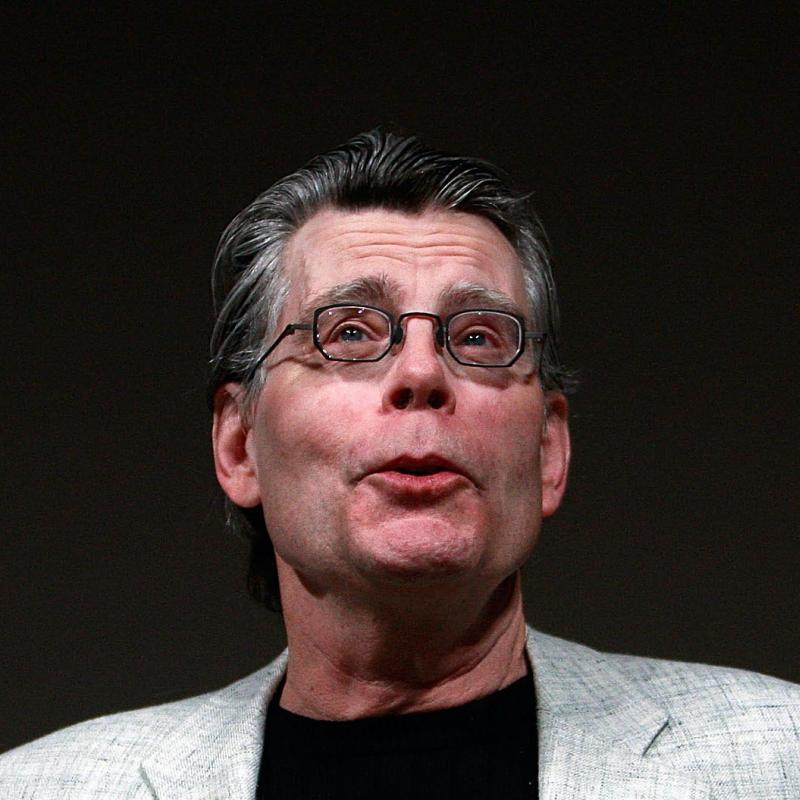

Stephen King "On Writing."

Novelist Stephen King. Last year, the prolific and popular horror writer experienced something that could have come out of one of his books: he was struck by a car while walking along a rural road in Maine and nearly killed. Six operations and a long recovery followed. Five weeks after the accident King started writing again, and published over the internet only, the novella, “The Plant.” His new book is “On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft” (Scribner).

Other segments from the episode on October 10, 2000

Transcript

DATE October 10, 2000 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Stephen King discusses his career and recovery from

injuries sustained after being hit by a van last year

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

My guest, Stephen King, was nearly killed in June of last year while taking

his daily walk. He was walking along the gravel shoulder of Route 5, a

two-lane highway near his home in Maine, when he was struck by a van driven by

Bryan Smith, who had several prior convictions for speeding and reckless

driving. Last month Smith was found dead in his home. The autopsy wasn't

conclusive. The results of toxicology tests are expected to take several

months.

King is still recovering from his injuries, which included nine breaks in his

right leg; his right knee split almost directly down the middle; a fracture of

his right hip; four broken ribs and a scalp laceration that required nearly 30

stitches. His spine was chipped in eight places. Yet he's still writing, and

he's made news for the way he's used the Internet to publish recent work.

1is new book is a real book, not a virtual one. It's called "On Writing,"

and it's part memoir, part reflections on his craft. The last chapter is

about his accident. Let's start with a reading.

Mr. STEPHEN KING (Author): (Reading) `Most of the sight lines along the mile

of Route 5, which I walk, are good. But there is one stretch, a short, steep

hill, where a pedestrian walking north can see very little of what might be

coming his way. I was three-quarters of the way up this hill when Bryan

Smith, the owner and operator of the Dodge van, came over the crest. He

wasn't on the road. He was on the shoulder--my shoulder. I had perhaps

three-quarters of a second to register this. It was just time enough to

think, "My God, I'm going to be hit by a school bus." I started to turn to my

left.

There is a break in my memory here. On the other side of it, I'm on the

ground looking at the back of the van, which is now pulled off the road and

tilted to one side. This recollection is very clear and very sharp, more like

a snapshot than a memory. There is dust around the van's tail lights. The

license plate and the back windows are dirty. I register these things with no

thought that I had been in an accident or of anything else. It's a snapshot,

that's all. I'm not thinking. My head has been swabbed clean.

There's another little break in my memory here, and then I am very carefully

wiping palmfuls of blood out of my eyes with my left hand. When my eyes are

reasonably clear, I look around and see a man sitting on a nearby rock. He

has a cane drawn across his lap. This is Bryan Smith, 42 years of age, the

man who hit me with his van. Smith has got quite the driving record. He has

racked up nearly a dozen vehicle-related offenses.

