Contributor

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on April 15, 1998

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: APRIL 15, 1998

Time: 12:00

Tran: 041501np.217

Type: FEATURE

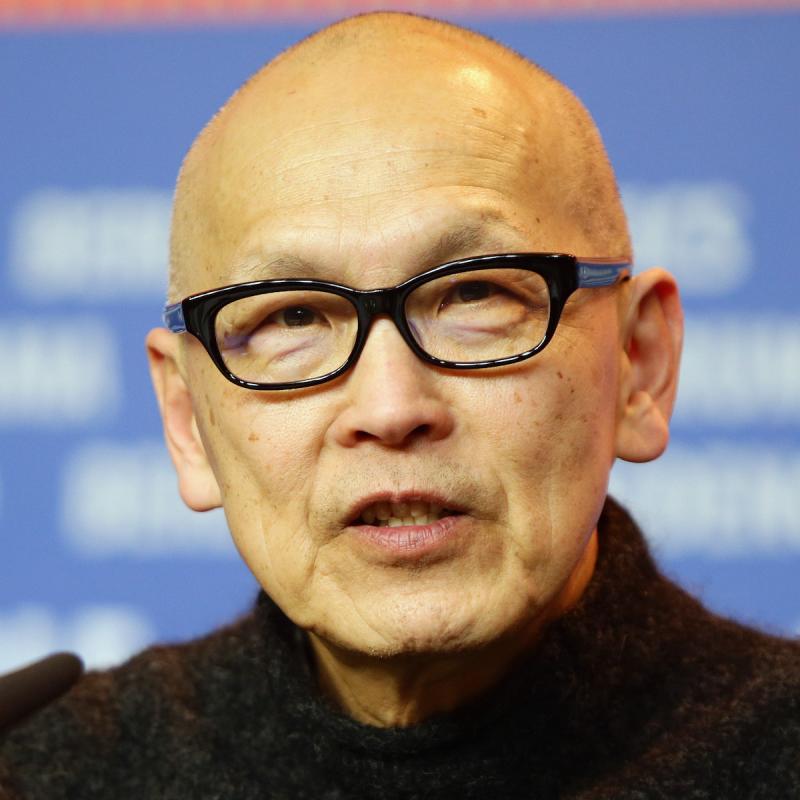

Head: Wayne Wang

Sect: News; International

Time: 12:06

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

My guest Wayne Wang is the director of the films "Joy Luck Club," "Smoke," "Dim Sum," "Eat a Bowl of Tea," and "Chan is Missing." He was born in Hong Kong in 1949 and first came to America at the age of 18 to study film.

Last summer, as Hong Kong was about to revert from British colonial rule to Chinese rule, Wang returned to Hong Kong to shoot his new movie "Chinese Box." The screenplay uses this political transition as the backdrop for the personal transformations that the characters undergo. A little later, the film's star Jeremy Irons will tell us about his experiences on location.

Chinese Box also stars Gong Li (ph), best known here for her role in "Raise the Red Lantern;" Maggie Chong (ph), a Hong Kong movie star; and Reuben Blades (ph).

I asked Wayne Wang why he wanted to be in Hong Kong making a movie during the transition to Chinese rule.

WAYNE WANG, FILMMAKER, "CHINESE BOX": I was born and raised in Hong Kong and I lived there until I was 18. And even after I left for college, I'd go -- I went back there to work. My wife was living there for a while. My parents lived there until 1989 -- 1989, yeah. And I, you know, really spent a lot of time there after I'm gone.

So in a way, it's my -- it's my birth home. In a way, it's a city that's very close to me. And during this period of the last six months, when it's about to be handed over to China, I just felt that I wanted to go there, make a movie, and understand what, you know, my feelings are about, you know, this city that's about to change forever.

GROSS: Do you think that making a movie in Hong Kong helped you understand what your feelings were about the transition?

WANG: I think it did. I mean, otherwise I would probably not deal with it so closely and not deal with it on a day to day level so much, and certain things wouldn't hit me as immediately, you know, 'cause one of the things, as I realized through the process, is that I was -- and this is something that I suppressed -- that I was really brought up as a colonial subject; that I was actually the first generation of Chinese who, you know, went to Hong Kong, was born in Hong Kong, and really wanted to be very Westernized.

In this case, you know, when I was in high school, I wanted to be, you know, more English. And that's very much part of me that I've kind of suppressed in my subconscious. And through these six months working on the film, and making the film and understanding what this transition means to me, a lot of that came back.

So -- and you know, because -- because I had to deal with this issue day to day there while were making the film.

GROSS: What do you see as being the more British sides of yourself?

WANG: I actually had forgotten that even when I first went to California, I spoke English with a British accent and people used to laugh at me. You know, there are certain taste that's very much part of my subconscious. I mean, I remember eating sardine sandwiches with big slabs of butter and very thin white bread. I mean, that's classic sort of English sandwiches.

GROSS: And they shouldn't be proud of it.

