Other segments from the episode on August 28, 2017

Transcript

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

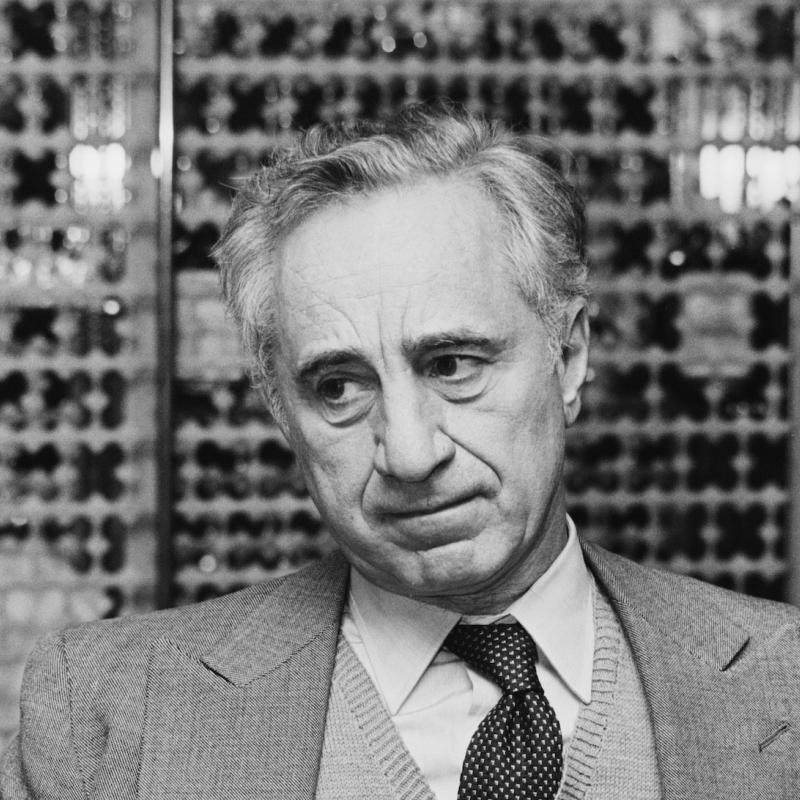

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. This year marks our 30th anniversary as a daily NPR program. And this week, we're featuring some of our favorite interviews from the early days. To start today's show, we have a 1988 interview with Elia Kazan. He directed Marlon Brando on "A Streetcar Named Desire" and "On The Waterfront," and directed "East of Eden," "Splendor In The Grass," "Baby Doll," "A Face In The Crowd," and "The Last Tycoon."

Kazan had an equally important career in the theater. In the 1930s, he worked with the Group Theatre, where he followed the vision of Lee Strasberg and learned the style of acting that became known as the method. He later co-founded the Actors Studio with Strasberg.

Many of Kazan's friends and colleagues never forgave him for naming names when he was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1952, in the era when people accused of being Communists lost their jobs. For many years, Kazan refused to publicly address the subject, but he broke the silence in his autobiography, "Elia Kazan: A Life." I spoke with him when it was published. We started with this classic scene from "A Streetcar Named Desire."

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE")

MARLON BRANDO: (As Stanley Kowalski, yelling) Hey, Stella.

PEG HILLIAS: (As Eunice Hubbell, yelling) You quit that howling down there, and go to bed.

BRANDO: (As Stanley Kowalski) Eunice, I want my girl down here.

HILLIAS: (As Eunice Hubbell) You shut up. You're going to get the law on you.

BRANDO: (As Stanley Kowalski, yelling) Hey, Stella.

HILLIAS: (As Eunice Hubbell) You can't beat on a woman and then call her back because she ain't going to come. You're going to have a baby.

BRANDO: (As Stanley Kowalski) Listen, Eunice.

HILLIAS: (As Eunice Hubbell, yelling) I hope they haul you in and turn the fire hose on you like they done the last time.

BRANDO: (As Stanley Kowalski, yelling) Eunice, I want my girl down here.

HILLIAS: (As Eunice Hubbell) You stinker.

(SOUNDBITE OF DOOR SLAMMING)

BRANDO: (As Stanley Kowalski, yelling) Hey, Stella. Hey, Stella.

VIVIEN LEIGH: (As Blanche DuBois, whispering) Do that...

HILLIAS: (As Eunice Hubbell) I wouldn't mix in this.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

GROSS: Elia Kazan, welcome to FRESH AIR. Let's start with "A Streetcar Named Desire." Now, you actually, really, discovered Marlon Brando for the stage version of that, which you directed before directing the film. Why did you want him to audition for the role in the stage version?

ELIA KAZAN: Well, there was no audition. I had produced a play with Harold Clurman where he played a part. And he played a - like, a five-, six-minute scene, and he was stupendous, and he was marvelous in it. And that was his audition. He didn't know it. But then, when we lost John Garfield, and I began to think who would - really would be good as Stanley Kowalski, I thought of Marlon and gave him 20 bucks to go up and see Tennessee Williams up at the cape.

I learned later, he hadn't showed up, but he'd hitchhiked and used the $20 to eat with. So - but anyway, Williams took to him immediately. He called me up, he was ecstatic. He was overwhelmed. And that was - that's all the audition there was.

GROSS: When I think of all the actors and all the people in general who have imitated Brando doing Stella - I mean, untold numbers of people - what went on when you were directing him in that scene?

