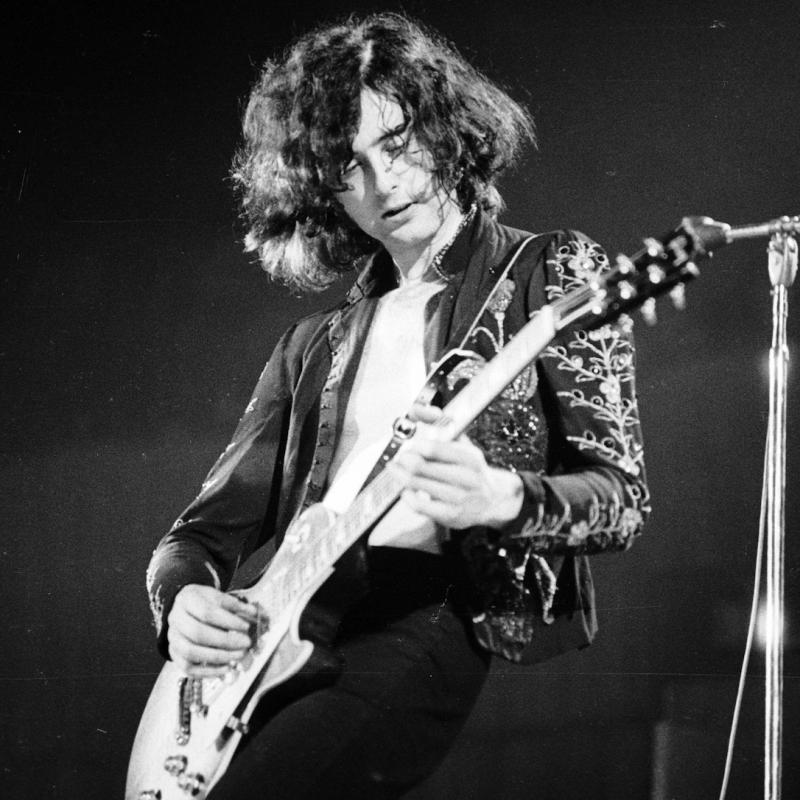

Guitar Legend Jimmy Page

He began his career with the Yardbirds in 1966. Two years later, Page formed Led Zeppelin. His powerful playing established the framework for classic tracks like "Whole Lotta Love," "Rock 'N' Roll," "Black Dog," "When The Levee Breaks" and "Achilles Last Stand." Remastered footage from several 1970s Led Zeppelin concerts has just been released on a 2-DVD set.

Guest

Contributor

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on June 2, 2017

Transcript

DATE June 2, 2003 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Marjane Satrapi discusses her memoir "Persepolis"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

You'll be surprised by what it was like for Marjane Satrapi to grow up in Iran

during and after the Islamic revolution. She tells her story in the book

"Persepolis." It's a memoir which uses the form of the comic book. Satrapi

is an artist who now lives in France. Her illustrations have been published

in newspapers and magazines.

Satrapi was born in 1969, 10 years before the revolution. Her family was

prosperous, educated and westernized. Her great-great-grandfather was the

last emperor of Persia. Her parents opposed the shah and had friends and

family members who were imprisoned by his regime. They all rejoiced when the

shah was overthrown, but their rejoicing didn't last long. Many of those

friends and family members were soon among the enemies of the new Islamic

government.

Satrapi had attended a bilingual, coed French school. Both coed and bilingual

schools were shut down after the revolution. She was 10 when the Islamic

government made it mandatory for women and girls to wear the veil.

One of the images that you've drawn for your new book describes what it was

like after all the girls and women had to wear the veil.

Ms. MARJANE SATRAPI (Illustrator/Author): Yes.

GROSS: And in the illustration, one of the kids is strangling another girl

with her chador and is saying, `Execution in the name of freedom.' Another

girl is putting the chador over her head and saying, `Ooh, I'm the monster of

darkness.' And another girl is saying, `It's too hot out.' So did you play

with the chador like that and, you know, strangle friends with it and pretend

it was a costume and act like kids do?

Ms. SATRAPI: Of course. I mean--well, yes. You know, it's not because, you

know, they push you to do something or you have to do it, because the

situation in Iran is that if you didn't wear that on your head you couldn't go

to school. And if you were a grownup and you didn't have that on your head,

you would have gone to jail. It was not the choice of people. That was like

that. So we, of course, really didn't believe in it. And as soon as we could

take it off or play with it or making it look ridiculous, we did.

And the Iranian women, they did that really during the time. That if you see

from the very beginning of the revolution until now, each year, you know, the

women, they gain about a half an inch of hair and they lost about a half an

inch of chador on their head. And today, you know, they show more hair than

they would show the piece of tissue that is covering their hair. So it is

something changing. And that means also that, you know, this thing was really

an obligation, and in no way that was the choice of Iranian people.

GROSS: During the Iran-Iraq War, Iran was bombed by Iraq. Your neighborhood

was bombed. In fact, a house on your block was hit and one of your good

friends was killed. You say in your book that you were really changed by that

and it made you fearless.

Ms. SATRAPI: Yes.

GROSS: Why did it make you fearless?

