The World According to Willie

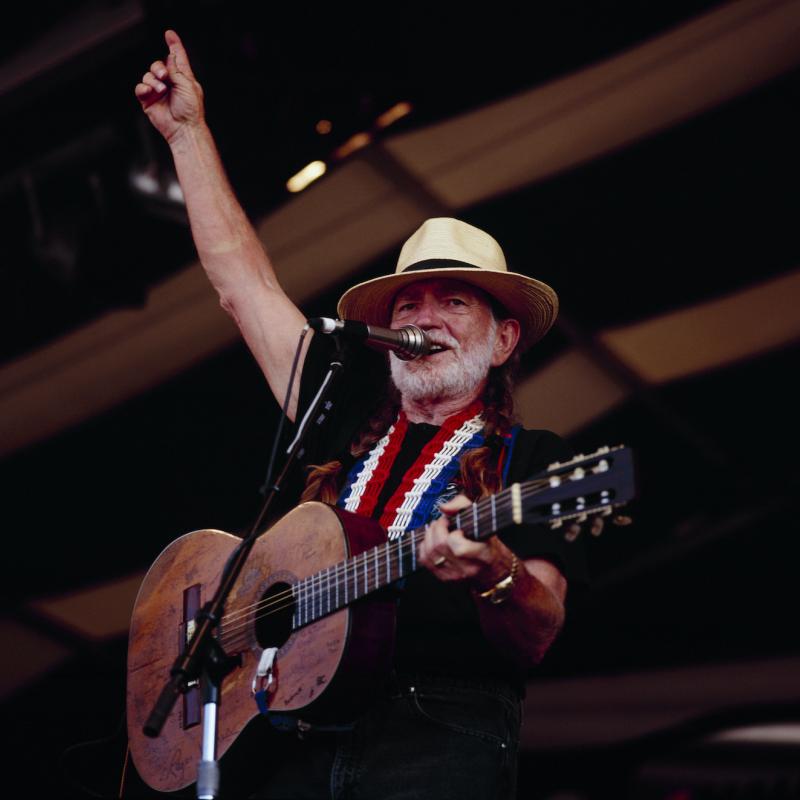

Country music singer and songwriter Willie Nelson's newest book is The Tao of Willie: A Guide to the Happiness in Your Heart. Nelson, who has been performing for more than 50 years, has recorded 250 albums and appeared in 25 films. (Original airdate: 5/25/06)

Other segments from the episode on September 4, 2006

Transcript

DATE September 4, 2006 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: James Hand speaks of his life, career, and new CD

"The Truth Will Set You Free"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Today we're concluding our holiday weekend series of country music interviews.

Later in the show, we'll hear from the great Willie Nelson. But first, a

singer and songwriter Nelson calls "the real deal," James Hand. The

53-year-old has performed mostly in local bars near the small town in Texas

where he lives, but this year Rounder released his first CD, "The Truth Will

Set You Free." A review in the Austin Chronicle described Hand as singing

dark, world weary songs in a suffering wail of a voice filled with pain and

wonder. Before we get to the suffering songs, let's start with something a

little more upbeat. This is "Banks of the Brazos."

(Soundbite of "Banks of the Brazos")

Mr. JAMES HAND: (Singing)

On the banks of the Brazos

now that's where love has us

And that's where I'm going

just as soon as I can.

Her love for me is strong

and in her arms I'm belonging

Out on the banks of the Brazos

with her love, hand in hand.

For so long I've been yearning

but I find strength in learning

That she waits for me

and so deep in love are we

That forever we will be

on the Brazos, hand in hand.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's James Hand from his new CD, "The Truth Will Set You Free."

James Hand, welcome to FRESH AIR. Tell us about the song we just heard.

Mr. HAND: Well, "The Banks of the Brazos," I used to live up there on the

banks of the Brazos, and one little gal that lived on the river there, and I

heard it so much I just wrote a song about it and, you know, everyone kids me

about writing three chord country songs, well, that one there--I don't know if

I wrote it because I liked the sound of the river, because I just knew eight

or 10 chords at that particular time. But thank you for playing it.

GROSS: Well, you know, James Hand, I'm certainly glad you started recording.

You're in your mid-50s now. And this is your first like really nationally

released CD. I think it's really terrific. Did you think it was too late and

that your chance to have a real recording career was over before you were

approached to do--right before you were approached to do this record?