KAZAN: In that scene?

GROSS: Yeah.

KAZAN: I just told him to get on his knees at the bottom of the staircase. But I didn't tell him what to do with his voice or how he should shout it. He just knew. But many, many things with him - many, many times with him, he was ahead of me, and as he understood what I said and understood it better than I said it. And I hardly had to tell him anything. Once I said, you fall on your knees, and he did. And that's all there was to it.

GROSS: How many takes did you do of that scene?

KAZAN: How many takes did I do? I think two.

GROSS: And you knew you had it.

KAZAN: Yeah. Well, you couldn't mistake it, could you, really?

GROSS: (Laughter).

KAZAN: That tone of voice - I mean, people have imitated it and shouted it. And, you know, it's been on comedy shows and everything. It's just - once in a decade, a voice like that comes out.

GROSS: Now, you directed Brando again three years later in "On The Waterfront." I have found out in your book that it was initially supposed to be Frank Sinatra in the role.

KAZAN: Yeah. He would've been damn good too, but not as good as Brando. I don't think anybody's as good as Brando. But Frank would've been very good. Frank comes from Hoboken, and he's a street kid too, and he's tough. And he would've been good. And he's tough the way Brando's tough. He's got a tough exterior, and knows what to do with his fists and so on. But he also has a very poetic and romantic side that comes out in his songs, of course.

Anyway, I was ready to do it with Frank. But one thing led to another in the contracting - in the contract, and also in Frank's schedule. He had to be somewhere at a certain time. I've forgotten the details of it. And we switched to Brando.

GROSS: Brando, in that movie, really has this combination of strength and vulnerability.

KAZAN: Right, Terry. You hit it.

GROSS: What'd you talk with him about when he took on the role - about what characteristics you wanted him to get in there?

KAZAN: It's just that I said, he's - keeps a tough front towards everybody, but he feels this guilt about Eva Marie Saint's brother terribly - that it kills him, and he can't get rid of it. And he really would like to be out of the gangster-hoodlum world - and then didn't like what they did to him because they humiliate him. The part Lee Cobb played constantly humiliated him, made him appear like a cheap kid. And I told him that he would resent that and not show it for a while, and then release it as the film went on.

GROSS: I want to play another one of the most famous scenes in movie history. And this is the I-could've-been-a-contender scene. Now, in your book, you're very self-effacing about it. You said that you've been highly praised for the direction of this scene, but the truth is, you didn't really direct it. It kind of directed itself. I don't truly believe that. So let's hear the scene, and then we'll talk about it.

KAZAN: I'll say one thing about it before you do.

GROSS: OK.

KAZAN: The scene is good for several reasons, but one reason is because it was beautifully written by Budd Schulberg. It's a perfectly-written scene and in a kind of a tough language that is on the - poetic in itself. That's all.

GROSS: And this scene is played by Marlon Brando and Rod Steiger.

KAZAN: Right.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "ON THE WATERFRONT")

ROD STEIGER: (As Charley Malloy) And that skunk we got you for a manager, he brought you along too fast.

BRANDO: (As Terry Malloy) It wasn't him, Charley, it was you. You remember that night in the Garden? You came down to my dressing room and said, kid, this ain't your night. We're going for the price on Wilson. You remember that? This ain't your night. My night? I could've taken Wilson apart. So what happens? He gets the title shot outdoors on the ballpark. And what do I get? A one-way ticket to Palookaville (ph). You was my brother, Charley. You should've looked out for me a little bit. You should've taken care of me just a little bit so I wouldn't have to take them dives for the short-end money.

STEIGER: (As Charley Malloy) Oh, I had some bets down for you. You saw some money.

BRANDO: (As Terry Malloy) You don't understand. I could've had class. I could've been a contender. I could've been somebody instead of a bum, which is what I am. Let's face it. It was you, Charley.

GROSS: There's a musicality in the way those two actors read their lines that is really something. Did you work with them on that?

KAZAN: No, I didn't. I didn't direct that scene much. I didn't direct that scene, really. By that time in the shooting schedule, both Rod and Marlon knew what they had. And then the lines, themselves, are so beautifully written. Instead of a bum, which is what I am - that's the way those people talk. They're perfectly-written lines. And Marlon naturally took to them.

GROSS: You have really taken pride in directing actors who are encouraged to ask questions about what they're doing.

KAZAN: Yes.

GROSS: What kind of questions did Brando ask you about this role - any questions?

KAZAN: Very, very little. I think we had a instinctive fraternity. I think we understood each other, almost from the word go, very well. And we would talk a lot about other things, but not a hell of a lot about the role. He - this role is written thoroughly. When he says taking dives, Palookaville, all that - and it's written very thoroughly and beautifully.

And I - he didn't need much instruction. I mean, I wasn't kidding in the book. I wasn't being falsely modest. I think I'm a damn good director and have been a damn good director. But in this scene, I didn't direct that scene much - very little. I just put them there and so on.

GROSS: A lot of the extras in "On The Waterfront" were actually longshoremen.

KAZAN: Right, and hoodlums.

GROSS: And hoodlums, yeah.

KAZAN: And fighters.

GROSS: So you had a bodyguard in the making of the movie.

KAZAN: I had a bodyguard six feet behind me at all times. Well, there were some rough characters all around me, and they were taking offense that we showed Hoboken, for example, for a bad place. And they were offended. (Laughter) I laugh at that. But anyway, they had civic pride. That's what made me laugh. I thought they had civic pride.

