau, which was and still is a tourist community and a tourist economy. And he had to find work as best he could somewhere in that new culture.

GROSS: What kind of work did he find?

POITIER: Well, not much. He found a job ultimately working for someone in a bicycle store. And he wanted to continue farming, but the soil available was not resilient enough to be useful.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Sidney Poitier, and he has a new book called "The Measure of a Man."

You left for Florida where your brother was living with his family when you were age 15. You planned to stay with him. You didn't stay for long. What was it like to face Southern segregation?

POITIER: Well, it was -- (laughs) it was an experience, I can tell you. There was some semblance of it Nassau when we moved from Cat Island to Nassau. There was none of it, none, absolutely none of it on Cat Island. I never developed any sense of what color would eventually come to mean in the other parts of the world. The first place outside of Cat Island would have been Nassau. And in Nassau, there -- it was a fairly modern tourist community, and the majority of people were black. There was a governmental infrastructure that consisted of a community of whites, mostly English people. They controlled the government, they controlled the economy.

And I found sufficient comfort within the bounds of the black community, and was really unprepared for what I found in Florida at the age of 15.

GROSS: Did you do things in Florida that were considered terrible mistakes because you didn't understand what segregation meant?

POITIER: I remember once my brother, with whom I was living once I had arrived there, helped me to get a job within a matter of weeks at Burdyne's (ph) Department Store. And at Burdyne's Department Store I was given a delivery job because I could ride a bicycle. And I used to ride the bicycle from downtown Miami to Miami Beach to deliver packages for the pharmaceutical division of the store.

I went to Miami Beach once to take -- as a matter of fact, on my first day, to take a package to a home. I had the address, and I went to the address, and I rang the bell. And a lady came to the front door, and she saw me standing there. (laughs) And I said, "Good evening, ma'am, I came to bring you your package." And she slammed the -- no, first she said, "Get around to the back door."

Well, I -- listen, I'm 15 years old, I don't know the rules. And I couldn't understand why I needed to go the back door, because there she was, standing there in -- at the front door, and there I was, smiling, with the package in my hand, and expecting her to take it. And I said, "Well, here I am, ma'am, and here's the package." And I handed it to her. And she screamed at me to get around to the back door.

So she slammed the door in my face at that point. And still not understanding fully, I decided that the best thing to do was to put the package down on the steps. And I left it there. And I left.

And I went home. Actually it was two days later, I returned from my work at home, and it was in the evening, and it's -- the house is dark. And I wondered why there were no lights on in my brother's house. And as I approached the front door, the door opened suddenly, and my sister-in-law grabbed me and pulled me in and pulled me to the floor, where the rest of the family was, kind of like huddling. And I didn't know what the reasons were.

And she said to me, (laughs) "What did you do?" I said, "I don't -- I didn't do anything. What do you mean, what did I do?" She says, "What happened?" And she explained to me that the Klan had come to the house looking for me. And that was like an introduction, first of all, to the term "Klan," I never heard it where I came from. And what they were was dispensers of fear, obviously. And my brother's family was quite subject to that that evening.

And my curiosity was such that I wondered. I wasn't so much concerned about the Klan, because I had no experience and no frame of reference. What I was concerned about was how -- the effect it had on the family.

And stuff like that. There were other instances and incidents in Florida that were representative of the time, you know. America was a different place in 19 -- early 1943.

GROSS: My guest is Sidney Poitier. More after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

GROSS: Sidney Poitier is my guest. He has a new memoir called "The Measure of a Man."

You didn't live in segregated Florida for long, you didn't want to deal with the police, the Klan, segregation. You went to New York. When you went to New York, did you have any thoughts about acting? I mean, that's where you started to act. Did you go with any intention of doing that?

POITIER: No, I had no intention of doing that, as -- none at all. I went to New York because I presupposed it to be different from Florida. And, in fact, it was. I had heard stories about Harlem, not so much New York, Harlem, because the stories that I heard in the Bahamas, in Nassau particularly, was of this incredible place called Harlem. And it was supposed to be magical and all that stuff.

