Other segments from the episode on February 10, 2017

Transcript

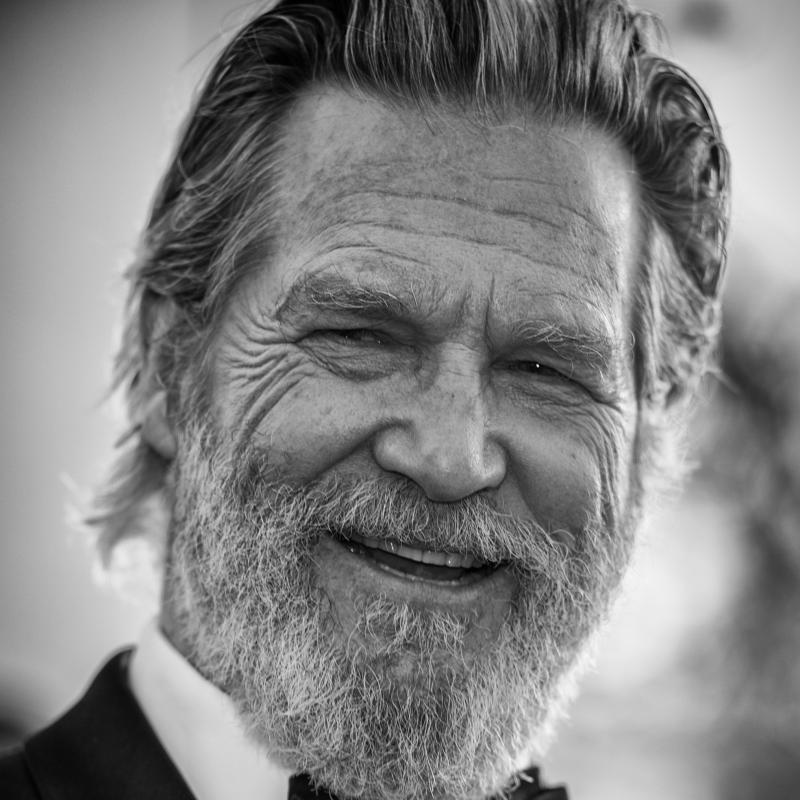

DAVE DAVIES, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies, in for Terry Gross. Today, we continue our series of interviews with Oscar contenders with Jeff Bridges, who's earned a nomination for best supporting actor for his performance in the modern Western "Hell Or High Water." Bridges and his brother, Beau, grew up in show business. They sometimes appeared in the TV series "Sea Hunt," which starred their father, Lloyd Bridges.

Jeff Bridges got his first Oscar nomination at the age of 22 for his role in the 1971 film "The Last Picture Show." He's earned five more since and finally won the best actor Oscar for the 2010 film "Crazy Heart." Among his other films are "Heaven's Gate," "Starman," "Jagged Edge," "The Fabulous Baker Boys," "True Grit," and "The Big Lebowski."

I spoke to Bridges last month. And we began with "Hell or High Water." It stars Ben Foster and Chris Pine as two brothers who are robbing small-town branches of a bank in West Texas. Bridges plays an aging Texas Ranger investigating the crimes. In this scene, he's speaking with a witness, then other investigators, after one of the robberies.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "HELL OR HIGH WATER")

JEFF BRIDGES: (As Marcus Hamilton) I know their faces was covered, but could you tell their race - black, white?

DALE DICKEY: (As Elsie) Their skin or their souls?

BRIDGES: (As Marcus Hamilton) Let's leave their souls out of this for now.

DICKEY: (As Elsie) White. From around here somewhere is my guess, you know, from their voices.

GIL BIRMINGHAM: (As Alberto Parker) Young County says the same deal with the branch in Olney.

BRIDGES: (As Marcus Hamilton) Excuse me. Do they have video?

BIRMINGHAM: (As Alberto Parker) Same deal all the way around.

BRIDGES: (As Marcus Hamilton) Doesn't Wal-Mart sell all sorts of electronic equipment? My word, get your hands off that. Now, these boys - they aren't done yet, I'll tell you that.

BIRMINGHAM: (As Alberto Parker) How come?

BRIDGES: (As Marcus Hamilton) Well, they're patient, just sticking to the drawers, not taking the hundreds. That's the bank's money. We can trace that. They're trying to raise a certain amount. That's my guess. It's going to take a few banks to get there.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

DAVIES: Well, Jeff Bridges, welcome to FRESH AIR.

BRIDGES: Thank you for having me.

DAVIES: Tell me about this character Marcus, this Texas Ranger, and how you got him.

BRIDGES: Well, this fellow, this Texas Ranger I'm playing, Marcus, in this movie - he's going through the pain of retirement, something that actors, you know - we're - we can act on our deathbed.

(LAUGHTER)

BRIDGES: You know, so it's something that I had to do a little research about that and find out what that was all about. And, also, we were fortunate to have on the set for many days Joaquin Jackson, who was a very notable Texas Ranger. You know, he's written several books. He's - you know, he was just, you know - just so, so wonderful to have him on set not only to tell us, you know, how - you know, what our uniform should look like, how Texas Rangers behave and all that, but just to have him in the room and pick up the, you know - his vibes. And to have his support and his blessing was really important.