Mr. HAND: That's a good question and a difficult one to answer. I don't

think there's any way that I could have done what I'm doing as little as four

years ago. And I live in mortal fear of someone telling me, `You know what,

James? You sang a lot better five years ago.' Well, I might have sang better,

but I certainly wasn't at peace with anything, and I'm not at much at peace

with myself at anytime, but I'm more so now than I was then. You know, some

people say it's too late, and some people say it's too early, just as some

people pray for water and some people dig a well. So it's...

GROSS: Did you know that you were good? And did you know that you were good

even though you didn't have like a real music career? Or did that kill your

confidence, you know, not having albums, not performing in big venues?

Mr. HAND: Well, as a child--and this will really relay my rural

upbringing--we had a cistern. I don't know if you know what a cistern is. It

catches water off the roof. And before I had any knowledge of what I was

doing, I would go there and I would stick my little head in that cistern and

holler and scream, you know, just so I could hear the reverb of it. And I

cried as a child when I would hear certain songs and didn't even know what

they were about. You know, sometimes it's like being cursed or haunted, and

then it's not there and you wonder where it went, and you pray to God to hurt

again. That's how it feels for me sometimes.

GROSS: What songs made you cry when you were young?

Mr. HAND: Oh, like "Green Grow the Lilacs" and, you know, Tex Ritter songs

and sometimes even classical music. You know, you just hear the music. It

was--it started out I would hear these voices in my head and, you know, mom

and daddy was gone rodeoing a lot, and my grandmother, she, you know, she told

me that it was God. And it probably was, but, you know, seven- or

eight-year-old, six-year-old child has a hard time comprehending that. But I

know this for a fact, she saved the Big Chief notepads I'd scribble little

words or rhymes down in.

GROSS: Do you remember writing your first song?

Mr. HAND: Yes, I do. I mean, the first one that really mattered anything,

and it's on a previous album of mine. I wrote it when I was 15 years old in

high school. We got time for just maybe a little verse of it here. It's

called "Merry Christmas, Darlin'."

(Singing)

Merry Christmas to you, darlin' from your old used-to-be.

Did you see the card and the gift I put beneath your tree?

Did you know who sent them even though no name was signed?

Merry Christmas, darlin', from this broken heart of mine.

GROSS: Oh, that's great. Did you have a girlfriend you were writing it to?

Mr. HAND: Well, yes, ma'am. I was 15 and--Pam, I hope you're not mad at

this, but they ask me things about my past.

GROSS: That's James Hand, and his new CD is called "The Truth Will Set You

Free."

Now, you grew up in a really small town in Texas.

Mr. HAND: Yes, ma'am.

GROSS: How small?

Mr. HAND: Everybody that lives in it can tear the phone book in half. It's

about 2500 people, I think, a little town called West. It's 90 miles south of

Dallas, and it's 18 miles north of Waco. And it's right there on Interstate

35. And to really put a geographical location on where I actually live, it's

about three miles west of West. There's a little town out there called Tokio.

Now, it use to be a railroad depot, but back in the war they changed the

spelling of it to T-O-K-I-O instead of T-O-K-Y-O. And that's where we, you

know, we--my brothers, my family and I, we were raised there. And I think in

the high school, there were less than 300 people in the high school.

Now, of course, it's grown some now but it's still--it's a community where

everybody knows everybody. And in spite of what all you hear about the gossip

things and the gossip and that, it's a wonderful place. And it's like

anything. It's, you know, there's always going to be roses and there's going

to be rose fertilizer. Hopefully, if you've walked through the rose

fertilizer you don't track it in on the carpet.

GROSS: What has your music career been like? I know you've made a living

doing several things over the years--bouncer, truck driver, horse trainer.

I'm sure you've also, you know, played, you know, a lot of bars and stuff and

made money, too.

Mr. HAND: Yes, ma'am.

GROSS: But it sounds like you've always needed another job to support

yourself. So what was your music career like until this point? What kind of

places would you play?

Mr. HAND: Well, ma'am, if I were a script writer, which I'm not, I think the

life I've lived would lend itself to the back of any country album. Although,

I'm not proud of the life I've lived. I don't think that anyone should talk

about the bad over the good. But you're right, I have done a, you know, I've

done a lot of other things. And at this point in my life, I've explained to

people, this is what I've got to do. It's not what I've got to do because I

can't do anything else. It's just what I feel like I can do better than

anything else I can do. Not the best that someone else can do but the best

thing that I can do, you know, because it keeps me from going crazy and, you

know, literally. And it drives a lot of other people crazy that I don't like

a lot, so that--I've got a double-edged sword there, I think. But music, it

is wonderful.