And so when I went to New York, I -- that's the place I wanted to go, because I understood it was a kind of remarkable place.

GROSS: Now, when you got to New York, you didn't have much in the way of money. I think you were arrested once for vagrancy. Where were you sleeping?

POITIER: I was sleeping in, I think, Pennsylvania Station. Was it Pennsylvania Station or Grand Central Station? I think Pennsylvania Station. And I had no place to sleep, and it was winter, and I was sleeping on a bench in the train station. And I was obviously able to use the bathroom for washing up purposes and stuff. And it was a comfort to be able to do that, since I was in a winter that was ravishing me. I had never experienced a winter in my life. I came from a area where the climate was almost always in the 70s and 80s and sometimes in the 90s.

And I was awakened by a policeman once and arrested. And he took me to the station house in 33rd Street, and they kept me overnight. They took my fingerprints, (laughs) they sent it off to Washington, I think. And I had to sleep there. And the next morning word came back that I was clean, I was fine, you know, not wanted anywhere. (laughs)

GROSS: Your first audition was as a result of a classified ad that you'd read for the American Negro Theater, which was looking for performers. You say when you got to your audition you had trouble just reading the script. You certainly hadn't been in an audition before. You had no training. You didn't have much schooling either.

POITIER: No, I didn't.

GROSS: How much schooling did you have, and what were your reading skills like at the time?

POITIER: Well, my schooling, I went -- I started school in Nassau at the age of 11, and I had to quit. Actually I started school at the age of 10 1/2, like two weeks after I arrived. And I had to quit at the age of 12 1/2 because my father was not a man of material means, and therefore every hand in the family needed to lend itself to the family's survival.

So I had to go out to get a job, and I did, in fact, get a job at 12 1/2. I suppose that my folks anticipated my eventually going back to school, but it never happened. So that when I got to New York, I'm able to read, but very, very, very -- I can't imagine what level, what grade level. But it wasn't terrific.

So when I went into this place -- I could read, for instance, the want ad pages, and I could recognize words like "janitor" and "dishwasher" and stuff like that. Just across the page from the want ad page, was the theatrical page, and there was this sign that said "Actors wanted." And I went to this address. I said, Maybe I can -- I tried dishwashing and janitors and all that stuff, maybe I'll try this.

And I went there. And there was a gentleman there, alone in this place. It looked like -- well, it was an empty room with lots of empty chairs and a small, what I've learned, was a stage. And he asked me, he said, "Are you an actor?" And I said, "Yes, I am." And he said, "Where have you acted?" I said, "In Florida." (laughs) And he said, "OK." He gave me a script and sent me up on this little stage. And he said, "Turn to page 28," and I did.

And on 28 I saw that there was a name, John, and underneath the name John was an awful lot of writing. And these -- I supposed these were the words that John would be saying. And then was another part named something else. And he was going to read those parts, he said. So he told me to look it over, take a second, look it over, and when I was ready, to let him know.

So I read the page and then the following page, and then I said, "OK, I'm ready." And he said, "OK, you start." I said, "All right." (laughs) And I started reading.

Well, of course I had never read for anyone in my life except maybe in the elementary area my first year in school in Nassau. So I started out, I said, "So -- where -- are -- you -- going -- tomorrow... " (laughs)

GROSS: (laughs)

POITIER: So the chap, (laughs) I guess his eyes flew open, and he looked up on the stage, and it all came to him, you know, that I was a fake. (laughs) So he came running up onto the stage and he snatched the script out of my hand, and he grabbed me. I was a kid, you know. And he spun me around, and he grabbed me by the scruff of the neck, and my belt in the back, and he marched me to the door.

And on the way, he said -- these were his words, as I remember -- he said, "Get out of here and stop wasting people's time." He said, "Why don't you go out and get yourself a job you can handle?" And as he opened the door and as he chucked me out, his last line to me was, "Get yourself a job as a dishwasher or something."

Well...

GROSS: Well, why did you come back for more after that?