And - but nobody threatened me much. Once they - a fella came, and slammed me against the wall and was going to beat me up. But then the bodyguard and another friend named Brownie came up, and that was the end of that threat.

GROSS: Gosh, let's move on to another movie you directed. Now, we talked about how you really, basically, discovered Marlon Brando. You also really discovered James Dean. You gave him his first film role in your film "East of Eden."

KAZAN: Yeah.

GROSS: I find that kind of interesting in a way because they're both - they were both at the time young actors with this pent-up energy and alienation.

KAZAN: Yeah. That's it. Alienation's right. Pent-up energy's right, Terry. You've got it exactly right, especially - no, not especially - both of them the same way, same thing in both of them. Somehow that must have appealed to me because maybe I have pent-up energy and alienation, too.

GROSS: (Laughter).

KAZAN: I felt brotherly towards them.

GROSS: Would you describe the meeting with James Dean that made you realize he had something?

KAZAN: I went to see a play of his. And a friend of mine named Paul Osbourn had recommended him to me. And I went to see him in a play. He played a part of an Arab, a small part. And I didn't think much of him. But I thought just to please Paul, I'd ask him to come into Warner Bros. office.

And I went in there that day, and there he was, like a - I say in the book - like a pile of rags in the corner, all bent over, scrunched up. And so - and I thought, well - he didn't even get up, didn't look at me, didn't get up. And so I went in the office, and said, well, I'll make the son of a bitch wait a little bit. It'll do him good.

GROSS: (Laughter).

KAZAN: So anyway, finally I call him into the office, and he came in. And he didn't say anything. He was not a talker. So finally, he didn't say a damn thing. And I said, well. And he said, do you want to go for a ride with me on my motorbike? So I said, God, I hate motorbikes. I didn't say it to him, but I do hate motorbikes. I think they're a menace. I said, all right, Jimmy, well, let's go.

So I went downstairs, and he got his motorbike and unlatched it or chained it or whatever he did. And I got in the back. And he rode me around the middle of the city. And it was like he was showing that a country boy can defy the city and defy the rules of the city. He zigzagged in and out, in and out. I didn't want to ruin my relationship as a director by saying, Jimmy, I'm frightened; cut it out. I was frightened. But anyway, finally - we finally both lived.

GROSS: I want to play a scene from this movie. And this is a scene where - well, let me - for our listeners who haven't seen the movie in a long time, in East of Eden, there's a father played by Raymond Massey. And he has two sons. One son he favors. The son he doesn't favor is James Dean. And James Dean has worked really hard to endear himself to his father. He's invested money in bean futures in the hopes of making back money that his father lost. And it's his father's birthday. He's presenting him the money, but his father won't accept it. Here's that scene with Raymond Massey and James Dean.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "EAST OF EDEN ")

JAMES DEAN: (As Caleb Trask) That's for you. It's all the money you lost in lettuce business. That's for you, and I made it for you.

RAYMOND MASSEY: (As Adam Trask) Cal, you will have to give it back.

DEAN: (As Caleb Trask) No. I made it for you, Dad. I want you to have it.

MASSEY: (As Adam Trask) You'll have to give it back.

DEAN: (As Caleb Trask) Who? I can't give it - to who?

MASSEY: (As Adam Trask) To the people you got it from.

DEAN: (As Caleb Trask) British purchasing agency - I can't give it back to them.

MASSEY: (As Adam Trask) Then give it to the farmers you robbed.

DEAN: (As Caleb Trask) We didn't rob anybody. That was - we paid two cents a pound - two cents over market for that stuff.

MASSEY: (As Adam Trask) Cal, I sign my name, and boys go out, and some die. And some live helpless without arms and legs. Not one will come back untorn. Do you think I could take a profit from that? I don't want the money, Cal. I couldn't take it. I thank you for the thought, but...

DEAN: (As Caleb Trask) I'll keep it for you. I'll wrap it up, and we'll just keep it in here. And then we'll...

MASSEY: (As Adam Trask) I'll never take it.

GROSS: There's a great part right after that where you can't tell whether James Dean is going to hug or slug his father.

KAZAN: That is good, yeah.

GROSS: Now, you write in your book that there really was a tension between James Dean and Raymond Massey. And you...

KAZAN: Yes, there was.

GROSS: You basically tried to exploit that in the movie.

KAZAN: They didn't like each other, and especially Ray Massey. He couldn't stand Dean. He just couldn't - hated to play scenes with him. And I didn't - I guess I did exploit it because I didn't do anything about curing it or easing it. And you see how much he resents him in the scene, in the role. But also, he did in life. It served my purposes to not do anything about it. I didn't egg them on to each other, but I didn't do anything to heal it.

GROSS: You know, in the clips that we just heard - we heard from Brando and from Dean, two very different actors in that Brando you describe as an actor with a lot of technique, Dean as an actor who had virtually none at least at the time you directed him. How does that change you as a director, depending on whether you're working with someone who has a lot of technique or someone who's more of a natural and doesn't have that technique?

KAZAN: You adapt to what each one is. You - I talked more to Jimmy than I ever did to Marlon. I took him aside. And finally when I felt he was disturbed in life by what was happening in his own personal life, I moved him into a dressing room on the Warner Brother lot, and I took the dressing room directly facing it so that I'd always be at hand. I was like a father to him or a big brother to him and looked after him.