GROSS: You know, you just said that music keeps you from going crazy,

literally. You know, and earlier you said that, when you were a child, you

heard voices. And so I'm wondering like how literally do you mean? I mean,

did you ever think you were literally going crazy and did you hear voices that

made you think that you were going crazy?

Mr. HAND: Well, whenever I thought I was really going crazy, I heard voices

all right, but it was like, you know, it was angels or, you know, just saying

don't do that. I, you know, you're a nice lady so I'll give you a straight up

answer on it. I use to see myself on the mirror turning into a werewolf.

Well, I'd start praying, and I'd turn back to me. Now, I'm no theologian, or

however you say that, but if you don't think something's right behind you that

is going to do you harm, then you're wrong. And, as they say, a rut is

nothing but a grave with both ends kicked out of it. And you stay in it long

enough and it'll get kicked in on you. I've done some things that I'm not

particularly proud of. I've stepped off the page a time or two, but we all

do.

GROSS: My guest is James Hand. His album is called "The Truth Will Set You

Free." We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: Let's get back to our interview with James Hand. The 53-year-old

singer and songwriter's first album, "The Truth Will Set You Free," was

released earlier this year.

Do you go to church? And I'm wondering if you sing, you know, hymns and

spirituals, gospel songs.

Mr. HAND: Well, yes, ma'am. I don't go--I don't go to church as often as I

probably ought to, but I carry church in my heart. And I write quite a--I

write a lot of gospel songs. As a matter of fact, there's one on the album

that--"If I Live Long Enough to Heal." You know, a lot of folks things it's

about a man with a broken heart, but it ain't. It's about a man watching his

daddy die.

GROSS: Would you sing a little bit of that for us?

Mr. HAND: Why, sure.

(Singing)

I'm getting well,

I can tell, day by day.

God reaches down, pulls me up

and helps me along my way,

He holds my hand

and, understand, his love so true to me

And there is no doubt

he'll lead me out if I live long enough to heal.

If I live long enough,

my way won't be so rough

And then perhaps I'll be

proud and strong, not always wrong

and finally to be free

Lord, I'll be straight and tall,

not afraid at all, and then what can sorrow steal?

And there is no doubt, he'll lead me out

if I live long enough to heal.

GROSS: Thank you for doing that. That's James Hand performing in the studio.

Mr. HAND: Well, thank you.

GROSS: And it's a song that he also sings on his new CD, which is called "The

Truth Will Set You Free," and it's his debut nationally released CD.

You know, there's a certain haunted quality in some of your songs, and I'm

wondering if that comes in part by the kind of feelings that you were just

describing. And one song like that that I'm thinking of is "Shadows Where the

Magic Was."

Mr. HAND: Mm-hmm. That--it's nearly true. I didn't stay in there. At the

end of the song, you know, I...

GROSS: Why don't we explain? This is about somebody who goes to his old

home...

Mr. HAND: Right.

GROSS: ...and now it's surrounded by malls and stuff.

Mr. HAND: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: But that area still has--well,l you take it from there. You explain

it.

Mr. HAND: OK, it's, I mean, I don't have to be vague about it. I did write

that song, and I was in that house, and I was drunk. But I didn't stay there

to, you know--I mean, obviously not or I couldn't have written a song. But...

GROSS: Because at the end of the song the guy burns the house down and

himself with it.

Mr. HAND: And he just stays there.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. HAND: But I think that that's probably one of the absolute best songs

I've ever written because I--the story of it, the way he goes and just every

little step he takes, he knows he ain't coming back. And when you look at

something and you don't see a face, well, that's death. But through the grace

of God and some very dear friends of mine, everything I look at now I see a

face.

GROSS: What was the house that the song was about?

Mr. HAND: It was a house where--it was a just a--it was a bad place to be.

GROSS: Well, let's hear this song. This is "Shadows Where the Magic Was,"

and it's by James Hand from his new debut CD, "The Truth Will Set Your Free."

(Soundbite of "Shadows Where the Magic Was")

Mr. HAND: (Singing)

I drove through the town

and I found the street and the block where we once lived.

I had to make my misery complete

and see if I could take what life could give.

I walked through the gate,

and I rushed through them doors

And just about to fall,

The wind grew still and my blood ran cold

and the hair on my neck began to crawl.

There are shadows where the magic was

and there's darkness all around,

Now who can tell what the devil does

when he walks on haunted ground.