LAUGHTER

WANG: And they shouldn't be proud of it. And they're probably all dead by now, you know, eating all that butter. So anyway -- and also, growing up with English television and English rock and roll. I mean, you know, things like that, you know, were very much part of my growing up.

GROSS: What are some of the parallels between the love story that you created for the movie Chinese Box and the story of Hong Kong's transition from British to Chinese rule?

WANG: I guess the one parallel is that, you know, basically in the end, there are a lot of things that you're aware that you don't know. I think as much that you try to dig deep into a love relationship or dig deep into Hong Kong and this whole changeover -- the politics, the economics, whatever -- I think the more you find out, the more you know, you're also quite aware of what you don't know.

GROSS: One of the photojournalists in the movie says: "what can you photograph in the story about Hong Kong's reversion to Chinese rule? The real story is the dealmaking and that happens behind closed doors." I'm wondering how the reality of the Hong Kong story compared with what you were expecting visually.

WANG: Well, the stuff behind closed doors, we couldn't shoot. I mean, I'm sure there was a lot of interesting things I wanted to shoot, but I could not have access to things behind closed doors. I was hoping also for more dramatic things to happen visually in Hong Kong. I was hoping that, as Reuben Blades in the film says, you know, "more heads to be crushed," you know, during this -- this period.

You know, but -- but, you know, the Chinese, the English, and the people of Hong Kong all wanted this transition to be very smooth. They all wanted it to be a big celebration. Everybody was in a sort of denial in a way and just made sure that, you know, nothing would happen during this period.

So in the end, that was OK because I -- I, you know, was resigned to the fact that I didn't want to push any drama when there wasn't any drama; that you know, the things that were happening was much more subtle. And so, I sort of worked it in in a more subtle sort of textual way, rather than in the sort of blatant, you know, dramatic way.

GROSS: Was part of you truly hoping for a brutal crackdown so you'd have something dramatic to photograph?

WANG: Oh, I would say selfishly as a filmmaker, there was a part of me that was hoping for that. But you know, that's -- I mean, I'm very aware of how selfish that is and how horrible that is. But at the same time, I'm also very happy that nothing really happened.

Well, I'm torn about that. I'm really -- in a way, you know what, I was very frustrated that actually the people of Hong Kong didn't actually do something about, you know, all these things happening to them.

For example, you know, a lot of, you know, human rights things were taken away from them -- blatantly taken away from them. And nobody really, you know, did very much. There's your usual, you know, politicians and active people trying to protest against it, but nothing happened.

So I was kind of frustrated by that, and I created fictional students who committed suicide in protest of some of those things. So in that -- that's my own personal frustration in terms of the whole apolitical side of Hong Kong and the passivity side of Hong Kong when it comes to politics, and things such as human rights and what not.

GROSS: There's footage in your movie of the Chinese troops marching into Hong Kong. And I'm wondering if that's footage that you shot or whether that was stock footage from, you know, news programming.

WANG: There was a mix of stock footage and also real footage that we shot. We had a camera team that was out at the border covering the tanks coming in and all that. But some of it was not -- some of it was very good. Some of it was not good enough, so we used a mix of the two.

GROSS: What did you experience as the Chinese troops came in? Were you there watching it? And what did you feel in your stomach?

WANG: For me, I mean, I -- I keep remembering the Tiananmen Square. I mean, I know it's a very dramatic, very drastic sort of connection, but that's the image that I had. You know, because those images of the tanks rolling into Tiananmen Square was so powerful and so horrible.

So in my mind, you know, that was what was coming up, even though, you know, nothing happened. But you know, that's sort of something that's typically Chinese in that they insisted on that happening on, you know, the night of the changeover. They insisted on that show of power, because they wanted people back in China on TV to see that.

So, for that matter, I felt it was sort of done in kind of bad taste.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Wayne Wang and his new movie Chinese Box is set in Hong Kong at the time of its transition from British to Chinese rule.

What were some of the sights that you remember from your childhood in Hong Kong, that you wanted to include in your new movie?

WANG: Well, one of the things that -- that I remember very clearly as a child is that I wandered the streets around my neighborhood a lot, and there were a lot of open-air markets. And the -- and also, you know, sometimes my mother would bring me to the open-air markets. And you know, the Chinese really, you know, shop actually two times a day for very fresh fruit. You know, this is also before supermarkets, before frozen food and all that.

So -- but still, it's a tradition and a custom where you buy chicken, you go out, you, you know, see a live chicken and then you see it get, you know, get -- get killed right there, and then you'd buy it fresh. So that kind of imagery is very, very much in -- in my memory.

And when I made this film, and when Jeremy Irons' character found out that he was dying, you know, we had several scenes where he went out in the streets to the open market and saw kind of, you know, the day to day kind of death that was going on on all levels of life, so to speak. And he's trying to understand what it means for himself.

So, those images are very strong in my mind.

GROSS: Well, those images are actually pretty graphic. I mean, there's images of a -- of a heart still beating in a chicken's body after the chicken is cut open and slaughtered.

