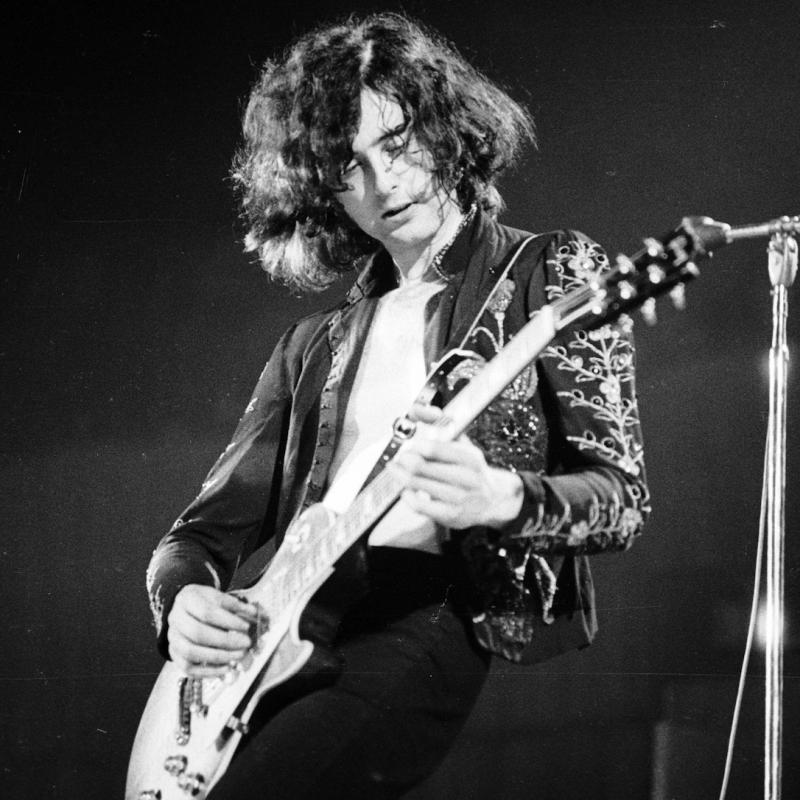

Judas Priest Lead Singer Rob Halford

Judas Priest has a new album out, Angel of Retribution, and is on tour this summer. Originally from Birmingham, England, Judas Priest pioneered the heavy metal sound in the 1970s and '80s. Lead singer Halford left the band in 1991, citing internal tension, and in 1998, he disclosed that he is gay during an interview on MTV. Nicknamed the "Metal God," Halford returned to Judas Priest in 2003. The band — which takes its name from the Bob Dylan song "The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest" — is best known for songs such as "Breaking the Law," "Hell Bent for Leather" and "Livin' After Midnight."

Other segments from the episode on June 21, 2005

Transcript

DATE June 21, 2005 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Rob Halford discusses his heavy metal band Judas Priest

and new CD, "Angel of Retribution"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

As the lead singer of the British heavy metal band Judas Priest, my guest Rob

Halford became famous for his powerful voice, the leather studs and handcuffs

he wore on stage and the way he often made his entrance on his motorcycle.

Judas Priest is one of the originators of heavy metal and one of the most

theatrical and successful bands in the genre. Famous for such songs as "Hell

Bent for Leather," "Breaking the Law," "Ram It Down" and "You've Got Another

Thing Comin'," Priest was a band that scared some parents. In 1990, a lawsuit

claimed one of their records convinced two teen-age boys to commit suicide.

The judge ruled in favor of the band.

Rob Halford started singing with Priest back in 1971. He left the band in '92

and later surprised his fans by coming out. Being gay sure didn't fit the

stereotype of the heavy metal god. Two years ago Halford returned to Judas

Priest. Now the band has a new CD called "Judas Rising," and it's the first

one to feature Halford since 1990. The flip side of the CD is a DVD.

Let's start with a track from the CD "Hellrider."

(Soundbite of "Hellrider")

Mr. ROB HALFORD (Judas Priest): (Singing) Here they come, these gods of

steel, megatron devouring what's concealed. Speed of death, crossfired they

stare, final breath from vaporizing glares. Raised to man oppressed, sign

of persecution. Hellrider roars on through the night. Hellrider raised for

the fight. All incensed to overthrow...

GROSS: Rob Halford, welcome to FRESH AIR.

Mr. HALFORD: Thank you for inviting me.

GROSS: Pleasure to have you here.

Mr. HALFORD: Pleasure to be with you. Thank you.

GROSS: How did the band decide to get back together, and how did you decide

to get back together with them?--because you'd already left the band years

before.

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah. You know, this is another movie in the making, isn't it,

really?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. HALFORD: We had "Rock Star."

GROSS: Right.