Smith wasn't looking at the road on the afternoon our lives came together

because his Rottweiler had jumped from the very rear of his van into the

backseat area, where there was an Igloo cooler with some meat stored inside.

The Rottweiler's name is Bullet. Smith has another Rottweiler at home; that

one is named Pistol. Bullet started to nose at the lid of the cooler. Smith

turned around and tried to push Bullet away. He was still looking at Bullet

and pushing his head away from the cooler when he came over the top of the

knoll; still looking and pushing when he struck me. Smith told friends later

than he'd thought he'd hit a small deer, until he noticed my bloody spectacles

lying on the front seat of his van. They were knocked from my face when I

tried to get out of Smith's way. The frames were bent and twisted, but the

lenses were unbroken. They are the lenses I'm wearing now, as I write this.

Smith sees I'm awake and tells me help is on the way. He speaks calmly, even

cheerily. His look, as he sits on his rock with his cane drawn across his

lap, is one of pleasant commiseration. "Ain't the two of us just had the

shittiest luck," it says. He and Bullet left the campground where they were

staying, he later tells an investigator, because he wanted some of those Mars

bars they have up to the store. When I hear this little detail some weeks

later, it occurs to me that I have nearly been killed by a character out of

one of my own novels. It's almost funny.'

GROSS: That's Stephen King reading from his new memoir, "On Writing."

Stephen King, welcome back to FRESH AIR. And it's so great to still have you

with us.

Mr. KING: It's nice to be here, but I tell people nowadays it's nice to be

anywhere.

GROSS: Right. Did Smith say anything else to you as you were laying there,

drifting in and out of consciousness, after he hit you?

Mr. KING: He said, `I've never had so much as a parking ticket in my life,

and here it is my bad luck to hit the best-selling writer in the world.' And

I think he said, `I loved all your movies.'

GROSS: Did he really say that?

Mr. KING: Yeah.

GROSS: So he's lying to you as you're lying there nearly dying?

Mr. KING: Well, he said he had never had so much as a parking ticket, and God

knows he had a lot of traffic offenses. We don't want to speak ill of the

dead if we can help it because he did die last month, on my birthday, as a

matter of fact, which was a little bit eerie.

GROSS: No.

Mr. KING: Yeah.

GROSS: Gee.

Mr. KING: He and I share the same middle name as well. We're both Edwins.

We were. Now I'm--well, never mind.

GROSS: You know, in that reading, you say that it made you think that he was

like a character in your fiction. Were there other things that made you think

of him that way?

Mr. KING: Well, God knows that I've lived in rural Maine for a lot of years.

It's where I grew up, and it's where my wife and I live now, in a town of

about 900 people. And we don't want to say that Bryan Smith is or was a type,

because I don't necessarily believe that there are types, but he had a certain

back-country quality with the Rottweiler dogs and the old van. And it's

really tough, Terry, to talk about Bryan Smith without making him sound like a

sort of Faulknerian stereotype, and so maybe I'd just as soon steer clear of

the whole issue. He was like a character in a Stephen King book, but only

because he seemed like a real Maine type to me.

GROSS: You were, understandably, really angry with the sentence that he was

given. He was basically given a suspended driver's license for a year. But

when he was found dead in his home toward the end of September, what was your

reaction to his death?

Mr. KING: Oh, I was shocked and I was sorry as well. When he hit me, Bryan

Smith was 42; when he died he was 43. And 43 isn't a natural span, I don't

believe, for a man in 21st century America.

GROSS: Did you feel like this was some kind of larger form of punishment or

that his death was related in any kind of larger way to this accident?

Mr. KING: No. I don't think that the world works that neatly, and I don't

think that justice is meted out by fate, or else people like Adolph Eichmann

wouldn't have lived so long, so well, before anybody caught up to them. And

God knows there are enough people, whose crimes would make anything that Bryan

Smith ever did look very small change in comparison, who have never been

punished at all.

My feeling about Bryan Smith was pretty simple. He had a very long record of

driving convictions and an even longer record--in the book I talk about the

dozen or so traffic convictions, but, in fact, he had been brought before the

courts on twice that many charges, where the charges were either dismissed or

under the seal of the court because he was a juvenile. These go back to the

time of his driver's permit.

And we're not dealing with somebody here who was a bad person or in the sense

that you'd want to see somebody sent to jail for robbery or murder or rape or

any of those things. Bryan Smith was just a bad, negligent driver, and I

wanted to see him not necessarily put in jail, but certainly put into a

situation where he'd be forced to consider the way that he was behaving, you

know, on a wide range of issues, from the way that he was driving and the way

that he was living.