POITIER: Because -- oho, I mean, as I'm walking down the street heading to the bus stop to take a bus toward the area where the unemployment -- where the employment offices were, where I would be going to get a dishwasher's job, I said to myself, How did he know that I was a dishwasher? That's how I made my living in New York. And I remembered not having told him that I was a dishwasher.

So I concluded that he presupposed that that would be my limit. I would fall comfortably in that frame, or some such frame. My potential was characterized by his suggestion. And I thought that I cannot let that happen. I would be less than I would like to be if he turned out to have been prophetic when he made that comment.

So I decided, as I headed for the bus station, that I was going to become an actor. I was so offended by what he said. And I was going to go back and show him that he was wrong in his assessment of me.

That's precisely how it happened. (laughs)

GROSS: Sidney Poitier. His new memoir is called "The Measure of a Man." He'll be back in the second half of the show.

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

GROSS: Coming up, becoming an actor. We continue our conversation with Sidney Poitier. And Maureen Corrigan reviews "Ravelstein," the new novel by Saul Bellow.

(BREAK)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR.

I'm Terry Gross, back with Sidney Poitier. He's written a new memoir called "The Measure of a Man." He was born in the Bahamas on a small island which had no electricity. He didn't see his first film until age 11, after his family moved to the larger island of Nassau.

I asked Poitier if he liked movies.

POITIER: Well, I didn't understand them, you know. The first one was a complete bafflement. I had never seen a movie, never. I had -- I didn't know about movies. I never heard -- You know, most of what I knew about life on Cat Island was picked up from, you know, adult conversations, you know, snippets from adult conversation and stuff.

And I didn't know anything about movies. When I arrived in Nassau, I quickly made friends with the local guys my age, you know, the 10-year-olds, the 11-year-olds, where we had found a place to live. And they took me -- they had asked me had I ever been to the -- what they called in those days -- there's a -- the movie house was called a cinema. Had you ever been to the cinema? I said, "No, I haven't." And they said, "Well, we're going to take you."

Well, I didn't want to say to these guys -- because I didn't know what cinema meant -- I didn't want to say, What is cinema? So I just said, "OK." (laughs) They took me, and we went to this place, and then the lights went down, and suddenly up on the screen came writing, you know, stuff, just writing about -- and I was looking at this writing. And suddenly it stopped, and there were images, and there were -- and I was fascinated, because the images were of people.

And not only of people, but there were cows, lots and lots of cows, because this was a Western. And I was sitting there absolutely overwhelmed...

GROSS: Right.

POITIER: ... because I couldn't understand how all those people and all those cows could be in this one building, see.

GROSS: (laughs) Let me get back to your audition. So, you know, you were told, like, Don't come back, go be a dishwasher, and you decided you were going to prove that this guy is wrong. What did you do to try to improve your auditioning skills before going back to prove that this guy was wrong and that you could do it?

POITIER: Well, my first job was to -- because I had this Caribbean accent, as you -- I'm sure you're acquainted with what (inaudible)...

GROSS: Well, let me just stop you there and say I can hear the accent much more in this interview than I hear it in movies.

POITIER: Oh, yes, well, I had it very intensely, so much so that he made a remark about it. And I knew that, from what he had said, that I had to do something about that first and foremost. So I saved up enough money to buy a radio, and I thought that the best way to correct it was to listen to a radio, here in America, and try to learn the sounds, the pronunciations and stuff from people I heard on the radio.

And I did that, and I listened to the radio between dishwashing -- in terms of -- in other words, when I'd get home, wherever I was sleeping, I would plug in this little radio, and I would listen until I fell asleep. And whatever was said on the radio, I would repeat it, like a parrot. (laughs) And I would just listen and repeat and repeat and repeat and repeat. And it took some months (inaudible) the heavy A in the Caribbean speech and the rhythmic, sing-songy patterns began to fade, and I began to develop at least the rhythm and pronunciation of how people spoke in the U.S.

GROSS: So, so you patterned yourself on radio announcers.

POITIER: Yes. As a matter of fact, there was a gentleman in those days by the name of Norman Brokenshire (ph). And I listened to him. He had a very arresting voice, and I liked the way he spoke. And I listened to him an awful lot. Didn't always understood what he was saying, but (laughs) I listened a great deal, and I learned pronunciation of words that I was studying, I was trying to learn what the words meant.