WANG: Mm-hmm. Yeah. That's something that I think even as a child when I saw it, it was really amazing. I remember the first time I saw it, I just -- I couldn't understand it, which is this fish that's cut open, literally, you know down the middle, and five minutes later, the heart is still beating really, really strong.

So -- and there's something -- you know, it's like, you know, death -- life after death, and it just keeps on going.

GROSS: Gee, was it a fish and not a chicken that I was looking at on screen?

WANG: It was a fish that -- with the heart beating, it was a fish.

GROSS: OK.

WANG: Yeah.

LAUGHTER

GROSS: One of the main characters in your movie, the character played by Gong Li, is a former prostitute or "hostess," to use the more...

WANG: Right.

GROSS: ... euphemistic word.

WANG: Yeah.

GROSS: And I'm wondering if there are -- were a lot of brothels in Hong Kong before the handover to China -- perhaps still are a lot there -- and if you were aware of that when you were a kid?

WANG: I was very aware of that as a kid. Actually, the area where I grew up in, very close by, there were a lot of so-called "sailor" bars in those days. Hong Kong was an R&R place for, you know, soldiers from Vietnam or all over Asia. And I remember seeing a lot of that, you know, whenever I was, you know, going out at night.

So it's like the world of Suzie Wong -- the bars of Suzie Wong -- they were all over the place. So I was quite aware of it and -- and you know, each time I go back to Hong Kong, I actually am amazed at how much of that is there. You know, there are certain, you know, certain blocks of streets where literally, you know, 80 percent of the buildings are sort of whorehouses, so to speak.

And that one location we filmed in, you know, it's a nightclub called "Beboss" (ph). It's -- it's the size of a football stadium, and when you go in, you actually take an electric car and go to your seat or your booth. And there are 500 or 600 girls that work there every night. It's very -- it's very predominant in Hong Kong.

After the changeover, it still is -- maybe even more so.

GROSS: My guest is director Wayne Wang. His new movie is called Chinese Box. We'll talk more after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

If you're just joining us, my guest is director Wayne Wang, and his new movie is called Chinese Box.

You did some of your shooting for Chinese Box in real situations. In other words, you were using what was actually happening around you and putting your actors into that scene. How did that work for you and what were some of the real scenes that you used as backdrops for your actors?

WANG: There were -- there were, you know, different kinds of scenes that we did like that, but one of the more prominent ones was on the night of June 30th, after the handover, after midnight, it was supposed to be illegal to protest without a permit from the government anymore. And this was a law that was passed, you know, maybe three or four months ago.

And so the -- the local Hong Kong democratic group really wanted to test that law, so they actually, you know, went and protested right after midnight. And Jeremy Irons actually was walking through it and -- and videotaping it on his little digital camera. And so, we were literally right there with the protest and filming it with Jeremy Irons in the foreground.

I mean, luckily again, the police didn't want to do anything about it because they didn't want to, you know, cause a problem on that night. They wanted to keep it basically, you know, controlled. So in that sense, it was -- it was quite interesting, but nothing really dramatic happened.

When -- you know, one thing we saw on the side and the police wouldn't let us film it was that the police had to change their badges and their uniform right at midnight, from an English uniform to actually a more Chinese police uniform.

GROSS: Why wouldn't they let you film it?

WANG: They would get into trouble, I guess, you know, because, yeah, they're not -- I guess they're not allowed to go on film doing something official; doing something that's part of their job in this case.

GROSS: So, when Jeremy Irons was in character making videos of this protest after midnight, did you have contingency plans so that if there was a crackdown and if there was violence, you and he would be able to get out of it?

WANG: Hmmm. Well...

LAUGHTER

... actually I think as -- and again, I mean, Willco Filash (ph) was the director of photography. I mean, he's from Slovenia. And myself and Jeremy -- I think we're all kind of crazy in a way. I think as people who are dedicated or committed to what we're doing, if something happened, I think we would actually go in there and try to film it. I mean, that would be our instinct, rather than try to get out of there.

You know, I think that's -- that's part of where -- where -- you know, why we went there. It's part of -- if something happened, we wanted to be there. So I think we would have gone in there to film it. But -- but if it physically really got dangerous, I think at some point we would -- we would stop.

I -- I guess out of the three of us, I would say I was the most cowardly and I would be the first one to stop. 'Cause I know Willco would go all the way. And I know, you know, Jeremy's pretty -- pretty adventurous and pretty gutsy, and he would go pretty far, too.

GROSS: Wayne Wang is the director and co-writer of the new film Chinese Box. We'll hear more from him later in the show.

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest: Wayne Wang

High: Filmmaker Wayne Wang. With the films "Chan is Missing," "Dim Sum," "Slamdance" and "Eat a Bowl of Tea," to his credit, Wang was the first Chinese-American film director to make an impact in the American film industry. Wang went on to direct "The Joy Luck Club," and the films "Smoke" and "Blue in the Face." His newest film is set in Hong Kong, "Chinese Box" starring Jeremy Irons.

