Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on December 29, 2020

Transcript

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

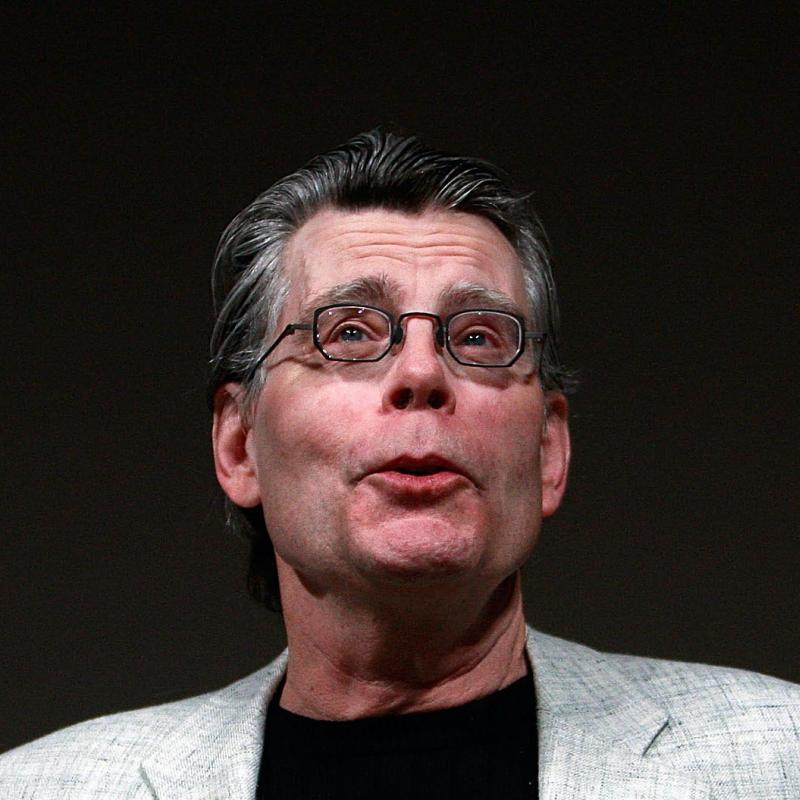

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Life during the pandemic has been feeling like something Stephen King dreamed up. About 40 years ago, in his novel "The Stand," he wrote about a virus that's 99% lethal and wipes out most of the population. That virus was accidentally released by a lab developing biological weapons. "The Stand" was adapted into an ABC miniseries back in 1994. A new miniseries adapted from "The Stand" is now streaming on CBS All Access.

We're going to listen back to the interview I recorded with King early in the pandemic, in April, the month that he published "If It Bleeds," a collection of novellas. The main character of the title story is a private eye, Holly Gibney, who was also a character in several other King books, including "The Outsider," which was adapted into an HBO series starring Cynthia Erivo as Holly. Like in "The Outsider," in "If It Bleeds," Holly is confronted by a force of evil.

Here's my interview with Stephen King from April.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

GROSS: Stephen King, welcome back to FRESH AIR. I am so glad that you are well. Is this pandemic the closest thing you've come to living in one of your own horror stories?

STEPHEN KING: (Laughter) Well, it is and it isn't. I had a lot of people get in touch with me after Donald Trump got elected and said...

GROSS: (Laughter).

KING: ...This is just like "The Dead Zone." There's a character in "The Dead Zone" named Greg Stillson, who is kind of an avatar of the common man. And he becomes a state representative, and then he rises to the presidency. So this is the second time. And now that Trump is actually president of the United States and there is a pandemic worldwide - I guess that's what pandemic means - that it seems almost like those two books have cross-pollinated somehow. It's not very comfortable to be me. I keep having people say, gee, it's like we're living in a Stephen King story. And my only response to that is, I'm sorry.

GROSS: You know, you write horror stories, and a virus is kind of perfect. You know, viruses are shape-shifters. They keep - like, the flu virus keeps changing every year or two. That's why we always need new vaccines. And viruses aren't exactly alive because they can't - they need some kind of living cell to inhabit in order to survive. So I think scientists say that viruses aren't really alive, or they're somewhere between alive and dead. That sounds kind of like a horror story.