GROSS: So you went back to the American Negro Theater Company and auditioned a second time?

POITIER: Yes, (laughs) I certainly did. That was my aim. I went back six months later and had to audition. But I was really -- not really prepared, because I didn't have a scene or a monologue from a play. I didn't know that one could buy such things in certain bookstores. So I bought what (laughs) I thought would be appropriate for an audition. I bought a "True Confessions" magazine. (laughs) And I memorized two or three paragraphs of this -- of one of the stories in this thing. (laughs) And I didn't know any better.

So I got up on the stage, and I'm reading this thing. And I was hardly through the first paragraph when they stopped me. Oh, my God, just thinking about it.

GROSS: So it's amazing, really, that you were able to actually get a part after all of this. What -- what -- just tell me, what was the thing that you did that you think convinced the right people at the theater company to give you a shot?

POITIER: They didn't give me a shot. They rejected me after they saw my audition, and I made some observations myself while I was there at -- Mind you, this now -- to put you in proper focus, the first place I went to when I was given the first audition, and the guy threw me out, it was the American Negro Theater, and it was located on 135th Street near Lenox Avenue.

They were in the process -- I had no knowledge of this, of course -- they were in the process of moving to a much larger space on 127th Street, and that's where I went for this -- for the second audition. And they had a larger stage and they had a wonderful auditorium, and they had many seats. I think the first place on 135th Street had probably 40 seats, 45 seats, maybe 50. This new place had at least -- oh, they could hold at least 150, 200 people.

Anyway, I noticed that they did not have a janitor there. So when they rejected me the first time, after licking my wounds for a while, I went back a few days later and I proposed to them, since they didn't have, and it appeared -- as it appeared to me, a janitor, I would do the janitor work, which I perceived as being not a great deal of work, because I would just maybe mop the stage down from time to time and do the sweep-up and get the garbage out, which I could do in a half hour or so, or maybe an hour.

And I proposed that I would do the cleaning-up stuff if they would let me come and study. And the people to whom I was speaking, they were the administrators of the American Negro Theater at that time, and they were somehow impressed with my determination. And they said, "If you want to study that bad, that badly, you -- OK, you can come in." And so they had -- they got -- they took me in, and I would -- I was the janitor.

GROSS: My guest is Sidney Poitier. More after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

GROSS: My guest is Sidney Poitier. He has a new memoir called "The Measure of a Man."

Let me advance the story a little further and take you to the early part of your movie career, specifically to "Blackboard Jungle," which was released in 1954. This was an important film for you. You had one of the leads in it. This is a -- like, the most famous high school film, I think. Opens with "Rock Around the Clock," Glenn Ford plays the new teacher at a school just filled juvenile delinquents.

And in your first scene, he catches you and some of the other guys smoking in the bathroom. You're washing your hands with your back turned toward the teacher for most of this scene. Let's hear this scene.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "BLACKBOARD JUNGLE")

GLENN FORD, ACTOR: What's your name, wise guy?

POITIER: Me? Miller. Gregory Miller. You want me to spell it out for you so you won't forget it?

FORD: No, no, you don't have to do that. I'll remember (inaudible).

POITIER: Sure, chief, you do that.

FORD: Or maybe you'd like to take a walk down to the principal's office right now with me. That what you want?

POITIER: You're holding all the cards, chief. You want to take me to see Mr. Warneke, you do just that.

FORD: Who's your home period teacher?

POITIER: You are, chief.

FORD: Well, why aren't you with the rest of the class?

POITIER: I already told you, came in to wash up, chief.

FORD: All right, then wash up. Just cut out that "chief" routine, you understand?

POITIER: Sure, chief. That's what I been doing all the time. OK for us to drink (ph) now, chief?

FORD: I don't want to catch you in here again.

POITIER: Suppose I got business here, chief?

FORD: Look, how many times do I have to tell you, let's go, huh? Come on, let's go.