Spec: Movie Industry; Asia; China; Wayne Wang

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1998 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1998 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Wayne Wang

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: APRIL 15, 1998

Time: 12:00

Tran: 041502np.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Actor Insurance

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:25

TERRY GROSS, HOST: Jeremy Irons is going to tell us some of his stories about shooting on location in Hong Kong. First, let's hear his description of the character he plays.

JEREMY IRONS, ACTOR: He's a man who -- who works for a newspaper in Hong Kong. He's a financial journalist -- writes about the money and the deals in Hong Kong. He's lived there for around 15 years and like many people, expatriates who -- who live and work out there, he's -- his marriage has broken up. He went out there with his family and then found himself traveling in Asia, outside Hong Kong, to get to know the financial world there and to write about it.

And his wife eventually gave up and she went back to England because if you're not really in this -- Hong Kong is just about money and about deals and about making a lot of money. And that's why expatriates go there. And I think for a family, it's a pretty arid place to live if you're not part of that.

And so when the film begins, he's not divorced, but he's not living with his family. They're at home in England. And he's a man who is getting to the age when he's beginning to realize that he's lost his way. He's lost -- he's lost his sense of values of what is important in life. That's where we find him at the beginning at the movie.

GROSS: Now, some of the scenes in Hong Kong were set in real places. In other words, there's a scene in which you're talking to journalists and this is the -- a scene in which real journalists are gathered. There's a scene in which you're taking videos of a protest and it's a real protest. It's not a staged protest for the movie.

Did you let everybody around you know: "I'm just an actor here. I'm not really a journalist. I'm an actor playing a journalist." Or did you want them to think you were a journalist? Or maybe you're so famous there was no question about it?

IRONS: I'm afraid they knew I was an actor.

GROSS: Right.

IRONS: And so in some situations, you know, they had to use their imagination to -- but in fact, what is a journalist? A journalist is just a person who -- who is commenting upon things. He's trying to understand situations, then to write about them or -- or to go on radio about them. That's what a journalist is.

What is an actor? He is somebody who is putting himself in a situation and to do that, he asks questions. So there's very little difference. A lot of actors, for instance, write while they're working; I mean, write pieces about their working. So you know, the line is fairly shadowy. So, that wasn't a problem.

GROSS: At the same time that you were shooting "Chinese Box" in Hong Kong, you were in the middle of making a movie in France. And I know that the people in that movie were insistent that you get a lot of insurance for your movie in Hong Kong, in case you were injured and couldn't complete the French film.

You and Wayne Wang decided not to do the insurance 'cause it would have bankrupted the movie. The insurance cost so much that the Chinese Box people couldn't possibly afford it. Was that scary for you? You, taking the risk that just in case something did happen, you would have been in trouble with this other movie.

IRONS: No. I -- I was completely and absolutely confident that nothing would happen. I knew the situation. I think insurers, they have to look at worse, worse, worst scenarios. I was completely confident -- had no doubt at all that I would be able to go do my work and get back in order to complete my contract for "Man in the Iron Mask."

GROSS: It's good that you were able to muster that kind of confidence. I mean, I think a lot of people would find it really hard no matter how confident they think they felt, when someone's saying to them: "no, this might be really bad. No, we have to take out a lot of insurance 'cause you could really be in trouble."

When somebody's like reading you a worst-case scenario, it can be very infectious.

IRONS: Yeah, I've traveled a lot in the world with my career. I think I understand world situations.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

IRONS: I know -- I mean, I got out of Bolivia when there was about to be a revolution. You know, I found a way to get out, even though the airports were completely crammed and there were no flights. I -- I -- I know how to get about. I travel enough. So, I suppose I was completely confident.

GROSS: Jeremy Irons stars in the new movie Chinese Box. We'll talk more with the director and co-writer of the film, Wayne Wang, in the second half of the show.

I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest: Jeremy Irons

High: Oscar winning British actor Jeremy Irons. He stars in two new movies this year: "Chinese Box" and "Man in the Iron Mask." His films include: "The French Lieutenant's Woman," "Brideshead Revisited," "Reversal of Fortune," and "Dead Ringers."

Spec: Movie Industry; Chinese Box; The Man in the Iron Mask

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1998 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1998 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Actor Insurance

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: APRIL 15, 1998

Time: 12:00

Tran: 041503np.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Wayne Wang Part II

Sect: News; International

Time: 12:30

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Back with more of our interview with Wayne Wang, whose films include "Joy Luck Club," "Smoke," "Dim Sum," and "Chan is Missing." He co-wrote and directed the new movie "Chinese Box," which is set in Hong Kong during its transition from British to Chinese rule. Wang lived in Hong Kong until he was 18.

Your parents fled to Hong Kong from China in 1947, after the communist takeover of China. I understand your mother was pregnant with you at the time. Do you think of yourself as having made that journey in utero?

WAYNE WANG, FILM DIRECTOR, "CHINESE BOX": I definitely think of that...

LAUGHTER

... think of it that way. And I think of it as also kind of an unwanted child. I mean, who would plan a baby in the middle of escaping from all of this stuff? So I must have happened, you know, by accident out of this turmoil.