And the fact that they live in us and, like, we are their hosts and then they make us sick and, in some cases, can kill us, that really - like, that's the kind of thing you could have invented from scratch. But viruses are real. Do you think of viruses as being just, like, the essence of a horror story in how they work in us?

KING: Yes, I do. You know, for years, I was...

GROSS: Oh, can I add one more thing?

KING: Yes.

GROSS: You can't see them. Like, you write sometimes about the kind of evil that - like, it can manifest itself in a presence. It can manifest itself in a person. But it exists as an entity. It exists just as pure evil, too. And with a virus, like, the entity, you can't see it unless it's in a body. I mean, you could put it under a microscope, but without a microscope, you can't see it. You don't know it's there, but it is. That's like a horror story, too.

KING: It is. And when you were talking about viruses not being alive or dead, this really is like one of those zombie movies. It's the - you know, the night - we're living in the "Night Of The Living Dead" in a sense because the virus is just what it is, which is something that's almost incomprehensible to us. And it's incomprehensible to science, too, which is one of the reasons why I think people have to watch out for quack cures.

The thing is, because it's invisible, because we can't see it, we hear these things on the news where they're saying, look - if you have to go out, make sure that you don't touch your face. When you come back in, make sure you wash your hands. Be careful about taking off your shoes, and when you take your shoes off, put them in a certain place, and then wash your hands because you can get the virus on your shoes. So that after a while, I think that a lot of people in America are living almost like Howard Hughes, who had this...

GROSS: Yes. Yes.

KING: ...Pathological cleanliness thing. We're all washing our hands. And it's easy to imagine - Terry, think of this. They could be on your hands right now - germs, viruses, like wagon wheels just they're in your hands, waiting to get inside the warmth of your body, where they can multiply and spread. And once you start thinking about that, it's very hard to unthink it. So it's easy to start to be paranoid about it. But on the other hand, what's the alternative?

GROSS: I'm glad you mentioned Howard Hughes because I keep thinking about the scene in Martin Scorsese's film "The Aviator," where Leonardo DiCaprio as Howard Hughes...

KING: He's in the bathroom, isn't he?

GROSS: He's in the bathroom, exactly. And he's trying to get out of the bathroom, but because he's so compulsive about washing his hands and cleaning his hands, every time he washes his hands he has - he can't reach the door with a paper towel.

KING: He can't - yes.

GROSS: And so he can't get out because every time he touches something, he has to go back and wash his hands again, and the scene keeps going on. And that's the world I feel like I'm living in right now. I'm not sure I have any skin left on my hands (laughter) from washing so much.

KING: Yeah. Oh, that's the...

GROSS: Do you like that scene? I know you...

KING: Yeah.

GROSS: Yeah.

KING: I was thinking about that scene, just as you were and as I'm - I'm sure a lot of people who've seen that movie can relate to that immediately, you know, to the idea of - these things are all over our hands. We're making complexes in our children that are going to last a generation. You know, for me, as a guy who is in his 70s now, I can remember my mother talking about the Great Depression. It made a scar. It left trauma behind.

And I think that for our children, when they grow up - or let's put it this way - my grandchildren, when they grow up, my granddaughter who can't see her friends, can only Skype them once in a while. She's stuck in the house. She can go out in the yard. When her children say, oh, my God, I'm so bored, I can't go out, that little girl who becomes a woman is going to say, well, you should have been around in 2020 because we were stuck in the house for months at a time. We couldn't go out. We were scared of germs. You see what I'm saying?

GROSS: I think you're absolutely right. I completely - I feel exactly the same way.

The character in the title story of your new collection, Holly Gibney, is also in "The Outsider" and several other of your novels. So Holly Gibney, she runs a detective agency. Do you consider her to have a obsessive compulsive disorder or to be on the autism spectrum or to have just, like, a little bit of psychic ability? How would you describe what her...

KING: (Laughter).

GROSS: ...Makeup is that gives her a kind of special power, a special insight?

KING: Well, first of all, can I say that I just love Holly, and I wish she were a real person and that she were my friend because I'm so crazy about her. She just walked on in the first book that she was in, "Mr. Mercedes," and she more or less stole the book (laughter). And she stole my heart.