Mr. HALFORD: Should be "Return of the Rock Star." You know, it's--bands are

strange animals, and there are a lot of emotions and a lot of stories attached

to the wonderful life of Judas Priest over the last 30 years. We've been

seeing each other individually over the years, but this was the first time

we'd actually been together in a, quote-unquote, "band meeting," which was at

my house in England. And we were there to discuss the first-ever box set by

Sony, which was the "Metalology" box set. And I think the emotions of that

box set, looking at all the incredible things that we'd done together

musically, just came to the top. And the final question at the end of that

meeting was, `Well, are we going to reunite? Are we even going to consider

reuniting?' And we just looked each other in the eye and said, `We got to go

for it, you know.'

GROSS: So what's it like, more than 30 years after you started in Judas

Priest, to be, you know, putting on the costumes again, the leather and, you

know, the studs and the collars and all the stuff...

Mr. HALFORD: Well...

GROSS: ...and then to be singing these kind of...

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah.

GROSS: ...anthems that were like teen-age anthems of defiance...

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah.

GROSS: ...for your audience?

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah.

GROSS: But so many people who were your fans early on are probably in

positions of authority themselves now. I bet there's a lot of...

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Really, I bet there's a lot of, like, cops...

Mr. HALFORD: That's true. No, that's very cool.

GROSS: ...who were your fans and teachers who were your fans and...

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah. Well, the--you know...

GROSS: ...parents who were your fans.

Mr. HALFORD: Yes. Yup. Absolutely. And you've just named three parts of

society which attend frequently Judas Priest shows. I have friends...

GROSS: And used to be terrified of you, right? Like, this was a bad era...

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah. Well, maybe so. Exactly.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. HALFORD: You wouldn't believe the amount of law enforcement that loved

Judas Priest, especially here in New York City. And here we are, a band that

wrote this called "Breaking the Law"...

GROSS: Right. Exactly (laughs).

Mr. HALFORD: ...you know, which is quite remarkable. But I think beyond

that, there's this incredible bond that is maintained with our fan base

internationally.

GROSS: One of the things that has changed is that you're out now. And this

is the first time you're performing with Judas Priest since you've been out.

And do you think that changes anything for you and the band or changes the way

your audience sees you?

Mr. HALFORD: Well, I think it destroys the myths of, you know, the so-called

intolerance and homophobia that was supposedly existing in heavy metal.

Having said that, I think that if I'd have done this earlier in the '70s or

the '80s, things may have been a bit more difficult. But that's kind of a

debatable question because we never really confronted the issue at that time.

I wanted to do it for myself, like any gay man or lesbian woman and anyone

that wants to, you know, bring this forward. And my proclamation is it's what

you're entitled to; it's your own right, so to speak. But I was always

protective of Judas Priest. I always felt that if I'd have done this any

earlier or had I've done it in different circumstances, the fallout would have

damaged the band. And I would never do anything to hurt the band or its

reputation or its following.

So I think that, you know, the timing was right. I was at MTV studios. It

was very much an unplanned moment of speech on my part. I heard the guy's

clipboard drop to the floor when I mentioned that, you know, yada, yada, yada,

`speaking as a gay man.' But that was it for me. And, you know, the word

went out, and there was a little bit of a firestorm for a time, not in a

negative way, just the way that news and information travels at the speed of

light these days. And so it was. It settled down. And just for me

personally, it was a great moment of release.

GROSS: You know what I love about the fact that you did come out is I think

for so many teen-age boys, heavy metal is not only about the music. It's

about, you know, these fantasies of, like, orgies with women, you know, and

having all the women...

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: ...and how you're going to treat the women...

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah, the sex and drugs and rock 'n' roll thing. Yeah.

GROSS: Yeah. And, you know, if nothing else, it's like your coming out

really complicates all of the cliches about, you know, the sex part of the

sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll.

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah.

GROSS: And it takes it out of this kind of simplistic, sometimes misogynistic

fantasy that I think teen-age boys have.

Mr. HALFORD: Exactly. Well, without laboring on one element here, just the

teen-age boy element--because, of course, the thing about Judas Priest's music

is that we're not the same as every other heavy metal band. I think we've

created our own niche, our own particular stamp, identity, trademark, whatever

you want to call it. We've never--the closest this band has been to a party

band is "Livin' After Midnight," you know, and that was one song that covered

that topic. But, again, if you look at the broad catalog of this band's

material, some hundreds and hundreds of songs over a three-decade span, I

think that that's just, really, one small focus of area...

GROSS: Well, a lot of your songs have this kind of, like, mythic quality to

it.

Mr. HALFORD: Yes, they do.

GROSS: Like, even the song "Hellrider," which we opened with...

Mr. HALFORD: Yes.

GROSS: ...from the new CD--I'm just going to--forgive me as I read some of

the lyrics. I'm not...

Mr. HALFORD: Please do. Please do.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. HALFORD: Go ahead.

GROSS: OK. `Hellrider, hellrider, you slaught them all extinguished, wrath

of doom in killing fields, they consume for valiants never yield.'