All around the old place

where my children played...

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: You said that, you know, you've taken some wrong turns in your life.

Mr. HAND: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

GROSS: I imagine one of those wrong turns you were arrested for possessing

amphetamines and spent...

Mr. HAND: Yes, ma'am.

GROSS: ...I think, like nine months in prison.

Mr. HAND: Sure. Mm-hmm.

GROSS: Was that a really bad experience for you or did anything good come out

of that?

Mr. HAND: I'll put it like this, when I got out I never went back. So I

think that if a fellow wants to do something, he's going to do it. And if he

don't want to do it, he's not going to do it. I couldn't have--I just

couldn't stand to hurt my parents or my family anymore, and it never occurred

to me. I mean, I read about myself all the time about drinking and drugs and

all this kind of stuff, and there are people in this business that play that

up. They want everybody, `Oh, man, I did this and I did that.' Well, I want

to tell you a little story about that. Everybody wants to know an outlaw, but

nobody wants to be an outlaw. If a guy has got a problem, he's not going to

wear it on his sleeve because he don't want anybody to know. If he's an

outlaw, he's not going to tell anybody because he don't want anybody to know.

The louder people say that they had a drug problem or they went to prison or

they were an outlaw or they did this, the louder they say that, the less they

probably did it and the less anybody with any kind of class at all wants to

hear it. Now, if someone asks me about it, I'll be forthright and honest

about it. Yes. But if somebody doesn't ask me about it, I don't call around

to publicists to say, `Hey, guess what?'

GROSS: Yeah, `Play this up.'

Mr. HAND: Yeah, `Play this up because I went to prison and broke everybody's

heart in my family and a lot of my best friends.' You know?

GROSS: You're in your mid-50s now. Your first real album has just come out.

Mr. HAND: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: So this could be a real turning point in your life. Are there things

that you want now musically or from the rest of your life that you are hoping

that this CD will help you achieve? I mean, are there changes that you really

want to make? Is there--are there things that you want?

Mr. HAND: If you're talking about monetary gain, I would like to be able to

do things for my family. I'd like to do things for my friends. I'd like to

be somewhat of a success. And money is like 180 miles an hour on the

speedometer, it's there if you need it, not just to use it all the time, but

if you don't have it then you worry about it.

Now, as far as the--any other success, I want to be honorable and be honorable

in the eyes of everyone. And that's hard to do sometimes because we all slip

from the page. Now this CD, I think it surprised Rounder. I don't think they

thought it was going to do anything at all, and I've been very blessed by that

and blessed by speaking to you. And I hope the folks understand that I ain't

nothing no more than nobody else. I just want to have a chance to say

something, not everybody think I didn't do nothing.

GROSS: Well, I want to thank you very much for talking with us.

Mr. HAND: Well, it's my honor. Thank you, Terry.

GROSS: James Hand, recorded earlier this summer. His new album is called

"The Truth Will Set You Free." I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of song)

Mr. HAND: (Singing)

There are times I know just who I am

and what I want to be

Till the raging river climbs the dam

to come crashing down on me.

Then all at once I find myself

in a wild and angry sea

And everything I thought I might have had left

is laughing back at me.

You're just an old man

with an old song

A cold hand and now your game is gone.

I can't understand

what's took you so long

to see you're just an old man with an old song.

(End of soundbite)

(Announcements)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Willie Nelson discusses his life and career

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

We're concluding our holiday weekend series of country music interviews with

Willie Nelson. He's famous for many things, from writing songs like "Crazy,"

"Night Life," "Hello Walls," and "Funny How Time Slips Away," to organizing

Farm Aid and touring on his bus powered by biofuels. This summer three of his

albums from the '70s--"Shotgun Willie," "Phases and Stages" and "Live at the

Texas Opry House"--were released in a set called "The Complete Atlantic

Sessions." From "Shotgun Willie," here's "Local Memory."

(Soundbite from Willie Nelson's "Local Memory")

Mr. WILLIE NELSON: (Singing)

The lights go out each evening at eleven,

and up and down our block, there's not a sound.

I close my eyes and search for peaceful slumber,

and just then the local mem'ry comes around.

Piles of blues against the door

make sure sleep will come no more.

She's the hardest working mem'ry in this town,

Turns out happiness again,

and lets loneliness back in,

and each night the local mem'ry comes around.

Each day I say tonight I may escape her.

I pretend I'm happy and never even frown.

But at night I close my eyes and pray sleep finds me,

but again the local mem'ry comes around.