(END AUDIO CLIP)

GROSS: Sidney Poitier, how did you like your role in "Blackboard Jungle"?

POITIER: I liked it, I liked it. This young guy that I play, he was really on the cusp of finding himself in useful ways, or losing himself to forces he couldn't quite understand by then. And so he had some complications, he had some complexities, he had some depth to him. And I liked playing him.

GROSS: Now, you, you became the African-American leading man in the '60s. What were some of the things that you felt you weren't allowed to play or express as an African-American leading man in the '60s in Hollywood?

POITIER: I -- that is a very good question, and the true answer is, I have no such imagery of what I was not able to express, because taken -- taking the times as they were, the fact of my career was in itself remarkable.

GROSS: Right.

POITIER: Just the fact of it, you see. It would have been a luxury I would not have spent much time on trying to determine what was missing. What was missing was not so much for me, but what was missing for the overwhelming majority of other minority actors at the time.

GROSS: Well, well, I'm glad you brought that up. What were some of the things you heard from your fellow actors at the time about stereotyped roles that they had to play in Hollywood, when you, when you came to Hollywood?

POITIER: Yes, well, you know, most of us, I think, were obliged to play what was available. I did not, I did not take advantage of that. I couldn't. It was not what I needed to do for my life. I had elected to be the kind of actor whose work would stand as a representation of my values.

GROSS: Let me talk with you about a scene that I think represents the kind of values that you're talking about. This is a scene from "In the Heat of the Night." In that film, Rod Steiger plays a local police chief in a Southern town. You're a homicide cop from Philadelphia passing through this Southern town, but you're arrested for being suspicious because you're a black man from out of town carrying money in your wallet.

The police chief doesn't really believe that you're a cop, so he calls your boss in Philly, and your boss suggests that you stay in this small Southern town to help them solve this big murder case that they're working on, because they don't cops who are nearly as experienced as you are.

So in this scene, you and Rod Steiger, who's still very skeptical of you, go to question one of the leading white businessmen in town. And I'll just explain in case it's confusing as our listeners hear it that as you're questioning him, the businessman slaps you, and then without missing a beat, you slap him right back.

Here's the scene.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT")

ACTOR: Let me understand this. You two came here to question me?

POITIER: Well, your attitudes, Mr. Endicott, your points of view are a matter of record.

ROD STEIGER, ACTOR: Some people -- well, let us say the people who work for Mr. Colbert might reasonably regard you as the person least likely to mourn his passing.

POITIER: We were just trying to clarify some of the evidence. Was Mr. Colbert ever in this greenhouse, say, last night about midnight?

(sound of slaps)

ACTOR: (inaudible)

POITIER: Yes.

STEIGER: You saw it.

ACTOR: Oh, I saw it.

STEIGER: Well, what are you going to do about it?

ACTOR: (inaudible)

I'll remember that. There was a time when I could have had you shot.

(END AUDIO CLIP)

GROSS: Sidney Poitier, in your new memoir, you say that's not the way the scene was originally written. Originally you didn't slap this businessman right after he slapped you. What did you do in the original scene, and why did you want to change it?

POITIER: The original scene called for the businessman to slap me, and for me to absorb it and leave. I found it reprehensible that the writers, writing for that period, would not have written it differently. And I felt that the natural emotional response to being slapped, as -- and I'm speaking not as Sidney Poitier, but I'm speaking as a Philadelphia detective -- that the natural response to a man slapping him, he's going to slap him right back.

And I elected as an actor to do that, because were I the guy from Philadelphia who was slapped, I would slap the guy right back. And I thought that that would be -- since those kinds of moments were never found in American films, from the inception of films in this country, that kind of a scene, which would be electrifying on the screen, was always either avoided, not thought of. And I insisted that if they wished my participation in the film that they would have to rewrite it to exemplify that.

They were, meaning the director, Norman Jewison, who was and is an exquisite artist, and the producer, Walter Mirisch, who is -- I mean, his record is fabulous, and we've been very good friends all these years, both of them said, Hey, that's great, let's do it that way.