(LAUGHTER)

KING: But the short answer to your question is, I see the Holly of the books as an obsessive compulsive with a huge inferiority complex. The character, the Holly that Richard created, was more of a, I would say, on the autism spectrum, kind of a - what do you call a person who is just very capable in one area, you know, somebody who can do numbers in their head, boom? Holly - that Holly, Richard Price's Holly of the HBO series is that kind of person, where she can remember who did every rock song for 35 years, but she's never listened to a record.

GROSS: Do you believe that some people have special powers of perception?

KING: Oh, yeah. I've seen it. I know that - I used to be good friends with Stephen Jay Gould. We shared seats at Fenway Park. And he would bring his son along. And his son was on the spectrum. But he would say to you, tell me what your birthday was and how old you are. And if you did that, he would immediately tell you the day you were born on. He just had that particular talent in his head. There are kids who can suddenly sit down and play the piano. They just hear the music in their heads and - or there are kids who are 7 or 8 years old who are chess prodigies. That's the word I was looking for - prodigies.

And so, yeah, there are people who have those special powers. And one of the things that fascinates me about this whole spectrum that I write in, which is a pretty wide - people can call me a horror writer if they want to. And that's fine. As long as the checks don't bounce, I'm happy with that. But I think that I do a lot more. And I'm interested in the mystery of what we are and what we're capable of doing.

GROSS: You know, in the opening to the Holly Gibney story in "If It Bleeds," your new book, you mentioned that the detective who worked with Holly in the book "The Outsider," that his perception of reality was totally changed by that incident because he's dealing with something beyond our perception. He's dealing with something that doesn't seem rational or scientific, which is just this entity of evil.

Do you feel like you live in a different reality than other people? (Laughter) You know what I mean? Because you're always writing about things that are outside of our perception and that are outside of what we consider to be, you know, the real, visible, perceivable world.

KING: Yeah. I hear your question. And I think the answer is that, 20 hours a day, I live in the same reality that everybody else lives in.

GROSS: (Laughter).

KING: But for four hours a day, things change. And if you ever ask me how that happens or why it happens, I'd have to tell you, it's as much a mystery to me as it is to anybody else. All I know is that when I sit down in front of the - well, it's a word processor now. It used to be a typewriter. Well, it's actually a computer now. Things change.

And in all the years that I've been doing this since I discovered the talent when I was 7 or 8 years old, I still feel much the same as I did in the early days, which is - I'm going to leave the ordinary world for my own world. And it's a wonderful, exhilarating experience. I'm very grateful to be able to have it.

GROSS: Why did you leave your - you know, the actual, you know, world for your world, but make your world such a frightening world?

KING: Well, I am interested in frightening people, actually. I'm like the little boy in the Charles Dickens story - I just want to make your flesh creep. And that's OK. But what I'm really interested in as a writer that I come back to time and time again is the intrusion of the unexpected and the strange into our everyday life. And I think that that's a kind of - an honorable theme because we all face unexpected things. We're going through one now as a society. So I like to explore that world where something strange happens to ordinary people.

GROSS: We're listening to the interview I recorded last April with Stephen King. We'll hear more of it after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to the interview I recorded last April with Stephen King, after the publication of his collection of novellas called "If It Bleeds." The main character in the title story, Holly Gibney, is also a main character in the HBO adaptation of Stephen King's novel "The Outsider," in which she was portrayed by Cynthia Erivo. In "The Outsider," Holly is investigating a case that she believes involves a supernatural entity that is the personification of evil.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

GROSS: In "The Outsider" - and this is also mentioned in "If It Bleeds" - you refer to the story of El Coco, which is a kind of mythical story that has its origins in various, you know, Spanish, Hispanic cultures. Why don't you describe El Coco and why you're interested in that story.

KING: I found El Coco after I had started to work on "If It Bleeds." I knew that there was an outsider because that's what the book was about. I'm interested in exploring the idea of outside evil. I find it comforting to think that there can be evil that doesn't necessarily come from the hearts and minds of men. And once I had set up this situation where there was a creature that could take the face and the form of someone else - who could become that person's doppelganger, I looked around for myths that would play into that. And the one that I found in a children's book, actually, was El Coco.