Mr. HALFORD: Yes.

GROSS: `Triumph to the gods vanquished...'

Mr. HALFORD: Yes.

GROSS: `...of enslavers.'

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. HALFORD: Absolutely. Well, there you go.

GROSS: It's like overblown, mythic language.

Mr. HALFORD: Isn't it wonderful? It's wonderful. But you see what the

overriding story is there? The overriding story is of optimism. And the

overriding story is of defeating anything that stands in your way, that

prevents you from achieving your goals or your dreams. A lot of the lyrics

that I write for Priest--and I'm the primary lyricist in the band--come from

this streak that I have inside of me, which has always been one of

determination and overcoming the odds. And things...

GROSS: But this has really, like, archaic language.

Mr. HALFORD: Oh, it does.

GROSS: You `slaught them all.'

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. HALFORD: Ah, but that's because I love to--I love the English language.

My favorite book is a thesaurus, you know. I'm constantly looking to find

words and language that some bands would maybe hesitate to use or they're not

able to because of the arena that they work in.

GROSS: Though I have to say, like, the Judas Priest songs, particularly

something like the classic ones, like, real hits, like "Breaking the Law,"

they have...

Mr. HALFORD: Yes.

GROSS: ...so many pop hooks within them. OK, sure, it's like it's heavy

metal, but there's so much pop within it. And I think particularly listening

a couple of decades later, you can really hear the pop elements in it, you can

really hear the hook.

Mr. HALFORD: Melody is everything, isn't it? It doesn't matter whether it's

da-da-da-dah, you know, or whatever. I mean, it's just all about the hook,

it's all about the melody. And we were born and raised in a time in the UK, I

guess in our formative years of music, around the '60s, which was full of

Beatles, and we were all big Beatles fans. And there is your absolute primary

example of great melody and great formula in song structure. And I think in

our way we actually went very close to that with the "British Steel" album,

which is where "Breaking the Law" came from and "Livin' After Midnight." So

we kind of fine-tuned ourselves through those writing sessions and were able

to make very precise, concise pieces of material that were just full of melody

and memorable hooks.

GROSS: Well, why don't hear "Breaking the Law"? And this one of the Judas

Priest classics. And my guest is singer Rob Halford, who also is one of the

songwriters--this is one of yours. So here's "Breaking the Law."

(Soundbite of "Breaking the Law")

Mr. HALFORD: (Singing) There I was completely wasting and out of work and

down. All excited, so frustrating, had to drift from town to town, feeling

as though nobody cares if I live or die. So I might as well be dead, but the

future's in my way. Breaking the law, the breaking the law. Breaking the

law, breaking the law. Breaking the law, breaking the law. Breaking the law,

breaking the law. So much for the golden future; I can't even start. I've

had every promise broken, anger in my heart. You don't know what it's like.

You don't have a clue. If you did, you'd find yourself doing the same thing,

too. Breaking the law, breaking the law.

GROSS: That's Judas Priest. My guest is the band's lead singer, Rob Halford.

They have a new CD called "Angel of Retribution." We'll talk more after a

break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is Rob Halford, the lead singer of the heavy metal band

"Judas Priest." They have a new CD called "Angel of Retribution."

Now there's the Judas Priest sound; there's also the Judas Priest look. And,

I mean, you were one of the creators of that look--of wearing, you know, the

leather and the studded collars and the handcuffs and the choke chains and, I

mean, all the stuff that almost looks like fetish gear.

Mr. HALFORD: Well, it is, to some extent...

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. HALFORD: ...although maybe not so much now because...

GROSS: Because it's a genre now. It's...

Mr. HALFORD: Well, no, because I can spend some money on some outfits,

whereas before I had to go into the local S&M shop and pick up something for

2 pounds.

GROSS: Oh!

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. HALFORD: That's the truth of it all. Yeah, I used to go down to my

local--used to S-shop in London and put 10 quid down and try and grab a little

bit of this and little bit of that and slowly put it together, you know. But,

yes, we're--again, it's something that we're very proud of. For a number of

the early formative years of metal, the image was not really tying in to the

fierceness and the strength and power of the music. And we kind of stumbled

upon it with a song called "Hell Bent for Leather," which is very much a biker

anthem song. We actually started to use the motorcycle at that point, too.

So all of these things kind of connected and created the heavy metal look.

So, yes, blame us for that.

GROSS: Well, can you...

Mr. HALFORD: For the whips and the chains and the wristbands and so on.

GROSS: Can you talk a little bit more about what you related to about that

look? I mean, I know there's a song "Hell Bent for Leather," but, you know,

you didn't have to take that literally and use that as your look. So can you

talk...

Mr. HALFORD: Well, it's--I'll tell you--yeah, I'll tell you, it looked and

felt a lot better than silks and satins and Spandex. So, you know...

