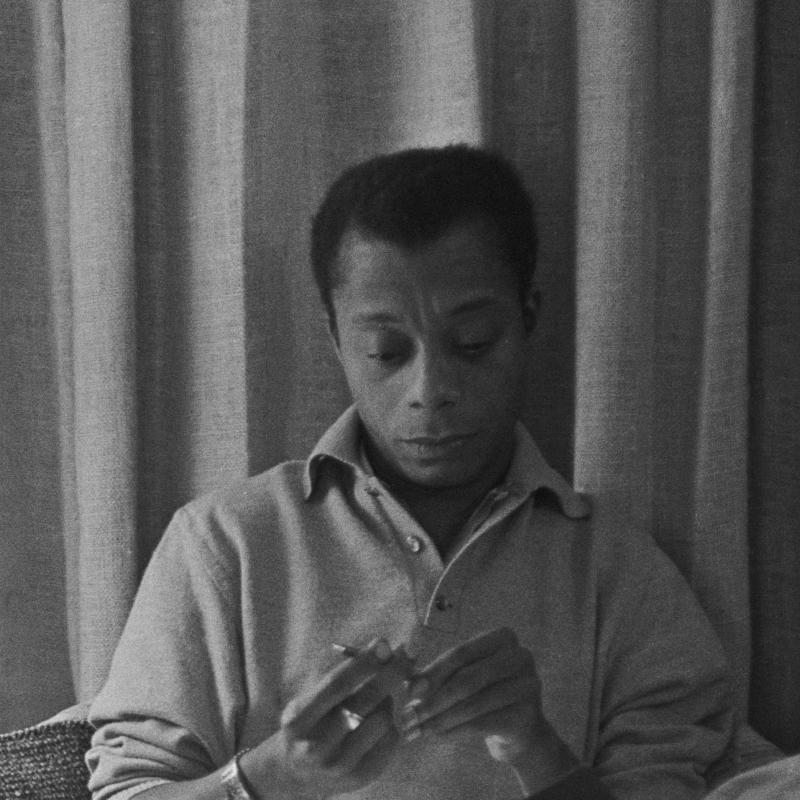

Writers Week: James Baldwin.

A rebroadcast of a 1986 interview Terry Gross recorded with writer and social critic James Baldwin, who died in 1987. Baldwin's books include Go Tell it on the Mountain, The Fire Next Time and Notes of a Native Son. Baldwin was one of the first major writers to address the civil rights issue. After the civil rights movement crested, Baldwin moved to France, where he felt more tolerance for his open homosexuality and outspoken nature. (REBROADCAST from 1986)

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on December 29, 1999

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: DECEMBER 29, 1999

Time: 12:00

Tran: 122901np.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Interview with James Baldwin

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:06

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: From WHYY in Philadelphia, I'm Terry Gross with FRESH AIR.

On today's FRESH AIR, as our Writers' Week continues, we go into the archive to listen back to interviews with writers who are no longer with us. We'll hear from James Baldwin, one of the greatest writers to emerge during the civil rights era, Wallace Stegner, the dean of Western writers, poet Jane Kenyon, and Paul Monette, who wrote about losing friends and lovers to AIDS before dying of it himself.

Also, classical music critic Lloyd Schwartz considers the most significant musical achievement of the century.

That's all coming up on FRESH AIR.

First, the news.

(NEWS BREAK)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

This is Writers' Week on FRESH AIR, featuring some of our favorite interviews with writers from our archive.

Today we're going to take advantage of the archive to listen back to writers who are no longer with us.

James Baldwin was one of the most influential writers to emerge during the civil rights era. His essays and novels addressed racial issues head-on. His best-known works include "Go Tell It on the Mountain," "Giovanni's Room," "Nobody Knows My Name," "The Fire Next Time," and "Another Country."

For most of his adult life, Baldwin lived as an expatriate in France. I spoke with James Baldwin a few months before his death in 1987. He told me that he grew up in Harlem, where his father was a preacher in a storefront church.

(BEGIN AUDIO TAPE)

JAMES BALDWIN: Daddy was an old-fashioned fire-and-brimstone hellfire preacher, you know, very direct, very chilling sometimes. His orders were not only coming from him but from the Almighty. So in a way to contest him was to be contesting, you know, the Lord, to be fighting the Lord, because my father was not slow to point this out.

GROSS: (laughs)

BALDWIN: There was something very frightening about it.

GROSS: You became a preacher when you were 14.

BALDWIN: That's right.

GROSS: Why did you do that?

BALDWIN: Well, it was almost inevitable, you know, being raised that way, and actually not doubting anything my father said, not doubting the Gospel, not doubting the church, you know. And at the time of puberty, when everybody goes through a storm -- you know, the storm of self-discovery, the storm of self-intent, the storm of -- the terror of, who is this self which is suddenly evolving, no suddenly -- is distinguishing itself from other selves?