Every morning, I'd call him out and see what he - condition he was in, whether he had a miserable night or not. And then I had to several times stop him from owning a horse or a motorbike or whatever, you know? So it became a very different, more intense, more particular relationship. With Marlon, I didn't have to do anything like that.

GROSS: We're listening back to my 1988 interview with director Elia Kazan. We'll hear more after a break as our 30th anniversary retrospective continues. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. We're continuing our 30th anniversary retrospective featuring interviews from our first two years. Let's get back to my interview with director Elia Kazan, which was recorded in 1988 when he published his autobiography.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

GROSS: Now, your autobiography is really the first time you've publicly addressed why you named names during the HUAC hearings...

KAZAN: That's right.

GROSS: ...In the 1950s. And I was wondering why you're ready to talk about it now. For years when you were interviewed, people would ask you about it, and you wouldn't - you just wouldn't want to talk about it. People have written in their autobiographies how they felt about you naming names, but you've never publicly addressed it till now.

KAZAN: The reason I felt OK about it now was that I always hesitated to do it because I wanted to make it part of my whole life - in other words, so that everything that happened before had some way or other, not for others but for me, led up to it. And for example, I put in the scene where the man from Detroit came and attacked me in front of my group. I put in the scene where we were trying to do a picture in Mexico, and the Communists there prevented us from doing it for their reasons. I put in other references so that by the time I got to it, you felt I'd been through certain experiences that would at least motivate me, if no one else, into doing that.

GROSS: Well, my understanding is that you decided to talk for two reasons. One was that you felt that when you were a member of a communist group, that the actors were really exploited by the party and also that you didn't want to give up your career, that you'd really thought about it, and you decided that writers could write while they're in prison, but directors couldn't do anything in prison. And directors couldn't do anything if they were shut out of the industry.

KAZAN: Yeah, something like that but not exactly. I thought - you know, I love my work, and it means everything to me. It's my whole life really except my family. My family and my work - those are the two things I have. And I thought, why should I give up my career for something I don't believe in? I don't believe in it. And if people who are communists are still going to attack me and still feel that they don't want to talk about it, I also feel that - then hell with them.

I also feel that any country - for example England and France - any country has the right to investigate something like what was going on in this country. And the only trouble with our committee was that two of the fellows lied to me. They told me that I was in an executive session where I'd be talking privately. And it turned out they were running with the news to Hollywood gossip columnists and everything else. So I lost my respect for them, too.

GROSS: There are many people who have been in your life who've never forgiven you for naming names and have certainly never forgotten it. Did you expect this decision to stay with you throughout your life in the way that it has?

KAZAN: No, you have to believe me, Terry. I don't give a darn about that. I only am concerned really whether I respect myself. I thought a very long time about it. I thought very hard about it. And I did - I made a difficult choice. Both sides, both ways would have been difficult for me.

GROSS: Have you had second thoughts about the choice you made?

KAZAN: Not really, no. I think I wish they'd done it. I wish they'd name me. I think if the whole bunch of us had come out and said we did have a communist cell, so what, I don't think they would have been worse off. I think it would have been - clear the air. But of course except for the three I did talk to, none of - they didn't do it.

GROSS: Director Elia Kazan recorded in 1988. He died in 2003 at the age of 94.

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

In 1988, I also spoke with actor Kirk Douglas, who helped break the Hollywood blacklist when he produced the 1960 film "Spartacus," which he also starred in. Douglas decided to hire a blacklisted writer, Dalton Trumbo, to write the screenplay for "Spartacus."

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

GROSS: Dalton Trumbo was writing it under a pseudonym like he was writing all of his screenplays at the time because he was blacklisted. And you insisted that for this movie he actually use his real name. Did you think that the time was right where you could say, this is Dalton Trumbo who wrote the movie and where it would actually be accepted, that the time was right to break the blacklisting and have it be accepted at least in part of Hollywood?

KIRK DOUGLAS: Well, I'm not so sure. I did it rather impulsively. I don't think I was aware until a couple years later as I reflected upon it. And like, you know, I explain in my book, I began to see, you know, the significance of it. What bothered me when I did "Spartacus" was the hypocrisy in Hollywood that these people, some of them who spent a year in jail for a crime that was never very clearly stated, I mean were denied using their talents except behind the scenes. Studio heads would look the other way while a lot of these unfriendly 10 writers would be writing scripts for very little money.

So it was so hypocritical that it annoyed me to the extent that I said, well, what happens - we had a discussion of, whose name are we going to put on the script of - on the screen of "Spartacus"? And suddenly I said, well, what happens if I put Dalton Trumbo's name on? And they said oh, Kirk, you're - they say, oh, you're going to get out of the business and all that. I said no, to hell with it. I'm going to do it.

And the next day I left the past. Dalton Trumbo hadn't been on a set in ten years. I left the past for Dalton Trumbo, no Sam Jackson. Of course even Sam Jackson we wouldn't have allowed on the set. Somebody might've recognized him as Dalton Trumbo.

GROSS: That was his pen name for this movie.

DOUGLAS: Yes. And from then on - I'll never forget when Dalton Trumbo walked on the set, came over me and says Kirk, thanks for giving me back my name. There were people who - I got letters from different organizations. Hedda Hopper attacked me. But the sky didn't fall in. And after that - a few months after that, Otto Preminger announced that Dalton Trumbo was going to be writing this script, and the blacklist was broken.