Rids the house of all good news,

then sets out my crying shoes,

What a faithful mem'ry never lets me down.

We're both up till light of day,

chasing happiness away.

And each night the local mem'ry comes around.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: I spoke with Willie Nelson in May after the publication of his book

"The Tao of Willie." He's a friend of singer and songwriter Billy Joe Shaver,

who we featured in our country music series on Friday. In that interview,

Shaver described a time when Willie Nelson just about saved his life.

Shaver's son had just died of a heroin overdose. Shaver said his son had

fallen in with a bad crowd, but it's unclear what happened the day he died. I

played Willie Nelson the part of that interview in which Shaver described that

day and what it was like after the police took him to the hospital where his

son was.

Mr. BILLY JOE SHAVER: I don't know what happened. I really still to this

day don't know what happened, and I tried to stay in there with him while they

were checking him to see if he was brain dead, and the police ran me off and

they wouldn't let me back in. Told me they were going to arrest me. Oh, my

God! And Willie Nelson, now, I've got to give him credit, he's the one that

talked me back out into the world. He said, `Come on, Billy.' He says,

`You're supposed to play tonight. It's New Year's night.' He said, `I'll

throw something together.' And Willie stayed up there and played all night

long, and I'd go up and sing every once in a while.

I owe Willie a lot. He's been such a good friend. And he took me down to his

house, and we spent the night there and hadn't talked in quite a long time.

And he told me a lot of things because he knew a lot. He's a wise man, and he

gave me some money. And you know it's hard being broke when you're in a

situation like that, and then he paid for my son's burial. I didn't have any

money at the time.

GROSS: So that...

Mr. SHAVER: I later got some money from Sony and tried to pay him back, and

he wouldn't take it.

GROSS: That was Billy Joe Shaver on FRESH AIR, the songwriter and singer.

And my guest is Willie Nelson.

And, Willie Nelson, when Billy Joe Shaver told that story, and he talked about

how on the day his son died, you got together a band and basically forced him

to perform that night, it made me wonder if part of the reason that you did

that was because you thought that the stage was the only safe place for him

that night, because it sounds like he was so upset about his son's death that

he might have, like, drunk himself into a bad place or done something, taken

some action that he might have lived to regret.

Mr. NELSON: Well, I always find that on the stage is the safest place for

me, no matter what I've been in to. If I get up there for a couple of hours,

I can sometimes work it out. Most of the time during the show I can sort of

clear my mind of whatever. So I knew that at this particular time Billy Joe

needed to be working. This wasn't a good time to be laying around thinking

about things.

GROSS: So how do you put together a concert? On the night of his son's

death--I mean, what kind of music seemed appropriate for him and for you? I

don't know if you even remember.

Mr. NELSON: Oh, I do remember very well, and it wasn't--the music itself

wasn't anything out of the ordinary. I did some of my songs, and then

occasionally Billy Joe would come up and do one of his, but it was mainly the

fact that we were out there, we were at this club, and we were trying to make

the best of a really bad situation. And I figured that that was the best way

that I could help Billy Joe was just to get him back on the stage, singing and

playing and sort of living in the moment again and forgetting about what just

happened, if he could.

GROSS: Did the audience know what had happened?

Mr. NELSON: I think most everyone there knew what had happened, and they

were all, you know, happy to see Billy Joe there because they also knew that

this was where he needed to be, out with friends, fans, rather than trying to

hole up somewhere.

GROSS: I figure you must have known something about what Billy Joe Shaver was

going through because you lost a son, too. Did you perform after that? Did

the stage seem like the best place for you?

Mr. NELSON: Yeah, right after my son died, I had a gig booked in Branson,

Missouri, and it was around New Year's Eve, and he died on Christmas. So it

would have been real easy for me to cancel and go off somewhere and, you know,

grieve alone somewhere for months or a long time. I could have done it. It

was--it would have been the easiest thing to do. But I didn't. I just knew

instinctively that my best place to be was somewhere on the stage. And it

just so happens that I had a six-month gig there in Branson, Missouri, so I

had six months, and I think it was the best place for me, especially at that

time.

GROSS: You have so many great records, it was really hard to narrow down what

songs I wanted to play during your FRESH AIR visit today, but here's one I

know I want to play. There's a great album that came out, oh, about three

years ago called "Crazy: The Demo Sessions," and it's demo recordings that

you made after you were a DJ.

Mr. NELSON: Right.