And all of these things -- and the sexual question, of course, you know, all of these things sort of coalesce into some kind of hurricane, in a way, you know. And in that hurricane, I -- what do I do? I reached out for the only thing I could -- which I knew to cling to, and that was the Holy Ghost.

GROSS: So by being a preacher, you didn't have to -- you were able to, like, put on the back shelf for awhile sexuality and entering adulthood and those kind of things.

BALDWIN: Well, it didn't work, actually, you know. I mean, I was in the pulpit for three years, and all the -- well, all of the elements which had driven me into the pulpit, you know, were still there, were still active, were still -- I was not less menaced.

And in those three years in the pulpit, it's very difficult to describe them, I probably shouldn't try. There was a kind of torment in it, but there was -- but I learned an awful lot. And my faith, perhaps -- I lost my faith, all the faith I'd had.

But I learned something else, I learned something about myself, I think, and I learned something through dealing with those congregations. After all, I was a boy preacher, and the people I was -- the congregations I addressed were grownups.

And a boy preacher has a very special aura in the black community. And that aura implies a certain responsibility, you know, and the responsibility above all to tell the truth.

So as I began to be more and more tormented by my crumbling faith, it began to be clearer and clearer to me that I had no right to stay in the pulpit. And I didn't know enough, I didn't -- the suffering of those people, which was real, was still beyond the ken of a boy 14, 15, 16. You could respond to it, but I had not yet entered that inferno.

They knew something about being a nigger, which I was only just beginning to discover, and it frightened me.

So for those reasons and complex reasons, I left, I left home, and I left the church.

GROSS: What did you do to try to get your foot in the door somewheres as a writer?

BALDWIN: Oh, I wrote all the time, you know. I worked -- I was work -- I worked all day, and I wrote all night. And I learned a lot. I began to be being published when I was 22. I had a fellowship when I was 21.

And something else was happening too, though I didn't quite see it. I was just -- I was defined as a young Negro writer, and that meant that certain things were expected of a young Negro writer. And what was expected, I was not -- I knew I was not about to deliver. What was expected was to -- putting it very brutally, but what was expected was to accept the role of victim and to write from that point of view.

And from my point of view, it seemed to me that to take such a stance was -- would simply be to corroborate all of the principles which had you enslaved in the first place.

GROSS: "Go Tell It on the Mountain" was a fairly autobiographical novel, and it really won you a lot of attention and prestige in America. Your book of essays, "The Fire Next Time," which was published in 1963, was, I think, perceived by many whites as an attack against whites, like, He's threatening us with the fire next time.

Did that happen, did some white people see it that way, and did it change your reputation to becoming more of a controversial writer?

BALDWIN: Yes, but that happened -- that had begun to happen already without my quite noticing it. It was long before "The Fire Next Time," which was written as an attack on white people. They flatter themselves.

GROSS: (laughs)

BALDWIN: Long before that, when I first got South, first went South and tried to begin to -- because I went as a reporter there, and I tried to get the story published, you know. The first few times, I -- the first few magazines, when I came back, did not want to publish the reports, because they accused me of fomenting violence. And I was describing violence, which is not -- violence for which I was in no way responsible.

And I thought that people should know what is going on and why it's going on. And in the battle, you know, to do this, I became notorious. In any case, the battle I was fighting, it seemed to me, was not simply about black people but also my position as concerns (ph) white America was, It's your country too. It's your responsibility too, you know.

And "The Fire Next Time" is probably a combination of all those years, you know, it was when I was being called the angry young man on the white side of town, and being called Uncle Tom on the black side of town.

GROSS: You've been very outspoken about civil rights issues and about black issues in America, but you've been much less outspoken about homosexual issues. And...

BALDWIN: Well -- Go ahead.

GROSS: And I'm just thinking that in a way, homosexuals have been marginalized in both the white and black parts of American culture.

BALDWIN: Well, there's no point in mixing the two questions, because it only leads to terrible confusion. And in America, in any case, the homosexual question is tied up with the whole American ideal of masculinity, the whole infantile idea, according to me.

And absolutely untrue. To be a man is much more various than the American myth has it. It seems to me that I have -- I myself have lived the life that I've observed, that love is a very -- love is like the lightning or like -- Love is where you find it, you know. And your maturity, I think, is signaled by the depth or the extent to which you can accept the dangers and the power and the beauty of love.

GROSS: Some of your writing has really been, I think, very important to gay people and people in the gay movement in America. And I wonder if the gay liberation movement had any effect on you, if it was important for you to have, you know, a movement about that.

BALDWIN: No, no, no, no. I left the church when I was 17, I have not joined anything since. You see, when I was -- before I left this country, I had been afflicted with so many labels that I'd become invisible to myself, you know.

GROSS: (laughs)

BALDWIN: I had to go away someplace and get rid of all these labels and find out not what I was, but who. Do you see what I mean? And the liberate -- the gay liberation movement is ideally an attempt precisely to find out not what one is but who one is, and also to have no need to defend oneself, you know.