So we did it, and it indeed did turn out to be a highlight moment in that film. But it also spoke not just of the two characters, it spoke of our time. It spoke of the time in America when in films, at least, we could step up to certain realities.

GROSS: In that film, you use something that you've used in a lot of your films, a very indignant stare, a stare that carries a lot of weight. (laughs) Can you talk about how you perfected that look?

POITIER: I didn't perfect that look. That look is -- I -- first of all, I don't acknowledge that I have such a look, I mean...

GROSS: Right, right.

POITIER: ... because I see myself differently than other people see me, obviously.

GROSS: Right. But is that -- is that, do you think, a look that, that came from real life, or one that you just developed for your acting roles?

POITIER: No, my acting roles are at the core of themselves a part of me. So whatever that look is, I mean, it -- I cannot manufacture such a look. It comes out of those forces that are churning internally in the individual, you know. And so I just have that look, I suppose, even when I'm thinking of things that are quite contrary to what the look might suggest. I just have that look. And I'm sorry if I've put people off with it. (laughs)

GROSS: Oh, not at all, no, I mean, it's a great look, and it's certainly the one you need in the roles that you use it in. So, no.

Sidney Poitier, in the minute that we have remaining, I'm wondering why we don't get to see you much in movies any more.

POITIER: Listen, my darling lady, I'm 73 years old. I have been working in films for 51 years. And I've made a great number of movies. And there are other areas of my life now that -- the most important currency I own is my time. And I need to spend it now with a great deal of care, you know, for obvious reasons. And I just simply don't have the time to go over ground I've covered. At least I don't want to spend the remaining time I have in this life of mine doing things that I've done before.

GROSS: Well, I...

POITIER: And...

GROSS: ... certainly wouldn't want to begrudge you that. We just miss you in the movies.

POITIER: Oh, that's very kind of you, and I thank you for that.

GROSS: Well, I thank you so much for talking with us.

POITIER: Thank you for inviting me.d

GROSS: Sidney Poitier has written a new memoir called "The Measure of a Man."

Coming up, a review of Saul Bellow's new novel.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest: Sidney Poitier

High: Actor Sidney Poitier is the leading African-American actor of his generation. He was the first, and so far, the only African-American to win the Academy Award for Best Actor, which he did in 1963 for his performance in "Lilies of the Field." His other films include, "The Defiant Ones," "A Patch of Blue," "Guess Who's Coming to Dinnger," and "To Sir, With Love." He's written a new autobiography, "The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography."

Spec: Entertainment; Movie Industry; Race Relations; Awards

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 2000 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 2000 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Sidney Poitier Discusses `The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography'

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: APRIL 18, 2000

Time: 12:00

Tran: 041802NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Maureen Corrigan Reviews `Ravelstein'

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:52

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: The friendship between the late Allan Bloom, author of the controversial 1987 book "The Closing of the American Mind," and Nobel Prize-winning novelist Saul Bellow is the subject of Bellow's new novel, called "Ravelstein." Some of Bloom's other friends think the novel should have been called "Et Tu, Brute." Book critic Maureen Corrigan has a review.

MAUREEN CORRIGAN, BOOK CRITIC: There's a literary tempest brewing over Saul Bellow's new novel, "Ravelstein," a roman a clef about his close friendship with the late conservative political philosopher Allan Bloom. Last Sunday's "New York Times" magazine ran a story about the controversy, incited by the fact that in Bellow's novel, the Bloom character is gay and dies of AIDS.

Some of Bloom's other friends are outraged by Bellow's depiction of him. They say that the cause of Bloom's death is unclear and that Bellow has betrayed his late friend by characterizing him thusly in this novel.

Yes, well, we should all be so poignantly betrayed after our deaths, preferably by Saul Bellow. Bellow has created a character in "Ravelstein" who's so lavish, so full of intellectual and consumer appetites, so sharp-eyed and demanding and funny, that after his death, about two-thirds of the way through the novel, you don't want to go on reading.