GROSS: Stephen King is my guest, and he does have a new book that's called

"On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft."

Tell us about how you're feeling now, your ability to walk and all that.

Mr. KING: Well, the accident was in June of 1999, and I was totally

incapacitated at that point. If there was a bone on the right side of my

body, it was broken, with the exception of my head, which was only concussed.

And this is about 16 months down the line, and I'm able to walk fairly well.

I have a limp that I think is a lot more noticeable toward the end of the day

as things start to hurt more. I've continued to work rehab in order to

increase my range of motion. It doesn't seem to do a whole lot for some of

the pain issues that are centered around the hip, but most of the leg is

pretty pain-free now. And I'm grateful for that, and it's nice to be able to

walk at all.

The way it works: When you are in the hospital and you're stuck in bed, and

you've got various appliances attached to your body, you say to people, `Will

I ever get out of this bed?' And they say, `The chances are good.' And when

you get out of bed, you say, `Will I ever be able to bend my leg again?' And

they say, `The chances are good that you will. Most people do.' So that

continues to go on, `Will I walk again?'

And the last question, the one that I'm working on right now, as I said to the

doctor about--the orthopedist, David Brown(ph), who operated on my leg, I

said, `I'd really like to be able to play tennis. Will I be able to do that

maybe next summer?' And he said, `I think that the chances are fairly good

that you'll be able to run again and play tennis.' So nobody comes out and

says yes. They just tell you that the chances are good, I suppose, because

they don't want you to be depressed. But I'm walking, I'm thinking and I'm

really, really grateful to be alive.

GROSS: Do you need a walker or a cane, anything like that?

Mr. KING: No. I went from a wheelchair to a walker and walker to crutches

and two crutches to one crutch and put the last crutch aside in July, and I've

been walking unaided since then. My wife says that she's encouraged by the

trail of discarded appliances I've left behind.

GROSS: I'm glad you've left them behind. For your writing, you've had to

imagine people in extreme circumstances and imagine them in agony. Did your

accident feel like anything you had imagined for fiction?

Mr. KING: It all seemed familiar to me in the sense that there was nothing

involved with the whole deal that I didn't expect, but the odd thing is that

when you've been seriously hurt, there's a kind of numbing shock that sets in,

and as a result, everything is--there's no surprise involved with any of the

things that seem to go on. You just sort of--the things come and you deal

with them. It's like being cast adrift and riding the waves.

They took me to a hospital in western Maine and did a few things to me. They

took a look at the injuries and decided that they couldn't treat them there,

and they got a LifeFlight helicopter to take me to Central Maine Medical

Center in Lewiston. And while I was on the flight, my lung collapsed, and I

can remember one of the guys saying, `Oh, shit. We've got to do something

about this.' And I can remember the crackle of them unwrapping something and

somebody saying that they were going to stick me, and then I could breathe

again because they had intubated me and pumped up my lung again. And all of

this was just a sort of sense of, `Well, this is what's happening now.'

You become a totally passive person, in a way. You recognize immediately that

you've been seriously hurt and that you can't deal with your own life and that

you're going to have to depend on other people to pull you through, so you

just kind of let go. And that's pretty much the way that I always saw things

happening in my books, which doesn't surprise me that much because I think the

imagination--when you really use it at top quality, when you're seeing really

well, the imagination really knows what the reality is.

GROSS: My guest is Stephen King. His new book is called "On Writing: A

Memoir of the Craft." We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Stephen King is my guest. His new book is called "On Writing: A

Memoir of the Craft."

In an interview in Salon magazine before the accident, you said, `As a kid, my

mother used to say when we were scared, "Whatever you're afraid of, say it

three times fast, and it will never happen," and that's what I've done in my

fiction. Basically, I've said out loud the things that really terrify me and

I've turned them into fictions, and they've made a very nice living for me,

and it seems to have worked.'

Did you ever feel that, this time, the horror stories jinxed you; that

something you feared and had written about was coming true?

Mr. KING: No, it never even crossed my mind. It's strange because off and on

in my career as a writer, I have certainly written about car crashes and about

characters who've been hurt or injured in car crashes. There's a little boy

who's killed by a truck in "Pet Sematary." And in a book that's done in

manuscript, but hasn't been polished yet and readied for publication called

"From a Buick Eight," one of the main characters' father is killed in an

accident very similar to the one that almost killed me.

But I only used those things in my stories because cars and traffic accidents

are a part of our lives. They're something that, unfortunately, most of us

relate to, probably at a rate of three or four times as much--that is to say

three or four times as many people either have been in a car accident

themselves or know somebody who has, as have been injured with gunshots. So

it's a part of the American experience, and as such, of course, I've written

about it. But I never felt that I jinxed myself, no.