GROSS: So describe El Coco.

KING: Well, El Coco is a creature that lives on the fear and the pain of other people. In the myths, he takes bad children. He's a very thin man in a black coat with a white face. And what you tell the children - because we save our scariest stories for the children - is that if you're a bad kid, you will probably see El Coco crawling on your ceiling. I just love that image because it's spiderlike - the tall, thin man in the black coat. And he carries a bag with him. And if you're a bad child, he will pop you into his bag and take you away to his lair, which is supposedly a cave. And at that point, he will kill you and rub that child's fat on his body and regenerate and be a young person again.

GROSS: Wow. That's a lot (laughter) - there's a lot in that story. But the idea of this El Coco feeding on fear and on grief - I mean, that's when you're at your most vulnerable.

KING: Yeah, it is. And one of the things that I found extremely powerful that I wanted to use was that El Coco only starts by getting someone - it's Terry Maitland in "The Outsider" - to take the rap, if you will, for his crime. But then that creature hangs around and feeds on the grief and the pain and the hurt of all the people that are left behind. The whole family, the whole Frankie Peterson family, ends up destroyed because of El Coco. And El Coco tries to do the same thing to Terry Maitland's family, starting with the kids, who are the most vulnerable.

So - but I liked that idea. I used the cave idea at the - for the conclusion of the book and the miniseries, too, where I was able to put El Coco actually in a cave. So I stuck to the legend as much as I could.

GROSS: You grew up in the Methodist church. You went to church as a child. Given your bent as a writer, were you especially interested in stories about Satan?

KING: No, I wouldn't say I was especially interested in stories about Satan. I was more interested in the idea that Satan causes us to do terrible, terrible things. And the story, I would say, that fired my imagination the most was the story of Job. And I loved the language in that, the Old Testament - the King James language, where the story starts by saying that God says to the devil, what have you been up to, Satan? And Satan says, oh, I've been going up and down upon the earth to see what misery I could cause.

And so then they make a bet about Job, who basically is this sort of schmoo (ph) who's not doing anything wrong, and God says, do everything to him you want to do - just don't harm a hair of his head - and we'll see what happens. So the guy's crops die. The guy's livestock dies, then all his kids die. And after all that - this is where it kind of lost me - it actually has a happy ending (laughter). Job remarries and has more kids.

GROSS: So tell me more about why you find that story so interesting.

KING: Well, I think mostly because the idea that the devil can meddle in human lives, which goes back to the whole idea of whether or not - this is a question that's fascinated me all my life. Is there such a thing as outside evil? Are there demons, devils, ghosts, possessions, horrible things that come to us from outside, or is it all built into our DNA?

The Bible likes to have it both ways. There's this story of Job, where the devil kind of - the devil and God, in concert, cause all these things to happen. And then there's the story of the tree of good and evil, where you sort of get it all blamed on Eve, who just - man, she couldn't stop looking at that apple and saying, that must really be good - or the stories of Moses and all the people who built the golden calf because that's human failings - that it's human weakness. So I like to - I think it's actually comforting to think that there's an outside evil that's not our fault.

GROSS: We're listening to the interview I recorded with Stephen King last April, after the publication of his collection of novellas, "If It Bleeds." We'll hear more of the interview - and we'll hear from Patrick Stewart - after we take a short break. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Let's get back to my interview with Stephen King. His novel about a pandemic, "The Stand," has been adapted into a new TV miniseries that's streaming on CBS All Access. We spoke early in the pandemic, in April, the month he published "If It Bleeds," a collection of novellas.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

GROSS: I want to read something that you recently tweeted - if you think that artists are useless, try to spend your quarantine without music, books, poems, movies and paintings. What led you to write that? Do you think people think of artists as useless?

KING: I didn't write it. I saw it on Twitter myself and reposted it. I didn't make a comment or anything. I just put it up. I never thought anybody would assume that I had written that. But it got an awful lot of retweets. And what struck me about it when I put it up was that we all need escape hatches, even in the most ordinary times, when we can go out and we can have social intercourse with people, we can meet on the street, we can gab, we can go to a movie - oh, my God, Terry, how I miss going to the movies...

