Contributor

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on June 23, 2008

Transcript

DATE June 23, 2008 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

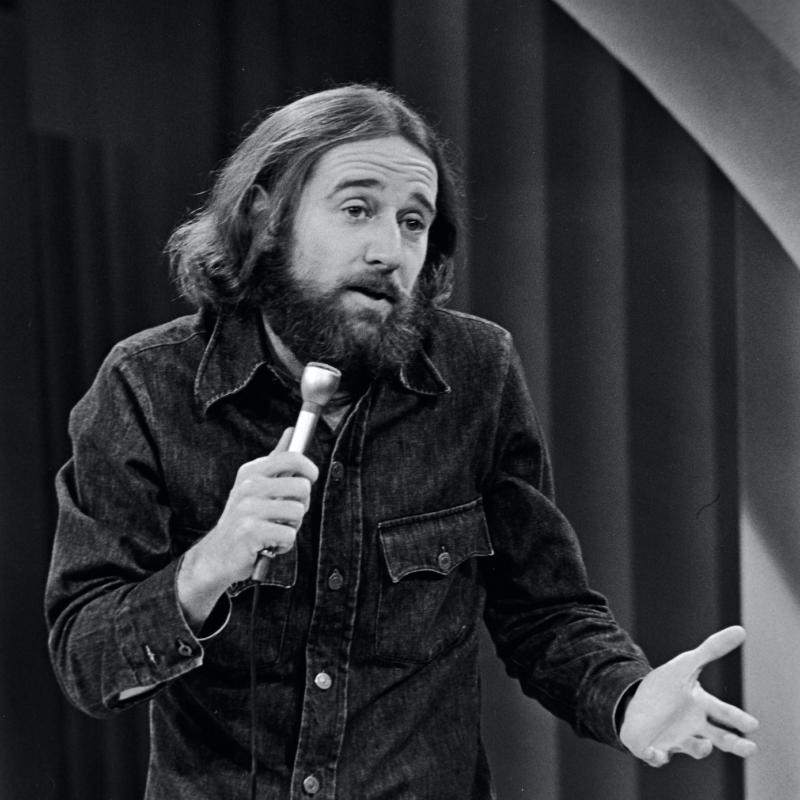

Interview: George Carlin, from two separate interviews, after

his death at age 71

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

We're going to remember the comedian and actor George Carlin, and listen back

to a couple of his FRESH AIR interviews. Carlin died Sunday of heart failure.

He was 71. Last week he had been named the recipient of the Mark Twain Prize

for American Humor, which he was to receive at the Kennedy Center in November.

Carlin was one of the more popular and influential comics that emerged from

the 1960s counterculture. His early humor was often about drugs. His long

ponytail became a trademark. He went on to skewer euphemistic language and

political correctness. He made popular comedy albums and wrote best-selling

humor books. Carlin believed in free speech, including the open use of

expletives, and he was at the center of a famous Supreme Court case about his

famous comic monologue "Seven Dirty Words You Can Never Say on Television. In

1973 the Pacifica radio station in New York, WBAI, played this monologue.

After a complaint was filed the FCC put WBAI on notice, threatening possible

sanctions against the station if subsequent complaints were received. WBAI

appealed the decision. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the FCC,

establishing the regulation of indecency on broadcasts. When I spoke with

George Carlin in 2004, we listened back to this 1972 recording of Carlin's

monologue. We, of course, bleeped the words that made this routine famous.

(Soundbite of George Carlin monologue)

Mr. GEORGE CARLIN: There are 400,000 words in the English language, and

there are seven of them you can't say on television. What a ratio that is.

Three hundred and ninety-nine thousand, nine hundred and ninety-three to

seven. They must really be bad. They'd have to be outrageous to be separated

from a group that large. All of you over here, you seven, bad words. That's

what they told us they were, remember? `That's a bad word.'

No bad words. Bad thoughts, bad intentions and words. You know the seven,

don't you, that you can't say on television? (Censored by station)...huh?

(Soundbite of applause)

Mr. CARLIN: Those are the heavy seven. Those are the ones that'll infect

your soul, curve your spine and keep the country from winning the war.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: George Carlin, welcome to FRESH AIR.

Mr. CARLIN: Thanks, Terry.