GROSS: When you were on FRESH AIR a few years ago, and we were talking about

the things that scared you most as a kid, you mentioned something that you

also describe in your new book, "On Writing." You talked about how, when you

were a kid, you had strep throat, and after that you had a terrible ear

infection, and in treating it, the doctor had to, with a needle, puncture your

eardrum on three separate occasions to let the infection drain, and it was the

worst agony you'd ever experienced. And, of course, the doctor, before doing

the procedure, kept saying that it wasn't going to hurt. You've had to go

through excruciating pain as an adult now, as a result of the accident and the

procedures and therapies that you've had to do as well. How has dealing with

the pain of the accident, the surgeries, the procedures, dealing with that

pain as an adult compare to dealing with it as a child?

Mr. KING: Well, as an adult, I always felt a lot more as though I were a

participant in what was happening to me. For instance, the therapy--and

anybody who's been in a bone-crunching accident knows that it's a very, very

difficult procedure to go through. When I woke up, I was in something that's

called an external fixator, which is a halo that goes over the leg and it

immobilizes the bone. It also immobilizes the joint, so that from June 19th,

I think, until probably, oh, toward the end of July I never bent my knee. And

in the old days, the '20s and '30s when people recovered from this sort of

accident, their leg was more or less frozen in place, so it became an organic

crutch. And nowadays, at least, we have therapeutic techniques to restore

mobility to the leg, but it's very, very painful.

And I can remember, yeah, in the "On Writing" book, I talk about having my

ears lanced to drain moisture and puss that was behind the eardrum. But as a

child, when you're faced with a procedure like that, you're in a uniquely

powerless situation because you don't understand what's going on, and you're

powerless to stop it in any case. You were mentioning I had to go back three

times, and the first time when I was told, `Don't worry, this won't hurt,' I

believed it. The second time I almost believed it. And the third time I knew

that it wasn't true, but I was still powerless to stop it and, to me, that's

the ingredient of a nightmare, even down to the fact that the doctor never

called me Stephen. He called me Robert. He would say, `Now, Robert, lie

down. This won't hurt.' And in my panicky child's way, I'm thinking, `Of

course it will hurt! Of course it will hurt! You're even lying about what my

name is!'

But when you get to be an adult, although it still hurts, the pain is still

there, I felt as though I were something of a participant in my own therapy,

so that the first step was to get the knee to flex enough so that the leg

would come down and the heel would touch the floor, and the pain of just that

was excruciating, and I just filled the house with my howls. I can't imagine

how my poor wife ever stood it, but the physical therapist, Ann(ph), just

would laugh and say, `You can do a little bit more, Stephen,' and I'd think,

`No, I can't. I can't do any more, Ann. Stop it. Let me stop.' And she

wouldn't. And then come the weights on the leg and all the rest of it, but at

least you know what's going on and you understand what the stakes are. And

when it came to having my ear lanced, children just don't understand.

GROSS: You know, in "Misery," the main character's a writer who's seriously

injured, and the woman taking care of him, his number-one fan, is really

torturing him and not giving him therapy. Did the nurses and therapists who

you worked with make zillions of "Misery" jokes?

Mr. KING: You know, they'd all read "Misery," and they worked for an outfit

called the Bangor Area Visiting Nurses. These are nurses who go into the home

and give home care. And I think one of them told me toward the end of the

period, where I needed full-time nursing, that they had all read it, and they

had all been called into the office by their superior and told in no uncertain

terms, `You don't make any "Misery" jokes.'

GROSS: And did they restrain themselves?

Mr. KING: They did. They were great.

GROSS: Stephen King. He'll be back in the second half of the show. His new

book is called "On Writing."

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Credits)

GROSS: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

Coming up, painkillers and hallucinations. We continue our conversation with

Stephen King about recovering from the car accident that nearly killed him.

And Lloyd Schwartz reviews a new collection of music composed by Samuel

Barber.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Back with more of our interview with Stephen King. He's still recovering from

the car accident that nearly killed him last year. He started writing again

just a few weeks after the accident. His new book "On Writing" is part

reflection on his craft, part memoir.

You write in the book that at some point you had to admit to yourself that you

had serious problems with alcohol and with cocaine. And because your wife

organized an intervention, you finally did something about it and got over

those addictions. After the accident, you had to take some pretty heavy

painkillers.

Mr. KING: Right.

GROSS: And those are pretty addictive. What's it like having to go back on

drugs, addictive drugs, knowing that you'd had a problem with them and that

you have what you describe as an addictive personality?