GROSS: Me, too.

KING: ...You know, just sitting there with a - oh, yeah. I miss being with people. I miss going out to a restaurant and sitting, you know, and talking with somebody and having fun. Can't do that. I'm in the house. And I think that if I didn't have a good book to escape into - I'm reading this wonderful book now called "Dare Me" by Megan Abbott. Wonderful story. I've got Netflix. Thank God for Netflix. I'm watching this wonderful series called "Babylon Berlin."

So I can leave coronavirus. I can leave the self-quarantine and go back to Berlin in 1929. It's an escape hatch. It's a way to use your imagination as a force for good, where you can actually - by making believe, you can increase your serenity. You can take a little vacation from everything that's going on. That's the purpose of art. And it doesn't have to be a TV show, and it doesn't have to be a movie. It can be a poem. It can be going outside and looking at the spring that's just starting to come.

I think - every day, I like to take a few minutes to say, this is my life; I'm present in my life at this moment, and this is what I see, and this is what I feel. I think that you can't spend your whole day doing that. You'd go right out of your ever-loving mind. But once in a while, it's a good thing, and the imagination is a good thing. It's not always so good in the middle of the night, you know, when you wake up and you think, I think I heard something under my bed. That's maybe not such a good thing. But it's a double-edged sword. There's a good side. There's a bright side to the imagination, and there's a dark side to it. And I'm sure that we've all been there. And I hope that tonight, Terry, when you go to bed...

GROSS: (Laughter).

KING: ...That you'll keep your feet under the covers because it would be awful, and I wouldn't want you to think about this after the lights go out. It would be - please don't think about a hand creeping out from under your bed...

GROSS: (Laughter).

KING: ...A cold hand and then lightly gripping your ankle. I mean, you won't think about that, will you?

GROSS: No, I won't because that's not what's going to be scaring me in the middle of the night. And you know what is going to be scaring me in the middle of the night. But - which makes me wonder, like, how do you feel about your stories in a time like this? And what I mean is, your stories are about human nature and human vulnerabilities and the things beyond our perception, and they're also intended in part to scare people. You like scaring people. Part of your stories have to do with the world of horror. And we're surrounded by such - we're living in a horror story now. So what do you see as the role of, you know, horror fiction or horror movies in a period when the world itself is so frightening?

KING: Well, they're like dreams, aren't they? You're able to go into a world that you know is not real. But if the artist is good - the filmmaker or the novelist, maybe even the painter - for a little while, you're able to believe that world because the picture of it and the depiction of it is so real that you can go in there. And yet there's always a part of your mind that understands that it's not real, that it's make believe.

GROSS: Stephen King, thank you so much for talking with us. Thank you for your books. And I wish you and your family good health. And be well. Thank you.

KING: Thank you. And right back at you - be healthy and be safe.

GROSS: My interview with Stephen King was recorded in April, the month his collection of novellas "If It Bleeds" was published. After we take a short break, we'll hear from Patrick Stewart, who returned this year to his role as Captain Picard in his series "Star Trek: Picard." This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Fans of "Star Trek" and Patrick Stewart were delighted to see the actor return this year to his most famous role, Captain Jean-Luc Picard in the CBS All Access series "Star Trek: Picard." He made his first appearance as Picard in 1987 and has since starred in seven seasons of "The Next Generation" and several "Star Trek" films. Production for the second season of "Picard" is slated to begin in February of 2021.

It's hard to imagine now, but Patrick Stewart was kind of a longshot to play the lead in a sci-fi TV show. At the time, he was best known as a member of the Royal Shakespeare Company. He faced a lot of skepticism about whether he was right for the role, including from "Star Trek's" creator, Gene Roddenberry. But Stewart went on to embody one of "Star Trek's" most beloved characters. Patrick Stewart has continued to work on many other projects, including multiple Shakespeare productions, his one-man version of Charles Dickens' "A Christmas Carol" and several X-Men movies as Charles Xavier. During the pandemic, Stewart provided a little light on Instagram by reading all of Shakespeare's sonnets to his followers, finishing the last one in October.