Ms. SATRAPI: When you see that your friend who is 13 years old, she can die,

then you say, `I can die also.' I mean, of course, you know, when you come

back to where you are and you see that, you know, people that you have known,

they are gone, of course, you have a very bad conscience also to say why you

should have survived and why should she die, you know, if at this moment, you

know, when the bomb exploded is a question of fate. I don't know the tenths

of a second or the tenths of an inch is nothing really, so it could be my

house, I could have died. So after that, you know, I think I accepted that I

was already dead. So from the moment that, you know, your death doesn't

matter anymore to you, then you're not scared, you know.

All these people that they died in my country to defending the country, to

defending freedom, justice in the war, whatever, I don't know in what sense my

blood would be a little bit more red than theirs, you know. My life isn't

worth more than theirs, so I'm not scared.

GROSS: So when you stop being scared, what are some of the things you started

doing that you were too afraid to do before?

Ms. SATRAPI: Well, you know, I just came out and I always say what I think.

After that, I never swallowed my words, I never hide myself, I always thought

what I think. And, you know, it doesn't matter anymore. You know, it doesn't

matter. So if, you know, people, they don't agree, if they agree, you know,

all this hypocrisy of hiding the thing to please everyone and, you know, it

just want to save my skin and everything. I did--another way to save my skin

was that I left my country in '94 definitely. But until the time I was there

until the time that I could speak and it had an effect, I spoke, and I still

do that. That was the effect of that.

GROSS: When you stopped being afraid, were there rules you started breaking

at school? Did you talk back to teachers? Did you refuse to pray when they

asked you to?

Ms. SATRAPI: Oh, yes. I even hitted the director of the school, you know,

because she wanted to take my--I had a little bracelet, Engord(ph), my mother

gave me, and she wanted to take it. And, you know, they were just robbing

things from us, that was stealing, and I say, `I don't give it.' And she

wanted to take it by force, and I beated her at the time.

GROSS: With what, your fist?

Ms. SATRAPI: Oh, no, no, no. You know, I just pushed her away. And while

she was like, you know, this wimp, so she fall down. And, you know, I didn't

push this hard neither, but she fall down. And that was a crisis, and they

threw me out of the school. And it was a whole story to find another school

and everything. But, you know, I don't regret it one second. If I had to do

it again, I would have pushed her even harder, you know.

I should just add something. All these directors of the school during these

years that I was in the school, they give the student to the guardian of the

revolution, and many kids between the age of 14 and 18, they had been killed

in the prisons because of these directors that gave the children. So, you

know, probably I would have beat her much harder than what I did.

GROSS: Who were the guardians of the revolution?

Ms. SATRAPI: Well, you know, you had the army, you had the police and then

you had another style that was this guys who were dressed like rangers and the

had big beard and, you know, they were here to make order. And, you know,

they were the law themself, you know. They would stop you because they feel

like stopping you, telling you that your scarf was not right or you spoke too

loud or why is it four people gathered together in the street? That was a

time in my country in '81, in '82 that, you know, people, they had been shoot

down in the street because they made the little demonstration, you know.

The thing that have very, very, very much changed--I am not talking about of

Iran of today, and I hope that there won't be any confusion--but at the very

beginning of the revolution it was like that.

GROSS: Now at the same time that you were rebelling against the authority

figures in your life, like your teachers, who represented the Iranian

revolution, you were also rebelling against your parents.

Ms. SATRAPI: Oh, well, that was the age, you know. That was the age. I was

like 12, 13, 14 years old. And, you know, I had to confirm myself because I

was getting tall and, you know, I was realizing that I was a human being

myself and I was not anymore just the child of my parents. So, yes.

GROSS: Yes. You write you were rebelling against your mother's dictatorship.

Ms. SATRAPI: Yes, exactly.

GROSS: What was she strict about?

Ms. SATRAPI: Well, you know, because my mother, she was a real dictator and

she still is, you know. From the second that the school, for example, they

closed, she was convinced--and I thank her so much today--she was convinced

that the only way for me to get out of this whole mess was to be very

well-educated. So, you know, the school finished every day at 2:00. Every

day she came to pick me up at 2:00. Three days per week I had French courses

between 2 and 8, so that was three days. Then one day per week I had some

German courses, because I was going to go to Austria. Then I had one day of

karate courses, even two days. And then the only day of weekend, which was

the Friday, I had painting courses. And the rest of the time when I came home

after 8:00--when we arrived it was almost 9--I had to sit and do my homework

until 11.

And my whole family was saying to my mother, `But you are mad. You're going

to kill this child.' And my mother say, `Nobody die from reading or learning.

So this child is not going to die and you're in a hectic situation. And if

tomorrow she has to leave the country, she has to know everything. The more

languages she knows, the more she knows how even to defend herself, bodily,

self-defense; if she knows how to draw, whatever I give her, that's a new

chance for her to be able to do something outside of this country.'

And she was right, because, you know, I learned, you know, not to be lazy

probably and to work hard after that.