GROSS: When you got to Nashville, and these are--some of them are from the

early 1960s. This one is. It's from 1961, and the song is called

"Opportunity to Cry." It's just voice and guitar. Do you remember making

this?

Mr. NELSON: Sure. Was this the cut that we did in Nashville? Or is this a

later cut?

GROSS: Well, you know, on the liner notes, I think it says that all they know

is that--they think it's recorded in your office.

Mr. NELSON: It probably was because I did a lot of recording downtown--or

not--actually it was out in Goodlettsville, out of a place called Pampered

Music, where the publishing company was. And I did a lot of writing and

playing, sitting around in a garage back there that had been converted into a

studio. So that's probably where I was.

GROSS: OK. Well, let's hear it. This is Willie Nelson, recorded in 1961.

It's a demo of his song "Opportunity to Cry."

(Soundbite of "Opportunity to Cry" by Willie Nelson)

Mr. NELSON: (Singing)

Just watched the sun rise on the other side of town.

Once more I've waited and once more you've let me down.

This would be a perfect time for me to die.

I'd like to take this opportunity to cry.

You gave your word, now I'll return it to you

with this suggestion as to what you can do.

Just exchange the words `I love you' to `Goodbye'

while I take this opportunity to cry.

I'd like to see you, but I'm afraid that I...

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: That's Willie Nelson and a demo recording he made of his own song in

1961 when he was trying to interest people in recording his songs.

What was the fate of that song? Did anybody ever do it?

Mr. NELSON: I don't think everybody--anybody done it but me. I've recorded

it maybe a couple of times since then on, you know, various, a couple a

different albums. I don't remember what they were right at the moment, but it

was one of those really sad, almost pitiful songs.

GROSS: You know, in talking about country songs, like country songs have

certain conventions in a way. You know, a lot of country songs are about

cheating or drinking too much or falling in love. I guess you could say the

same thing about rock songs, but there's also like a subcategory of country

songs where like you're feeling so bad, you're just overwhelmed with

self-pity, and one of the most self-pitying of the self-pitying songs is a

song that you wrote that's included on your demo sessions that I really want

to play and hear the story behind, and so here it comes. This is Willie

Nelson singing a very self-pitying song.

(Soundbite of a Willie Nelson song)

Mr. NELSON: (Singing)

If I'd only had one arm to hold you,

better yet if I'd had none at all.

Then I wouldn't have two arms that ache for you,

and there'd be one less memory to recall.

If I'd only had one ear...

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: And then in the next verse, you imagine only having one eye, so you'd

have only one eye to cry. Did you think...

Mr. NELSON: That's pitiful, isn't it?

GROSS: Yes, so self-pitying. Did you think that, when you sat down to write

this, that you would write the ultimate self-pitying song?

Mr. NELSON: Actually, I didn't sit down to write that one. The way that

song happened, I was lying in bed with Shirley, and I woke up in the middle of

the night wanting a cigarette and her head was on my arm, so I had to reach

over on the side of the bed and get a cigarette and put it in my mouth and

then get a match with that one hand and then try to strike that one match. So

it all started from that.

GROSS: Oh, because you only had one arm. Really? Is this really what

happened?

Mr. NELSON: That's true. That's a true story. So from the one arm, I went

into the one eye, one ear, one leg.

GROSS: That's really funny. And what was the fate of this song?

Mr. NELSON: I recorded it a couple of times. Other people have recorded it.

Merle Haggard recorded it, I think. George Jones did. So it's got a pretty

good history.

GROSS: My guest is Willie Nelson. We'll talk more after a break. This is

FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: Let's get back to our interview with singer and songwriter Willie

Nelson. This summer three of his albums from the '70s were released in the

set called "The Complete Atlantic Sessions." From one of those records, "Live

at the Texas Opry House," here's a song he co-wrote with Waylon Jennings,

"Good Hearted Woman."

(Soundbite of "Good Hearted Woman")

Mr. NELSON: (Singing)

Well, a long time forgotten

her dreams that just fell by the way

And the good life he promised

ain't what she's living today

But she never complains

of the bad times or the bad things he done

She just talks about the good times

they've had and all the good times to come

She's a good hearted woman

in love with a good timin' man

She loves him in spite of his ways

that she don't understand

And through teardrops and laughter

they're going to pass through this world hand in hand

This good hearted woman

in love with a good timin' man

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: In your new book, "The Tao of Willie," you write in praise of

marijuana. You write, "The highest killer on the planet is stress, and there

aren't many people in America who don't medicate themselves one way or

another. Some people choose an occasional beer or a little pill the doctor

prescribes, and I'm not knocking that, but the best medicine for stress is

pot." Then you go on to say that alcohol and a lot of prescription drugs don't

agree with you but marijuana does. Are you afraid to talk that way, afraid

that, like, you'll be busted.