Mr. KING: Oh, one of the ways that--the way that it was described best to

me--you know that people who are alcoholics and drug addicts generally get

involved with support groups that have names that suggest that you shouldn't

talk about them at the level of press, TV, radio and films, and so I don't.

But I do know a lot of people as a result of attending those meetings who have

the problem that I do. And I heard one guy who'd been through this himself

describe it as being in one of those log-rolling competitions, where you get

up on a log and you see how long you can stay up before you get dumped back

into the river.

If I thought anything was unfair about what had happened to me, it was that

after struggling and winning a battle to get off all sorts and drugs and

alcohol--and I just didn't have a problem with beer and cocaine; I was an

addictive personality, period. I was smoking two packs of cigarettes a day.

I loved Listerine. I loved NyQuil. You name it. Boy, if it would change

your consciousness, I was all for that. And I was able to jettison almost all

of those substances out of my life.

And suddenly, you wake up in a hospital bed and you've got a phenyltol patch

on your arm and you're jacked up on morphine and you've got all these

different medications. And I was as grossed out by that, I think, as I was by

the injuries, thinking, `My God, I'm a junkie again.' And the way that I deal

with it, rightly or wrongly, is to try and make sure that you never exceed the

dosage that you're supposed to have for things like Percocet or Vicodin or any

of those things. And as long as you stay below the prescribed levels and as

long as you're making a reasonable effort to get clean, that's a good thing to

do.

On the other hand, as other people say in those programs that I attend, I

didn't get sober to suffer. And if I'm in a situation where I'm miserable and

medication will help that suffering, I'm going to take it.

GROSS: Do you still have to take painkillers?

Mr. KING: I'm almost off, but I still do take some, yeah, toward the end of

the day. Mostly, though, I'm clean.

GROSS: Is it hard to keep your...

Mr. KING: There's no such `mostly' for an alcoholic and drug addict anyway.

GROSS: Yeah, right. Right. Right.

Is it hard to keep your mind clear? You know, that's what people always

complain about with painkillers--it helps the pain, but it's hard to think

clearly.

Mr. KING: I think it depends on what you take. I've never detected any

emotional or mental change at all with the stuff that I take. Most of it is

time-released, and that might be why. But there certainly doesn't seem to be

any buzz.

GROSS: Now think early on when you're on the real heavy-duty painkillers that

there'd be some...

Mr. KING: You know, if I can just interrupt.

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. KING: With heavy-duty painkillers, there's a buzz, but you don't enjoy

it because you're totally screwed up.

GROSS: Right. Right. Right. But I think there were hallucinations that

came along with some of that early on.

Mr. KING: Uh-huh. There were a lot of hallucinations, very unpleasant.

GROSS: Yeah. I'm thinking your mind is wild enough without the

hallucinations. I mean, like, you have all these visions for these great

stories that you write all the time, and they're kind of, you know, crazy and

scary enough. So what's it like when your mind hallucinates?

Mr. KING: Well, at the time that I had the accident, I was working on the

book that we're talking about, "On Writing." But the book before that that

I'd published was called "The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon," and it was about a

little girl who gets lost in the woods and she survives from day to day.

She's got a little Walkman radio with her, and she listens to the Red Sox

baseball games and her hero is Tom Gordon, a real person who is the closer

for the Boston Red Sox.

And after the accident, when I was going through surgeries and I was being

loaded up with morphine, loaded up with VERSED, whatever it is that they give

you when they operate on you and then they bring you out on this stuff for

pain, I became convinced that Tom Gordon had killed his entire family, a la

O.J. Simpson, and that I was hiding in some sort of a hospital from him

because he might come and get me. And this was all totally in my mind. Tom

Gordon is a wonderful guy. He's a wonderful family man. And I just--who

knows where it came from, but it was just total hallucination.

And I had decided that there was this fellow who might be my friend in this

hospital who was in charge of physical therapy. He was like a phys ed.

instructor with a lot of muscles and a white shirt and the white duck pants

and everything. And this guy turned out to be the orthopedic surgeon who'd

actually put me back together again. He must have come into the operating

room at some point where I'd regained a little edge of consciousness. But

because of the drugs that I was on, I was convinced he was a character. In

fact, I seemed to be a character in one of my own books, and that was a very

frightening place to be.

GROSS: Yeah, I would imagine. Do you think that you got any ideas from these

hallucinations that you would use in a book?

Mr. KING: From the entire experience and having the broken leg and

recovering from the broken leg, those things I've used already in a book

called "Dreamcatcher," where there's a character who is a history professor

who's struck in Cambridge and has a broken leg and a broken hip and the things

that he goes through in the hospital. I would say that there's a surrealistic

touch to some of that that approaches those hallucinations. But certainly, I

have not used any of that stuff at this point. And I might someday. I really

might.