GROSS: Can you talk about what led to this routine, like what you were

thinking about, how you wrote it?

Mr. CARLIN: Well, I don't really know that there was a eureka moment or

anything like that. What happened was, I'd always held these attitudes, I've

always been sort of anti-authoritarian and I really don't like arbitrary rules

and regulations that are essentially designed to get people in the habit of

conforming and obeying authority blindly. So I have always resisted that in

my life as a child, as an adolescent and as a young adult. And so I held that

attitude. That's the fertile ground for all of this.

Secondly, I have a strong interest in language that is, in part, genetic, in

part fostered by my mother. And I have always taken great joy in looking more

closely at language. So those things were in place.

On these other things, we get into the field of hypocrisy, where you really

cannot pin down what these rules they want to enforce are. It's just

impossible to say, `This is a blanket rule.' You'll see some newspapers print

"F--K." Some print "F**K." Some put "F---." Some put the word "bleep." Some

put "expletive deleted." So there's no real consistent standard. It's not a

science. It's a notion that they have, and it's superstitious. These words

have no power. We give them this power by refusing to be free and easy with

them. We give them great power over us. They really, in themselves, have no

power. It's the rest of the sentence that makes them either good or bad.

GROSS: In your 1972 recording, you talk about how it's perfectly OK to say,

`Don't prick your finger,' but you can't say, `Don't finger your blank.'

Mr. CARLIN: Mm-hmm. Yeah, you can't reverse the two.

GROSS: You can't reverse the two words. So comics work with the power of

words.

Mr. CARLIN: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: And, in a way, the fact certain words are supposed to be taboo, as you

point out, that gives them power.

Mr. CARLIN: Yes. That's right.

GROSS: And that makes those words more powerful for you when you want to use

them.

Mr. CARLIN: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: So do you feel like you've been able to work with the taboo nature of

certain words and, you know, make that work in your favor?

Mr. CARLIN: Well, what...

GROSS: Like in that classic routine?

Mr. CARLIN: Yeah. That is an interestingly disguised way--and I don't mean

you were trying to deceive me or anything--but it's a disguised way of saying,

`Well, don't some people just use these for shock value?' You get this phrase

all the time from interviewers, shock value. Well, shock is a kind of a

heightened form of surprise, and surprise is at the heart of comedy. So if

you're using the word in a way to heighten the impact of the sentence or

season the stew, they are, after all, great seasonings. There are sentences

that, without the use of hell or damn even, lose all their impact.

So they have a proper place in language. And in my case, I just like them

because they are real and they do have impact. They do make a difference in a

sentence. But if you're using them for their own sake, that's probably kind

of weak. If you're using them in some way that you feel enhances what you're

doing and delivering, that's another thing.

GROSS: Did you ever expect that that comedy routine would be actually played

on the radio, and it would be part of a case that made it all the way to the

Supreme Court and that it would become as important and famous a case as it

became?

Mr. CARLIN: Well, I knew that it wasn't out of the question that it may be

played on the radio. FM radio stations at that time--and there were

commercial ones who qualified as what was called underground radio. And an

awful lot of liberties were taken with music, too, music that had very--I

don't--God, I hate the words "explicit" and "graphic," but those are the words

that would be used by someone to describe those kinds of songs, those lyrics.

I knew there was a chance, but, of course, you know, no one ever sees other

things coming that are unexpected and larger, you know. I just knew that I

had done a piece that summed up my position very well and sort of had a

nice--it had a wonderful rhythmic--the reading of those seven words, the way

they were placed together had a magnificent kind of a jazz feeling, a rhythm

that was just very natural and satisfying the way those syllables were placed

together. And so I knew I had done something that was making an important

point about the hypocrisy of all of this.

GROSS: Before we get back to our 2004 interview with George Carlin, let's

listen back to an excerpt from his 1990 FRESH AIR interview in which we also

talked about the court cases surrounding the broadcast of his "Seven Dirty

Words" routine.

Did the judges in the various trials get the point, do you think?

Mr. CARLIN: Absolutely not. I don't think they even listened. I'm sure

they didn't listen to the record to hear it in its fullest and best context.

I'm sure they read portions of the transcript. It's in the interest, I guess,

of the white male, religious corporate paramilitary state that we live in, to

control us. And the FCC, of course, has control only over broadcast media.