DAVIES: One of the fun things about the film is your relationship with your partner, Alberto, who is played by Gil Birmingham. This character is half Mexican-American, half Comanche. You want to just talk a little bit about that? It's a friendship with an edge, isn't it?

BRIDGES: Yeah. They're dear friends (laughter), but Marcus teases him terribly throughout the film with, you know, racial slurs and so forth. One of the first things I do when I'm preparing for a part is I kind of look inside myself and see what - are there any aspects of myself that might be handy in portraying this character? And my grandfather, Fred Simpson, was a terrible teaser. And my brother, Beau - he inherited that (laughter) teasing gene - used to really tease me, you know, in an awful way and, you know, get me crying and stuff. And my mom would say, oh, that's just because he loves you so much, you know?

DAVIES: (Laughter) Yeah.

BRIDGES: And I, you know - I realized that that was probably true - you know, that it was an expression of intimacy. You know, I know exactly what buttons to push to get a, you know - a rise out of you. That's how much I love you or that's how well I know you. So that was something I could kind of tap into playing the role.

DAVIES: Yeah. You know, a lot of us tease our friends about them being clumsy or bad drivers or whatever. It's a little touchier when you're talking about their ethnicity. And...

BRIDGES: Yeah, well - yeah, yeah. Yeah, I agree with that. I think a lot of that has to do with how you were raised, what part of the country you were brought up in. Another touchstone for me in this film and in other times I'm playing Texans - I play quite a few Texans or, you know, Westerns - is a fellow that I met on "The Last Picture Show" called - his name is Loyd Catlett. And he had a small part in "Picture Show." And he was also hired to teach us California kids how to be Texas kids.

And we became friends and now - turns out we've done over 70 films together. He's my stand-in for all these movies. He's kind of like a constant thread through the movies. And, you know, when we first met, he like - the friends he grew up around, you know, would use racial slurs and stuff, not - he was funny - not in a necessarily mean way. It was just the - those were the terms. Those were the words that were used.

And hanging out with the California kids, you know, he kind of - we said, oh, don't say that, Loyd, you know? And he was, you know, full of love and - but that's just how he was raised.

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR, and we're speaking with actor Jeff Bridges. He stars with Chris Pine and Ben Foster in the film "Hell Or High Water." I want to play a scene here of - we'll talk about it afterwards - a scene of a kid and his dad on a scuba diving boat.

(LAUGHTER)

DAVIES: And the kid's gotten into some mischief on a dive. Let's listen.

BRIDGES: Oh, my God.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "SEA HUNT")

LLOYD BRIDGES: (As Mike Nelson) Kelly, if you've got something to say now, say it.

BRIDGES: (As Kelly Bailey) They didn't get all the dynamite out. There's still some there.

L. BRIDGES: (As Mike Nelson) Where?

BRIDGES: (As Kelly Bailey) When we were diving, there was a buoy with a sign that said A-zone on it.

L. BRIDGES: (As Mike Nelson) Why didn't you say this before?

BRIDGES: (As Kelly Bailey) I was afraid. I promised.

L. BRIDGES: (As Mike Nelson) Promised who?

BRIDGES: (As Kelly Bailey) Joey.

L. BRIDGES: (As Mike Nelson) Pete, head for that A-zone buoy.

BRIDGES: (Laughter).

DAVIES: A little taste of our guest, Jeff Bridges, and what we were you 8 or 9 then?

BRIDGES: Yeah. That's wild.

DAVIES: Acting with your dad, Lloyd Bridges, in the series "Sea Hunt," which I remember watching. Your dad played Mike Nelson, this diver who went around rescuing people and besting criminals and all. You learned a lot from your dad. I read that you'd sit on the bed and he would talk to you about - teaching you the basics of acting.

BRIDGES: Oh, yeah, yeah. He - you know, especially with "Sea Hunt," he'd get me on the bed there, you know, and teach me how to - you know, make it feel like it's happening for the first time and not to just, you know, wait for him to stop speaking and then I'd do my line. He says you got to listen to what the other guy's say and let that have some effect on what you're going to say. And now go out of the room. Now come back in and do a completely different version of - you know, all kinds of stuff like that.

Later on, I got to work with him as an adult. We did a movie called "Tucker" together and also "Blown Away." And that was a wonderful experience. And I learned probably the most important thing I ever learned from him on those movies, And that was the way he generally approached the work, which was with such joy. He enjoyed what he was doing so much. And he was, you know - he really wanted all his kids to go into acting because he loved it so much.

DAVIES: Yeah. It's interesting, you know, 'cause some kids whose parents push them into show business, you know, it doesn't always make for the happiest relationships or happiest lives.

BRIDGES: Yeah.

DAVIES: And I'm picturing you on that bed thinking, oh, dad, come on. I want to go out, play ball...

(LAUGHTER)

DAVIES: ...You know? But you liked it.

BRIDGES: Well, yeah.

DAVIES: It was fun?

BRIDGES: Well, sort of. But, you know, like most kids that age, you don't want to do what your parents want you to do. You know, you get your own ideas. And I certainly had a pile of them. You know, I wanted to, you know, get into music and, you know, painting. And I had a lot of different interests.