But those memories have faded a little bit for me. There's this saying that

if women really remembered labor pains, every child would be an only child.

And I think that whatever sort of serious pain that you had, your mind casts a

veil over that, so it's difficult to remember it in any detail.

But I also think, as a writer, that a lot of that stuff--in "On Writing," I

talk about muses that I call `the Boys in the Basement(ph)' because usually

when we think about muses, we think about these airy, fairy little female

sprites that kind of float around your head flinging this inspired happy dust;

whereas, I think of them as these blue-collar guys who live in the basement

and they sit around drinking beer and, you know, telling dirty jokes. And

every now and then, you go down and say, `Do you have any ideas for me?' And

the guy looks at you and says (speaking in different voice), `Yeah, I got an

idea. Yeah, here it is. Now go get to work and don't bother me anymore. I

got to polish my bowling trophies.'

So that's the kind of muse that I see. But I do think of them as people who

live in the basement. And in my mind, I equate that with the subconscious

mind. And I think that down there, on whatever that level is, I probably

still have a pretty good grasp of a lot of the things that I went through when

I was, you know, in terms of consciousness, only partly there, so that maybe I

could draw on that if I really needed to.

GROSS: My guest is Stephen King. His new book is called "On Writing." We'll

talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Stephen King is my guest. His new book is called "On Writing: A

Memoir of the Craft."

About a year before your accident, you had said that most writers have a

finite number of stories to tell and that you suspected you were reaching

your limit. And I'm wondering if the accident changed your feelings about

that or changed the kind of story that you wanted to tell, lead you in any

surprising and new directions.

Mr. KING: I think any major accident is a life changer. But you're asking

me was it an art or a craft changer, and I don't really think so. Obviously,

it has given me some new things to write about and some new experiences to put

in stories, and I've already begun that procedure. Given a choice, if

somebody had walked up to me and said, `Well, Steve, you can continue to live

the same old, boring, healthy life and you won't have any real, new

experiences and you can retire at 55, or you can go for the car accident. You

can get hit by the van and put in the hospital, and you'll get some new

experiences and you can write until you're 60. Which do you choose?' And

immediately I would say, `Give me the boring life. I'll stop at 55.' So I do

have some new experiences, and I probably will write some other things and go

on for awhile.

But, you know, there's a piece in The New York Times about Thomas Wolfe. A

small press is reissuing "Look Homeward, Angel" in its entirety, which is a

daunting idea because it's very big even in the edition that was published by

Scribners back in the '20s and '30s. But this version is 60,000 words longer.

I mean, 60,000 words is the length of "Carrie," so this is a fairly long

edition. And a lot of what Thomas Wolfe wrote was autobiographical. And he

said something that struck me that's always stayed with me. Somebody asked

him, `What is your purpose as a writer?' And Wolfe said, `My purpose is to

loot my life to the very walls--to loot my life to the very walls.'

And I think that every writer, particularly as they get a little bit

older--you have more of a tendency to look back. I mean, first novels have a

tendency to be almost unabashedly autobiographical. Later on, I think that

writers look at their lives with a little more consideration, and as you get

older, with a little more regret because you're aware of how much time has

gone by, you have a tendency to use those experiences and use those insights

until you get to a point where you say, `I've started to recycle things that I

said in the '80s,' or in some cases in the late '70s.' And when you get to

that point, I think that you say, `Really, it's time to leave this table, to

push back and to let it go.' And I think that for me what that means is there

would come a time where I would simply cease publishing stuff, but I might go

on writing because it's just fun.

GROSS: Yeah. As you point out in your new book, "On Writing," one of the

plots that has interested you in several of your books is `If there is a God,

why do such terrible things happen?'

Mr. KING: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: And that's one of the themes in "The Stand," "Desperation," "The Green

Mile." Is that the kind of thing you were wondering about yourself after the

accident? And I'm wondering if you believe in God--if you did before the

accident; if you did after the accident?

Mr. KING: Oh, I've always believed in God. I also think that's the sort of

thing that either comes as part of the equipment, the capacity to believe, or

at some point in your life, when you're in a position where you actually need

help from a power greater than yourself, you simply make an agreement. `I

will believe in God because it will make my life easier and richer to believe

than not to believe.' So I choose to believe.

Then, of course, you're left with these questions. `Why did this happen to

me?' you know? There's a story that I've told a couple of times about Job,

you know, the sorrows of Job. Job loses his wife. He loses his children.