And I guess they found a way to interpret that form of expression differently

from the printed word and the spoken word.

The argument, which I think is specious, is that because this goes out into

the home, that somehow it's going to injure someone morally if it comes

through the speaker. They don't take into account the fact that there is an

on/off switch on every radio and there is a station selector knob for changing

the station. The man who made the complaint, one of these moral commandos, a

professional moralist who wants us to live his way, sat in his car with his

son and listened to the entire broadcast. And I assume they were not morally

degraded in any way. I assume the child has developed in a normal way in

spite of listening to that routine. So where is the argument? I don't follow

the damage. I don't see where the damage occurs in this language being used.

GROSS: You know, Lenny Bruce always said that when he was up on obscenity

charges...

Mr. CARLIN: Yeah.

GROSS: ...that he wished he could perform the material for the judges, you

know, because they were hearing, you know, either reading transcriptions or

they were hearing people quote the material.

Mr. CARLIN: A cop was doing his act poorly.

GROSS: Right. That's it, yeah, yeah. And, you know, Bruce really felt,

`Well, if they're going to get what it's about they have to hear me do it.'

Did you feel that way yourself?

Mr. CARLIN: Sure. Well, I feel that the thing was rigged to start with, you

know.

GROSS: Uh-huh.

Mr. CARLIN: I mean, I think the outcome was inevitable. But surely it would

have been fairer to the process to listen to the recording. And the other

thing about it is, there was a warning given, there was a disclaimer given by

the radio station saying that `there'll be language on this next recording

which you may find offensive.' There was the point made that it was in the

context of speaking about protected speech. And certainly in that case that

has to be a redeeming artistic feature, which is one of the tests for

obscenity. Of course they didn't test it for obscenity. They called it

indecency and got around the obscenity law in that manner.

GROSS: Now, you were arrested in Milwaukee in 1972.

Mr. CARLIN: Yeah, now that was more for public, what you call it, disorderly

conduct. The concert was outdoors and the speakers--the concert setting

outdoors was in a larger setting of a fest, a festival, a summer fest.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. CARLIN: And so the complaint was made on the basis of the fact that the

language coming from these speakers flowed out of the concert area into the

area of the general public, and the policemen felt that was wrong. I think

his idea was, he said, `There were mothers listening to this,' which I don't

understand at all. But at any rate, we just waited. As the lawyer told me,

he said, `We're going to wait a few months on this case until a judge comes

around who understands the First Amendment.' And apparently in Milwaukee that

took about six months.

GROSS: Did you expect to be arrested?

Mr. CARLIN: No.

GROSS: Did you have any idea this was coming?

Mr. CARLIN: Oh, absolutely not. No, and I think it was a spur of the moment

decision on the part of one policeman.

GROSS: And how did they come get you?

Mr. CARLIN: Oh, they just came backstage. My wife came out onstage during

the show to warn me that they were back there. She came out, ostensibly, to

bring me a glass of water. And it was a large, kind of unruly audience and

everything, so an interruption like that wasn't particularly damaging to the

flow of the show of anything. So she just got me aside and said, `There's

police backstage and they're going to arrest you.' So I went offstage a

different way where they weren't waiting. And at that time I was still a user

of illegal substances. And so I got rid of what I had on me so that the only

arrest would be for this spoken violation and not for something else, which

they would have loved to catch me doing.

GROSS: You went to Catholic school, right, as a boy?

Mr. CARLIN: Yeah, I went to a rather progressive Catholic parochial school,

which was very much different from the kind of horror stories we hear about

Catholic schools, especially in that era. I went to a school where the nuns

were specially trained. They had special master's degrees from Catholic

university. We were taught religion, but we didn't have uniforms. We didn't

have the sexes in different classrooms. There was no corporal punishment. It

was very progressive. Certainly for the 1940s, it was progressive because

what it amounted to was that the Catholic Church was actually experimenting

with humane treatment.

And by the way, my third grade teacher, Sister Marie Richard, will be at my

show in Davenport, Iowa, this Sunday. I've been in touch with her over recent

years. She's now called Malita Conlon. She wears street clothes, but she's

still part of the Dominican Teaching Order. And she encourages me. She says,

`I know that what you do is sort of in service of a larger objective.' And she

has given me--if I needed it, which maybe I did--a kind of imprimatur from my

former Catholic teachers that what I'm doing is OK.