And my father said, oh, Jeff, don't be ridiculous. That's the wonderful thing about acting is you get to incorporate all of your interests in your parts. And you'll get to, you know, do some music and all of that. It'll facilitate that stuff. And he was right. I'm glad I listened to him (laughter).

DAVIES: Yeah. You know, I think of all these actors we've interviewed who spent 15 years waiting tables in New York and doing plays and commercials hoping to break into it. And you had a real entree, and you weren't so sure about it. Was there a point - was there a turning point in which you said, yeah, this is it?

BRIDGES: Yeah. There was. And also, you know, the whole nepotism thing - that's, you know, something a kid wants to avoid, you know, getting a job just because of who his dad is. But that was kind of the case of my part. And the turning point was late in my career. I had done quite a few films. And I just finished a movie called "The Last American Hero." And right after I finished that movie, I got a call from my agent saying that John Frankenheimer wanted to cast me in "The Iceman Cometh" along with Fredric March and Lee Marvin and Robert Ryan, who were going to be in it. And I said, oh, well, thanks a lot, Jack, but I'm bushed.

DAVIES: (Laughter).

BRIDGES: I tell him I'll pass - thank him, though. And about a minute after I hung up, Lamont Johnson, the director I just worked with, called me up. And he said, I understand that you turned down "The Iceman Cometh." And I said, yeah. I'm bushed, Lamont, you know? And he says, bushed? You're an ass. And he hung up the phone (laughter). And I thought, oh, gee. Well, maybe I'll try a little experiment on myself.

Maybe I'll just do this movie. And maybe it'll be the final nail in the acting coffin for me. You know, I'll say, oh, this was a terrible experience. I'll do something else. And it turned to be quite a unique experience for many reasons but one being that we had eight weeks rehearsal. You know, usually if you're lucky, you've got a couple of weeks. And we shot the movie for two weeks. And I got to hang out with these old masters a lot, you know? And they were just as anxious as I was (laughter) about getting it right, you know, doing the material justice. And watching these guys dealing with their flop sweat and their anxiety and all that was kind of heartening for me. And I learned that that's not something that goes away.

I remember Robert Ryan - doing a scene with him. And, you know, we started to do the scene, and then they said, oh, no, we've got to stop the camera, fix a light or something. And he takes his hands off the table. And there are big puddles of sweat there on the table. And I say, Bob, guy, after all these years, you're nervous? What is that? And he said, oh, I'd really be scared if I wasn't scared. You know, he just had to, you know - incorporated that anxiety into his work. And, you know, parts of it is a good thing. It's what makes you learn your lines and, you know, get it right, you know?

DAVIES: You know, you come from a family of actors. And your brother Beau, of course, also had a career. You guys appeared in some films together - "Fabulous Baker Boys." What's it been like to have a brother who's a successful actor, too?

BRIDGES: Yeah. Well, right along with my dad, my brother Beau was my teacher. He taught me so much about acting. One of the challenges for, you know, actors starting out is, where do you perform? And Beau - and this is - I must've been, you know, 16 - 15, 16 years old. He came up with this great idea of renting a flatbed truck, and we would pull into a supermarket. And our father, Lloyd, taught us how to stage fight, you know, fake fight. And we would stage this fake fight. And a crowd would, you know, gather around the parking lot, watching these two guys go at each other. And then we'd say - you know, break our fight up and say, no, we're putting on a show. And we'd jump on the back of the flatbed truck and perform our scenes that we'd worked on until the police came.

DAVIES: (Laughter).

BRIDGES: And then they would be very upset because we would try to do an improv with them and try to bring them into our show.

(LAUGHTER)

BRIDGES: And they were - really started to get serious. We'd say, no, we're leaving, and we'd get back into the truck, and we'd go to the next supermarket. And we played the supermarket circuit that way. But Beau, you know, helped me with, you know, all - you know, getting an agent, you know, all of that. And then working with him in "Fabulous Baker Boys" - oh, that was just a dream come true, you know? We would...

DAVIES: And you guys had a fight in that, didn't you?

BRIDGES: Oh, we had a terrible fight (laughter). Yeah, we had a fight. We were so thrilled from this story that I just told you that we were going to have this fight. And Steve Kloves - it was his first movie - director. And we asked Steve if we could gaffe this fight. And he said, sure. Yeah.

So we had it all arranged. And - but we forgot a very important element, which was a safe word, a word that would say, no, you're really hurting me. Stop doing what you're doing. And so at the climax of the fight, my character grabs my brother's hand. He's a piano player. And I proceed to bend his fingers back. And Beau's saying (shouting), ah, ah, stop. You're hurting me.

And I'm thinking in my mind, yeah, act your ass off, man.

(LAUGHTER)

BRIDGES: And I sent him to the hospital. I had hurt his fingers terribly. So you must have a safe word, people.

DAVIES: We have to talk about "The Big Lebowski," the film that you made with the Coen brothers in 1998. And let's start with a classic scene from the film. You play this - I guess what we'd call an aging stoner, Jeff Lebowski, but a guy who's known to all of his friends as The Dude. And we'll listen to a scene early in the film. And what's happened is that a couple of tough guys broke into your apartment, looking for money they said you owed. It turned out they were confusing you with another guy named Jeff Lebowski, who's a rich guy. But before these tough guys left, one of them peed on the rug in your living room. And in the scene we're going to hear, you've come to see the rich Lebowski to ask him to cover the damage.