GROSS: When it became easier a few years after the revolution for people to

leave the country for visits, your parents took a short trip to Turkey, and

they went by themselves. It was just like the parents went and you stayed

behind. And they brought you back gifts, and the gifts they brought you were

the kinds of Western things, pop culture things, that you couldn't possibly

have gotten in Iran. They got you a denim jacket. They got you an Iron

Maiden poster.

Ms. SATRAPI: Yes.

GROSS: And they had to smuggle it in then. They had to figure out creative

ways of smuggling this stuff into Iran. What did it mean to you to have that?

Ms. SATRAPI: Oh, I was the coolest person in the whole school. Imagine, I

had the big poster of Iron Maiden and a large poster of Kim Wilde. Nobody had

such things; I was the only one. And, of course, you know, I was inviting my

friends coming home watching my poster and being jealous at me. I was very,

very happy to have those, though, you know, afterwards everybody had a friend

who was in Germany or somewhere else and they were folding the posters into

letter and sending it to their friend, but I had big posters and the other

one, they had smaller posters, so it was something.

But again, you know, my book is also to show that, you know, that's not

because you're Iranian because you're listening to revolutionary song against

the West the whole day, that, you know, the pop culture...

GROSS: That's right.

Ms. SATRAPI: ...belongs to everyone. It's not because you're Iranian that

you don't know who is Iron Maiden or who is Kim Wilde. I mean, the culture in

general belongs to everyone. There is no frontier, you know. Your Edgar

Allan Poe belongs to me as much as my poet Hafez in Iran belongs to you. That

is the heritage of all the human beings.

GROSS: And now that you're older yourself, looking back, do you think that

your parents were wonderful or crazy to have almost risked their lives to

smuggle in the Iron Maiden poster and the denim jacket? I mean, if they were

discovered, not only would have the stuff have been confiscated, they probably

would have been seriously punished.

Ms. SATRAPI: Well, I think that my parents, they were wonderfully crazy; that

is, both of them. They were wonderful and they were crazy, but they wanted so

much to make me happy. And, well, they really didn't risk their life. I

mean, probably they would have, you know--I don't know--take my father's

passport for a month and, you know, just finished with the poster and these

things. You know, it was not really life-risking, but it was a risk anyway.

But, yeah. But then I was happy for one year, and I think that it worth that

for them, of course.

GROSS: My guest is Marjane Satrapi. Her new memoir about growing up in Iran

is called "Persepolis." We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Marjane Satrapi, and her new

book, "Persepolis," is a graphic novel about coming of age in Iran during the

Iranian revolution.

When you were 14, your parents sent you to a school in Austria.

Ms. SATRAPI: Yes.

GROSS: Why did they want you to leave the country? And why did they choose

Austria as the place for you to go?

Ms. SATRAPI: Well, you know, I was too much outspoken. I was just, you know,

talking all the time. And you should know that in these years they really

stopped no matter who. I mean, in the Iranian prison you had kids of 15 years

old, 16 years old, 14 years old, you had all the ages, and these kids, they

could be executed. And then it was bombed every day, and, you know, well, my

parents they had just one child. And, you know, they were always so--I don't

know. I mean, my mother always said, you know, `I will love you so much that

you should go.' And she always thought that, you know, the parents that they

keep their kids close to them, they are just a gray stick and their real love

is always to give enough possibility to your kid to go, and that was the

reasons they send me abroad.

And why Austria? Because Austria they give very easily the visa and my

mother's best friend was in Austria. And, you know, the life was not so

expensive and it was a very good French school in Austria. That's why I went

to Austria.

GROSS: Did you feel like your parents were rejecting you by sending you away?

Did you understand why they wanted to send you away?

Ms. SATRAPI: Oh, yes. At this time I understood it very well. But then when

I went in Austria and I was so misjudged because, you know, now I am the axis

of evil, but in these years, in the very early '80s, you know, I was Iranian

myself. You know, all the Iranian they were so much misjudged, you know, by

this...

GROSS: Yeah.

Ms. SATRAPI: But you know, I was escaping something, and people, they were

judging me, but by the thing that I escaped myself. And it was so hard. And

you know, when you are 14, 15, 16 you don't have any friends and, you know,

you don't have your parents and everybody judge you on everything. So I just

cut completely with my country. I just wanted so badly, you know, to

assimilate the Western culture that, you know, I just forgot who I was myself.

And I went back to Iran because of this reason, because I was just too

finished, too tired for that. And that is just much afterwards that I

understood that to assimilate another culture, first of all, I have to assume

my own culture and to assume who I am myself, and then I can open myself to

the other ones. And that's made me go back, and this time I was kind of angry

to my parents, you know, because I thought that it was a rejection. But it

didn't last very long, you know.

GROSS: You returned to Iran when you were 18...

Ms. SATRAPI: Yes.

GROSS: ...intending to go to college there. Did you stay that long?

Ms. SATRAPI: Oh, yes. I stayed for six years in Iran; five and a half years

like that. I made master in visual communication. You know, I got married, I

divorced, I worked; I did all sorts of things. And that is only after that

that I came back in '94 to France. But this year that I had in Iran, first of

all, I was so happy to be in Iran, and I can tell you I never partied as much

as I did there, because since there, you know, party was forbidden and

everything was forbidden, we, the students, you know, we were just together

almost every night making a party every night, because, first of all, it was

forbidden and then we lived in such a repressive society that the only way to

have a balance in our personal life was to have a big freedom in our personal

life.