GROSS: Had you ever been wearing silks and satins?

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah. Well, you know, that's how it started out. I mean, if

you look at the very, very early, primitive videos of Priest going to Japan in

the mid- to late '70s, there was a combination of looks going on from the band

members. And we didn't really nail it down, so to speak, until we brought

about that song and started to kind of explore this territory. And it just

made absolute sense to us. I mean, you're wearing all of these studs that are

made of steel and metal. You've got the leather look, which is very tough and

has that kind of "Rebel without a Cause," "On the Waterfront" type of approach

and attitude. And so it just made absolute sense to go with that and develop

it.

GROSS: Did you think of it as a gay look?

Mr. HALFORD: No, I never did. I mean, you know--and I've been asked this

question numerous times. I can say, hand on heart, that was never my

intention. It was just coincidental that there's a portion of the gay

community that's into that kind of lifestyle. And that's it, just pure

coincidence.

GROSS: And this isn't meant to be as personal as it's going to sound, but was

all the leather and handcuffs and fetish gear an expression of your personal

lifestyle or just good theatrical costuming?

Mr. HALFORD: Well, that's a very good question. I'm sure if there was a

couch here for me to lay on and a psychiatrist...

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. HALFORD: ...he'd probably go, `Yep, that's what you were doing, Rob.'

Who knows? I don't know. As I said, it was never part of a deliberate intent

for me. But, yeah, I would hasten to say--because you're the first person

ever to ask me this question--that subconsciously that was my way of saying,

`Look, this is who I am.' But, you know, in my outward kind of conscious

level, that was never a thought because that would have meant that I would

have been using the band and my look for some kind of agenda, which I've never

had.

GROSS: When you say that it was in some ways a level of who you were, was it

like a fantasy level of who you were or...

Mr. HALFORD: Oh, yes. Yes. Well, I don't know. This is just kind of an

open, free-forming kind of thought here. No. I mean, I'm not particularly

attracted to that world or that fantasy element of what that lifestyle

presents. It's just of no interest to me personally. It's all about, in all

honesty, the fact that putting all that stuff on and looking at yourself in a

mirror before you went on stage felt absolutely the right thing to do.

GROSS: Well, since you've mentioned "Hell Bent for Leather," I think we

should hear it. So this is Judas Priest, "Hell Bent for Leather."

(Soundbite of "Hell Bent for Leather")

Mr. HALFORD: (Singing) Seek him here, seek him on the highway, never knowing

when he'll appear. All await, engine's ticking over, hear the roar as they

sense the fear. Wheels! A glint of steel and a flash of light! Screams!

From a streak of fire as he strikes! Hell bent, hell bent for leather. Hell

bent, hell bent for leather. Black as night, faster than a shadow, crimson

flare from a raging sun.

GROSS: That's one the classic Judas Priest recordings, "Hell Bent for

Leather." My guest is Rob Halford, who is the lead singer of the band. And

there's a new Judas Priest CD called "Angel of Retribution."

Did you like Westerns, too?

Mr. HALFORD: Oh, yeah. That's a great question. I'm glad you asked me that

because growing up in England as I did--I was born in 1951 and was just able

to afford a small black-and-white TV. But we would watch these Western shows,

you know, from--being pumped out from Hollywood, whether it was "The Lone

Ranger" or "The Cisco Kid" or "Champion the Wonder Horse." And these were all

based in the desert, you know, in Arizona or the Southwest. So there's still

an affinity with that kind of cowboys-and-Indians type of imagery that's loved

not only in the UK but of all over Europe, I would imagine. So one of the...

GROSS: And a lot of leather in there, I might say.

Mr. HALFORD: Oh, yeah. All those chaps.

GROSS: That's why I asked, yeah.

Mr. HALFORD: Yeah, exactly.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. HALFORD: All that sitting in the saddle. But, no--so, you know, for me

to actually watch that on TV as a kid and then to suddenly get off a bus in

Arizona at 3:00 in the morning after a trip down from Vegas in 1978 was just

mind-blowing, you know. And I woke up the next day and there was the cactus

and there was the desert and the roadrunners and the Gila monsters and the

rattlesnakes and the cowboys and Indians. And it was a dream come true.

GROSS: Rob Halford is the lead singer of Judas Priest. They have a new CD

called "Angel of Retribution." It's the first CD since Halford returned to

the band. He'll be back in the second half of the show. I'm Terry Gross, and

this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of "You've Got Another Thing Comin'")

Mr. HALFORD: (Singing) One life, I'm gonna live it up. I'm takin' flight; I

said, `I'll never get enough.' Stand tall, I'm young and kinda proud. I'm on

the top for as long as the music's loud.

If you think I'll sit around as the world goes by, you're thinkin' like a fool

'cause it's a case of do or die. Out there is a fortune waitin' to be had.

You think I'll let it go, you're mad. You've got another thing comin'.