We're going to hear the interview FRESH AIR producer Sam Briger recorded with Patrick Stewart in July.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

SAM BRIGER: Patrick Stewart, welcome to FRESH AIR.

PATRICK STEWART: Thank you, Sam. I'm very happy to be talking to you.

BRIGER: I'm happy to talk to you, too.

When you were preparing for the new show, did you go back and watch any of those old episodes from "The Next Generation?" And if so, what were your thoughts about your performance then?

STEWART: I - from the very beginning, once I had said, OK, I'm on board, there was not a day when I didn't think, OK, this evening, right, I'm going to sit down...

BRIGER: (Laughter).

STEWART: I'm going to watch "Encounter At Farpoint," which was our pilot episode of the series. And I never did. I ended up never watching a moment of "Next Generation" because - OK, I would have been reminded of some things that I'd forgotten. But that character was inside me. And the longer that we did "Next Generation," the more of Patrick Stewart got into Jean-Luc Picard. And so, finally, I felt that I don't need to do that research; what I need to do now is find out who he has become and really explore that and try to make that as authentic as possible, as something that happened to a man whom we remember very vividly from "The Next Generation" days.

BRIGER: Well, I guess it's too late for this to help as research, but I thought we could maybe listen to a moment from "The Next Generation," if you don't mind. This is a particularly good Picard monologue. This is from an episode called "Measure Of A Man." And this episode actually connects to your new series, "Star Trek: Picard."

The scene we're going to play, Picard is defending his friend and officer Data in this tribunal, which is trying to decide whether Data actually is - Data is an android, and they're trying to decide whether he should be considered a living being with rights or whether he's a piece of machinery owned by the Federation, who want to sort of take him apart, dismantle him and try to figure out how to make more of them, which I think would be used as workers without any rights. So let's just hear a moment of this.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION")

STEWART: (As Jean-Luc Picard) Your honor, a courtroom is a crucible. In it, we burn away irrelevancies until we are left with a pure product - the truth for all time. Now, sooner or later, this man or others like him will succeed in replicating Commander Data. Now, the decision you reach here today will determine how we will regard this creation of our genius. It will reveal the kind of a people we are, what he is destined to be, if we reach far beyond this courtroom and this one android. It could significantly redefine the boundaries of personal liberty and freedom - expanding them for some, savagely curtailing them for others. Are you prepared to condemn him and all who come after him to servitude and slavery? Your honor, Starfleet was founded to seek out new life. Well, there it sits, waiting. You wanted a chance to make law. Well, here it is. Make it a good one.

BRIGER: That's a scene from "Star Trek: The Next Generation." That was my guest Patrick Stewart, who has a new show, "Star Trek: Picard."

So, Patrick Stewart, listening back to that, you know, what's your reaction to your performance or to the character at that point? Do you have any thoughts?

STEWART: My. You have to believe how extraordinary that was for me (laughter) to listen to that speech, something which I learned and performed probably - I think it has to be 30 years ago. And I applaud how passionate I was and that I was not afraid of letting my feelings show because Picard was a man who, for the most part, kept his feelings very much under control. I'm not saying he was dishonest, but he felt that emotions can blur a situation or a conversation or a dialogue. But there was no sense of that - was there at all? - in any of that.

And I'm also very impressed with the terrific piece of writing. And I don't know who was responsible for that speech, but I've got a feeling that there is one word in what we've just heard that actually didn't belong to one of the writers. I use the word slavery at one point, and that word was given me by Whoopi Goldberg. I remember when she and I - it might have been the same episode, "The Measure Of A Man" - I think it could have been - when Whoopi and I had a scene in the bar of Ten Forward. And in a break, Whoopi said to me, you know, what we're actually talking about here is slavery, and I think it wouldn't be a mistake to introduce that. And so I think that was why that word cropped up. And I was so thrilled that Whoopi had proposed it and so proud that everyone approved it and it went into the episode.

BRIGER: This might be a stupid question, but I'm going to ask it. Jean-Luc Picard is French, so why doesn't he have a French accent? I mean, they're - in "Star Trek," you have Russian accents, you have Scottish accents, Irish accents. Why does Jean-Luc Picard have a British accent?