GROSS: Where did you hold the secret parties? And what were the parties

like?

Ms. SATRAPI: Oh, like the parties that you have here with more sophisticated

people because, again, you know, whatever is forbidden you make it even more.

For example, you know, now United States, for example, is forbidden to smoke.

I smoke three times as much as I do in France where I have the right to smoke.

So that's the nature of the human being. So it was hold in the apartments,

for example, in my apartment and everybody came and you had this Rolling Stone

music and you had Deep Purple and you had--I don't know--whatever you can

imagine, you know, from--I don't know; whatever. And, well, we were drinking

alcohol and dancing and shouting and all of that, but at the same time we're

risking to be arrested and we had been arrested one billion time. I mean, how

many times haven't I been arrested because of the fact that I was in a mixed

party with my friends? And then they came and, you know, they stopped us.

And we were one night in the jail. And the day after, the parents--they had

to come, they had to pay. We had to sign a paper saying we would never start

to make party again, but we did it; you know, life continues.

GROSS: Would your neighbors call the police?

Ms. SATRAPI: Well, once in a while, unfortunately, they would, the neighbors.

But also in my neighborhood we didn't have any neighbors seeing us, but there

was just, you know, the cars of this guardian of the revolution just cross

around the city and they see, you know, one window light and with people, and,

you know, then they--you know, they just watch and they ring on the door to

check. And once in a while there's a party; yes. But, of course, you always

have also bad neighbors, you know; human being is pervert.

GROSS: Are your parents still living in Iran?

Ms. SATRAPI: Yes. Yes, they do.

GROSS: And what is their life like now? Are they living with fewer

restrictions than they used to?

Ms. SATRAPI: Oh, no. You know, the situation in Iran has very, very much

changed, you know, in the two, three last years. For the first time in the

history of Iran, we had a free press, although, you know, they would close a

magazine one day; the day after the same magazine come out under another name,

but it continues. You know, there's still a few journalists in the prisons,

but they are not executed. They are in the prison, which is--I mean, between

being in prison and being executed, it's better to be in prison, so that is an

evolution.

And some of the situation has very much changed. You know, you have much more

freedom. And that's a real change in Iran. The situation is absolutely not

like it was before. It doesn't mean that, you know, it's the best country in

the whole world and, you know, we have so much freedom we don't know what to

do with, but it is absolutely not the way they show it to us and certainly not

like it was in the beginning of the '80s.

GROSS: You're still an Iranian citizen, even though you live in France.

Ms. SATRAPI: Yeah.

GROSS: Was it difficult to get a visa to come to the United States?

Ms. SATRAPI: Yes. I had to stay two months, and then I have kept for one and

a half hour in the airport. Yes, it was very difficult.

GROSS: So you were kept for one and a half hours at the US airport?

Ms. SATRAPI: Yes. Yes. And, you know, I mean the security things is

something, but, you know, it's a limit not to pass and, you know, you cannot

talk to people, look down at them just, you know, because of an Iranian

passport. Unfortunately, I couldn't answer, because I had to have my stamp to

be able to come in. But...

GROSS: Did you show them your book and say, `This is who I am'?

Ms. SATRAPI: Yes. And I showed them even, you know, the invitation from my

editor, etc., then I had to swear on God that I was not lying, fingerprints,

you know, photo from the side, from the back, whatever. So it was difficult;

yes.

GROSS: Were they impressed by the book and the letter from the editor?

Ms. SATRAPI: They didn't look at it even.

GROSS: OK.

Ms. SATRAPI: All they were interested in was my passport and so, you know, my

evil side.

GROSS: Well, I want to thank you so much for talking with us.

Ms. SATRAPI: Thank you very much.

GROSS: Marjane Satrapi's new memoir is called "Persepolis: The Story of a

Childhood."

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

(Announcements)

(Soundbite of music)

LED ZEPPELIN: (Singing) Way down inside, what more do you need?

GROSS: Coming up, heavy metal guitar god Jimmy Page. There's a new Led

Zeppelin DVD set. And book critic Maureen Corrigan reviews two new debut

collections of stories.

(Soundbite of music)

LED ZEPPELIN: (Singing) Ah-ah-ah-ah. Ah-ah-ah-ah. Oh. Shake for me, girl.

I want to be your back-door man. Hey. Oh. Hey. Oh. Hey. Oh. Whoa.

Oh. Ooh, my--my. Keep it cooling, baby. Keep it cooling, baby. Keep it

cooling, baby. Wha-wha-ha.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: Two short-story collections, "The Winter Without Milk" by

Jane Avrich and "The Laws of Evening" by Mary Yukari Waters

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Two new short-story collections take readers from war-torn Japan to a vision

of Manhattan's Upper West Side filled with witches and banshees. Book critic

Maureen Corrigan has a review.