So it was a very simple matter for me, in any case, to say to myself, I'm going this way, you know, and only death will stop me, you know, and I want to live my life, the only life I have, in the sight of God.

(END AUDIO TAPE)

GROSS: James Baldwin, from our archive. He died in 1987.

Coming up from the archive, an interview with the late Wallace Stegner, the dean of Western writers.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia, PA

Guest: James Baldwin

High: A rebroadcast of a 1986 interview with writer and social critic James Baldwin, who died in 1987. Baldwin's books include "Go Tell It On The Mountain," "The Fire Next Time" and "Notes of a Native Son." Baldwin was one of the first major writers to address the civil rights issue. After the civil rights movement crested, Baldwin moved to France, where he felt more tolerance for his open homosexuality and outspoken nature.

Spec: Entertainment; James Baldwin; Literature

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1999 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1999 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Interview with James Baldwin

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: DECEMBER 29, 1999

Time: 12:00

Tran: 122902NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Interview with Wallace Stegner

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:22

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

GROSS: This is Writers' Week on FRESH AIR.

Today, we're going into the archive to listen back to interviews with writers who are no longer with us.

Wallace Stegner was called the dean of Western writers. He didn't write about myth, he wrote about the landscape and how it was changed by development, and he wrote about the people who settled the West and the generations that followed.

But as one critic wrote, "Stegner's main region was the human spirit, how one achieves a sense of identity, permanence, a sense of home, in a place where rootlessness and discontinuity dominate."

Stegner was born in 1909 and grew up in a family that moved from place to place across the West. He won the Pulitzer Prize for his 1971 novel, "Angle of Repose." For 26 years he headed the writers' program at Stanford University.

He died at the age of 84 in 1993, of injuries sustained in a traffic accident.

I spoke with Wallace Stegner in 1992. We began with a reading from the introduction of his 1992 book of essays called "Where the Bluebird Sings to the Lemonade Springs: Living and Writing in the West," in which Stegner wrote about the true believers and wishful thinkers who settled the West -- people like his father.

(BEGIN AUDIO TAPE)

WALLACE STEGNER: "I know that historical hope, energy, carelessness, and self-deception. I knew it before I could talk. My father practically invented it, though he qualified more as sucker than as booster and profited accordingly.

"He was a boomer from the age of 14, always on the lookout for the big chance, the ground floor, the inside track. As a youth, he tried the Wisconsin and Minnesota woods but found only the migratory wage slavery that's always been one payoff of the American dream.

"He tried professional baseball but wasn't quite good enough. In the 1890s, he floated out to North Dakota on the tail end of the land rush, but found himself in the midst of a 10-year drought and ended up speculating in wheat futures and running a blind pig.

"If you believe that the world owes you not merely a living but a bonanza, then restrictive laws are only an irritation and a challenge.

"When it became clear that Dakota's promises were indistinguishable from Siberian exile, my father dragged us out the migration route to the Northwest. His goal then was Alaska, but again he was late. The Klondike rush was long over; the survivors had straggled back.

"For a while, he ran a lunchroom in the Washington woods where the Seattle suburb of Redmond now is. The loggers cut down the trees and left the lunchroom among the stumps.

"By 1914, we were up in Saskatchewan, part of another land rush, where, for a change, we would be in on the ground floor and make a killing growing wheat to feed Europe's armies."

GROSS: Do you think of your father's personality as being typical of a certain kind of restless loser who populated the West?

STEGNER: Not always losers. You know, he was characteristic, I think, but sometimes they were losers and sometimes they were big winners. He was a product of his times, and though I used to resent him a great deal, I find that now I feel rather sorry for him.

I think he was made by his times, at the end of the frontier, when there was no longer the kind of frontier opportunity that for so long had been part of the American consciousness, and he tried a lot of things, and none of them worked, or very few of them worked.

GROSS: So did you really resent it when you were young, and every time he had a new scheme you had to move?

STEGNER: Well, he was -- not that so much, as he was a frustrated man, and sometimes he took out his frustration on whatever was handy. But that too I can understand. I'm sometimes frustrated, and I take it out on some people too.

GROSS: You write, "My father wanted to make a killing and end up on Easy Street. I wanted to hunt up and rejoin the civilization I had been deprived of."

Where did you go looking for it?

STEGNER: Oh, school and the public libraries, primarily. This -- there was a big, big division between my home life -- because neither of my parents was educated, even through high school, even to high school, so that there was no background of cultivation, reading, anything else. Though my mother was a reader, she didn't know what to read. She had no guides. She would have had a good deal of cultural capacity, you know, if she'd had any guidance, but she didn't.

And I got mine from school and from the public libraries, where, you know, I took out seven books a week and read most of them. (laughs)

GROSS: Had you grown up on the myths and the folklore and the cliches of the West, you know, the cowboy stories?

STEGNER: Oh, sure. I grew up not only on the myth but among the cowboys. When we moved to Canada, we were in the tail end of a period of cattle raising, which had been pretty well wiped out in 1906 and '07 by a terrible winter. But in the protected edge of the hills where we lived, there were still cattle ranches.