GROSS: So you're not going to worry about embarrassing her with your

material?

Mr. CARLIN: No, she's been at the shows before and I always warn her. And I

told her this time `Sister, it's a little rougher than it was two years ago.'

She says, `You're getting rougher?' And I said `yes.' But there are a few

things that, when I think they're like just too harsh I'll take them out when

I do--she'll have a lot of priests and people with her, and I don't like

making people uncomfortable. I don't think I have an obligation to force what

I think is correct or OK into other people's lives. With Sister Conlon it's

OK, but if she's going to have guests with her I'll probably try to protect

them, you know. I don't really want to injure someone.

GROSS: George Carlin recorded in 1990. We'll hear more of his 2004 interview

after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: We're remembering comic George Carlin. He died of heart failure

yesterday at the age of 71. Let's get back to our 2004 interview with him.

Do you remember how you were first exposed to four-letter words and what your

reaction was when you first were?

Mr. CARLIN: Well, I was--I grew up in a part of New York City that's a very

interesting neighborhood. I lived--literally my front door was across the

street--and I mean literally in its real sense here--literally across the

street from Teachers College of Columbia University. And all around me to the

south I had Columbia University Teachers College, Barnard College; Juilliard

School of Music was around the corner, the original location. Riverside

Church, the 23-story interdenominational cathedral, the Gothic cathedral, was

at the end of my street. Union Theological Seminary, the largest seminary in

the world of, again, interdenominational clergy. And around the corner the

Jewish Theological Seminary, the largest Jewish seminary in the world. St.

John the Divine was nearby, and Grant's Tomb. So it was a highly

institutional neighborhood full of learning and serious people.

Immediately to the north down the hill we had the beginnings of Harlem. We

called our section white Harlem because we thought it sounded tough, but there

were cross-pollination between these two groups. I lived very close by

Cubans, Puerto Ricans and Dominicans, on the one hand, and blacks on the

other. And when you're in those neighborhoods at the border--my part was a

little Irish enclave, just a little wedge-shaped Irish enclave in the middle

of all that, highly populated because we were quite fertile folks. Lot of

kids, lot of kids on the street. And when you live near the border between

all black and all white, you don't have the attitudes that the people who are

insulated and isolated in the center of those areas have. Those are people

who are not in contact day to day to day to day with the opposite.

But we did have contact all the time, and when you're on the border between

two cultures, you sort of learn to live together. You have a common code of

the streets, in this case. And so I heard my language from the realistic

people in the neighborhood--my big brother, for one, but his friends and then

all of the tiers and strata of the brothers and sisters under him. You know,

everybody you knew had three or four brothers and sisters, and each of them

were the same age as your brothers and sisters. So it was kind of

interesting, but that's where I got a realistic feel and look at the world.

GROSS: Did language get you into trouble as a kid?

Mr. CARLIN: Well, I--because I liked language--as I was saying, my

grandfather wrote out all of the works of Shakespeare in his adult life

longhand because of the joy it gave him--those were his words--`I do it for

the joy it gives me.' So that gene was active in our family, so I had that, as

I described earlier. But I then started collecting exotic combinations of

curses that I heard in my neighborhood. I was probably 13 or 14 at the time.

And there were guys who would put together a sentence in the heat of anger or

in some ornate, descriptive passage in something they were describing, and

they would have an adjective or two, self-hyphenated; they would have made up

a form and tacked it onto some noun that it didn't really go with, and the

rest of the sentence might have been some colorful verb that was, again, very

inventive street language. And some of them were very colorful and exotic and

different. They weren't just flat-out curses.

So I heard these and I started writing them down. In another situation where

I could tell you what they were, you'd understand a little better even what I

mean. But I wrote them down and I had a little list of them--I had about 10

or 12 of them. There are a few I can still remember. But I've had that in my

wallet, and my mother was a snoop and discovered things I had stolen that way

and confronted me with them. But in this case, and looking in my wallet, she

found this list. And I heard her--I came in one night and I opened the door

very slightly in the apartment on the second floor, and I heard her talking to

my Uncle John, and she was worried about me anyway because I was kind of a--I

was getting to be a loose cannon kind of an adolescent, defying, as you will

and must then. And I heard her saying, `I think he may need a psychiatrist,

John. I think we may have to get a child psychologist for him,' because she

was telling him these words and showing him this list. So yeah, they got me

in trouble that way, but at least it was a creative effort.