So -- and I feel like there's a part of me that's always really anxious. There's a really, you know, big anxiety part of my personality. And I think it comes from the fact that my mother was carrying me, and actually running and escaping from China, so to speak.

So I think my -- my -- very much of my personality and my psychology's affected by it.

GROSS: How pregnant was she when -- when -- during the actual fleeing part?

WANG: I -- I was born -- I was born literally I think two weeks -- within two weeks after she arrived in Hong Kong. So she was probably, you know, throughout the whole pregnancy, she was going from let's say North of China to Shanghai to South of China somewhere.

GROSS: Wow. What had your father done for a living in China?

WANG: My father was an import-export businessman, but he did a lot of -- lot of business with the U.S. Navy in China. So that's where he actually got into movies. He was always, you know, watching movies where the Navy's were showing -- showing, you know, all these American Hollywood films.

GROSS: Oh, and I know you were named after John Wayne, so I guess they probably showed a lot of John Wayne movies, huh?

WANG: They showed a lot of John Wayne movies. Like, my dad had just seen "Red River" and was really, you know, enamored with John Wayne and everything that he stood for and all that. So...

GROSS: I notice he didn't name you Montgomery after the...

WANG: Yeah. That's true. He almost -- that's another...

LAUGHTER

... I could have been called Montgomery Wang, actually.

GROSS: That's right.

LAUGHTER

WANG: Or MacArthur Wang, 'cause he was also a big fan of MacArthur -- General MacArthur.

GROSS: Yeah, wow. Now did you share your father's enthusiasm for John Wayne? And I wonder what it was like for you, for instance, during the -- the Green Berets era, when John Wayne, instead of signifying like American icon, to people who opposed the war, he signified, you know, the staunch support for an unjust war.

WANG: Yeah, I mean, I -- growing up, I mean my father is basically kind of, you know, anti-communist because, you know, he had to leave because of the communists. And that's why he also fell in love with all these, you know, American imperialistic movies, so to speak. And I was very much influenced by it. I remember my brother and I would see these movies and go back and we would -- I would be, you know, Audie Murphy. He would be John Wayne. We would kill a lot of, you know, Japanese soldiers.

LAUGHTER

GROSS: Well, that's strange.

WANG: Yeah -- not the Chinese, 'cause I guess the Americans were never really at war with the Chinese. The Chinese were always sort of being saved by us, but we were the imperialist Americans. And we were also doing a lot of cowboys and Indians movies and you know, I -- you know, we would play cowboys and kill a lot of Indians.

GROSS: You had mentioned that your father was in the import-export business in China. What did he do when he got to Hong Kong?

WANG: He continued in import and export business.

GROSS: What kind of stuff?

WANG: Well, everything. I mean, in Hong Kong -- I mean, Hong Kong is a place where you have to be real creative. I remember he -- he was buying old ships and tearing them down for -- for iron and metal or something. He was buying islands and mining lead. He was opening up garment factories making jeans.

I mean, I was amazed at all the different kinds of businesses he's been in.

GROSS: Did he make a good living at it?

WANG: He made pretty good living. He also lost -- I mean, he made a lot of money; he lost a lot of money. I mean, you know, I remember in the garment factory, you know, it was -- he -- he just hit it at the wrong time and he lost a lot of money in garments.

GROSS: My guest is director Wayne Wang, and his new movie is called Chinese Box.

Have your films played Hong Kong?

WANG: Some of them have.

GROSS: Which -- what's your reputation in Hong Kong? Are you a popular director there?

WANG: Yes and no. I'm probably...

LAUGHTER

... I'm probably a director who in their minds probably make very small, non-dramatic art films. And perhaps you know, they might think of me as somebody more American than Chinese. 'Cause every time I make a Chinese film, they say I'm not Chinese -- or not Chinese enough.

GROSS: I know you went to Catholic schools in Hong Kong.

WANG: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: Were Catholic schools a mix of British and Chinese culture?

WANG: Yeah, very much so. The one I went to was a little different. The one that I went to was more exclusively Chinese, although the school was a British, you know, Jesuit school. But, they tried to emphasize the Chinese part a little bit more. So, I'm lucky that way.

But most of the private school or Catholic schools or what not are, well not most -- I would say half and half. You know, a lot of them are actually very, very English-oriented.

GROSS: In your movie Chinese Box, there are some examples of the difficulties that, say, a Chinese person and a British person would have in having an intimate relationship with each other -- I mean, that there were social customs that mitigate against that. Did you find that to be true when you were young? That there was just a limit to the kinds of relationships British people and Chinese people could have with each other?

WANG: Yeah, when I want to school -- when I was in high school, actually, some of my friends would go out with English girls. And they inevitably would, you know, end up kind of, you know, problematic. And you know, it was -- it was -- it would be a problem for both sides of the family, not just from the English side.

But generally speaking, I would say the English side was -- was much more racist about it. And I remember specifically, and this is mentioned in the movie I think, where certain big English companies in Hong Kong would have their English employees actually sign contracts saying that they would not have close relationships with the Chinese. So...

GROSS: Who would make them sign that?

WANG: The big companies.

GROSS: Hmm.