He's covered with diseases. His land is taken away from him, all these

sorrows. And finally Job goes down to the coast of the ocean and faces the

waves and says, `God, all these terrible things have happened to me. All

these things, and I still love you. But I want to know why. Why did these

things have to happen to me? Why did they have to happen to Job, your good

and faithful servant?' And this cyclone comes down, and it comes across the

waves and it stops in front of him. And it says, `Job, I guess you just piss

me off.' And that's one way of looking at how God treats us.

I can also say, `God, why did this have to happen to me when if I get another

step back, you know, the guy misses me entirely?' Then God says to me, in the

voice that I hear in my head--which probably comes from the Boys in the

Basement as much as from God, the muses that I have, the ones that, you know,

basically tell me to `get lost, I'm polishing my bowling trophies'...

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. KING: ...these guys say, `On the other hand, Steve, if you'd taken

another step forward, you would have been killed. You didn't have any

permanent nerve damage. You've got a numb place on your leg, but your foot

works and your leg works.' So there are all these things.

And then these voices can go on and say, `Steve, why don't you get serious?

Six million Jews were killed in the '30s and '40s as a part of Hitler's little

ethnic cleansing program, and a million more Bosnian Serbs were killed in

their program of ethnic cleansing in the mid-'90s. So what are you

complaining about? You got a little busted hip. Why don't you just, you

know, pick yourself up and dust yourself off and get over it and don't be

worrying about things you can't understand?'

So again, I think that you make an agreement, and you say to yourself, `OK.

There's a God. Why? Because I choose to believe there's a God. Believing

makes my life better than not believing. Why did this happen to me? It

happened to me for some good purpose. What is that good purpose? I don't

know, but I choose to believe it's good because to believe it's bad would bum

out my whole day.'

GROSS: I had read that you were going to buy the van that struck you and

smash it. Did that actually happen?

Mr. KING: It never did happen. The van has been cubed. When I was in the

hospital, mostly unconscious, my wife got a lawyer who's just a friend of the

family. My son and his son went to school together, so we know him really

well. And she got in touch with him and said, `Buy it so that somebody else

doesn't buy it and decide to break it up and sell it on eBay, on the

Internet.' And so he did. And for about six months, I did have these, sort

of, fantasies...

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. KING: ...of smashing the van up. But my wife--I don't always listen to

her the first time. But sooner or later, she usually gets through. And what

she says makes more sense than what I had planned. And her thought was that

the best thing to do would be to very quietly remove it from this plane of

existence, which is what we did.

GROSS: Oh--and you can't say how.

Mr. KING: Sure I can. It went through a car crusher. It's a little cub

somewhere.

GROSS: Oh! Oh--so rather than you attacking it yourself--I got it. Oh,

that's...

Mr. KING: Yeah.

GROSS: And did you keep the cube?

Mr. KING: No, I didn't. I don't really know what happened to the cube. But

my idea about the van had always been to sort of smash it up the way that--in

the carnies of my youth, sometimes somebody would put a car up on in the back

of a flatbed truck and charge a quarter for three smacks with a sledgehammer.

GROSS: Uh-huh.

Mr. KING: And I thought we could do that for charity. And it still, at

times, seems to me like a good idea. But I have sort of a carnival mind, and

my wife is a little bit more sober.

GROSS: So great to talk with you again. Thank you so much.

Mr. KING: It's so great to talk to you. Just to hear your voice in my

headphones is nice.

GROSS: Thank you and continued good luck with your recovery. It sounds like

you've really been doing terrifically so far. So I thank you so much for

talking with us.

Mr. KING: Thank you for talking with me.

GROSS: Stephen King's new book is called "On Writing." Here he is singing

"Stand By Me," the song used in his film adaptation of the same name. Warren

Zevon is at the piano.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. KING: This is where it all begins.

(Singing) When the night has come and the land is dark and the moon is the

only light we'll see, I won't cry. I won't cry. No, I won't shed a tear just

as long as you stand by me.

And, darling, darling, stand...

Group of Singers: Stand by me.

Mr. KING: (Singing) ...by me.

Group of Singers: Stand by me.

Mr. KING: (Singing) Stand by me.

Group of Singers: Stand by me. Stand by me.

Mr. KING: (Singing) Just as long as you stand by me.

Group of Singers: Stand by me.

Mr. KING: (Singing) Now listen...

Group of Singers: Stand by me.

Mr. KING: (Singing) ...if the sky we look upon should crumble and fall and

the mountains should tumble into the sea, I won't cry. I won't cry.

Group of Singers: I won't cry.

Mr. KING: (Singing) No, I won't shed a tear...

Group of Singers: No, I won't.

Mr. KING: (Singing) ...just as long as you stand by me.

And, darling, darling, stand...

Group of Singers: Stand by me.

Mr. KING: (Singing) ...by me.

Group of Singers: Stand by me.