If Bellow did indeed out Allan Bloom here, well, I guess he shouldn't have. Just the way F. Scott Fitzgerald shouldn't have written about poor crazy Zelda, and Sylvia Plath shouldn't have pilloried Ted Hughes in her poems, and vice versa.

Writers great and small always cannibalize their nearest and dearest for their art. Sometimes the art is worth the unholy (inaudible), sometimes not. As far as "Ravelstein" goes, my suspicion is that if Allan Bloom knew what a compelling novel Bellow was going to create out of their friendship, his last words to Bellow would have been, "Mangia, mangia!"

The plot, such as it is, of "Ravelstein" is this. A writer named Chick who teaches at a University of Chicago-type institution has the good fortune to be taken under the wing of Ravelstein, a charismatic political philosopher on the faculty. This mentor-like relationship is a late-life boon to Chick. He's much older than Ravelstein. And as Chick walks daily past the apartment houses that surround his campus, he sees the front rooms where friends had lived, and at the sides, the windows of bedrooms where they died.

Ravelstein is one of those peculiar kind of divas that only academia breeds. He believes in an aristocracy of the intellect and also believes that his superior brainpower entitles him to regular trips to Paris and gores (ph) and comforters and custom suits from Lanvin, none of which he can afford.

So to support these champagne tastes, Chick suggests Ravelstein shape his lecture notes about culture and philosophy into a book, which, to everyone's surprise, becomes a huge best-seller, more than that, a phenomenon. But Ravelstein's triumph is tempered by the fact that he's ill, suffering from complications of HIV. Ravelstein's stated legacy to Chick is himself, Ravelstein, as the subject for a biography.

After Ravelstein's death, Chick is creatively immobilized for a few years. But then when he himself almost dies ignominiously from food poisoning he's picked up from a toxic fish, he's spurred to write. The end product is the book before us.

Obviously what gives a novel like "Ravelstein" its power is not its flat-liner narrative but the brilliance of its characterizations and the vitality of the relationship between the two men. The book has some of the famous Bellovian high-octane intellectual digressions and pointed physical and psychological descriptions. But "Ravelstein" is an old man's book. Its tone is rueful and contemplative in a way that Bellow could not or would not be before.

Chick is Socrates to Ravelstein's Plato, bound to him by awe and by a shared sophomoric sense of humor. Indeed, they're so close that Chick's third wife accuses them of being lovers. Ravelstein's conversation as set down by Chick is a glorious jumble of wit, erudition, bitchy gossip, and fancy psychological footwork.

Describing Ravelstein's power as a teacher, Chick says, "He did not court students by putting on bull session airs. There was nothing at all of the campus wild man about him. His frailties were visible. He obsessively knew what it was to be sunk by his faults or his errors. But before he went under, he will describe Plato's Cave to you. He will tell you about your soul, already thin and shrinking fast, faster, and faster."

And Ravelstein does help reveal Chick's own speckled soul to him. He prods Chick to recognize his envy, his fecklessness as a serial marrier, and the thought murders and cover-ups that drain his strength.

That's what the Allan Bloom partisans are ignoring about "Ravelstein," the novel. It's not only a debatably scandalous post-mortem portrait of Allan Bloom, but it's also the aged Saul Bellow's own courageous pre-mortem warts-and-all portrait of himself as seen through the eyes of his stern friend, Bloom.

"Ravelstein" is a slim, memorable novel about passionate friendship and loss and the disappointments in the self that you finally acknowledge, if you're brave enough, that you're going to be stuck with even to the grave.

GROSS: Maureen Corrigan teaches literature at Georgetown University. She reviewed Saul Bellow's new novel, "Ravelstein."

FRESH AIR's interviews and reviews are produced by Amy Salit, Phyllis Myers, and Naomi Person, with Monique Nazareth, Ann Marie Baldonado, and Patty Leswing, research assistance from Brendan Noonam.

I'm Terry Gross.

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest: Maureen Corrigan

High: Book critic Maureen Corrigan reviews the new novel by Saul Bellow, "Ravelstein."

Spec: Entertainment; Education; Saul Bellow; Art

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 2000 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 2000 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Maureen Corrigan Reviews `Ravelstein'

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.