GROSS: We'll hear more of my interview with Kirk Douglas, and we'll hear my 1988 interview with director Sidney Lumet in the second half of the show as we continue the FRESH AIR 30th anniversary retrospective. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF ALEX NORTH'S "MAIN TITLE")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Let's get back to our 30th anniversary retrospective featuring some of our favorite interviews from our early days. We'll pick up where we left off with my 1988 interview with actor and producer Kirk Douglas. He was one of Hollywood's biggest stars of the 1950s and '60s and was also one of the first actors to run his own production company. He's also the father of actor and producer Michael Douglas.

Kirk Douglas made about 75 films, including "20,000 Leagues Under The Sea," "Paths Of Glory," "Spartacus," "Lonely Are The Brave," "Gunfight At The O.K. Corral" and "Lust For Life," in which he played painter Vincent Van Gogh. Douglas is the son of poor, illiterate Russian-Jewish immigrants. Our interview was recorded when his autobiography was published.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

GROSS: You had starred in "The Vikings." And you write in your new autobiography, "The Rag Man's Son," that, after starring in "The Vikings," you thought, that's it - no more epics for me. And then you go and turn around, and actually produce one of the real big epics, "Spartacus." Why did you want to make an epic?

DOUGLAS: Well, I didn't want to make an epic. And one of the first things I said to my group - I said, look, if we do this picture "Spartacus," let's make it as if it were a small picture. And to me, if you look at "Spartacus" again, you will find that the characters dominate the background. Most pictures, "Ben-Hur" and all that, the background is so enormous.

But in "Spartacus," Olivier, Laughton, Ustinov, Jean Simmons - the characters are stronger than the background. And that's what I tried to do. In spite of the fact that it was an epic picture, I wanted the characters to be - for them to be larger than life.

GROSS: You mentioned the characters and some of the actors. You ended up casting Jean Simmons in the role of Spartacus' lover and the woman who he has a baby with. And initially, you didn't want to cast her because she's British, and you thought that that would ruin the linguistic pattern of the movie. And I'd love for you to explain what you meant by that.

DOUGLAS: Well, I have a very simple - for example, when I did "The Vikings," all the Vikings are Americans. We have a rougher pattern of speech. The English have a more elegant pattern of speech. So that makes it work. In Spartacus, you'll notice that all the aristocratic Romans are English.

GROSS: That's right. They're great...

DOUGLAS: The slaves...

GROSS: ...Stage actors (laughter), great British stage actors.

DOUGLAS: The slaves, like myself, were Americans.

GROSS: Not only that, ethnic - right? - Jewish, Italian. You, Jewish, Tony Curtis, Italian - no, Tony Curtis is Jewish, too, actually. Isn't he?

DOUGLAS: That's right.

GROSS: Yeah, that's right. (Laughter) I always forget that (laughter).

DOUGLAS: But it doesn't matter, you see. It's just that Americans have a rougher speech pattern. For example, I often think that Shakespeare very often is better played in - when it's done in the United States because those beautiful lines take on a rougher quality that I think Shakespeare really intended it to...

GROSS: So the slaves have the rough quality.

DOUGLAS: That's right.

GROSS: And the Romans have the more genteel, educated, refined sound.

DOUGLAS: Exactly. Of course, "Spartacus" - you picked on a picture that plays a big - is a big section in my book because so much happened during the making of "Spartacus." The most historical event was the breaking of the blacklist.

GROSS: Since we're talking about "Spartacus," let me play a clip from the movie. And this was toward the end of the first half of the film. Remember, this movie had an intermission (laughter). And Spartacus and many other slaves have escaped from slavery. And after they've escaped, many of the slaves are just drinking wine. They're having Romans fight each other as if the Romans were slaves. And Spartacus is saying, what are you doing with your lives? You should be doing something more productive. And he suggests that they actually fight the Roman Empire.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "SPARTACUS")

DOUGLAS: (As Spartacus) Have we learned nothing? What's happening to us? We look for wine when we should be hunting bread.

NICK DENNIS: (As Dionysius) When you've got wine, you don't need bread.

(LAUGHTER)

DOUGLAS: (As Spartacus) We can't just be a gang of drunken raiders.

DENNIS: (As Dionysius) What else can we be?

DOUGLAS: (As Spartacus) Gladiators - an army of gladiators. There's never been an army like that. One gladiator's worth any two Roman soldiers that ever lived.

JOHN IRELAND: (As Crixus) We beat the Roman guards here, but a Roman army is a different thing. They fight different than we do, too.

DOUGLAS: (As Spartacus) We can beat anything they send against us if we really want to.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #1: (As character) It takes a big army for that, Spartacus.

DOUGLAS: (As Spartacus) We'll have a big army. Once we're on the march, we'll free every slave in every town and village. Can anybody get a bigger army than that?

DENNIS: (As Dionysius) That's right. Once we cross the Alps, we're safe.

IRELAND: (As Crixus) Nobody can cross the Alps. Every pass is defended by its own legion.

DOUGLAS: (As Spartacus) There's only one way to get out of this country - the sea.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #2: (As character) What good is the sea if you have no ships?

DOUGLAS: (As Spartacus) The Cilician pirates have ships. They're at war with Rome. Every Roman galley that sails out of Brundisium pays tribute to them.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #1: (As character) They've got the biggest fleet in the world. I was a galley slave with them. Give them enough gold, they'll take you anywhere.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #3: (As character) We haven't got enough gold.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #4: (As character) Take every Roman we capture and warm his back a little. We'll have gold, all right.