BRIDGES: (Laughter).

DAVIES: And Mr. Lebowski, who is played by David Huddleston, speaks first. Let's listen.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "THE BIG LEBOWSKI")

DAVID HUDDLESTON: (As Jeff Lebowski) What can I do for you, sir?

BRIDGES: (As The Dude) Ah, well, sir, it's this rug I have. It really tied the room together.

HUDDLESTON: (As Jeff Lebowski) You told Brandt on the phone. He told me. Where do I fit in?

BRIDGES: (As The Dude) Well, they were looking for you, these two guys. You know, they...

HUDDLESTON: (As Jeff Lebowski) I'll say it again. You told Brandt on the phone. He told me. I know what happened - yes, yes?

BRIDGES: (As The Dude) Oh, so you know that they were trying to [expletive] on your rug?

HUDDLESTON: (As Jeff Lebowski) Did I urinate on your rug?

BRIDGES: (As The Dude) You mean did you personally come and [expletive] on my rug?

HUDDLESTON: (As Jeff Lebowski) Hello. Do you speak English, sir? Parlez-usted ingles (ph)? I'll ask you again. Did I urinate on your rug?

BRIDGES: (As The Dude) No. Like I said, Woo [expletive] on my rug.

HUDDLESTON: (As Jeff Lebowski) I just want to understand this, sir. Every time a rug is micturated upon in this fair city, I have to compensate the person?

BRIDGES: (As The Dude) Come on. Man, I'm not trying to scam anybody here. You know, I'm just...

HUDDLESTON: (As Jeff Lebowski) You were just looking for a handout like every other - are you employed, Mr. Lebowski?

BRIDGES: (As The Dude) Wait. Let me explain something to you. I am not Mr. Lebowski. You're Mr. Lebowski. I'm The Dude. So that's what you call me, you know, that or His Dudeness or Duder (ph) or, you know, El Duderino (ph) if you're not into the whole brevity thing.

HUDDLESTON: (As Jeff Lebowski) Are you employed, sir?

BRIDGES: (As The Dude) Employed (laughter)?

HUDDLESTON: (As Jeff Lebowski) You don't go out looking for a job dressed like that, do you, on a weekday?

BRIDGES: (As The Dude) Is this a - what day is this?

HUDDLESTON: (As Jeff Lebowski) Well, I do work, sir. So if you don't mind...

BRIDGES: (As The Dude) No. I do mind. The Dude minds. This will not stand. You know, this aggression will not stand, man.

DAVIES: It's still funny.

(LAUGHTER)

DAVIES: And that's our guest, Jeff Bridges, in "The Big Lebowski." How did you get The Dude?

BRIDGES: You know, when I first heard about "The Big Lebowski," it was maybe a year or two before the film. And Joel and Ethan - I saw them somewhere. And they said, hey, we're writing something for you. I said, oh, wonderful 'cause I was...

DAVIES: That's the Coen brothers, right? Yeah.

BRIDGES: Yeah, the Coen brothers - 'cause I was, you know, a big fan of "Blood Simple." It's one of their earlier stuff. And then I got the script, and, you know, I had no memory of any role that I'd ever played like that. It felt like they had, you know, gone to some of my high school parties or - you know, I don't know where...

DAVIES: (Laughter).

BRIDGES: ...They got - you know, why they were writing it specifically for me. But I guess they were on to something 'cause it did kind of, you know, fit some of my - you know, my MO and my - you know, my characteristics, my hair, my look, you know, that sort of thing.

DAVIES: I remembered when we first see you in "The Big Lebowski," I think you're coming down a supermarket aisle, looking for milk for your White Russians.

BRIDGES: (Laughter).

DAVIES: And you're wearing these jelly shoes, some shorts that might even be boxer underwear - they're just barely shorts - and a T-shirt, sunglasses and a bathrobe. It - that kind of just tells the story of this guy almost.

BRIDGES: Yeah, that's right. Those guys - those brothers, the Coen brothers, they really know how to make movies. It's just like falling off a log or it appears to be just falling off a log for them, you know? You don't see the effort in their stuff. But that script is so well-written, and the characters are all so well-defined. It's just a joy to watch.

I still - you know, I'm one of those guys - you know, a movie of mine comes on the tube - on the TV - I'll, you know, watch a scene and then turn the channel. But when "Lebowski" comes on, I - you know, I say, well, I've got to just - I'll just wait until Maude comes, you know, flying down from the ceiling nude, you know, splatters paint all over The Dude. And then I'll say, well, no. I'll just stick to, you know, see Turturro lick the ball, you know? And I get sucked in, you know? And I end up watching the whole thing.

DAVIES: Yeah - one of those movies that never gets old. The film, of course, has this huge following. There are screenings where people show up and in character.

BRIDGES: Yeah.

DAVIES: Do you ever go to these things? Do you welcome this?

BRIDGES: I went to one - I had my Beatle moment at one. You know, I have a band, The Abiders. We once played a "Lebowski" Fest. And you know, I came out - The Dude. (Imitating crowd cheering), you know?

DAVIES: (Laughter).