You've got another thing comin'.

That's right, here's where the talking ends. Well, listen, this night

there'll be some action spent. Drive hard; I'm callin' all the shots. I got

an ace card comin' down on the rocks.

If you think I'll sit around and chip away my brain, listen, I ain't foolin'

and you'd better think again. Out there is a fortune waitin' to be had. You

think I'll let it go, you're mad. You've got another thing comin'. You've

got another thing comin'. You've got another thing comin'.

In this world we're livin' in we have our shares of sorrows. Answer now is

don't give in, aim for a new tomorrow.

(Soundbite of music)

(Announcements)

(Soundbite of "Ram It Down")

Mr. HALFORD: (Screams) Oh!

GROSS: Coming up, more with Rob Halford of Judas Priest. He'll talk more

about coming out and about the impact of the 1990 lawsuit that accused a

Priest recording of convincing two teen-agers to commit suicide.

Also, linguist Geoff Nunberg reflects on the act of memorizing poetry.

(Soundbite of song)

Mr. HALFORD: (Singing) Raise the sights, the city lights are calling. We're

hot tonight, the time is right; there's nitro in the air. In the street is

where we'll meet, we're warning. On the beat, we won't retreat, beware.

Thousands of cars and a million guitars screaming with power in the air.

We've found the place where the decibels race; this army of rock will be there

to ram it down, ram it down straight through the heart of this town. Ram it

down, ram it down, razing the place to the ground. Ram it down. Bodies

revvin' in leather, heaven in wonder...

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross back with Rob Halford, the lead

singer of Judas Priest, one of the first heavy metal bands. Halford started

singing with the band in 1971. He left in the early '90s and later surprised

his fans by coming out. Halford returned to the band a couple of years ago.

They have a new CD called "Angel of Retribution."

Judas Priest shows are quite theatrical experiences. How did you head in

that direction of making it, like, theatrical?

Mr. HALFORD: Well, it just comes from being a kid, you know. I mean, when I

was in my early grades at school, I was able to get into the school choir and

be a part of all of the school productions, much like a lot of kids do. And I

just ran to that. It made me feel good inside. Everybody likes to be looked

at and applauded, especially when you're a child. And I think that stuck with

me. So there was a point in my life when it was kind of a toss-up between

whether I was going to actually go from school--high school--into drama school

and drama university in England. But I chose to go with music because that

was the love of my life at that time, and it still is today. So I think I

brought that theatrical desire with me to Priest. And I was always, you know,

at the band meetings pushing for this lighting effect or that stage set or

these costume ideas or these smoke machines or, you know, pyrotechnics,

whatever it might be. Whatever is really theatrical came from my love of the

theater and the magic that it can make.

GROSS: For listeners who haven't seen your show, can you describe one of the

most theatrical things?

Mr. HALFORD: We have a moment going on in this current "Angel of Retribution"

worldwide tour that we do. We--there's an opening cut from "Angel of

Retribution" called "Judas Rising," and I appear behind the drum riser on a

50-foot hoist, a pneumatic man lift. And at the bottom of the hoist is

this theatrical flame fire effects. And so there's an intro--there's a piece

of intro type that works with that song, and the man lift, as it's called, is

being taken up to about 50 feet. And there's all of this smoke and fire

billowing around my feet, and I'm wearing this outfit made out of pure

reflective chrome and hit with, you know, two or three spotlights against a

backdrop of this larger-than-life, 100-foot-wide reincarnation of the "Angel

of Retribution" artwork. And it's absolutely spectacular. I mean, I can see

the reaction as that all comes together, and that's just one element of a

two-hour Judas Priest performance that the fans love.

GROSS: Is there part of you that stands back and says, `God, this is really

funny'? Do you know what I mean?

Mr. HALFORD: Honestly, you've got to have a "Spinal Tap" mentality.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. HALFORD: "Spinal Tap" helps, yeah, because, you know, you've got to be

able to laugh at some of these things and smile and enjoy them, which is not

to kind of take it as a joke or to humiliate it. But you've got to certainly

be able to kind of smile at some of these things that you do but in a loving

way and in a way that you're cherishing the moment. And you know the effect

that it's creating and how it's making you feel yourself as you bring that

effect to life. But, yes, certainly every band has a copy of "Spinal Tap" on

the tube or...

GROSS: So at its best, what does it feel like to come, you know, rising out

from--on this, like, hydraulic lift in your chrome costume with spotlights

shining on you. Like, what does that feel like on a really good night?

Mr. HALFORD: Well, I'll tell you what it feels like, Terry. It feels like,

`I hope the lift doesn't jam. I hope the smoke machine doesn't blow up. I

hope my microphone works at this height.' That's what it feels like.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. HALFORD: It's a complex run of emotions right up till I start singing the

song, but once the song is in full roar, it's just a very powerful, dominating

type of explosion that goes on for the duration of the song. It's a very

powerful song for us to perform because I think it embodies a lot of the

reunion aspects that we're still enjoying right now.