STEWART: Somewhere in the Paramount archives, there ought to be a videotape of me speaking Picard's lines with a French accent (laughter). They did actually want me to do that.

BRIGER: So was it rejected?

(LAUGHTER)

STEWART: Oh, yes. I mean, I don't know that my French accent - I mean, obviously, if they'd wanted it, I would have worked on it and made it as impeccable a French accent as I could. But I think I know what I did. You know, the famous introduction - space, the final frontier - I did that. You know - space, the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise. Well, that's how I did it.

(LAUGHTER)

STEWART: And it never came up again.

GROSS: We're listening to the interview FRESH AIR producer Sam Briger recorded with Patrick Stewart. We'll hear more of the interview after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to the interview FRESH AIR producer Sam Briger recorded in July with Patrick Stewart. This year, Stewart returned to his role as Jean-Luc Picard in the CBS All Access series "Star Trek: Picard." Stewart had played Picard in "Star Trek: The Next Generation" and several "Star Trek" films.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

BRIGER: I wanted to talk a little bit about your early years. You were born and raised in Yorkshire. And for the first five years of your life, you didn't know your father. He was serving in the war in a parachute regiment, and he was actually also one of the last men rescued at Dunkirk. We'll talk about this. It sounds like he suffered from what was not known then as PTSD, but certainly it sounds like he had that. But I was wondering, did it scare you when he returned from home? I mean, here was this person that you didn't know who is now living in your house.

STEWART: Yes, it did. I was very intimidated. My mother was a loving, charming, sweet, adorable person, and he was an interesting and exciting and colorful person. And, of course, he'd had this extraordinary career which had left him as a superstar in the noncommissioned officer sense. But, also, there were other aspects to it, which I only discovered the details of, to my profound regret, a few years ago.

I've talked to an authority on PTSD, told him about my father's behavior and his weekend alcoholism and his mood swings and the violence towards my mother - all of this I've talked about in the past. And he said, these are classic symptoms; there is no doubt your father was severely affected and needed medical help - which, of course, he never got. It made me sad - because I've given my father bad press over the years - that I couldn't speak to him now and ask him about these feelings and what it was and what he'd experienced.

BRIGER: When did you start feeling a connection to acting itself? I mean, it sounded like it was pretty young.

STEWART: It was about the time that Cec (ph) Dormand put the copy of "Merchant Of Venice" into my hand. He cast me in a play with adults. A lot of the staff of the school I went to, thanks to the enthusiasm of the headmaster, loved amateur acting. And most of the company - not all of them, but most of them - were teachers in my school. And we did a play called "The Happiest Days Of Your Life," which was about two schools merging. It's a brilliant comedy. It was made into a film. And there was a character called Hoppe Croft Miner (ph), who is a 12-year-old public school boy. And they cast me as that. There was also a young girl in it, too.

But first of all, I loved working with adults, especially the adults who were my teachers. And the most important thing that happened to me was that the first time I walked onto that stage to play my role, I felt safer - and I mean literally, physically, emotionally safer - than I had ever felt in my life. I think it must have been that that drew me back to acting. And then I joined other amateur groups. At that time, there was no consideration of becoming a professional. I just loved the experience of being someone else, not being Patrick Stewart and exploring what my life might be like if I were someone else.

BRIGER: So you said you were safer and you liked not having to be Patrick Stewart. So was acting an escape from your home, from your family life, then?

STEWART: Yep, all of that and, also, not having to feel that I was a failure. You know, I'd had friends who had taken the 11-plus and gone to grammar school, you know, when - friends I'd had when I was 8, 9, 10. I was cut off from them because I wasn't scholarly. I wasn't academic. But finding that people wanted to have me in their plays and productions and so forth - and we did quite a lot of acting in the school. Where I grew up, you were not thought weird if you were a performer, not remotely. On the other hand, it was actually applauded and loved. So to sing, to play an instrument, to act a scene, to recite a poem - these things were respected.

BRIGER: You've said that when you first started, when you first started acting, your performances were cautious and that you didn't want to expose yourself too much. What did you - what do you mean by that?