BRIDGES: And you look out there. And you're playing to a sea of Dudes. They're all dressed up like The Dudes or bowling pins or Maude. You know, they all have the different characters.

DAVIES: Jeff Bridges has earned an Oscar nomination for best supporting actor for his performance in the modern Western "Hell Or High Water."

Well, we have to talk about "Crazy Heart," the 2010 film based on a novel by Thomas Cobb, directed by Scott Cooper. This is the story of an aging musician. You play this musician named Bad Blake, country singer and songwriter who was once on the top whose career is now on the skids mostly due to his very serious drinking problem.

And I wanted to play a scene. Here, you're speaking to a younger country singer, Bobby Sweet, who's played by Colin Farrell. This is a singer who - your character helped start his career, but now you're struggling, and he's on top. And you're in the position of looking for help from him - you know, an album or a concert tour or something.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "CRAZY HEART")

BRIDGES: (As Bad Blake) Hey, how come we're not doing another album? Why won't you do it?

COLIN FARRELL: (As Tommy Sweet) Hold up now. I never said I wouldn't. DMZ just doesn't think it's the right thing to do. That's all.

BRIDGES: (As Bad Blake) I think it is.

FARRELL: (As Tommy Sweet) And you may be right. They want a couple more solos first. Then we do a duet. You got first shot. I already told them.

BRIDGES: (As Bad Blake) I need money now. I'm 57 years old - career's going nowhere. I need something to get it jumpstarted. They won't give me a damn solo album. I need this, damn it. I really do.

FARRELL: (As Tommy Sweet) I swear, Bad, I can't get them to budge on this one. But there is a way you can make some money if you want to.

BRIDGES: (As Bad Blake) Enlighten me.

FARRELL: (As Tommy Sweet) Songs - I ain't got no new material. Everything I'm hearing is straight crap. You write me five new songs - I'll give you backend. I ship 2 million albums every time I release one.

BRIDGES: (As Bad Blake) I haven't written a new song in three years - too many damn songs.

FARRELL: (As Tommy Sweet) You write some of the best material out there, Bad. I want some.

BRIDGES: (As Bad Blake) Wrote, wrote - not write.

DAVIES: And that's our guest, Jeff Bridges, with Colin Farrell in the film "Crazy Heart." You won a best actor Oscar for this. Do you remember how you got this guy, Bad Blake?

BRIDGES: Yeah. Well, Scott Cooper, the director - one of Scott's first bits of directions is that Bad Blake would have been the fifth Highwayman, you know that great group with, you know, Willie Nelson and Kris and Waylon Jennings and Johnny Cash, you know? That was a big help.

DAVIES: You managed to look just terrible, I mean, physically, a guy whose body is ravaged by, you know, all that drinking and too many cigarettes and a terrible diet. And I'm just wondering if there are things that you did to get there. I don't know how you pulled off that.

BRIDGES: Yeah, well, you take off the governor. You know, you let everything just kind of - do what you want. You know, you don't shy away from your Haagen-Dazs. You know, you drink when you feel like it - you know, that kind of thing. And then, of course, makeup helps a lot, you know? You know, putting a little fine, you know, busted blood vessels in your nose and stuff - you know, subtle stuff. But in the morning, you come up to - you get in there in the makeup trailer, and you put on some country tunes. And you start to get your costume on. And when you walk out your dressing room door, there's the guy.

DAVIES: You do all the musical performances in this. And I know you're a musician. So this is not - there was no lip-syncing here. And I want to catch a little bit of one of these performances - this is very early in the film - when your character, Bad Blake, is now reduced, you know, to driving from town to town, playing small gigs with local bands as backups - you know, that you kind of just improvise it and work together. And in this scene we're going to hear, you're up on stage in a bowling alley. And one of the local musicians introduces you. Let's just listen to a bit of this.

(SOUNDBITE OF FILM, "CRAZY HEART")

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: (As character, playing guitar).

RYAN BINGHAM: (As Tony) Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome to Spare Room the wrangler of love, Mr. Bad Blake.

(APPLAUSE)

BRIDGES: (As Bad Blake) Go to C - now F.

(Singing) I used to be somebody, but now I am somebody else. I used to be somebody. Now I am somebody else. Who I might be tomorrow is anybody's guess. I was cleared of all the charges with money, women and my health. I was cleared of all the charges with money, women and my health. But now that I'm a brand-new man, you belong to someone else.

DAVIES: And that is our guest, Jeff Bridges...

BRIDGES: Yeah.

DAVIES: ...In the film "Crazy Heart." That song "Somebody Else" - written by the late Stephen Bruton and T Bone Burnett. You mentioned that you get anxious still with roles. Have you developed techniques over the years on how to deal with that anxiety?

BRIDGES: Well, I meditate. You know, I do that. That helps. You know, that line from "Lebowski" - that's just your opinion, man. You know, you can say that to yourself, too, because, you know, we all have these little voices in our head saying, you know, who do you think you are? You think you're going to pull this thing off? You know, my wife, you know - she often gives me the phrase that my mother used to give me when I would go off to do a job as a teenager. My mom used to say, now remember. Have fun and don't take it too seriously. Oh, thank you. So now I get my wife to say that to me, and that kind of calms me down.

DAVIES: How did your father feel about your career?