MAUREEN CORRIGAN reporting:

Every semester, I warn my writing students against relying on the old

comparison-contrast essay format. You know what I mean: Jay Gatsby and

Captain Ahab, alike but different. It's such a predictable way of organizing

material, so I hope none of those ex-students are listening now as I say that

Mary Yukari Waters and Jane Avrich are two young women, both short-story

writers with exceptional debut collections that are, well, alike but

different. I surrender.

Sometimes the truth lurks in cliches, which is what I feared Mary Yukari

Waters' collection, "The Laws of Evening," might turn out to be full of before

I read it. Waters was born in Japan and moved to America when she was nine.

She's half Japanese and half Irish-American. The eleven stories in her

collection focus on women's lives in a chaotic Japan during and after World

War II. I initially wondered if the fact that Waters had no firsthand

knowledge of wartime rationing and bombings and life in an occupied country

might make her go for stale observations, borrowed from old war movies. Not

to worry. Waters' empathic imagination is so vivid she makes her reader feel

like a silent witness to the small acts of cruelty and surrender that the

history books can't record.

Many of the women in these stories are remembering the war in the tranquility

of their old age, which gives "The Laws of Evening" a melancholy tone,

sometimes leavened with gallows humor. In a story called "Since My House

Burned Down," an old woman, displaced by her tomato-sauce-wielding

Americanized daughter-in-law, almost fondly recalls resorting to eating raw

chicken sushi during the war.

In "Shibu-Sa,"(ph) one of the most moving stories here, the atmosphere of

grief is unalloyed. In a prologue to the tale, the narrator recalls how, as a

girl, she excelled in the ancient rituals of etiquette. Her elders told her,

however, that her graceful bows lacked something, something they called

`shibu-sa,' which roughly translates into `sorrowful sentience.' Later, our

narrator marries and moves to Japanese-occupied China with her young husband,

a business executive. They eventually have a son. In 1941, they return to

their home town in Japan. One day, when the woman is standing on a rationing

line across town, bombs fall on their neighborhood, killing her family.

Remembering that loss and the humiliation of a postwar encounter with one of

her husband's former colleagues turned fish peddler, the narrator realizes

that she, and so many others in her generation, have attained shibu-sa,

sorrowful sentience, which is also what graces the stories in Waters'

collection.

The 15 tales in Jane Avrich's debut, "The Winter Without Milk," are also

mindful, especially of telling details, but wickedly so. Listen, for

instance, to this description from the story "Life In Dearth," where the

narrator reminisces about her seaside childhood among economic and emotional

tightwads.

`My aunt feared charity as much as my uncle. She would not accept so much as

a spoonful of sugar, even if a neighbor had barrels to spare. Whatever was

missing from a recipe, she'd supplement with sand. Her cakes and pies were

granular and lump hard. Her puddings smelled of the sea. At Christmastime,

her gingerbread cookies had pebble noses and seaweed hair. Random bites could

chip your teeth, but you had to gag and bear it.'

Without a smidgen of feyness, Avrich stirs lots of literary allusions into

here distinctive stories, some of which read like wry nightmares. Take

"Literary Lonely Hearts," which describes the travails of a man who signs on

with a dating service that matches men with their ideal fictional heroines.

His regrettably turns out to be the undependable Hester Prynn. Lady Macbeth

and Kathy Ernshaw(ph) also make direct appearances here, while in the story

called "La Belle Dame sans Merci," a young woman named Matilda(ph) attempts to

seduce her neighbor, a married man with an ill wife, by slipping lines from

Keats' spookier poetry under his door. Where the stories in "The Laws of

Evening" make their impression on a reader through the gentle inexorable

buildup of sadness, those in "The Winter Without Milk" are hectic, dramatic

and spiteful. Both collections live up to the promise of their elegantly odd

titles.

GROSS: Maureen Corrigan teaches literature at Georgetown University. She

reviewed "The Laws of Evening" by Mary Yukari Waters and "The Winter Without

Milk" by Jane Avrich.

Coming up, Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Jimmy Page discusses his musical career as co-founder

and lead guitarist of Led Zeppelin

TERRY GROSS, host:

In the late '60s, Led Zeppelin became the prototype of the heavy metal band.

As "The Rolling Stone History of Rock & Roll" says, the band changed the

landscape against which rock 'n' roll was played, and so the basic formula for

heavy metal was codified, blues chords plus high-pitched male tenor vocals

singing lyrics that ideally combined mysticism, sexism and hostility.

(Soundbite of music)

LED ZEPPELIN: (Singing) Hey, girl, stop what you're doing. Hey, girl, you'll

drive me to ruin. I don't know what it is I like about you, but I like it a

lot. Won't you let me hold you, let feel your loving charms. Communication

breakdown. It's always the same. I'm having a nervous breakdown. Drive me

insane!

GROSS: Led Zeppelin broke up in the early '80s. Now Led Zeppelin has a new

two-DVD set, which features excerpts of four concerts as well as interviews

and TV clips. A review in Rolling Stone described the set as the Holy Grail

of heavy metal. Jimmy Page co-founded the band and became one of rock's

guitar gods. Before Led Zeppelin, he played with The Yardbirds. He joined

the band shortly before Jeff Beck left.

Last week, while I was away, guest host Barbara Bogaev recorded an interview

with Jimmy Page.