(LAUGHTER)

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR #1: (As character) Spartacus is right. Let's hire these pirates and march straight to Brundisium.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTORS: (As characters, screaming).

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: Well, they get their army. And you, as Spartacus, lead them against the Roman army. There is a scene at the end that is a mass crucifixion. And you are one of the many actors on the cross (laughter) at the end of the movie. And I'd really like to know how you were attached to the cross so that you could hang there without really hurting yourself.

DOUGLAS: Well, as a matter of fact, playing that scene, we learned an awful lot about crucifixion. We learned that it would be impossible to be crucified the way, very often, you see the crucifixion. You know, the body would sag right down. But to make our scenes effective, it was very easy. Every cross had a bicycle seat. It just kept the body up high enough so that you wouldn't be sagging down in a very unattractive position.

GROSS: OK, so that's the secret. You started off in your first movie playing someone who was pretty weak in the film "The Strange Love Of Martha Ivers."

DOUGLAS: That's right.

GROSS: And you went on to become a character who was seen as very strong. In fact, you were - mentioned that Elia Kazan refers to you in his autobiography. And I'd like to read one of the things that he says when he was making the film "The Arrangement," based on his best-selling novel. You wanted to be in the film. And he cast you in it, although he says he - there was something about the role that he thought Marlon Brando would've been better for.

And Elia Kazan writes, there was one problem with Kirk. Eddie, the character, has to start defeated in every personal way. The film rests on how basic and painful his initial despair is. Kirk has developed a professional front, a man who can overcome any obstacle. He radiates indomitability. Marlon, on the other hand, with all his success and fame, was still unsure of his worth and of himself. Acting had little to do with it. It was all a matter of personality.

Did you ever think of yourself that way, as just radiating indomitability, and that affecting the kind of roles that you could or could not do well?

DOUGLAS: Working with Kazan in "The Arrangement" was a wonderful experience. He's a great director. But I disagree with him completely. When I did "Lust For Life," which I consider one of the most intriguing roles that I've played, I played a man completely unsure of himself. As a matter of fact, I sometimes tell my fellow actors that no one can play weakness better than I, starting with the very first movie that I did, "The Strange Love Of Martha Ivers."

And then when you go to a character like "Lust For Life," I remember the first time we showed that - and I described this incident in my book where John Wayne was drinking at a party after a showing. He was very annoyed. He motioned me, brought me out on the balcony and said he was very annoyed. He said, Kirk, how can you play such a sniveling, weak character? I said, well, John - I said, well, you know, I'm an actor. It was an interesting role. I wanted to play it. No, no, he says. Kirk, we've got to play tough, macho guys. And he was really upset that I would be playing such a weak character, although most people, I think, think of me - the last movie I did with Burt Lancaster was called "Tough Guys" - as sort of a tough guy.

But I loved to play parts or try to find parts with different dimensions. You see, Terry, if I play a strong man in the film, I look for the moments where he's weak. And if I play a weak character, I look for the moments where he's strong because that's what drama's all about - chiaroscuro, light and shade.

GROSS: I want to ask you something about you physically, in terms of your acting. People think of you. They think of your voice. Physically, they really think of the dimple in your chin. And when you started acting, was there ever a time where that was seen as a disadvantage? Did anyone ever try to cover that up with makeup?

DOUGLAS: Oh, yeah. The first time I came to Hollywood, you know, and they're looking at this Broadway actor - and they did. They filled it up with putty.

GROSS: Oh, really?

DOUGLAS: Yeah. It had to be an awful lot of putty because I don't have a dimple in my chin. I have a hole in my chin. And it annoyed me. I said, look. I just pushed the putty out. I said, look; this is what you get if you want it. I'm not going to change it. So let me know if this is what you want, or I'm going back to New York. And since then, I've never - you know, it's a part of me.

GROSS: So you never let them actually shoot you with the putty in your chin?

DOUGLAS: Oh, I would do that if there was a real reason where I wanted someone to have, like, a big, lantern jaw and covering up this dimple on my chin would give me that effect. I would do it if the reason was to play a certain character or it's covered up when you have a beard. I mean I do whatever I feel you have to do to play the character, not for, you know, vanity sake. I am what I am. I can't change that.

GROSS: My interview with Kirk Douglas was recorded in 1988. He turned 100 in December. After a break, we continue our 30th anniversary retrospective with another 1988 interview with film director Sidney Lumet, who made "Dog Day Afternoon," "Serpico" and "12 Angry Men." This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF KEVIN EUBANKS' "POET")

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. We're continuing our 30th anniversary retrospective with a 1988 interview with director Sidney Lumet, whose movies include "12 Angry Men," "Long Day's Journey Into Night," "The Pawnbroker," "Fail Safe," "Serpico," "Murder On The Orient Express," "Dog Day Afternoon," "Network," "Equus," "The Wiz" and "Prince Of The City." When I spoke to him, he'd already directed about 40 films.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

GROSS: Let's talk a little bit about your first film made in 1957, and this was "12 Angry Men," a courtroom drama. You had before that been directing television - live television dramas. Was this a good transition to make since it was basically a one-set movie? It's a courtroom drama. It's a jury drama. They're in the deliberation room most of the movie. Was that a good place to start?