BRIDGES: Oh, man, he was so, so proud when I won the Academy Award. I wished he would - and he and my mom could've been there because they would've really loved that moment. But, oh, he just, you know, was very proud of both his guys, both his boys.

DAVIES: Well, Jeff Bridges, it's been fun. Thanks so much for spending some time with us.

BRIDGES: Great hanging with you. Thanks for having me.

DAVIES: Jeff Bridges is up for a best supporting actor Academy Award for his role in the modern Western "High Or Hell Water." The ceremony is February 28.

DAVE DAVIES, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. Fifty years ago this week on February 5, 1967, CBS premiered a comedy variety series "The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour." It starred two young folk song satirists, Tom and Dick Smothers, and very quickly became a focal point on television for the younger generation of the '60s. The Smothers Brothers and their show's writers and performers delivered a hit show in the late '60s while criticizing the war in Vietnam, celebrating rock 'n' roll and recreational drug use and satirizing politics and politicians, including two presidents, Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon.

Along the way, they mixed entertainment and advocacy in a way that was rare to primetime TV then. Our TV critic David Bianculli says some of the messages and lessons of "The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour" seem newly relevant today. He brings us this appreciation.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "THE SMOTHERS BROTHERS COMEDY HOUR")

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: Now, we don't want to offend anybody out there, but if you get offended, that's the way the cookie crumbles.

(LAUGHTER)

DAVID BIANCULLI, BYLINE: Tom and Dick Smothers came to CBS in 1967 not really intending to lead or support a revolution. They just got caught up in it and happened to have a network program with some 30 million viewers as they became politicized and began to reflect it. "Comedy Hour" got its message out at first slowly and sometimes sneakily. A lot of it came through the music and the hot new acts booked to perform.

Over the run of the show, it was like a series of anthems from the counterculture - from Buffalo Springfield singing "For What It's Worth" to The Beatles singing "Revolution," with the American TV debut of The Who and the West Coast cast of "Hair" and Dion singing a song about assassinated heroes in between.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "THE SMOTHERS BROTHERS COMEDY HOUR" MONTAGE)

BUFFALO SPRINGFIELD: (Singing) There's battle lines being drawn. Nobody's right if everybody's wrong. Young people speaking their minds getting so much resistance from behind. We got stopped. Children, what's that sound? Everybody look what's going down.

THE WHO: (Singing) People try to put us down. Talking about my generation. Just because we get around. Talking about my generation. Things they do look awful cold. Talking about my generation. I hope I die before I get old. Talking about my generation.

THE BEATLES: (Singing) You say you want a revolution. Well, you know, we'd all love to change the world. You tell me that it's evolution. Well, you know, we'd all love to change the world.

BIANCULLI: The Beatles didn't appear live to sing "Hey Jude" and "Revolution." They'd gotten disinterested in touring by 1968, so they made these new things called videos and gave them to only one TV program in the United States. Not to "The Ed Sullivan Show," which had helped launch Beatlemania and the British Invasion four years before but to the Smothers Brothers.

And that same year, George Harrison of The Beatles did show up unannounced, not to sing but to support Tom and Dick in their fight against the CBS censors, fights which, by then, had become almost legendary.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "THE SMOTHERS BROTHERS COMEDY HOUR")

TOM SMOTHERS: Do you have something important...

GEORGE HARRISON: Something very important to say on American television.

T. SMOTHERS: You know, we don't - a lot of times, we don't have the opportunity of saying anything important because it's American television and every time you say something...

(LAUGHTER)

T. SMOTHERS: Try to say something important they...

(APPLAUSE)

HARRISON: Clap, clap, clap, clap, clap, clap, clap. Cue the limes. Well, whether you can say it or not, keep trying to say it.

BIANCULLI: At first, the censored bits were silly like an Elaine May sketch about, ironically, censorship. But quickly, the jokes became political and battle lines were drawn. CBS was like a stern parent placing more and more restrictions on a rebellious teenager. And Tom especially got more rebellious. He and brother Dick and the rest, including head writer Mason Williams, who unveiled his hit instrumental "Classical Gas" on the show, put more meat and meaning into the program or tried to.

A skit poking fun at LBJ got the president to call CBS chairman William Paley in the middle of the night to complain, which, in turn, led to Paley asking the show to ease up on its presidential satire. In return, Paley agreed to break the 17-year blacklist on folk singer Pete Seeger who appeared in 1967 to sing as part of an anti-war medley a new song he'd written called "Waist Deep In The Big Muddy," an obvious allegory about the Vietnam War and Johnson himself.

CBS cut the song. Tom Smothers went to the press to complain. And the following year, in a triumphant performance, Seeger was asked back and was allowed to sing his song.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "THE SMOTHERS BROTHERS COMEDY HOUR")

PETE SEEGER: (Singing) All at once, the moon clouded over. We heard a gurgling cry. A few seconds later, the captain's helmet was all that floated by. The sergeant said, turn around, men, I'm in charge from now on. And we just made it out of the Big Muddy with the captain dead and gone. We stripped and dived and found his body stuck in the old quicksand. I guess he didn't know that the water was deeper than the place he'd once before been.