GROSS: So are there moments in performance now where you feel, `I am a heavy

metal god'?

Mr. HALFORD: Oh, yes. Every time I get dressed before I go on stage, and I

think that I can say that in all honesty that doesn't mean to say that I'm a

schizophrenic or a split personality. But definitely when you get dressed to

go to work, your persona changes. You're getting psyched up. Your attitude

is being prepared mentally. And much like a boxer going into the ring or a

basketball player going out to court, and you know there's a job to be done

with your teammates, and you're going to win. And so definitely there's a

feeling of confidence and a certain makeover that takes place.

GROSS: Well, why don't we hear "Judas Rising"? And this is from the new

Judas Priest album, which is called "Angel of Retribution."

(Soundbite of "Judas Rising")

Mr. HALFORD: (Singing) White bolt of lightning came out of nowhere, blinded

the darkness, creating the storm. War in the heavens, vengeance ignited.

Torment and tempest attack like a swarm. Forged out of flame from chaos to

destiny, bringer of pain forever undying. Judas is rising.

GROSS: That's "Judas Rising" from the new Judas Priest album "Angel of

Retribution." My guest, Rob Halford, is the lead singer of the band.

Now, you know, with Judas Priest titles like "Hellion," "Eat Me Alive,"

"Devil's Child," "Breaking the Law," "Screaming For Vengeance," "Beyond The

Realms Of Death," "A Touch of Evil," "Sinner," we can all see why parents in

the '70s and '80s weren't necessarily thrilled that their children were

listening to your records. What effect do you think your music has had over

the years on your teen-aged fans?

Mr. HALFORD: Well, our teen-aged fans have grown up now, and they're healthy,

stable, balanced, family-oriented fans. They bring their children to our

concerts. So if that isn't proof that Judas Priest has stood by nothing other

than giving people some escape and some great nights out when they see us live

and some very personal enjoyment at home on the headphones or on the speakers,

then I don't know what else to say. I'm at a loss for words. It kind of puts

to sleep that moment in the '80s when this--not only this band, even

individuals like Sheena Easton were attacked by a political agenda that really

had, in our opinions, some misconceptions.

There was the one side of it about protection, which was running very close to

censorship. But we all approved this PG rating. We thought it was a great

idea because some of us were using language and ideas that we felt it was

important to attach some kind of notification towards. But those songs that

you mentioned are but a handful of some, I don't know, two, 300 recordings

that we've made over the years. And it's like a lot of things that any

career-oriented creator makes. Little things pop out more than others, and

things get more attention than others.

GROSS: There was actually a lawsuit against Judas Priest, a now-famous

lawsuit, in 1985. And two teen-age boys tried to commit suicide; one of them

succeeded, one of them shot his face off and had it reconstructed with plastic

surgery. And one of the parents charged that they were inspired to commit

suicide by one of the Judas Priest records, which had a subliminal message

saying, `Do it.' What was your reaction when you heard about this?

Mr. HALFORD: Well, it was utter shock and disbelief and, again, dismay that

it was coming from a country that we'd had so many great times with. And you

can imagine--well, I guess you can't. But, I mean, to actually get off the

tube and be handed a subpoena by the deputy in Texas, I think it was or--no,

actually in Reno, but I think we were actually subpoenaed while we were in

Texas--to say, you know, `On this date, you have to leave your home country in

England, get on a plane and come to a courthouse in Reno and basically fight

for your life.' But we looked at this. We were very upset. We thought that

the allegations were completely ridiculous and without foundation. But the

only way we could put our side of the story across and to tell everybody the

truth was to go to Reno and sit in the courthouse for five weeks and deal with

each issue as it was presented to us. But that was just a very upsetting time

for all of us to go through.

GROSS: The judge ruled that the band had not intentionally placed subliminal

messages on the album. What was the most surreal part of the trial for you?

Mr. HALFORD: Well, the balancing act between the First Amendment, freedom of

speech and the so-called subliminal messages which--by my definition, if it's

a subliminal message, you don't even know what's happening or what's going on.

So their presentation of a subliminal message, which was a combination of both

breathing and some guitar effects, was just ridiculous. I mean, we dismantled

that theory and that allegation in the courtroom with recording equipment, and

we showed the judge very clearly how these strange quirks of sounds and

mysterious things that go on in recordings can actually make it on to a disk

and be misconstrued.

So it really was without foundation, but we had to go to the courtroom and

stand up for ourselves and to prove that we had not done this and that we

would never do this and there was never intent or any, you know, reason on our

part to actually do something like this. Oh, they'd say that, you know, `Why

on earth would any band want to go and kill its fans?' Because these two boys

were hard-core Judas Priest fans. They came from a very tough family life.