And lots of cow punchers still working on ranches, hired men on horseback. They weren't the romantic figures that the myth made of them. They were also, as a class, I should say very much, oh, somewhat callous, somewhat brutal. Nice guys, in a way, but brutal. And I -- they also had a code of, you know, hating the crybaby, hating anything unlike themselves, despising anything womanish or oversensitive.

GROSS: There might have been no room there for somebody who spent a lot of time reading, like you.

STEGNER: Well, I -- you know, I got into -- in the cowboy business quite a lot as a boy. But by the time I moved out of it, I was a little tired of it, because I had some little physical defects. My hands were always cold, for one thing, and you can't live in Saskatchewan with cold hands and like it.

(LAUGHTER)

STEGNER: Things like that. So that I resented, sometimes, the harshness of the cold, though I was always trying to live up to it.

GROSS: But what about reading? Where did that fit in? I mean, for the kind of brutal macho code that you're describing, that doesn't seem to (inaudible)...

STEGNER: Well, there wasn't any reading up there...

GROSS: ... (inaudible) library, yes.

STEGNER: Up in Canada (ph), you know, there was no public library. Every family there may have had three books. We traded them all over town. Sometimes they never came back. My father at one point in his life got excited about -- I guess he'd seen a Shakespeare play, so he bought a set of Shakespeare from a traveling salesman. We had that. We had a few things like that.

Mostly what we read was magazines, I suppose. And later, when we got onto them, Tarzan stories and things like that.

GROSS: I grew up in Brooklyn, New York, but when I was young, my dreams were about being a cowgirl. I mean, I would literally dream (laughs), you know, about riding a horse and wearing a leather outfit and, you know, the whole Western myth. I grew up watching Westerns in the movies and on TV, and I just loved them.

And I'm wondering, like, growing up in the West and that knowing actual cowboys, what effect those kinds of movies and novels had on you. You grew up before television.

STEGNER: They -- sure, I grew up a long time before television. And I was never actually very taken by the Western myth because I knew how far it was from the actual facts. A cowboy's life is spent punching post holes and branding and castrating and things like that, very hard work and very low pay, and his celebrated liberty is generally the liberty to quit his bad job and go get another just as bad.

You know, in terms of his migratoriness, his placelessness, his uprootedness, he was very often as bad off as a contemporary crop worker. And he's not a romantic figure in life, though very often real cowboys imitate their mythical counterparts and try to think themselves into that role.

So I'm a little anti-cowboy. You've got the wrong coon (ph) here to talk to.

GROSS: At what point in your life did the West start to become a place that was considered to be a place that had writers living there writing about the region with a distinctive voice, publishers from the region publishing those distinctive voices?

STEGNER: That came pretty late in my life. I had graduated from college, I think, at the age of 20 or 21, before I ever saw a writer. It seemed to me that writers were people who lived a long time ago and a long way off. And it never occurred to me that I could be one or should be one, even though I liked to write, and, you know, was encouraged a little bit in school.

I suppose that never occurred to me, really, to take seriously the notion of being a writer until I went away to graduate school in Iowa, and there I was offered the chance to write some stories for an M.A. thesis and jumped at the chance.

And, you know, a couple of those were published in little magazines or so, and that's the extent of that. And I -- that was the middle of the Depression, and I couldn't stay on -- there was no job outside, so I stayed on in school, but I couldn't stay on just to be a writer, so I took a Ph.D. in American literature. And that pretty well killed the writing impulse for several years.

GROSS: (laughs)

STEGNER: Takes a long time to get over that.

But about two years after that, I was back teaching in Salt Lake, and I sat down one afternoon and wrote a story in about three hours about Saskatchewan. And somebody -- I guess "The Virginia Quarterly" -- bought it, and then I was hooked.

But that was pure accident. I -- in Iowa, I had met a few writers, and I'd certainly got a notion that writing was something that happened among contemporary living people. But it still hadn't jarred my consciousness that I could pretend to compete in that area.

(END AUDIO TAPE)

GROSS: Wallace Stegner, recorded in 1992. He died the following year after a traffic accident. He was 84.

More interviews with writers from our archive on the second half of the show.

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia, PA

Guest: Wallace Stegner

High: Writer Wallace Stegner's novels and essays were often based in the West where he grew up and lived for many years. Stegner started the creative writing program at Stanford University in California, which he ran for 26 years. In 1971 he won the Pulitzer Prize for his novel "Angle of Repose." One of his most popular books was 1943's semiautobiographical "Big Rock Candy Mountain." He died in 1993. (Rebroadcast from 4/15/92)

Spec: Entertainment; Wallace Stegner; Literature

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1999 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1999 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Interview with Wallace Stegner

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: DECEMBER 29, 1999

Time: 12:00

Tran: 122903NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Interview with Jane Kenyon

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:30

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

It's Writers' Week on FRESH AIR, and today we're going into the archive to listen back to interviews with great writers who are no longer with us.