GROSS: Although your mother was appalled finding this list...

Mr. CARLIN: Mm-hmm, yeah.

GROSS: ...of street words in your wallet, you earlier credited your mother

with having...

Mr. CARLIN: Oh, yes, she was...

GROSS: ...a love of language and helping to instill it in you.

Mr. CARLIN: Yeah.

GROSS: How did her love of language express itself?

Mr. CARLIN: Yeah. And, first of all, just to put it in perspective, the

portion of my life when my mother and I were at odds is when you're supposed

to differentiate yourself from the adult, the parent of the other sex, and I

had no father present in the home, so this was a battle between my mother and

me for my identity sort of, to overdramatize it. But she was wonderful, and

she was my hero. She brought up two boys in the second world war in an

advertising job she had, and she stimulated that thing in me about

language--she would send me to the dictionary. I mean, that was pro forma in

a lot of families--I know that's what you do. But she would say, `Get the

dictionary.'

I asked her once what `peruse' meant. I said, `Ma, what's peruse?' She said,

`Well, get the dictionary in here. Let's get the dictionary.' So I'd look it

up and she'd have me use it in a sentence of my own, and we'd talk about the

root or the origin of it, and which definition was more useful and current and

so forth. And so the next day when I gave her her newspaper--in the evening,

it wasn't a nightly custom, but sometimes I went and bought her a newspaper

when she'd come home from work--I brought it in her bedroom and gave her the

newspaper and I said, `Here, Ma,' I said, `Would you like to peruse this?' And

she said, `Well, maybe I'll give it a cursory glance.' And it was right back

to the dictionary.

And another thing she would do with that newspaper--she'd be reading a

columnist, someone who wrote well, and she would call me into the room and

say, `Look at this. Listen to these words. Look how that word cuts--it just

cuts through that sentence,' and she would make--she would do all these sort

of dramatic--they had an effect on her and she was able to transmit that to me

through her use--she was a person who employed a lot of melodramatic things in

her life. She said, `I should have been on the stage, George. Someday you

must tell my story.' You know?

GROSS: George Carlin recorded in 2004. We'll hear more of the interview in

the second half of the show. Carlin died of heart failure yesterday at the

age of 71. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. We're listening back to our 2004

interview with comedian George Carlin. He died of heart failure yesterday at

the age of 71. Last week he'd been named the recipient of this year's Mark

Twain Prize for American Humor, which he was to receive in November at the

Kennedy Center. He was famous, among other things, for his monologue "Seven

Dirty Words You Can Never Say on Television" and for his skewering of

euphemisms and politically correct language.

When we left off, he'd described how his mother got him interested in language

and using the dictionary. Learning a little Latin helped, too.

Mr. CARLIN: I quit high school in ninth grade, but first year high school

for me had Latin I. And Latin I is when you learn all the vocabulary and when

you learn the declensions of the nouns and the conjugations of the verbs. So

it was elemental. And I learned a lot about root formations and the language

that grew out of the Latin--the romance languages.

GROSS: Why did you drop out of high school in ninth grade?

Mr. CARLIN: I could see that I--they weren't offering anything I really

needed. I wasn't interested in merely having a credential. And I knew I had

the skills I needed, and all I needed to do was to work hard on the English

language, and these skills I had, sharpen them. I had a very strong command

of the language as I was at that time, and I knew that would develop further.

And I knew that I didn't really need all of that stuff that they offered, that

they teach you, to do what I wanted to do. I was very inner-directed and very

self-sufficient. I had an autonomy in my heart that kept me moving in my own

path.

GROSS: Did you know in ninth grade, when you dropped out, that you wanted to

be a comic?

Mr. CARLIN: Oh, yeah, I knew that in fifth grade. I wrote a little

autobiography then. I said, `I want to be a comedian or an impersonator or an

announcer or an actor.' And I had a plan. The plan was radio first because

there's no audience there present. You get away with more. The nerves are

different. Second step would be standup comedy, and once I was good enough at

that, they'd have to let me in the movies, like Danny Kaye. That was my

childhood thought. I thought it was a birthright, and I thought that I had a

path figured out. And the path worked that way. I just realized later I was

a better comedian than I thought, and I could abandon the actor part.