GROSS: Coming up, Lloyd Schwartz reviews a new collection of compositions by

Samuel Barber. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: New reissue of "The Music of Samuel Barber"

TERRY GROSS, host:

The American composer Samuel Barber died in 1981. And except for a handful of

pieces, most of his music doesn't get performed much. But classical music

critic Lloyd Schwartz says that there's been a revival of interest in Barber's

music. Here's Lloyd's review of a new reissue called "The Music of Samuel

Barber."

(Soundbite of music)

Unidentified Man: (Singing) One heart...

Unidentified Woman: (Singing) Two hearts. Two hearts.

LLOYD SCHWARTZ reporting:

As the nephew of the famous Metropolitan Opera contralto Louise Homer and the

life partner of the opera composer Gian-Carlo Menotti, it was inevitable that

the American composer Samuel Barber would turn to opera. His first opera, the

romantic melodrama "Vanessa," had its world premiere in 1958 at the

Metropolitan Opera and won the Pulitzer Prize. The plot is a little corny,

but the music still holds up. The Met later commissioned from him a grand

opera, "Antony and Cleopatra," for the opening of its new house at Lincoln

Center in 1966, but it was a bomb of atomic proportions, and Barber's

reputation never quite emerged from under that mushroom cloud.

In the last few years, though, there's been a neo-romantic revival.

Audiences, tired of atonality, want to hear tunes they can remember, and

Barber had a genuine gift for melody. His violin concerto and his setting of

James Agee's "Knoxville: Summer of 1915" for soprano and orchestra have

remained standard repertory items. And his moving "Adagio for Strings," which

was originally the slow movement of his string quartet, is so famous people

know it without even knowing who wrote it.

My favorite of Barber's three operas is a little gem, a 10-minute,

four-character opera called "A Hand of Bridge" that he composed in 1959, the

year after "Vanessa." And like "Vanessa," it has a libretto by Gian-Carlo

Menotti. In it, we hear the inner thoughts of two married couples as they are

playing their nightly bridge game. Geraldine(ph) is desperate about the

impending death of her mother, the only person who has ever loved her. Her

husband, David, frustrated by his subservient, white-collar job, has

sadomasochistic fantasies about 20 naked girls and 20 naked boys and

(technical difficulties) scented wine from cups of stubenglass(ph). Their

friend, Sally, escapes from the boredom of her marriage by shopping and is

currently obsessed with a hat of peacock feathers, while her husband, Bill,

daydreams about his affair with a woman named Symboline(ph) in one of Barber's

most seductive lyric tunes.

(Soundbite from "A Hand of Bridge")

SALLY: (Singing) I want to buy that hat of peacock feathers. I want to buy

that hat of peacock feathers. I want to buy that hat of peacock feathers I

saw this morning at Madam Charlotte's(ph). Look across, there is a red one

with a tortoise shell ...(unintelligible). And look, there is a beige with a

fuchsia rim. Still, I think I'll buy that hat of peacock feathers from the

(unintelligible).

BILL: (Singing) I'm sorry, dear. I wonder what she meant by `always being'

(technical difficulties). Has she found out about Symboline? Symboline,

Symboline, where are you tonight?

SALLY: (Singing) I want to buy that hat of peacock feathers.

BILL: (Singing) Where are you tonight? On whose mouth are your

(unintelligible) senses might ...(unintelligible) with your genuine certain

breath? On whose black shoulder will you strew your blond hair? To whose

fleeting violence will your breasts surrender? Is it Christopher calling...

SALLY: (Singing) I want to buy that hat of peacock feathers.

BILL: (Singing) ...or Martin or Manfred(ph), Chuck, Tommy or Dominic(ph)?

Symboline, Symboline, oh, if only you were my...

SALLY: (Singing) I want to buy that hat of peacock feathers.

BILL: (Singing) ...wife playing cards with me every night. If it only were

you, I might take off with me at the end of the day and strangle in the park.

SALLY: (Singing) I want to buy that hat of peacock feathers. I want to buy

that hat of peacock feathers.

The queen--you have trumped the queen.

SCHWARTZ: This isn't psychological profundity, but it's a vivid picture of

1950s middle-class anxieties and the verbal, melodic and rhythmic

juxtapositions. The skillful interweaving of the characters' internal

thoughts with the card game they're playing are delicious.

This album, "Music of Samuel Barber," also includes several early choral and

orchestral pieces, as well as the famous "Adagio for Strings" in a performance

led by the well-known cellist conductor Antonio Janigro. In all their hands,

some of the best music of the 1950s is still alive and well.

GROSS: Lloyd Schwartz is classical music editor of the Boston Phoenix and the

author of a new book of poems called "Cairo Traffic."

(Credits given)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

(Soundbite of music)

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.