SIDNEY LUMET: It was good, and it was a great problem, except that I was dumb enough not to know what the problem was. It was very difficult to shoot a movie in one room. That never occurred to me.

GROSS: Really?

LUMET: (Laughter) I just plunged in with complete ignorance knowing what I wanted to do with camera, knowing that I could make the camera a good interpretive part of the movie itself. And I may have felt enormously secure at the confinement of it because my background, as you say, had been live television and theater. So the idea of staging something in one room was something that came very easily to me.

GROSS: Well, the movie starred Henry Fonda and Lee J. Cobb. Fonda is the only juror initially convinced of the defendant's innocent. Cobb is the last holdout. I want to play a clip from this movie, "12 Angry Men."

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "12 ANGRY MEN")

HENRY FONDA: (As Juror 8) Maybe she honestly thought she saw the boy kill his father. I say she only saw a blur.

LEE J COBB: (As Juror 3) How do you know what she saw? How does he know all that? How do you know what kind of glasses she wore? Maybe they there were sunglasses, or maybe she was farsighted. What do you know about it?

FONDA: (As Juror 8) I only know the woman's eyesight is in question now.

GEORGE VOSKOVEC: (As Juror 11) She had to be able to identify a person 60 feet away at night without glasses.

FONDA: (As Juror 2) You can't send someone off to die on evidence like that.

COBB: (As Juror 3) Oh, don't give me that.

GROSS: It's a heck of a cast. In addition to Fonda and Lee J. Cobb, you have Jack Warden, Jack Klugman, E.G. Marshall, Ed Begley. You directed them your first time out on film. And you've since directed Paul Newman and younger actors like Al Pacino and Treat Williams. Is there a difference in the acting styles of the actors who you were directing in the '50s and the actors who came of age in, say, the '70s?

LUMET: Not really, Terry. They - the basic craft of acting has, in the United States, has been set for some years, really, even before the method came in. Basically people like Fonda worked out of a profound sense of truth. In fact a man like Fonda didn't know how to do anything falsely and used himself. He used himself brilliantly. Both of those elements are foundations of the method. And even though he wasn't called a method actor in the sense of having studied the method, he basically worked out of that as most good actors did.

GROSS: Do you think of yourself as a method director?

LUMET: No. I become the kind of director that becomes whatever his actors need. When we did "Long Day's Journey Into Night," there was a perfect example. Kate Hepburn has a very specific way of working her own technique. Ralph Richardson is a prime example of British technique, which is primarily from what we call the outside in. Dean Stockwell works completely method from the inside out. And Jason has his own glorious world of creating something from inside himself. And heaven knows where it comes from.

GROSS: You directed Al Pacino in two of his first big movie roles, "Serpico" and "Dog Day Afternoon." I want to play a short scene from "Dog Day Afternoon," and maybe you can tell me what you think Al Pacino needed when he was getting started. This is a scene from the very opening of the movie when Pacino walks into a New York bank. And he holds it up, and he wants the money to buy a sex change operation for his lover.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "DOG DAY AFTERNOON ")

AL PACINO: (As Sonny) All right, freeze. Nobody move.

JOHN CAZALE: (As Sal) Get over there.

PACINO: (As Sonny) OK, all right, get away from those alarms. Come on. Now get in the center. He moves, take his head off. Put the gun on him. Get out of the center.

GARY SPRINGER: (As Stevie) Sonny, I can't do it, Sonny.

PACINO: (As Sonny) What?

SPRINGER: (As Stevie) I'm not going to make it, Sonny.

PACINO: (As Sonny) What are you talking about? Put it on him.

SPRINGER: (As Stevie) I can't do it, Sonny.

PACINO: (As Sonny) Sal, Sal.

CAZALE: (As Sal) What?

PACINO: (As Sonny) Where are you? He can't make it.

GROSS: It's an interesting performance because Pacino is so manic in it and yet so insecure and incompetent at robbing this bank. What did he need when he was getting started? You were talking before about giving actors what you think they need.

LUMET: Primarily, what he needed was a - this is going to sound like an anachronism, and it was. He needed a great sense of freedom and a great sense of restriction. That - the creation of the character is really Al's own. He understood something about that man that is irreplaceable.

For example, there's a scene toward the end of the movie where he's talking to his female wife, his real wife, on the telephone, trying to decide what to do. And the scene is extraordinary in the sense that it requires a level of emotion that I've seen very rarely in movies. We did the scene in one take because I - with two cameras because I didn't want him to have to repeat that emotion over and over again. And when he finished it the first time, it was wonderful.

And without waiting an instant, I didn't even cut the camera. So I said, Al, go again. And he looked at me like I was crazy because he was exhausted, he was spent. And I said, right now, action. And what I was driving at was that he had reached such a height at the end of the first take, such an emotional peak. But that's really where I wanted the scene to begin.

GROSS: That's an interesting story. Now, you mentioned there that he really did it very well on the first take, but you wanted that emotional spent-ness (ph) to be the starting-off point, so you had him do it again. Now, you're really known for doing a lot of performances on first and second takes, for not going for a lot of takes. I wonder if you ever run into conflicts where there's one actor in a scene who works really well on that first or second take, and another actor who sees it as their style to go for 15 or 16 takes until they really get it perfect. What do you do if you run into that?

LUMET: I have run into it. And so far - if there were a piece of wood around the studio, I'd knock on it.