WANG: Like the big banks or the big English companies. You know, so generally speaking, I mean, the younger kids probably, you know, for whatever reasons, they're much more on the cutting edge and wanted, you know, deal across cultural -- but the parents were often really against it.

And part of the problem also -- and this is somewhat reflected in the Maggie Chung (ph) character -- is that like myself also, a lot of the Chinese kids wanted to be more Western because, you know, as we talked about, the role models on the screen were all white people. They wanted to be more Western. They wanted to be English. And in a way, there's a lot of denial there.

GROSS: You say that you wanted to be more Western, and you thought of yourself as being comparatively Western when you were growing up in Hong Kong. You went to the United States at the age of 18 to study film. Did you feel much more Chinese when you got to America?

WANG: No. Actually, I was so scared about not fitting in that I -- that I wanted so badly to become more Western and more American. I just did everything I could to fit in. I did everything I could to feel like I could have grown up in America.

GROSS: What did you do?

WANG: And it wasn't -- what did I do? I -- I had an operation on my eyes -- no.

LAUGHTER

I guess I -- you know, I first of all, you know, tried to speak with a California accent. I tried to...

GROSS: Wait. Let me stop you. Was there any like cool slang of the period that you had to work in right away?

LAUGHTER

WANG: Ooh, OK. I don't -- I -- nothing comes to mind right off-hand.

GROSS: What year was this? Maybe I can make some suggestions.

WANG: This was -- this was 1968.

GROSS: Oh, well.

WANG: What was -- what was big in 1968?

GROSS: "Cool," "groovy," "far out" "dude"...

WANG: Yeah, "cool," "groovy," "far out" -- they were all in. Yeah, there were a lot of drugs going on and everything -- cool, groovy was very big. Yeah.

GROSS: And what was it like coming from a Chinese culture to the middle of the so-called "sexual revolution?"

LAUGHTER

WANG: Oh, that's -- that's scary.

LAUGHTER

I had -- you know, I had no idea what was coming. So, I -- I was really -- I was really scared -- really, really, really lost by all of it.

GROSS: But did you have to pretend that you weren't?

WANG: I -- I -- oh yeah, I definitely had to pretend I wasn't. I wasn't dating very much because I was so scared of all that. So, it was a very difficult time for me. I mean, like, you know, I was going through adolescence. I, you know, I was -- I was -- I was a foreign student.

I was Chinese. I spoke English with a British accent. They didn't know what to work -- what to make of me. And, you know, they -- the community -- the first couple of years, I was in Los Altos, which is, you know, I would say 90 percent white. There was maybe one or two black students and one other, you know, Chinese-American in my school.

GROSS: So, you came to America to make movies. When you started studying movies, did you still feel like, OK, this is going to work? Or, did you get discouraged?

WANG: Well, when I first started, I didn't study films because I didn't think that I could even, you know, begin to make films. So, I studied painting. I started with that and then I moved into photography and then at graduate school there was a film department and I started making films.

And at that point, I -- I was really into it and I really felt I could get my hands on equipment. I could get my hands on film and I could actually, you know, make something.

GROSS: Now, I know after you went to college, you moved back to Hong Kong for a while -- worked in Hong Kong television. Then, moved back to the States and did social work here -- working with Asian immigrants.

WANG: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: What made you decide to try social work?

WANG: You know, when I finished college in America, I had become, so to speak, completely American, 'cause I -- I can be quite chameleon that way. And I went back to Hong Kong, and I realized after going back to Hong Kong that I really didn't know my own culture. I was losing my own language. I -- I really had denied my own, you know, upbringing so to speak.

So -- and I couldn't stand Hong Kong at that time. So, I quit everything there and went back to California to San Francisco, and went back into the Chinese community and worked with the Chinese, using -- using my own language. At the same time, I was studying a lot of, you know, Chinese literature again -- for the first time.

And this, I guess, you know, it was also influenced by the Chinese-American movement here, where Chinese-Americans were saying, you know, we're Chinese also and you know, they were studying their Chinese. They were studying, you know, Chinese-American literature. So I was very much, you know, part of that whole movement.

So that's when I really started kind of getting back in touch with my own roots and my own culture and language.

GROSS: My guest is director Wayne Wang. His new movie is called Chinese Box. We'll talk more after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

My guest is Wayne Wang. He directed and co-wrote the new movie Chinese Box, which is set in Hong Kong.

Your first feature film, "Chan is Missing," was an independent film -- very low budget. But it was made before the current vogue for independent movies. Do you think that it was more difficult for you to make a movie and to get financing than it would have been if you were doing it today?

WANG: Yeah, I think it was -- in those days, it was unheard of, almost. So I tried to get money to make a movie, you know, every which way and I was turned down. Finally, actually, the National Endowment for the Arts gave me a grant because I was a minority, actually. And you know, I had $25,000 as a grant, but I was crazy enough to say: "well, you know, if I do it carefully, maybe I can make a feature." So I just, you know, did it.

I think it's -- more than anything it was out of ignorance that I was able to do that.