BARBARA BOGAEV (Host): Before you joined up with The Yardbirds and before the

whole Led Zeppelin thing happened, you were an established session player in

London. You played with The Kinks, with the Stones, with Donovan, with Burt

Bacharach. What did you learn from session work that you used later in both

playing and producing in Led Zeppelin?

Mr. JIMMY PAGE (Founder, Led Zeppelin): Well, I've got to tell you that what

it was really was an apprenticeship, but the reality of it was that the

session musicians were actually, in London, a very, very closed shop. It was,

you know, the creme de la creme really. However, they needed somebody who

really knew exactly what was going on with all the music of the day and the

source music of it and everything, and also somebody who could come up with

his own ideas. And I played on a record anyway that got in the lower end of

the top 20. And all of a sudden, behind these closed doors of the creme de la

creme, there was like, `Who's that guitarist on that record?' And I was

brought in just initially to play exactly what I--they said, `Just play what

you want.' They gave me the chord charts, and that was really fun. You could

imagine that, you know. It was good.

And then bit by bit, they give me, like, a few dots, you know, looked like

crows on telephone cables, you know. And I realized that I'd have to start

reading music. So I started to read music. I was doing all these--I'd be

doing three sessions a day, five sessions a week, so that's 15 sessions.

Sometimes I could be playing with a group. Sometimes I could be playing

with--could be doing film music. It could be a folk session. And, you know,

the thing is that because I listened to all this sort of music, I was able to

fit all these different roles. And they probably thought that was really

quite cool. And, you know, after a while, my ability to read music improved

and improved and improved. So really, I just became quite an accepted member

within this very privileged society, you know.

BOGAEV: Was it the session work and the time that you spent in the studios

that got you interested in the technology and producing records?

Mr. PAGE: Oh, yeah, yeah. This apprenticeship that became part of the

reading of music, it also became part of how things were recorded. You know,

I started to learn microphone placements and things like that, what did and

what didn't work. I certainly knew what did and didn't work with drummers,

because they put drummers in these little sound booths that had no sound

deflection at all, and the drums would just sound awful. And the reality of

it is that a drum is an acoustic instrument. It relies on, you know, having a

bright room and a live room or at least a booth or whatever. And so bit by

bit, I was learning really how not to record.

BOGAEV: I'm thinking that Led Zeppelin is one of the first bands to really

have an ambient--a band that recorded its ambient sound. I mean it...

Mr. PAGE: Yeah.

BOGAEV: ...sounded as if someone was playing drums at a party when you

listened to Led Zeppelin records. Was that the sound that you were going for?

Mr. PAGE: Well, certainly so that the drums could breathe. One of the

marvelous things about John Bonham, which made things very easy, was the fact

that he really knew how to tune his drums. And I'll tell you what, that's

pretty rare in drummers those days. He really knew how to make the instrument

sing, and because of that, he got so much volume out of it just by playing

with his wrists, you know, just an astonishing technique that was sort of

pretty holistic if you see what I mean. But, yeah, as far as the drums went,

right from the first recording, it was given a lot of space so you could get

the ambience of it. As far as my end of it went, there was always great

attention paid to where the drums were going to be and whether you could hear

all the harmonics from them. And also the one that, for instance, "When The

Levee Breaks" was something where we were playing in one room in a house with

a recording truck, and a drum kit was duly set up in the main hallway, which

is a three-story hall with a staircase going up around the inside of it in a

big house, you know. And when John Bonham went out to play the kit in the

hall, I went, `Oh, wait a minute, we got to do this.' And curiously enough,

that's just a stereo mike that's up the stairs on the second floor of this

building, and that was his natural balance.

BOGAEV: Well, let's listen to that. This is "When The Levee Breaks." Jimmy

Page is my guest, who's co-founder and lead guitarist for Led Zeppelin.

(Soundbite of music)

LED ZEPPELIN: (Singing) If it keeps on raining, levee's going to break. If

it keeps on raining, levee's going to break. When the levee breaks, have no

place to stand.

BOGAEV: And we're listening to "When The Levee Breaks," Led Zeppelin. My

guest is Jimmy Page, the co-founder and lead guitarist for the band.

Now that term `heavy metal' didn't exist before Led Zeppelin. When you first

heard the term `heavy metal,' what did it mean to you, and is that what you

thought you were playing? I mean, the band started out as a blues-rock band

and had a slow evolution.

Mr. PAGE: Yeah, I'm not really sure where we got a tag of that, but there's

no denying, I mean, the fact that the elements of what became known as heavy

metal is definitely there within Led Zeppelin. But the reality of it is that

it's riff music, and riff music goes back to the electric blues of the '50s,

you know, and what was going on down there in Chicago. And that's it, you

know. It's curious. Actually, it's said that it's William Burroughs who

first termed in it the book, and the Heavy Metal Kid is one of the characters,

you know. When he did an article in the '70s with me for a magazine called

Crawdaddy!, and at that time, I was really honored that he'd been to Zeppelin

concerts, and he'd been to a few. I was really quite surprised, 'cause I

didn't know. But he'd asked to interview me. And at that time, he said,

`You've got to go to Morocco, because that's where you're going to'--he said,

`What you're doing is trance music.' Well, I knew that. I knew it was trance

music without any doubt. But he said, `You've got to go to Morocco, because

that's where you're going to hear, you know, riff music.' But you know, it

was a good call, and I went there, and I understood exactly, you know, why

he'd asked me to go there.