The poet Jane Kenyon died of leukemia at the age of 47 in 1995. Her poems reflected her struggle with depression, but as critic Lloyd Schwartz, a friend and admirer, said, "Beneath the darkness was profound and spiritual optimism."

In fact, Kenyon often wrote about the restorative power of nature, even in the midst of depression and illness.

I spoke with Jane Kenyon and her husband, Donald Hall, in September of 1993. They were married for about 20 years. They lived in New Hampshire, where they had each served as the state's poet laureate.

Ironically, much of the interview was about how they dealt as a couple with Donald Hall's cancer. It wasn't until several months later that Jane Kenyon was diagnosed with leukemia.

We began with Kenyon reading an excerpt from a poem she'd written about her husband's cancer surgery.

(BEGIN AUDIO TAPE)

JANE KENYON: Chrysanthemums.

The doctor averted his eyes while the diagnosis fell on us,

As though the picture of the girl hiding from her dog

Had suddenly fallen off the wall.

We were speechless all the way home.

The light seemed strange.

A weekend of fear and purging.

Determined to work, he packed his Dictaphone,

A stack of letters, and a roll of stamps.

At last the day of scalpels, blood, and gauze arrived.

Eyes closed, I lay on his tightly made bed waiting.

From the hallway, I heard an old man

Whose nurse was helping him to talk.

That Howard Johnson's, it's nothing but the same thing

Over and over again.

That's right, it's nothing special.

Late in the afternoon, when slanting sun

Betrayed a wad of dust under the bedside stand,

I heard the sound of casters and footsteps slowing down.

The attendants asked me to leave the room

While they moved him onto the bed,

And the door remained closed for a long time.

Evening came. While he dozed, fitfully,

Still stupefied by anesthetics,

I tried to read, my feet propped on the rails of the bed.

Odette's Chrysanthemums were revealed to me,

Ranks of them, in the house where Swann,

Jealously constricting his heart,

Made late-night calls.

And while I read, pausing again and again

To look at him, the smell of chrysanthemums

Sent by friends wavered from the sill,

Mixing with the smells of drastic occasions

And disinfected sheets.

GROSS: That's an excerpt of Jane Kenyon's poem "Chrysanthemums." And the poem was included in her new collection of poetry, "Constance."

When you write a poem that's about Don, or Don, when you write a poem that has to do with Jane, do you show it to each other right away?

KENYON: Not right away, but we always work today on poems, (inaudible)...

GROSS: Even the poems about each other?

KENYON: Oh, yes, yes. We also work with other friends, each of us has our own committee, you might say, and we work very closely with other friends. But we do indeed work on each other's poems. And there are times when we just -- I simply have to say to Don, Well, I can't tell you about this, because I just can't get far enough away from it to have much judgment about it.

GROSS: Jane, at what point in the development of "Chrysanthemums" did you show the poem to Don?

KENYON: Well, it was many months after I started it. And I felt uncomfortable about this poem because I was revealing very personal things in it. And I wasn't sure how Don would feel about it. And I remember prefacing my showing this poem to him by saying, "You may feel that this is too personal, and that I didn't have a right to reveal these things."

It's best to be careful about hurting people in this way.

DONALD HALL: Because I wasn't hurt at all, but, I mean, I suppose I'm glad to be asked.

GROSS: And in -- and Don, did you work on that poem at all?

HALL: I can't remember -- I mean, almost always I have something to say. It's famous in our house that Jane will show me a poem and I'll say, "This is going to be good," and Jane will say, "Going to be, eh?" You know, I mean...

GROSS: (laughs)

HALL: ... I love her poetry. But oh, I'm tell -- I'm always telling her to take out the word "and" there, and take the comma out here, take this line from the end of one line and put it at the beginning of the next. And she tells me the same things, of course, endlessly. And we often do what the other says, but not always.

I don't remember what in particular I said about this, but the fact that it was about me and my illness would not keep me from having ideas about the sound of it, the style of it, the poetry of it. I mean, at first I read it, it's a poem about me, ka-bump, I'm struck by it. And then I -- by that fact. And then I start hearing the cadences and looking at the images. And if I see anything that doesn't sound quite right to me, I'll tell her. That's what we're useful for to each other in this particular way.

GROSS: Is there ever any friction between the two of you of who has ownership of a certain experience that you both shared, you know, and who has more of the right to write about it?

KENYON: Well, sometimes when something particularly piquant happens to us, one of us will say, "Jump ball."

(LAUGHTER)

HALL: Or, "Dibs." I remember being with a bunch of poets years and years ago back at Ann Arbor. Jane was one of them. And somebody said something terrific, you know, a good phrase, just adjective and noun or something. And everybody started yelling, "Dibs, dibs!" on that.

I don't think that we've really had any friction on this. We have written about the same thing, but we write differently enough, we can do that, it's all right.