GROSS: Your movie career has kind of alternated between Chinese-themed movies like Chan is Missing, Dim Sum, Eat a Bowl of Tea, The Joy Luck Club -- and movies that, you know, aren't about Asian people or Chinese life -- movies like "Slamdance" and "Smoke."

And it seems to me that's probably pretty conscious on your part, to do both and to make sure that you do both.

WANG: Yeah. Well, I think because of my own experience, you know, being kind of more than one culture -- more than one identity. I think, you know, I -- I consciously want to make films that's not just about the Chinese, you know. There's a very -- there's a part of me that -- that loves, let's say, New York City and Brooklyn. That's why I made a film about it.

You know, and working with Reuben Blades (ph) -- I was so interested about him talking about, you know, Panama and also the Latin community here. I'd love to make a movie, you know, with him and some of the music friends that he has, you know, for example.

So I mean, I'm always trying to -- look at the world from all these different cultural perspectives. You know, I think it's really interesting. I mean, the world is getting so much smaller and so global these days -- you know, with e-mail, with how much people travel and how much people have migrated to different countries.

I think it's -- it's really important for the next millennium -- for the future.

GROSS: You directed Harvey Keitel in Smoke. He's such a great actor and he -- was such a fine performance in that movie. Did you learn anything from working with him?

WANG: I learned that, you know, that actors need secrets; that actors, you know, don't want to be told everything; that in a way, they -- they want to have their own secrets. They want you to give them secrets that other actors don't know.

They want, maybe, to do things -- to let things happen by having you tell other actors what -- what you want, you know, to happen and not let them know. It's all about secrets. That's the one thing I learned from Harvey that I find really valuable and really precious.

GROSS: How -- how did you learn that from him?

WANG: Well, 'cause when we finished filming Smoke, we did "Blue in the Face." And Blue in the Face was more improvised. And one of the, you know, premise that -- that -- that -- that improvisations are built on is that each actor knows something that the other actor doesn't. And that's what makes for drama and what makes for these improvisations to work, you know, better.

GROSS: So was there something that he knew that other didn't? Or that someone else knew about him that he didn't know they knew that led to this revelation?

WANG: Exactly.

LAUGHTER

GROSS: Would you say what it is or...

WANG: They could get a -- well -- well, to be more explicit, a more dramatic example is that you know there is a scene in Blue in the Face where, you know, all these guys are talking about the sister of this woman who comes in to buy cigarettes. And -- and you know that she's going to get mad, but nobody knew that actually, you know, she was going to just walk up to one of the more vocal guys and slap him as hard as she could.

And he -- and everyone was surprised by that. And you know, and that's something -- I mean, that's a very, very dramatic example. It could be more subtle, but that's -- that's something that a character does that she keeps a secret; that she will not let the actors know until she does it.

And then when she does it, then, you know, whatever happens becomes real. I mean, it was -- I was very interested to see what would this guy do? This is a macho guy who's very physical; who's very vocal. So, what is he going to do?

It turns out that this guy sort of was in complete silence, 'cause he could not believe that she came up and slapped him in the face so hard.

GROSS: So, Harvey Keitel was just stunned...

WANG: And Harvey Keitel was stunned and started smiling and laughing.

GROSS: And you kept that in the movie.

WANG: And we kept it in the movie, yeah. You know, that's -- that's the kind of stuff that really creates tension and drama in a scene, so...

GROSS: Did you keep any secrets from Jeremy Irons?

WANG: I tried to, you know. I tried to, but Jeremy is really good. He -- you know, in a quiet way, he digs everything out of you.

LAUGHTER

But I still did. I think there were -- I think, again, I mean, I -- I tried to keep secrets from Jeremy, for example, often -- you with, again, with Gong Li (ph) and Reuben Blades a lot. You know, I would have Reuben say certain things to Jeremy without letting Jeremy know. Or for Gong Li to do something that Jeremy doesn't know.

For example, there's a scene where Jeremy is really upset with Gong Li and wants -- doesn't want her to be around anymore. He was verbally abusive of Gong Li. And I told Gong Li: "well, the more abusive he gets, you know, why don't you go over and very, very tenderly touch his face." So, that was a secret that I kept from Jeremy. And then, Jeremy reacted even more violently to that.

GROSS: And did you expect that?

WANG: Because he didn't want to be -- I did not expect that. I mean...

GROSS: Did you like it?

WANG: I liked it. Actually, it -- it was very, you know, it was a very interesting reaction because Jeremy's character was always -- you know, Jeremy was always telling me that one of the things he wanted to do with his character was that he didn't want to look into his friend's eyes and see that he's dying. He didn't want people to pity him.

So for that moment, for Gong Li to touch him, to feel pity for him, he was really upset. So, he really wanted to go against it. So, he kind of came at her even more.

That's what, you know, creates more tension. And that's a really interesting way to work.

GROSS: You and Francis Ford Coppola have a new production company called "Chrome Dragon."

WANG: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: What's the mission of the company?