Mr. NELSON: Oh, I have been busted, more than once, you know. It's just,

minor amounts, so, a fine, whatever. It's--there was a time, though, when,

especially in the state of Texas when a couple of C's could get you life. But

things have lightened up a little bit. You have people out there who are

sharper, now who realize that there's a slight difference between marijuana

and heroin. But the fact that you can use it for fuel--I drove a Cadillac

across Kentucky one time on hemp oil.

GROSS: You're full of surprises when it comes to biofuels. So what are you

driving with now?

Mr. NELSON: I think we're driving soybeans right now. I think we buy

biodiesel wherever we can find it, and usually most of the biodiesel that we

find is made from soybeans.

GROSS: How did you start doing that? Like using alternative fuel?

Mr. NELSON: My...

GROSS: It's become one of the things that you're famous for.

Mr. NELSON: It hasn't been that long ago, maybe three years ago, my wife

came to me and said, `I want to buy this car that runs on biodiesel,' and I

said, `What the hell is that?' And she said, `Well, it's vegetable oil.' And I

thought she was--you know, been on that Maui-wowie again, you know. So I

said--I said, `You better make sure you're right on this one.' She bought a

brand-new Volkswagen Jetta. She--there's a business on Maui and has been for

many years now where they go around to all the restaurants and they collect

the grease from the grease traps and they recycle it and turn it back into 100

percent pure vegetable oil, and you can put it right into your diesel car. So

she bought her car, I drove it, the tailpipe smelled like french fries. I

said, `Wait a minute. We may be onto something here.'

So I bought a Mercedes, a brand-new one, and I filled it right up with

vegetable oil, and I think the Mercedes people shuddered a little bit when

they first heard about that because they wasn't sure themselves what this

would do to their $60,000 automobile, but it has run perfectly, it runs

cleaner, I get better gas mileage. You know, the president said we're

addicted to oil. I don't think we're addicted. I just think that's the only

thing we have had. So we're glad to find alternatives. So along with ethanol

biodiesel, your hydrogen, your windmills, all these different ways of making

fuel combined, will help us reduce our dependency on foreign oil.

GROSS: Now, in your new book, "The Tao of Willie," you say that you wrote

your first cheating song when you were seven, long before you knew firsthand

anything about broken hearts and cheating. When you started writing songs

when you were older, did you know anything about like the structure of a

32-bar song or what a bridge was like? You know, how to write the bridge to a

song. Did you think of a song in technical terms when you started seriously

writing them?

Mr. NELSON: No, I never did. And I still really don't. I just kind of

write and sing of what I feel like writing. And my timing is pretty good, so,

you know, I don't break meter that much. And my ear is pretty good so I don't

play a lot of wrong chords. But, you know, as far as the lyrics and the

singing itself, everybody has to judge that for themselves. But back in those

days, I was writing about things I had, you know, like you say, at that I

couldn't have possibly have known what I was writing about, unless you happen

to believe in reincarnation, which I do. And I probably come here knowing

some things that I wrote about before I knew I knew.

GROSS: My guest is Willie Nelson. We'll talk more after a break. This is

FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: We're listening back to an interview with Willie Nelson. I asked him

about his friendship with Johnny Cash. They performed together in the group

The Highwaymen.

How would you describe him as a friend?

Mr. NELSON: Well, a friend is a friend. You know, a friend is with you good

or bad, anytime, so John and I have always been friends. And whenever--you

know, he'd call me up several times when he was having a bad day just to hear

a joke, and so I'd tell him my latest dirty joke, and I'd try to make it as

dirty as possible so he would laugh louder.

GROSS: You actually must collect jokes or something because like your new

book, for instance, is filled with jokes, literally jokes.

Mr. NELSON: Well, I believe in jokes, you know. I think jokes are

important, a necessity. You need to laugh at yourself, other people, life,

death. You need to figure out a way to laugh at everything.

GROSS: Do you tell a lot of jokes onstage?

Mr. NELSON: No, I don't tell any jokes onstage.

GROSS: How come?

Mr. NELSON: I'm afraid that if I quit singing, people will leave. I don't

think they came to hear me tell jokes.

GROSS: That's funny. Did someone in your family tell jokes when you were

growing up.