GROSS: You've both written about battles with depression, and I'm wondering if you think it makes you more sensitive to each other's mood swings, or if it causes certain problems if you're not on the same mood swing schedule, so to speak.

KENYON: We try to arrange to have -- so that one person -- so that we're not both down or both up at the same time (inaudible). I think that we try to arrange for one of us to be manic and the other depressed at the same time, so that we -- you know, it's like Plato's ball -- or is it Plato or Socrates? -- who first imagined the human being as a sphere, you know. If you put us together, if you put the manic and the depressive together, press them together into a ball, you'd have a whole human being.

And I've often thought that if someone took the two of us and shook us up in a brown paper bag, and turned us out, there would really be one complete human being. (laughs)

(END AUDIO TAPE)

GROSS: Poets Jane Kenyon and Donald Hall, recorded in 1993. Kenyon died of leukemia in 1995.

Coming up, as our Writers' Week series continues, Paul Monette, who wrote about AIDS before dying of it himself.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia, PA

Guest: Jane Kenyon, Donald Hall

High: Poet Jane Kenyon's books include "Boat of Quiet Hours" and "Let Evening Come." Her collection "Otherwise" was published shortly after her death in 1995 of leukemia. The new book "A Hundred White Daffodils" is a posthumous collection of her prose and poetry. (Rebroadcast from 9/1/93)

Spec: Entertainment; Jane Kenyon; Literature

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1999 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1999 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Interview with Jane Kenyon

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: DECEMBER 29, 1999

Time: 12:00

Tran: 122904NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Interview with Paul Monette

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:45

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

GROSS: This is Writers' Week on FRESH AIR, and today we're going into the archive to listen back to writers who are no longer with us.

In the last two decades of this century, we lost many great artists to the AIDS epidemic. After chronicling what it's like to lose friends and lovers to AIDS, writer Paul Monette died of complications from AIDS in 1995. He won a National Book Award in 1992 for his memoir, "Becoming a Man." It focused on life before the AIDS epidemic, when he was coming of age and was afraid to come out of the closet.

He became nationally known after the publication of his 1988 memoir, "Borrowed Time," which described how he nursed his lover of 12 years, Roger Horowitz (ph), while Horowitz was dying of AIDS.

Monette later lost a second lover to the epidemic.

In 1988 on FRESH AIR, he read from the opening of "Borrowed Time."

(BEGIN AUDIO TAPE)

PAUL MONETTE: "I don't know if I will live to finish this. Doubtless there is a streak of self-importance in such an assertion, but who's counting? Maybe it's just that I've watched too many sicken in a month and die by Christmas, so that a fatal sort of realism comforts me more than magic.

"All I know is this: the virus ticks in me. And it doesn't care a whit about our categories. When is full-blown? What's AIDS-related? What is just sick and tired?

"No one has solved the puzzle of its timing. I take my drug from Tijuana twice a day. The very friends who tell me how vigorous I look, how well I seem, are the first to assure me of the imminent medical breakthrough.

"What they don't seem to understand is, I used up all my optimism keeping my friend alive. Now that he's gone, the cup of my own health is neither half full nor half empty -- just half."

(END AUDIO TAPE)

GROSS: Paul Monette returned to FRESH AIR in 1992, less than a year after he'd been diagnosed with AIDS, just a month after three brain lesions were discovered. I asked him to think back to that passage that he'd read four years before about having used up his optimism trying to keep his lover alive.

(BEGIN AUDIO TAPE)

MONETTE: They seem very prophetic to me now. What is poignant, Terry, is that I really did have -- I came back to a level of optimism, I think, a couple of years ago when I really believed, along with a lot of other AIDS activists, that we were on the brink of turning AIDS into a chronic, manageable illness. That was our phrase, and that was our hope.

And it really seemed to be backed up by the excitement in the medical community. That has changed. There's much more of a sense of darkness and despair, and how hard the long term is going to be in the AIDS activism community now.

I think ultimately we will turn this into that chronic manageable illness, but I will not live to see it.

GROSS: You've taken care of two lovers who died of AIDS. Do you have a lover now to help take care of you?

MONETTE: I do. I've been very fortunate, and I've met a wonderful strong man who buried a lover to AIDS about -- hm, oh, I would -- nearly a year ago now, eight or nine months ago. His name is Winston. And, you know, we understand that we're loving in the midst of war, and that the bombs could go off at any moment.

It's a very difficult position to be in, though. I would -- I mean, I -- it is difficult enough to care for somebody and to watch them die and to be unsure about when that's going to happen. It's heartbreaking to be in the position of being sick and to watch someone else worry.

GROSS: Are there times when you look at your lover and see yourself, because you've been through this?

MONETTE: Oh, so much. I so much see the -- a kind of quality of positive denial, whereby he is able to -- or insists on maintaining a positive attitude about it and me, and that reminds me very much of how I got through with Roger during those 20 months.