There was a history of alcohol abuse. There was a history of drug abuse, and

the boys were finding solace in the music of Priest. So it was after the

event really that they were approached by a group of people who we were led to

believe had connections with some of the more conservative religious elements

in America that urged them to take this to court to make a case out of it, but

as you said earlier, we came out of it clean, you know, which is the way it

should be.

GROSS: My guest is Rob Halford, the lead singer of Judas Priest. They have a

new CD called "Angel of Retribution." We'll talk more after a break. This is

FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Rob Halford, the lead singer of

Judas Priest, and the band's back on the road. They even have a new CD, and

it's called "Angel of Retribution."

I want to get back to something we were talking about a little earlier which

is coming out, and what year was it that you actually came out?

Mr. HALFORD: Do you know, I can't be absolutely precise. I would think it

was around '93, '4.

GROSS: OK. I imagine there were a lot of times when you were in a really

awkward position. I mean, for example, most bands have groupies. I'm sure

there were so many women waiting for you, you know, actually throwing

themselves at you, and, you know, how do you make it clear that, like, you

know, `No thanks'?

Mr. HALFORD: Well, that's it. I mean, I'm a very polite British gentleman.

`No thank you.' It's as simple as that, and I'm kind of proud of that. I'm

very proud of myself that I didn't go out onto this kind of extreme limb of

displaying myself in a way that was not truthful, which is to say that, you

know, I wasn't caught in those kinds of situations just because I felt it was

important to portray myself in a certain way, being a singer in a famous

heavy-metal band. You know, I couldn't do that, because again, I would have

been using myself, I would have been using a lot of different things that go

against my own particular standards. So, yeah, you say, `No thank you,' you

know, and leave it at that.

GROSS: Did you feel cut off from other gay people? Because if you felt you

couldn't come out, it probably meant you couldn't hang out with a gay crowd

and...

Mr. HALFORD: Ah, yes.

GROSS: ...so, like, you know, what do you do when you're on the road? Who do

you...

Mr. HALFORD: Well...

GROSS: ...hang out with?

Mr. HALFORD: ...yeah, again, this is all about surroundings and

circumstances in it because that was a world that I didn't really walk towards

or begin to investigate until I was probably in my mid-20s or so, which might

sound amazing to some people, but it never really interested me. I'm

still--I'm a conservative gay man and, you know, bars don't interest me, clubs

don't interest me. I'm still to some extent invisible within the gay

community and that's because I don't really seek to be, you know, a

spokesperson for whatever things are being discussed by other celebrities by

their choice. I feel that what I do is enough for me and, to a certain

extent, a cause, if any. By walking out night after night in front of

thousands of metal fans all over the world as a gay metal singer, that, to me,

is my cause and my moment for celebration.

GROSS: I also like to ask musicians on the show to redeem a song, to tell us

about a song that they love that we might be surprised that they love, that we

might think of as square or corny or sentimental or whatever. Would you do

that? Would you choose a song that you really love that you'd be--that you

think we might be surprised that you love?

Mr. HALFORD: Oh, OK. This is going to take a little bit--I might need a

prompt here, but, oh, Lord, there's a song by Hank Williams, and I have this

really cool double-CD set of Hank Williams, and I love his music because it is

so pure. It's so from the heart, and he has this wonderful, soulful voice,

and it's a story about this gal that lives in a mansion on the hill or a house

on the hill, and there's just something about that song. It's very appealing,

you know, because it's about a love lost and about the fact that because

there's a distance between the two strata, you know, she's up there on this

hill and he's in a different place and, you know, they can't connect because

of that bridge--I just think that's a wonderful song. And if you can find

that song for me and share it with the listeners, maybe that'll be a bit of a

surprise, but there you go. The metal god's a Hank Williams fan.

GROSS: We'll try to do that. One other thing: How do you take care of your

voice?

Mr. HALFORD: You know, I don't do a lot to look after my voice. I'm very

fortunate. I use it much like any musician uses an instrument. I know what

to do and what not to do. Physical rest is the best you can do. Taking as

much of a breather between shows and resting your voice is the best that you

can offer yourself. So that's about it really. I don't really do anything

else other than just get dressed and go to work. I don't generally warm up or

take any lotions or potions and incantations. It's all very straightforward.

I count my blessings. Some singers have to do certain things before they go

out on stage, but I just get dressed and start screaming.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. HALFORD: Thank you, Terry. It's been a pleasure.

GROSS: Rob Halford is the lead singer of Judas Priest. Their new CD is

called "Angel of Retribution." Here's the song he was just talking about,

"Mansion on the Hill," recorded by Hank Williams in 1948.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. HANK WILLIAMS: (Singing) Tonight down here in the valley, I'm lonesome

and, oh, how I feel. As I sit here alone in my cabin, I can see your mansion

on the hill. Do you recall when we parted? The story to me you revealed.

You said you could live without love, dear, in your loveless mansion on the

hill.