GROSS: Now, I know you made it onto radio before you became...

Mr. CARLIN: Yes.

GROSS: ...famous as a comic. What was your radio persona?

Mr. CARLIN: Well, I was on a--the first job I had was in a

place--Shreveport, Louisiana, which sounds like kind of an easily ignored

place, but it had nine stations. It was a hot radio market, as they said, and

we were number one. I had a 52 share. Imagine that, a 52 share in a

nine-station market in my afternoon show. So it was top 40, but it wasn't as

rigid as top 40 became. It wasn't as--it didn't sound, you know, like a

robot: time, temperature and the label and the name of the artist. You could

be a little bit of a personality, too. So we played top 40, and I was a

very--I was only 18. It was great to be playing the very music that I was

dancing to at night. It was nice to go over to a girl in a situation like at

a bar or something and say, `Would you like me to play a song on the radio for

you tomorrow and dedicate it to you?' It was a little underhanded, but it sure

worked a lot.

GROSS: Works like a charm.

Mr. CARLIN: Yeah.

GROSS: And would you talk your way through the instrumental up to the vocal

of the record?

Mr. CARLIN: Some of the time, sure. Yeah, use you know, the first eight

bars or 16 bars or whatever the instrumental intro was, you bring it up first

for about three or four seconds, then you bring it down. You say, `OK, the

new Connie Francis just came in.' And I'm exaggerating my disc jockey voice.

`And here at 15 minutes past 5 on "The George Carlin Show" on KJEL, we're

going to listen to this brand-new one,' and then, whoom, up with the vocals,

you know? I loved running a tight board. We ran our own boards, and I loved

it. I was so proud of tight cues and segues that were tight, you know. It

was just a point of pride.

GROSS: Now, you've always opposed authority. I mean, you dropped out of

school in ninth grade.

Mr. CARLIN: Hm. Yeah.

GROSS: You joined the military. You were court-martialed twice in the

military.

Mr. CARLIN: Hm. Yeah, three times.

GROSS: Three times? OK.

Mr. CARLIN: Yes.

GROSS: Why would somebody who opposes authority so much volunteer to go into

the military, which has such a hierarchical structure?

Mr. CARLIN: Hm. Yes. Well, at that time in our history, there was a draft.

And the way you avoided the draft was to join. It's an odd thing. It sounds

like a paradox, but it's true. The way you stayed out of the military was to

choose when to go in, not to let them decide. See, I wanted the choice to be

mine. I didn't want to wait to--in New York, the draft pool was very large,

and therefore you wouldn't be drafted till your early 20s, which would have

interfered with my life plan. I had a little plan when I was 11 years old,

and I was working through it in my teenage years. And I said, well, I'm not

going to get to do this if they're go to draft me with all these other guys

are 20, 21. I joined at 17 to get what they called then--get the military

obligation out of the way.

GROSS: And when you got in there, how'd you do inside? You mentioned you

were court-martialed three times. How did you respond to the authority within

the military?

Mr. CARLIN: Poorly to the authority. I was very good at the thing they

trained me for, which was electronics and analog computers. There was a

system called the K system bomb system on the B-47, and I was trained in a

very elite squadron, I'm proud to say. It's one of the few conceits I have

about myself, but it is a genuine one. I qualified for a highly elite school

and passed with the highest T score they'd ever had, and therefore--but I

loved it because of the theory involved. It was all blackboard. It was none

of this screwdriver stuff.

So when I got to my base to practice this art, science, that they taught

me--spent a lot of money on me--right away they tell you, `Pick this up, put

it over there. Put those there. And just take the'--I didn't care for that,

and so I became a disc jockey in a downtown commercial station instead when I

was 18. And I had already begun my career while I was getting my military out

of the way. But I was a behavior problem there, just as I was in school,

because I didn't accept arbitrary orders from people who I thought were

possibly inferior.

GROSS: Now there's a lot in the universe that you find pretty absurd, and

you...

Mr. CARLIN: Hm. And wonderful.

GROSS: And wonderful. But when it comes to the absurdity or the ridiculous

aspects of life...