I felt in a way that one mistake I had made in treating Roger and in caring for him was that I really hadn't talked much with him about death, and I remember my therapist said to me after Roger died, and I was feeling guilty about that, "Well, you know, guess what, you would have had a conversation, and you would have both decided that death sucked, and that would have been that."

I mean, I think that's probably true. I don't know what to say about death, and here I am facing it.

GROSS: When your lover Roger died, in '86, I don't -- did you feel like that was it at all, do you know, ever, that -- like you wouldn't be able to have another lover again because the loss was so great? Or did you feel different than that, like, life is short, and you were going to keep your heart open to other people?

MONETTE: I went from the first feeling to the second feeling over a period of about a year and a half. In the months after Roger died, I was crazy. I just was an insane person. I mean, the grief hit me like insanity. I remember thinking that the only reason to get up in the morning was that the dog had to be fed. I mean, I was that close to a kind of inside suicide.

And I also had a record to leave. I mean, whatever writerly passion or ego had survived Roger's death consumed me during the next year as I wrote about him. And that definitely got me through.

And I assumed that I would be diagnosed with some horror at any time, at any time. But by the time I met Steven (ph), in the summer of '88, I really did feel just as you said, I felt, you know, I might as well take a chance. What else is there?

I've come to believe that -- I mean, I -- one of the things I say a lot is that I would rather be remembered for loving well than writing well. I -- as I said in "Borrowed Time," I think that when people come to the end of their lives, as I've watched so many people do, what matters to them is how much they've loved.

And, you know, as they say out here, nobody ever wanted to read one more screenplay on his deathbed.

So I was open to it. Steven was less open to it. I had to pursue him, I think. And he said to me when I met him, "You know, I have seven friends who are going to die in the next six months," and they did, one after another. And it took a great, great toll on him. And at the end of that six months, he was diagnosed himself with K.S.

But as I said to him after we'd been together for about a year, a year and a half, it was quite clear to both of us that we were able to be happy despite all the rage and pain we felt, because loving one another was so -- what we had spent our lives trying to find.

GROSS: You have a new memoir, and it's basically -- it's really your coming-out story, and the story of what your life was like when you had to cover up for who you were, and you had to lie a lot before you came out. And you write in that book that every memoir now is a kind of manifesto.

Before I ask you to read the opening of your new memoir, "Becoming a Man," how sick were you when you were writing this? During how much of the time of writing this were you actually sick?

MONETTE: Fortunately, I was really not sick except for fevers during most of the year that I wrote this book. I had wanted to write it because so many people had said to me about my relationship with Roger that it seemed like the perfect relationship, and they romanticized it a good deal. And as well they might, it was an incredible relationship.

But I would often think, God, if anybody really understood the loser and the lost that I was during the 25 years before I met Roger, I probably need to tell them that, that I was the most -- to me, anyway, the most unlikely person to find a great love. And that's what spurred me on.

What I didn't expect was how difficult it would be to actually confront the past honestly. And during the first 50 pages of it, I would think, Oh, everyone should do this, this is very exciting. And by the time I reached page 100, I thought, Nobody should do this, it's too depressing.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Paul, let me ask you to read the beginning of your new memoir, "Becoming a Man."

MONETTE: OK. It begins with a kind of manifesto, actually.

"Everybody else had a childhood, for one thing, where they were coaxed and coached and taught all the shorthand. Or that's how it always seemed to me, eavesdropping my way through 25 years, filling in the stories of straight men's lives. First they had their shining boyhood, which made them strong and psyched them up for the leap across the chasm to adolescence, where the real rites of manhood began.

"I grilled them about it whenever I could, slipping the casual question in while I did their Latin homework for them, sprawled on the lawn at Andover under the reeling elms.

"And every year they leaped further ahead, leaving me in the dust with all my doors closed, and each with a new and better deadbolt.

"Until I was 25, I was the only man I knew who had no story at all. I'd long since accepted the fact that nothing had ever happened to me and nothing ever would. That's how the closet feels once you've made your nest in it and learned to call it home. Self-pity becomes your oxygen.

"Forty-six now, and dying by inches, I finally see how our lives align at the core, if not in the sorry details. I still shiver with a kind of astonished delight when a gay brother or sister tells of that narrow escape from the coffin world of the closet.

"Yes, yes, yes, goes a voice in my head. It was just like that for me."

(END AUDIO TAPE)

GROSS: Paul Monette, recorded in 1992. He died of AIDS in 1995.

Our Writers' Week series continues tomorrow on FRESH AIR.

Coming up, our classical music critic, Lloyd Schwartz, on the most significant musical development of the 20th century.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia, PA

Guest: Paul Monette

High: Poet and novelist Paul Monette died of complications from AIDS in 1995, at age 49. His 1988 book "Borrowed Time: An Aids Memoir," was the first such memoir to be published about AIDS, and won a National Book Award. In it, Monette told the story of his friend and lover's two year struggle with AIDS. In 1992, Monette wrote a memoir about his own life before he came out of the closet at the age of 25, "Becoming a Man: Half a Life Story." (Rebroadcast from 7/20/92)

Spec: Entertainment; Paul Monette; Literature

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1999 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1999 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Interview with Paul Monette

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: DECEMBER 29, 1999

Time: 12:00

Tran: 122905NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: 20th Century Music To Remember

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:52

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

GROSS: We asked our classical music critic, Lloyd Schwartz, what he most wants to remember about music in the 20th century. Here's what he told us.

(AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, "THE RITE OF SPRING," IGOR STRAVINSKY)

LLOYD SCHWARTZ, CLASSICAL MUSIC CRITIC: It was arguably a musical event that first made the 20th century the 20th century. I'm thinking of the riot at the opening night of Igor Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring" in 1913, with controversial choreography by the great dancer Vaslav Nijinski.

The story of the ballet had to do with fertility rituals of ancient Russia, but Stravinsky gave us the jagged rhythms and complex harmonies of a modern age.

Of course, there's no way to reproduce what happened at that notorious event, but the original conductor, Pierre Monteux, has recorded the music, and so has Stravinsky himself. And it was recordings that made the 20th century different from all previous centuries.

They captured not only music but specific performances. In the new century, we will still be able to hear what the great conductor Artur Nikisch sounded like in 1913, or Bessie Smith in the 1920s, Arturo Toscanini in the '30s, Lotte Lenya and Maria Callas in the '50s, or the Beatles in the 1960s.

At this cosmic turning point, I'd like to pay tribute to the old recordings made on the 78 RPM shellac disks that were played on those wind-up Victrolas, the fragile technology that rescued from oblivion some of the most wonderful music-making the world has ever heard.

Maybe the musician who is dearest to me is the pianist Artur Schnabel, who, for example, rediscovered Schubert's extraordinary but long-forgotten last piano sonatas. Here's Schnabel playing part of the slow movement of Schubert's Opus Posthumous Sonata in B-flat, recorded in 1939. No musician was ever more unflinching about human tragedy or saw more profoundly how music was a source of consolation.

(AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, FRANZ SCHUBERT'S OPUS POSTHUMOUS PIANO SONATA IN B-FLAT, FRANZ SCHUBERT, ARTUR SCHNABEL)

SCHWARTZ: The greatest violinist I've ever heard is the Hungarian, Josef Sagetti (ph), who was a champion of both very old and very new music. Here he is playing the unplayable concerto that became part of the standard modern repertoire because he played it all over the world, Prokoviev's Violin Concerto Number 1. Like Schnabel, Sagetti let music not only sing but also speak. This performance, conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham, was recorded 64 years ago, and it's still the best one ever made.

(AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, SERGEI PROKOVIEV'S VIOLIN CONCERTO NUMBER 1, JOSEF SAGETTI)

SCHWARTZ: Someone once told me that the greatest single note ever recorded was the first note played by Pablo Casals on his 1937 recording of the Dvorak Cello Concerto, with George Szell and the Czech Philharmonic. The notes that follow it ain't so bad either.

(AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, ANTONIN DVORAK'S CELLO CONCERTO, PABLO CASALS)

SCHWARTZ: Phonograph records are one of the most poignant ways to keep human things alive. If the habit of remembering the past is lost, we ourselves will in turn be forgotten.

I'd like to read an old poem of mine. It's a kind of testament to those recordings I continue to treasure so much. It's dedicated to my friend, the poet Frank Bidart, who loves these old records at least as much as I do.

Seventy-Eights.

Breakable, heavy, clumsy,

The end of a side, the middle of a movement or phrase,

The faults are obvious.

Surface noise, one opera, three albums, four inches,

Thirty-three sides wide.

But under the noise, the surface,

The elegant labels, the bright shellac,

Revolutions.

Sagetti, Schnabel, Busch (ph), Beecham, Casals,

Toscanini, new '30s disk star at 60.

All their overtones

Understood, amplified, at hand.

Our masters' voices taking our breath,

Revelations per minute,

Winding up in a living room,

Turning the tables, taking off,

Moving, moving faster, they make us think,

Than the speed of death.

GROSS: Lloyd Schwartz is classical music critic for "The Boston Phoenix."

FRESH AIR's executive producer is Danny Miller. Our Writers' Week series is produced by Kathy Wolfe (ph). Our engineer is Chris Fraley (ph). Dorothy Ferebee is our administrative assistant. Roberta Shorrock directs the show.

I'm Terry Gross.

(AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, OPERA ARIA, MARIA CALLAS)

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia, PA

Guest: Lloyd Schwartz

High: Classical music critic Lloyd Schwartz tells us what music he most wants to remember from the 20th century, including selections from the new box set "Stravinsky Conducting Stravinsky," "The Dvorak Cello Concerto with Pablo Casals," Joseph Szigeti's "Prokofiev Concerto," Artur Schnabel on a currently out-of-print Schubert CD, and Maria Callas's recordings.

Spec: Entertainment; Music Industry; Profiles

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1999 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1999 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: 20th Century Music To Remember

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.