Another stream had joined the Big Muddy about a half mile from where he'd gone. We were lucky to escape from the Big Muddy when the big fool said to push on. Well, I'm not going to point any moral, I'll leave that for yourself. Maybe you're still walking, you're still talking, you'd like to keep your health. But every time I read the paper, them old feelings come on. We're waist deep in the Big Muddy. The big fool says to push on.

Waist deep in the Big Muddy, the big fool says to push on. Waist deep in the Big Muddy, the big fool says to push on. Waist deep, neck deep, soon even a tall man will be over his head. We're waist deep in the Big Muddy. The big fool says to push on.

BIANCULLI: Other segments produced for the show never saw the light of day or at least the prime time of night. For its first show after the violence-filled 1968 Democratic National Convention, "Comedy Hour" had Harry Belafonte sing a medley of Calypso songs with reworked lyrics to reflect the disarray and dissent in America while news footage of police brutality and student protests was projected behind.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "THE SMOTHERS BROTHERS COMEDY HOUR")

HARRY BELAFONTE: (Singing) Lord, don't stop the Carnival. Lord, don't stop the Carnival. Carnival's an American bacchanal. Lord, don't stop the Carnival. People should not live under the big gun. Lord, don't stop the Carnival. You know, there's another song we can all hum. Lord, don't stop the Carnival. It goes we shall overcome. Lord, don't stop the Carnival. We shall overcome. Lord, don't stop the Carnival. Let the people see the (unintelligible). Lord, don't stop the carnival. See how the country's being run. Lord, don't stop the carnival.

BIANCULLI: That never made it to air, nor did a comic sermonette by comedian David Steinberg, whose mortal sin to CBS was making fun of religion at all. His first sermon got more negative mail than anything in the history of TV up to that point. When Tom asked him back, CBS ordered there be no sermon. Steinberg delivered one anyway about Jonah and the Whale.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "THE SMOTHERS BROTHERS COMEDY HOUR")

DAVID STEINBERG: Now, here there are two concepts that we must deal with. There is the New Testament concept and the Old Testament concept. The Old Testament scholars say that Jonah was, in fact, swallowed by a whale. The gentiles, the New Testament scholars, they say, hold it, Jews, no. Jonah wasn't - Jonah - they literally grabbed the Jews by the Old Testament.

(LAUGHTER)

BIANCULLI: Not only was that sketch cut, but the entire show was pulled from the air. And shortly thereafter, the Smothers Brothers were fired. They took CBS to court for breach of contract and eventually won a settlement close to $1 million, but they lost their platform but not before influencing and leading to all satirical political shows to come from "Saturday Night Live" to Jon Stewart, Stephen Colbert, John Oliver and Samantha Bee.

"Comedy Hour" also contributed one of the best political satires ever, a literal running gag in which series regular Pat Paulsen ran for the presidency. He started as the show's editorialist making quick points about everything from gun usage...

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "THE SMOTHERS BROTHERS COMEDY HOUR")

PAT PAULSEN: A gun is a necessity. Who knows, if you're walking down the street, you'll spot a moose.

(LAUGHTER)

BIANCULLI: ...To the mandatory draft, which was dragging young men into the Vietnam War.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "THE SMOTHERS BROTHERS COMEDY HOUR")

PAULSEN: What are the arguments against the draft? We hear it is unfair, immoral, discourages young men from studying, ruins their careers and their lives. Picky, picky, picky.

(LAUGHTER)

BIANCULLI: By the time Paulsen ran for president, he was doing things other candidates were doing like attacking the press and denying his true motives.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "THE SMOTHERS BROTHERS COMEDY HOUR")

PAULSEN: The radio and press have once again chewed off more than they can bite. They continue to confuse personality with politics. They seem to assume that I am lying when I state that I am not a candidate for the presidency.

(LAUGHTER)

PAULSEN: True, all the present candidates once denied they had any intention of running. But the fact that I am also a liar doesn't make me a candidate.

BIANCULLI: Pat Paulsen didn't succeed in his run for the presidency, but Richard Nixon did in 1968. And the Smothers Brothers welcomed him sort of.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "THE SMOTHERS BROTHERS COMEDY HOUR")

DICK SMOTHERS: And history has shown us that almost every president begins his term in office with the support, the absolute support of the entire nation and free from slanders and jokes.

T. SMOTHERS: That's right, Dicky. And for the start of his term, we are going to give our President Nixon our full support and lay off the jokes entirely.

D. SMOTHERS: That's right. He's going to be in office for at least four years, and I'm sure we'll be able to get around to him a little bit later.

(LAUGHTER)

BIANCULLI: Nixon did last four years and a few more. But the Smothers Brothers were gone within six months of Nixon's election, fired in 1969 as the victim of their own outspokenness. Yet on their final show, Dick Smothers read a letter he and Tom had gotten from a former President Johnson. These days, President Donald Trump responds to "Saturday Night Live" skits with angry tweets. Back then, former President Johnson, reflecting on his treatment by the Smothers brothers, responded this way.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "THE SMOTHERS BROTHERS COMEDY HOUR")

D. SMOTHERS: (Reading) It is part of the price of leadership of this great and free nation to be the target of clever satirists. You have given the gift of laughter to our people. May we never grow so somber or self-important that we fail to appreciate the humor in our lives.