STEWART: Oh, yes. And I was told about it by my - the director of my acting school. I went to the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School. And towards the end of my two years there, he called me into his office and gave me a pretty tough talking to. But the last thing he said to me was, Patrick, you will never achieve success by insuring against failure. And I thought I knew what he meant, but I didn't - not for years and years and years. And I learned that you have to take risks. You have to be brave. You have to step into the unknown. You have to jump off the edge of the cliff. All of those things are required of actors. Once I'd finally understood that, I knew what direction I had to go in.

BRIGER: You know, when you were in "Star Trek: The Next Generation," there - obviously, the show plays with time. And there were a few opportunities where you played Jean-Luc Picard as an older man. I was just wondering what it's like to play him now as an older man yourself.

STEWART: (Laughter) Well, learning lines is a bigger challenge than it used to be. I used to learn lines so easily. Now when we're shooting the series, I have the week's work laid out in front of me. And over the weekend, I make sure that I am DLP - dead-letter perfect - of the first two days of work, Monday and Tuesday. And then I'm really familiar with Wednesday and quite familiar with Thursday and Friday so that each day, I will be on top of what I have to do insofar as just learning the lines goes. And I stick with that.

Other than that, one of the nice things about being 79 and playing a man who's a couple of years older is I don't have to act it. I just am 79. I'm 80 in a month's time. So, I mean, no one can accuse me of being a fake 80-year-old because (laughter) it's what I am. And my, you know - I forget that I've said things. And I forget people's names and telephone numbers and all of that. My wife is blessedly patient with me.

BRIGER: Well, one more question like that. I mean, you - in your past, you've had the opportunity to play older men. Like, you've played King Lear and Ebenezer Scrooge, Prospero. Looking back at those performances as - when you were a younger man but portraying an older man, what do you think you got right or didn't get right? Or what are you surprised about now, being a 79-year-old, that you wouldn't have been able to incorporate into your roles back then?

STEWART: Well, it's what - the one thing I've already talked about. I'm braver than I was when I was 35. I am not averse to risk-taking. And I don't judge myself. I used to do that so much. Ah, Patrick, that's not good enough. That's not good enough. You could've done that differently. You could've done it better. That gets in the way of spontaneity and real feeling coming into something. So I'm braver now than I was when I was much younger.

BRIGER: Patrick Stewart, thank you so much for your time. I really enjoyed speaking with you. I've been really enjoying seeing you on television. And I'm looking forward to Season 2. And it's just been a real delight to speak with you. So thank you so much.

STEWART: Oh, thank you. I've enjoyed it, Sam, very much, indeed.

GROSS: Patrick Stewart spoke with our producer Sam Briger in July. Stewart stars in the series "Star Trek: Picard," which is streaming on CBS All Access. Season 2 is scheduled to start production in February 2021.

Tomorrow on FRESH AIR, we'll remember Broadway star Rebecca Luker. She died last Wednesday of ALS, Lou Gehrig's disease. She was 59. She won Tony nominations for her performances in "Show Boat," "The Music Man" and "Mary Poppins" and starred in a revival of "The Sound Of Music." We were fortunate in having her on our show four times. We'll hear excerpts of those interviews. I hope you'll join us.

We'll close today by remembering Tony Rice, the most influential bluegrass guitarist of his generation. He died Christmas Day at the age of 69. Rice's first big break was in the early '70s as the singer and guitar player for J.D. Crowe's progressive bluegrass band The New South. He was also the guitarist in David Grisman's original quintet, which played a blend of bluegrass, folk and jazz. Due to health issues, Rice stopped singing in the early '90s and stopped playing guitar in 2013. But here he is doing both on this 1979 recording of the song "Old Train."

I'm Terry Gross.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "OLD TRAIN")

TONY RICE: (Singing) Old train, I can hear your whistle blow. And I won't be jumping on again. Old train, I've been everywhere you go, and I know what lies beyond each bend. Old train, each time you pass, you're older than the last. And it seems I'm too old for running. I hear your rusty wheels scrape against the rail. They cry with every mile, and I think I'll stay a while.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.