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Commentary: Practice of memorizing poetry

TERRY GROSS, host:

A few years ago, Ruth Lilly, the heir to a pharmaceutical fortune, left a $100

million bequest to Poetry magazine. The magazine's publishers have been using

some of that money to encourage the practice of memorizing poetry. Our

linguist Geoff Nunberg thinks that's a good idea.

GEOFF NUNBERG:

Digging into what have to be the deepest coffers of any literary publication

in history, the publishers of Poetry magazine recently joined with the

National Endowment for the Arts to hold the first of a series of recitation

competitions patterned after the National Spelling Bee.

I have to say, I'm a little uneasy about that model. The National Spelling

Bee is one of those odd competitions that turn an ordinary activity into a

high-performance event, like extreme ironing, and when you think of poetry

recitation contests, you might have the image of overachiever kids declaiming,

`The boy stood on the burning deck' with appropriate gestures while their

parents and elocution coaches watch nervously from the audience.

But that's probably unfair, and you have to welcome any program that might

encourage more learning of poetry by heart. After a half-century you could

think of as the great forgetting. In Xanadu did Kubla Khan, `I wandered

lonely as a cloud. We were very tired. We were very merry.' Nowadays,

high-school graduates don't recognize any of those lines. Where the hundreds

of others that used to paper the walls of the collective memory, only a few

scraps remain. Students may know the first stanza of "The Highwayman," which

comes in handy for teaching about metaphor: Is the poet saying that the moon

was really a ghostly galleon? They probably know Shelley's "My Name is

Ozymandias, King of Kings," which makes for a good lesson about irony, not to

mention about the futility of big government. And they almost certainly know

a bit of "Stopping By Woods On A Snowy Evening," which is pretty much the last

poem left in the American literary cannon.

That obliteration was already well under way when I was in grade school, and I

was spared some of its ravages only because I picked up the habit of

memorizing poetry from my dad who liked to recite to me when I was little, a

mix of patriotic ballads like Barbara Frietchie and light verse by the likes

of Don Marquis and the sadly forgotten Arthur Guiterman. I've tried to pass

on some of these to my daughter Sophie. She does an impressive job with the

beginning of "The Cremation of Sam McGee," though she generally loses the

track somewhere around `mushing our way over the Dawson trail,' but that's

normal.

Unless you're one of those freaks of nature who can soak this stuff up

effortlessly, most of what you've got left of the poems you've learned is

snips and snatches. `My heart aches and a something-something pains my

sense.' `I will arise now and go to whatchamacallit.' `To tum, to tum, your

mom and dad, they may not mean to but they do.' Yet the odd thing is that

once you've memorized a poem, you still own it even after you've forgotten

most of the words and have to Google it up the way everybody else does.

That's reason enough for learning poems by heart, and there's no need to sully

the case for memorization by claiming that it's good for mental discipline or

cognitive development.

Memorizing poetry does seem to make people a bit better at memorizing poetry,

but there's no evidence that the skill carries over to other tasks. For that

matter, it's doubtful whether memorization makes you a better writer, either.

The former poet laureate Robert Pinsky once suggested that anybody who's

memorized a lot of poetry can't fail to write coherent sentences and

paragraphs. There's probably some truth to that nowadays, since the only

people who know a lot of poetry by heart are the ones who are drawn to it out

of a love of language, but the Victorian schoolchildren who learned reams of

verse at the end of their teachers' canes grew up to write an awful lot of bad

prose, most of it happily lost to literary memory.

In fact, it's misguided to wax nostalgic for a time when students were

required to memorize sentimental ballads and patriotic rousers in the name of

character building and when kids who misbehaved were given 20 lines of poetry

to learn as punishment. Memorization back then was a kind of conscription.

The whole world learned to march to those regular four-beat rhythms that make

poems easy to learn.

The progressive educators of the 20th century were right to want to sweep all

that away, but they were wrong to dismiss memorization as mindless rote

learning as if the sounds alone communicated nothing by themselves. If you

think you can understand poems without feeling them in your body, you're apt

to treat them as no more than pretty op-ed pieces. You wind up teaching kids

to value the road not taken as merely a piece of sage advice about making

difficult decisions.

I was about seven or eight years old when my dad taught me "Scots, Wha Hae Wi'

Wallace Bled." I had absolutely no idea what the poem was about or even what

half the words meant, but I learned something else, how verse can become a

physical presence, in Robert Pinsky's words, which operates at the borderline

of body and mind. That's an experience that you can only live fully when the

poem comes from within rather than from the page in front of you. I like the

way the Victorianist Catherine Robson put this: `When we don't learn by

heart, the heart doesn't feel the rhythms of poetry as echoes of its own

incessant beat.'

GROSS: Geoff Nunberg is a Stanford linguist and author of "Going Nucular:

Language, Politics and Culture in Confrontational Times."

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.