BOGAEV: When you say you knew it was trance music, was that the effect you

were going for, or is that what you felt when you performed it?

Mr. PAGE: No, that's just exactly what happened with it.

BOGAEV: Uh-huh.

Mr. PAGE: It was trance music.

BOGAEV: In terms of the relationship between you on the stage and the

audience?

Mr. PAGE: In all of it, yeah, within what was being played and what would

emanate from it, you know, in every way. But, yeah, it definitely was trance

music. There's no doubt about that.

BOGAEV: Now "Stairway to Heaven." "Stairway to Heaven" you wrote in 1970.

What was going on in the band at the time that you wrote that song?

Mr. PAGE: Well, we were recording at Headley Grange, which was a house, where

we were staying. But we had a recording truck, and it was a really, really

good working environment, you know. And I had these guitar pieces that I

wanted to put together. I had a whole idea of a piece of music that I really

wanted to try and present to everybody and try and come to terms. It was a

bit difficult really, because it started on acoustic. And as you know, it

goes through the electric parts. But we had various run-throughs where I was

playing the acoustic guitar, and then jumping over and picking up the electric

guitar. And Robert was sitting in the corridor, leaning against the wall.

And as I was routining the rest of the band with this idea and this piece, he

was just writing. And all of a sudden, he got up, and he started singing

along with, like, another run-through. And he must have had 80 percent of the

words there. And why I'm saying that story is I just want to let you know

just how inspired we all were at that point in time. We were inspired by each

other, you know.

BOGAEV: Now your guitar part. Of course, the introduction is one of the most

famous acoustic guitar bits in rock. That and maybe "Free Bird" is what all

aspiring guitarists play. And I think every guitar store in the world has a

sign requesting that you please not play "Stairway to Heaven" when trying out

the instrument.

Mr. PAGE: Yeah, but would they permit me to do it if I went in there?

BOGAEV: Did you ever ask? I was going...

Mr. PAGE: No, no. Why not? "Stairway" denied.

BOGAEV: Was the lead-in something that you had fiddled around with on your

own, and were you looking for...

Mr. PAGE: Was what? I'm sorry.

BOGAEV: Was the lead-in something that you had fiddled around with on your

own when you picked up your...

Mr. PAGE: Oh, no. That was part of one of the sections that I had, you know.

Yeah, as I said, it was a number of sections I wanted to join together. And,

yeah, oh, I had that well and truly before I went into Headley Grange, yeah.

And the whole thing about "Stairway" was that it was something which, going

back to those studio days, for me and John Paul Jones, the one thing you

didn't do was speed up. Because if you sped up, you wouldn't be singing

again, you know. Everything had to be right on the meter all the way through.

And I really wanted to write something which did speed up and took the emotion

and the adrenaline with it and would reach a sort of crescendo, you know. And

that was the idea of it. And that's why it was a bit tricky to sort of get

together in its early stages. But, no, I had these sections, and I knew what

order they were going to go in, but it was just a matter of getting everybody

to feel comfortable with each sort of gear shift that was going to be coming.

BOGAEV: Well, we've got to hear it now. This is Jimmy Page, Led Zeppelin, is

my guest. Here's "Stairway to Heaven."

(Soundbite of music)

LED ZEPPELIN: (Singing) There's a lady who's sure all that glitters is gold,

and she's buying the stairway to heaven. When she gets there, she knows, if

the stores are all closed, with a word, she can get what she came for. Ooh,

ooh, and she's buying the stairway to heaven. There's a sign on the wall, but

she wants to be sure, 'cause you know sometimes words have two meanings.

BOGAEV: "Stairway to Heaven," Led Zeppelin. I'm speaking with Jimmy Page,

the co-founder and former lead guitarist for the band.

I think virtually everyone in my generation at least, at one time or another,

made out to "Stairway to Heaven" in a rec room somewhere, or made out while

someone played "Stairway to Heaven" on a guitar on a beach somewhere.

Mr. PAGE: Oh, please, there wasn't a guitarist playing "Stairway to Heaven"

when you were making out. I'm really relieved at that.

BOGAEV: I'm curious what stories fans tell you about that song, what it means

to them, what memories they have.

Mr. PAGE: Well, you know, the wonderful thing about "Stairway" is the fact

that just about everybody's got their own individual interpretation to it and

actually what it meant to them at their point of life. And that's what's so

great about it. Over the passage of years, you know, people come to me with

all manner of sort of stories about, you know, how it meant or what it meant

to them at certain points of their lives, how it actually got them through

some really tragic circumstances or to the other point where--you know, 'cause

it's an extremely positive song, you know. It's such a positive energy in it.

And, yeah, people have got married to that.

GROSS: We're listening to an interview that Jimmy Page recorded with Barbara

Bogaev for our show. There's a new Led Zeppelin DVD set. We'll hear more of

the interview after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Let's get back to the interview that FRESH AIR guest host Barbara

Bogaev recorded with guitarist Jimmy Page. There's a new Led Zeppelin two-DVD

set.