GROSS: (Laughter).

LUMET: But so far, I've been able to convince the 15- or 16-take actor that the other works. The early takes are not imperfect. They are usually the freshest, truest. The repetition, I find - and I think, for most good actors, the repetitions tend to become mechanical. One doesn't find more truth in it as it goes on.

Now, that partially has to do with the way I work because, as you know, or may know, I rehearse very heavily. I rehearse two to three weeks, depending on the complexity of the characters, before we begin. And those rehearsals are conducted like theater rehearsals, in the sense that people learn their lines completely, are working without scripts. They're completely blocked, to the degree that we're having run-throughs by the end of it.

GROSS: Now, you really came from a theater family. Your father acted in the Yiddish theater. Did having a father in the Yiddish theater help you love performance, drama?

LUMET: Absolutely, absolutely. The peculiar thing is, there's a sort of strange, post-World War II American problem. Children don't - children of actors, and writers and directors tend to be nervous, and they're terrified of going into their parents' work. And yet, the history of the world is going into your parents' work. I mean, in England, in the Redgrave family, Natasha, now, is the fourth generation of that family that's become an actor.

And fortunately, it's beginning to make some sense in America. Last year, I - two years ago, I did a movie with Jane Fonda and Jeff Bridges. And I had worked with both of their fathers. I'd worked with Henry, and I'd worked with Lloyd. And I found that very moving.

GROSS: We're listening back to my 1988 interview with director Sidney Lumet. We'll hear more after a break, as we continue our 30th anniversary retrospective. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's continue our 30th anniversary retrospective and get back to my 1988 interview with director Sidney Lumet.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

GROSS: I want to play another short scene from another movie you directed. And this is "Network," which came out in 1976. Peter Finch won a posthumous Academy Award for his performance in this. And in this scene, he plays a lunatic, self-styled, messianic broadcaster who is basically preaching his editorial.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "NETWORK")

PETER FINCH: (As Howard Beale) I don't know what to do about the depression or inflation and the Russians and the crying in the street. All I know is that first you've got to get mad. You've got to say, I am a human being, dammit. My life has value.

So I want you to get up now. I want all of you to get up out of your chairs. I want you to get up right now, and go to the window. Open it, and stick your head out. And yell, I'm as mad as hell, and I'm not going to take this anymore.

GROSS: And right after, as he's doing that editorial, people all over Manhattan in high-rise apartment buildings open up their windows, stick their heads out and start yelling that they're mad as hell, and they're not going to take it anymore. I thought that scene really tapped into something. And for me, what it tapped into is the fear - is that in Manhattan, there's so many high-rises filled with so many people with all this pent up anger.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: And if it was ever let loose, we'd really be in big trouble.

LUMET: Well, Paddy Chayefsky had that unique ability to tap the most fundamental truths in people, in the individual characters and also in terms of a - in terms of his own - the situation that he was observing. Did you ever see a picture that he wrote called "Hospital?"

GROSS: No, I didn't.

LUMET: Well it's hilarious, as "Network" is, with fundamentally a deeply serious idea behind it. And he did it in that, too. He's - I miss him every day.

GROSS: "Network" was one of your many movies that was shot in New York locations. Now, I think you were really one of the first directors to actually do location shooting in Manhattan.

LUMET: Yeah, Kazan first and me right behind him. But at that time, it wasn't fashionable at all. It was very difficult to put together more than one good movie crew because there was that little work going on here. Also it coincided clearly with the kind of picture we were doing, which were usually very realistic pictures, pictures that benefited visually from being done on location.

GROSS: Sidney Lumet recorded in 1988. He died in 2011 at the age of 86. Tomorrow we'll continue our 30th anniversary retrospective featuring interviews from our early days. We'll hear a 1987 interview with Ronnie Spector of the girl group the Ronettes and 1988 interviews with Otis Williams of The Temptations and Ben E. King, who was a lead singer with the Drifters and had the hit "Stand By Me." I'm Terry Gross. I hope you'll join us.

While we continue our on-air celebration of our 30th anniversary, there's a lot of sadness back in the FRESH AIR offices. Our longtime colleague and friend Dorothy Ferebee died late last week after a long illness. She was 68. Dorothy was our administrative assistant from 1990 until she retired last year. One of her jobs was answering listener questions, so it's possible you spoke with her on the phone or received an email from her.

We loved Dorothy because she had a big heart, a sly sense of humor, and she was a pretty good mimic. You could always tell where she stood on an issue with just one glance at her face, but she had no patience for phonies. She had the back of everyone she cared about, and that was a lot of people - her colleagues like us, her children, grandchildren, and cousins, her friends and members of her religious community in which she was a leader. She always seemed to be helping someone by offering guidance, practical assistance or comfort.

She loved that we received so many new books at FRESH AIR because she collected books by and about African-Americans. In 2003, she became an author herself. Her book "How To Create Your Own African-American Library" was an overview of essential books including slave narratives, biographies, children's stories and classic novels.

Over the past 30 years, I've done a lot of obits on FRESH AIR, but this is the first time I've had to mark the passing of one of our own. We send our deepest condolences to Dorothy's daughter Kenesah, her son Brahim, who we watched grow up, and their children. We'll close with music Dorothy loved by the band the Buena Vista Social Club. Rest in peace, Dorothy.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "MURMULLO")

BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB: (Singing in Spanish).

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.