Mr. NELSON: Yeah, that was, you know, that was our entertainment. That was

before TV. We'd just sit around and tell jokes to each other and play dominos

and tell more jokes and play dominos.

GROSS: And sing too?

Mr. NELSON: And sing, yeah.

GROSS: Did the family sing together?

Mr. NELSON: Oh, yeah. My grandfather was a great singer, and my grandmother

sang. My mother and dad were both singers, too. But I sang quite a bit in my

early life with my sister. We played guitar and piano, and I would sing.

My--but, you know, my grandfather died when I was six years old. So after

that, we'd sit around and play piano, and my grandmother would teach sister

how to play the piano. And I'd sit there on the piano stool and try to learn

the chords along with her as she was reading the music.

GROSS: I want to ask you a little bit. You know, your new book is called

"The Tao of Willie," referring to the "Tao Te Ching," which is, you know, an

ancient book of Chinese wisdom. I think the first song that you ever sold was

"The Family Bible." Do I have that right?

Mr. NELSON: Right. Right.

GROSS: So, you know, the Bible has literally played a role in your

songwriting career. What kind of role did it play, like, in your home when

you were growing up?

Mr. NELSON: Oh, you know, it was a great role that it played. My

grandparents were huge gospel singers and writers, and they--Sunday School

teachers and they, you know, always had gospel music, singing it and playing

it, listening to it on the radio, singing it in church. And the Bible was

there, and it was read all the time. I turned--I was a Sunday School teacher,

so I, you know, started reading the Bible more and more and teaching it in

class. So, yeah, I grew up reading the Bible.

GROSS: How did you start reading books of Chinese wisdom and start

meditating?

Mr. NELSON: One of the things that I was wondering about in--when I was

going to church and teaching Sunday School was I knew that I was a Christian,

but I knew that there was millions of people out there who were other

religions, and I wanted to find out about those other religions, so I did a

lot of research in the Bible. And that was about--I mean, in the library and

read about different religions. I read about all the religions I could find

and also read things by Kahlil Gibran and Edgar Cayce, and they talked about

reincarnation. And it made so much sense to me to believe that, you know,

this one time through, there's no way you could get it right. It's kind of

like going to school. You pass the first grade, you go to the second grade,

and I--you know, I'm probably somewhere around the fourth grade, right now,

still coming back, and so I believe that's the only thing that makes sense is

you do get a chance to come back. It's not a chance, you are forced to come

back and learn the lessons that you didn't learn the last time.

GROSS: Let me bring this back to your songwriting. When you write songs, are

you sitting down and working in a craftman--craftsman-like way on a song or

are they just kind of coming to you while you're doing things?

Mr. NELSON: It used to when I was driving myself to different gigs around

the country, I would do a lot of writing just driving down the highway. And I

still think, you know, that that's the best way for me to write. I can get in

the car, I believe, and take off driving and head anywhere and start thinking

about something, and, if I'm lucky, I'll write a song, but I have to get

somewhere by myself to do it. There's a lot of things going on, a lot of

interruptions and things, that makes it difficult to do and just, you know,

riding the bus.

GROSS: And what about writing the music part, like the chords for instance.

Do you need a piano or a guitar when you do that?

Mr. NELSON: If there's a guitar or piano around, I would use it, but I can

usually write it all in my head, and then I'll get a guitar when I find one

and go over the lyrics and the melodies and probably wind up changing it

several times before I finally decide this is the way I want it.

GROSS: But from what you said before, it sounds like--I mean, do you ever

like actually write it down?

Mr. NELSON: I do now more than I used to. I used to have this theory that,

`Well, if you don't remember it, it ain't worth remembering,' but later on in

life, I figured out, `Well, maybe I--maybe I should jot down this one because

I don't want to forget it.'

GROSS: Willie Nelson, it's been a pleasure to talk with you. Thank you very

much.

Mr. NELSON: Well, thank you. It's nice to talk to you again.

GROSS: Willie Nelson recorded in May after the publication of his book "The

Tao of Willie." Three of his albums from the '70s are now out in a set called

"The Complete Atlantic Sessions."

(Soundbite of song)

Mr. NELSON: (Singing)

You told me once that you were mine alone forever

and I was yours till the end of eternity

But all those vows are broken now and I will never

be the same except in memory

Remember me when the candlelights are gleaming

Remember me at the close of a long, long day

And it will be so sweet when all alone I'm dreaming

just to know you still remember me

(Credits

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.