Mr. CARLIN: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...you're not going to be looking to religion to help you provide

meaning or a sense of...

Mr. CARLIN: No.

GROSS: ...your place in the world. Is there anything that you do turn to to

help provide, you know, meaning or a sense of like, you know, where do you fit

in, or what are you doing here?

Mr. CARLIN: Mm-hmm. Yeah. Well, sure. Some time ago I figured out, with

the help probably of some reading that I can't recall now, that if it's true

that we're all from the center of a star, every atom in each of us from the

center of a star, the we're all the same thing. And even a Coke machine or a

cigarette butt in the street in Buffalo is made out of atoms that came from a

star. They've all been recycled thousands of times, as have you and I. So if

that is true, then I am everywhere in the universe in an extended sense, and

therefore it's only me out there. So what is there to be afraid of? What is

there that needs solace-seeking? Nothing. There's nothing to be afraid of

because it's all us.

So I just have that as a backdrop, and I don't have to go to it or think of it

consciously. I've kind of accepted this idea that I'm perfectly safe and that

life and nature have waves and troughs; there are ups and downs, left and

right, black and white, night and day, fall and winter, positive and negative.

Everything has an opposite. If it's a bad time, I'll have a good time coming.

If it's a good time, I'm prepared to have a bad time to sort of pay for it.

So nothing--it doesn't really--they don't really upset me a lot, these, you

know, things that happen in our lives.

GROSS: You know, it's great the way you described it as how, like, the whole

world is really you; like, we're all of the same molecules and everything.

Mr. CARLIN: The whole universe, yeah.

GROSS: The whole universe is you. It's this great mix of, like, narcissism

and mysticism rolled into one, the way you put it.

Mr. CARLIN: Sure. And that's kind of--yeah. And that's essentially what we

all are. The trouble is we have been separated from that universe by being

born and given a name and an identity and being individuated. We've been

separated from the oneness, and that's what religion exploits, that people

have this yearning to be part of the overall one again. So they exploit that.

They call it God. They say He has rules. And I think it's cruel. I think

you can do it absent religion.

GROSS: Now, you've had your time spent with drugs and alcohol.

Mr. CARLIN: Mm-hmm. Yes.

GROSS: And, you know, a lot of people in entertainment burn out or end up

killing themselves, you know, intentionally or inadvertently...

Mr. CARLIN: Hm. Yeah.

GROSS: ...through that burnout with the help of drugs and alcohol. You've

also had three heart attacks.

Mr. CARLIN: Yes.

GROSS: So I'm wondering, are you ever nervous about death or illness or the

prospect of being, you know, physically diminished at some point?

Mr. CARLIN: Mm-hmm, mm-hmm. Yeah.

GROSS: Is this the kind of thing, like, you have anxiety about, or do you

just kind of like, `whatever'?

Mr. CARLIN: Well, I don't like the idea of not being here anymore because I

do have such a joy in living my life. I love my writing. I love to sit alone

and write. I love Sally, and we have a wonderful love together. And I don't

want to leave those things, so that will be a hard thing to face if I have a

moment or two or a month or a year to face it. But I don't necessarily have

anxiety about those things.

I would hate to lose my power of speech because it is sort of my identity for

me, forgetting the world for the moment. I feel whole when I'm able to speak

my thoughts. That would bother me. But if I were still able to somehow type,

I could find some joy, and some--you know, it would be OK. If I couldn't,

then there's these people who are completely paralyzed, but they can operate a

keyboard by moving their eyes. I don't know if you've ever seen that.

They're probably not very common machines.

GROSS: Mm-hmm, mm-hmm.

Mr. CARLIN: But you can do that. So I thought, `Well, even if I'm

paralyzed, I can sort of, like, write a few paragraphs each day,' you know?

So these are, you know, odd, extreme thoughts, but those are the thoughts I

think of when I contemplate these fates.

GROSS: We're listening back to a 2004 interview with George Carlin. He died

yesterday of heart failure. We'll hear the final part of the interview after

a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

GROSS: We're remembering comic George Carlin. He died of heart failure

yesterday at the age of 71. This is an excerpt of his 1972 album "AM and FM."

He's talking here about daytime TV.