(APPLAUSE)

BIANCULLI: Happy anniversary, "Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour," and thanks for everything.

(SOUNDBITE OF TV SHOW, "THE SMOTHERS BROTHERS COMEDY HOUR")

DICK AND TOM SMOTHERS: (Singing) The war in Vietnam keeps on raging. Blacks and whites still haven't worked it out. Pollution, guns and poverty surround us. No wonder everybody's dropping out. But we're still here. Oh, yeah, we're still here. We face the same old problems, but we're still here. That weekly gripe is stretching out before us.

DAVIES: David Bianculli is the author of the "The Platinum Age of Television: From 'I Love Lucy' to 'The Walking Dead,' How TV Became Terrific" and of "Dangerously Funny: The Uncensored Story of 'The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour.'"

DAVE DAVIES, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. The writer and director Ousmane Sembene, who died in 2007, is the most famous and acclaimed black African filmmaker. His first film, "Black Girl," which came out in 1966, was instantly hailed as a cultural breakthrough. A new, restored version of the film is now out on DVD, Blu-Ray and iTunes streaming. Our critic at large John Powers says "Black Girl" isn't merely a landmark but a movie that still packs a wallop.

JOHN POWERS, BYLINE: We can all name movies that take place in Africa, from the many adventures of "Tarzan" to Oscar-winning hits like "Out Of Africa." But these are not movies that actually come out of Africa. They were made by outsiders looking in. In fact, I'd wager that most Westerners have never seen an African story filmed from the inside. There's no better way to correct this than "Black Girl," the taut, moving 1966 film that's widely regarded as the first ever fiction feature by a black African director. It was written and directed by Ousmane Sembene, a brilliant Senegalese auteur who wasn't merely the godfather of African cinema but probably the greatest artist it has yet produced.

Now out on DVD, Blu-Ray and iTunes streaming in a gorgeous new restauration from Criterion, Sembene's debut feels as timely today as it did half a century ago. "Black Girl" centers on Diouana, a young illiterate Senegalese woman, played by the lovely Mbissine Therese Diop, who has worked for a French colonial couple in the capital city of Dakar. She's thrilled when they ask her to move with them to the Riviera. Filled with fantasies of her new life, she dons high heels and her best dress. She's going to be French. Diouana soon discovers the chasm separating her dreams and reality. Not only do her bosses live in a high-rise apartment instead of the villa they'd enjoyed in Africa, but the France she now inhabits is the space in which she cooks and cleans, an imprisoning kitchen, bath and living room that offer teasing glimpses out the window of the sea.

When Diouana is not being publicly shown off like an exotic pet, her mistress privately treats her like a slave. She rebels, but what can she do? She can't even read, let alone answer, the letters from her mother back in Senegal. Her employers do that for her. Of course, there's nothing more familiar than masters treating their servants badly. But what made "Black Girl" groundbreaking in its day, and still gives it an incandescent power, is that these are black Africans telling their own story and telling it with a searing passion. Although Sembene is clearly making a political point about the West's dehumanizing treatment of poor Africans, he never lets his heroine become an abstraction. We feel her pain, humiliation and anger at having her humanity invalidated.

One reason that Sembene could pull this off was that, by the time he made "Black Girl," he was a man in his 40s who knew life. This was no film school brat but the son of a poor Muslim fisherman who'd fought with the Free French forces during World War II, stowed away to do manual labor in France, returned to Senegal in time for independence in 1960, became a largely self-taught writer - his 1960 novel, "God's Bits Of Wood," is tremendous - and then became a filmmaker because so many of his countrymen couldn't read. To reach them, he needed to make movies, and that's just what he did. Over the next decade, Sembene would go on to make richer and more complex works than "Black Girl."

You should be sure to see his 2004 feminist masterwork "Moolaade." But this first one remained the foundation stone. It put an entire continent on the movie map and showed other would-be African filmmakers what was possible. It opened up the world, and it did this with an artistry startling in a new director. Beautifully shot by Christian Lacoste, this movie about black people and white people becomes a symphony in blacks and whites, from the black-and-white tile floors to the black patterns on Diouana's white dresses to the newspaper article about her that appears near the end. The whole story is encapsulated in the African mask that Diouana gives to her mistress on her first day of work. Each time we see it, its emotional charge has changed until the mask has gone from being a gesture of appreciation to a symbol of angry rebellion.

In the process, "Black Girl" radically changes our perspective. As Westerners, we begin the movie thinking we're watching Africans, but we realize that Africans like Sembene have been watching us, too, and know us far better than we know them.

DAVIES: John Powers is film and TV critic for Vogue and vogue.com.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

DAVIES: On Monday's show, advertisers and marketers already track our shopping behavior online, but businesses are now tracking our behavior elsewhere, through apps on our phones.

JOSEPH TUROW: They track how you're walking through the store, where you are and can even change the price on goods.

DAVIES: We'll talk with Joseph Turow about his new book, "The Aisles Have Eyes." Hope you can join us. FRESH AIR's executive producer is Danny Miller. Our technical director and engineer is Audrey Bentham additional engineering support from Joyce Lieberman and Julian Herzfeld. Our associate producer for online media is Molly Seavy-Nesper. Roberta Shorrock directs the show. Terry Gross returns Monday. I'm Dave Davies.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.