WANG: Well actually, Francis Ford Coppola and myself over the years have, you know, loved all these, you know, Kung Fu movies from Hong Kong. And we've always talked about, you know, trying to encourage young directors from there -- not just Hong Kong, maybe even all over Asia -- to make some of them. But also, you know, help them, you know, make them with a little more story and character.

I mean, you know, Francis being sort of the Godfather of Godfather films, I mean, I think the power of what he did was that they are not only action films, but also great story and character. So that's our intention -- is to instead of like all these directors from Hong Kong coming to Hollywood, we want to just bring some of Hollywood to Asia and encourage them to keep their unique qualities, the styles -- and make films their way. You know, except, you know, give them the encouragement of more story and character.

GROSS: Well Wayne Wang, I want to thank you very much for talking with us.

WANG: OK. Thank you.

GROSS: Wayne Wang directed and co-wrote the new film Chinese Box. It opens Friday in New York and Los Angeles. It opens in other cities next weekend. Chinese Box will close the San Francisco Film Festival this Friday.

Coming up, Lloyd Schwartz tells us the story of how he rescued a poem by Elizabeth Bishop.

This is FRESH AIR.

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest: Wayne Wang

High: Filmmaker Wayne Wang. With the films "Chan is Missing," "Dim Sum," "Slamdance" and "Eat a Bowl of Tea," to his credit, Wang was the first Chinese-American film director to make an impact in the American film industry. Wang went on to direct "The Joy Luck Club," and the films "Smoke" and "Blue in the Face." His newest film is set in Hong Kong, "Chinese Box" starring Jeremy Irons.

Spec: Movie Industry; Asia; China; Wayne Wang

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1998 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1998 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Wayne Wang Part II

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: APRIL 15, 1998

Time: 12:00

Tran: 041501np.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Saving Breakfast Song

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:55

TERRY GROSS, HOST: Music critic Lloyd Schwartz is also a poet, and has written extensively about the American poet Elizabeth Bishop, who died in 1979. For National Poetry Month, Lloyd tells us the story of how he got to know her and how he happens to have the only known copy of one of her poems.

LLOYD SCHWARTZ, FRESH AIR COMMENTATOR: I first got to know Elizabeth Bishop when she moved to Cambridge in the early 1970s, after living in Brazil for nearly 20 years. I admired her small output of poems and I was thrilled to meet her. But she was very shy about discussing her work, and I didn't think I had anything else to talk to her about.

Eventually, the barriers began to come down. I was floored by the new poems she was writing and it got to be easier to tell her that. We got to be friends under circumstances unfortunate for her, but lucky for me. She'd had an accident during Christmas vacation. Her friends were away, but she remembered my complaining that I'd be stuck in town.

For a week, I spent every day with her at the hospital, stopping off at her apartment to pick up her mail and any other odds and ends she requested. Suddenly, we found it easier to talk about movies and records -- she loved Mozart and Billie Holliday -- and some more personal things.

I even got to see a new poem she was working on, called "Breakfast Song." It was a short love poem, but more than that, it was a poem about facing her own mortality, or her reluctance to face her mortality. I thought it was amazing, and courageously open about her feelings of love and fear of death.

I wanted to read it over and over. And when she was out of the room for some medical procedure, I copied the poem without telling her. I think maybe I was also worried that it was a poem she might decide was too personal to publish; that she might even destroy it. She never published it during her lifetime.

After she died, I hoped that someone would find it among her papers. But although numerous unfinished or unpublished poems have come to light since her death, Breakfast Song was not one of them. A couple of years ago, when I heard that her publishers Farrar Strauss and Giroux were planning to publish a volume of her uncollected poems, I thought it was time to confess my guilty secret.

I still feel slightly queasy about what I had done, but I couldn't bear not being able to read this poem.

Breakfast Song.

My love

My saving grace

Your eyes are awfully blue

I kiss your funny face

Your coffee-flavored mouth

Last night, I slept with you

Today, I love you so

How can I bear to go

As soon I must, I know

To bed with ugly death

In that cold, filthy place

To sleep there without you

Without the easy breath

And night-long, limb-long warmth

I've grown accustomed to

Nobody wants to die

Tell me it is a lie

But no, I know it's true

It's just the common case

There's nothing one can do

My love

My saving grace

Your eyes are awfully blue

Early and instant blue

GROSS: Lloyd Schwartz is editor of "Elizabeth Bishop and Her Art." He reads Breakfast Song, the poem we just heard, on a new CD called "One Side of the River," featuring poets from Cambridge and Somerville, Massachusetts.

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

Dateline: Lloyd Schwartz, Boston; Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest:

High: Classical music critic Lloyd Schwartz on poet Elizabeth Bishop and how he saved a poem of hers from obscurity. It's called "Breakfast Song." Lloyd is the editor of "Elizabeth Bishop and Her Art." The poem "Breakfast Song" is not in that collection or any other printed collection. It can, however, be found on the CD: "One Side of the River" featuring 35 Massachusetts poets.

Spec: Arts; Music Industry; Poetry; Elizabeth Bishop; Breakfast Song

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1998 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1998 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Saving Breakfast Song

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.