BOGAEV: When you were a kid first learning guitar, did you have a song like

"Stairway to Heaven," the song that everyone played, and a lot of people

played it to impress girls at parties?

Mr. PAGE: I don't know. I didn't used to go to parties.

BOGAEV: Did you listen to music with friends, or was music something private?

Mr. PAGE: Playing guitar was, because to be honest with you, when I grew up,

there weren't many guitarists, you know. There weren't any. And there was one

other guitarist in my school who actually showed me the first chords that I

learned, and I went on from there. So it was something I taught myself the

guitar from listening to records. So, yeah, obviously, it was a very personal

thing. You couldn't sort of bring your friends around and have a dance party

and suddenly start playing guitar and say, `Well, hang on. I want to move

that back and listen to that solo again,' you know, so it's just the way that

it was.

BOGAEV: Who did you listen to? What music did you listen to?

Mr. PAGE: I listened to the early rock of the `50s, you know, sort of Elvis,

which is such an important inroad, really, from the musicians that were in all

of that, you know, and the bands that were relative to that. I mean, I was

gobbling it all up. I was trying to take on board as much as I could, Johnny

Burnette Rock 'n' Roll Trio, Jean Vincent, you know, all of these things. And

bit by bit, one began to access the blues, because they were playing 12-bar

blues, and then I became open to listening to sort of, you know, Muddy Waters

and Elmore James and Robert Johnson. I guess it was almost similar to doing a

university course, you know. You were just learning and learning and

learning, and at the end, you came out with your paper. And I guess my paper

was Led Zeppelin.

BOGAEV: Led Zeppelin really hit it big on the first and second US tour, 1968

and 1969. And somewhere in there, the band became a full-fledged happening

with the whole groupie scene and Rolls-Royces driven into swimming pools and

girls camped out in hotel corridors. Some very intense groupies, I think,

Squeaky Fromme, I think, turned up at some point in there, the girl who

attempted to assassinate Gerald Ford. So...

Mr. PAGE: That must have been one of Robert's friends. It wasn't one of

mine.

BOGAEV: Yeah. At the time, what was your attitude towards the whole scene?

Mr. PAGE: What, for me, is the most important thing, and always was, no

matter what, that's the whole reason of going up on a stage and never knowing

exactly what was going to happen from the moment you walked on to the moment

you walked off musically. So much importance seems to be put on what happened

to Led Zeppelin when they weren't on that stage. And I find it quite amusing.

But I just want to explain. You go up on stage and play for three hours and a

half, and you know, you're not just turning on an adrenaline tap here, you got

floodgates going. And the thing is that when you come off stage, the one

thing you don't do is go home and have a cup of cocoa and go to bed. And we

would go to clubs after that, and for us, clubs, the energy of the club was

actually coming down from the intensity of the show, so that's what I'm going

to say, and have a good time, Barbara.

BOGAEV: You toured with The Black Crowes a few years ago. How did that

touring experience compare to your memories of touring?

Mr. PAGE: Well, I had a wonderful time with The Black Crowes. It was just a

fantastic party, to be honest with you. It was great to play their music. I

really loved it. And actually doing the Zeppelin music with them was quite an

experience, because, for example, we did "Ten Years Gone," and all of a

sudden, I heard all the guitar parts that I'd never heard apart from one

record. I mean, we could never do all those guitar parts with just the one

guitar with Led Zeppelin. And it was fantastic. I was having such a great

time. And Chris Robinson, well, you know, I can't say enough about how

brilliantly he sang. And I can't say enough about what a good band it was,

too. It was a band that I always really, really, really liked. And I'm right

here in New York now, and we played the Roseland Ballroom here, and it was

just scary. It was fantastic. So, yeah, I had a great time with them, and I

hope they had a great time with me.

BOGAEV: Jimmy Page, thanks very much for talking today.

Mr. PAGE: Thanks very much. OK, bye.

GROSS: Guitarist Jimmy Page with FRESH AIR guest host Barbara Bogaev. Their

interview was recorded last week while I was away. Led Zeppelin has a new

two-DVD set of concerts, interviews and TV appearances.

(Soundbite of music)

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

(Soundbite of music)

LED ZEPPELIN: (Singing) The leaves are falling all around. Time I was on my

way. Thanks to you, I'm much obliged for such a pleasant stay. But now it's

time for me to go. The autumn moon lights my way. For now I smell the rain,

and with it pain, and it's heading my way. Oh, sometimes I grow so tired, but

I know I've got one thing I got to do. Ramble on. And now's the time, and

the time is now, to sing my song. I'm goin' 'round the world. I got to find

my girl on my way. I've been this way...

(Announcements)

Announcer: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

GROSS: On the next FRESH AIR, suicide bombers, the men who train them, the

mothers who outlive them, and the ways in which they are celebrated after

death. We talk with journalist Joyce Davis about her new book, "Martyrs:

Innocence, Vengeance and Despair in the Middle East." I'm Terry Gross. Join

us for the next FRESH AIR.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.