(Soundbite of "AM and FM")

Mr. CARLIN: And then there's "Let's Make a Deal," the seat of greed in

America. You've seen the people on "Let's Make a Deal." You should see the

ones they don't let on the show.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CARLIN: `Take them away.' You know, but you've got to be a little bit

dingy, I think, to be 43 years old and standing up there dressed like a

radish, you know.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CARLIN: And the ladies, God love them, they show that greed when Monty

shows the money. `Hi, I'm Monty Hall and I have $500.'

(Soundbite of whoosh)

Mr. CARLIN: `Not anymore, Monty.' `OK, you have the $500, what would you

like to do? Keep the $500 or do you want to buy what Jay has in his box he's

bringing down the aisle? Jay, you want to bring that box on down? Jay, look

out for the cord. Jay, look out. Jay!

(Soundbite of tumbling noise)

Mr. CARLIN: Well, now we know what Jay had in the box. It was a cheese

straightener. Deluxe model, too. OK, what do you want to do? Do you want to

keep the cheese straightener or do you want the $500, or do you want door

number one, door number two, or door number three?' `Oh, Christ! Oh, Monty,

Monty, what were the doors again?'

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: George Carlin recorded in 1972. Let's get back to our 2004 interview

with him.

Who were the first comics that you heard where you thought, `They nailed it.

This is what life is about'? Like, they just described life.

Mr. CARLIN: Yeah. Well, you know, I don't know--I know that the gist of

your question, I can answer. Of course, comedy changed in the 1950s when the

individuals emerged, and nobody was all the same anymore. It used to be very

same, very safe and very same. And then Lenny Bruce, Mort Sahl, Nichols & May

and a lot of other people in the improv groups and some underground press and

so forth took hold of comedy and changed it. And so it was that crop in the

'50s--I was then approaching my 20th birthday. And Lenny Bruce was, of

course, the one who inspired me the most because I saw for the very first time

utter and complete honesty on a stage. And it was a brilliant form of it. It

wasn't just honesty, it was great satire. Even in his days of--just his

parodies were great.

But then he started talking about religion and things, and I thought, `Boy,

that's wonderful to know that you can do that; that it can be done.' I didn't

say, `Well, I'm going to do that, too.' But I sort of said, `OK, now I know

that.' And it really did help me later to decide to be myself.

GROSS: How much do you think your comedy has changed from when you first

started doing standup?

Mr. CARLIN: Well, of course, the times helped--you know, the change is

illustrated by the times. I began in 1960. I went through about eight or

nine years of what essentially were the extended 1950s, sort of a button-down

period. But that was when the country was changing. I was 30 in 1957. The

people I was entertaining were in their 40s, and they were the parents of the

people who were 20, 18, in college, beginning to change the nature of our

society to a great extent. So I sided more with them because I was

anti-authority, and I just let myself revert to my deferred adolescence and be

one of them in terms of my work rather than these people I really disliked,

who I was entertaining, these 40-year-old plus people.

So that's how my comedy has changed. The times were safer, and I was a safer,

mainstream comic in the '60s. And then I became this other person, who was a

little more honest and open with language and his thoughts, you know.

GROSS: Were you performing to older audiences because those were the people

who could buy the tickets in the places that you were performing?

Mr. CARLIN: Well, no, not strictly speaking. What happened was this--and I

can do this briefly for you. I had always been this law breaker, outlaw-type

kid and adolescent--and Air Force guy, as you pointed out--never stuck by the

rules, always swimming against the tide. But I had a mainstream dream, and my

dream was to be like Danny Kaye in the movies or to be like Bob Hope in the

movies. So I never put those two things together. I never saw that they

didn't go together. And I followed this other dream in the way that you did

because the only way you could do it was to please people with mainstream,

safe comedy kits, what the period demanded and got. So I did that until the

two became--it became an untenable situation. I could no longer be myself

inside and serve these other things. And when I saw the mistake, I went about

correcting it in a slow and orderly manner. It took about two or three years

for my changes, as it were, to take place.

GROSS: Well, George Carlin, I'd like to ask you to end our interview by

reading the final piece in your new book.

Mr. CARLIN: Oh, sure. OK.

GROSS: And the book is called "When Will Jesus Bring the Pork Chops?" And

this piece is called "The Secret News." And you're welcome to say anything

about writing it before you read it or to just read it, whatever you prefer.

Mr. CARLIN: I have a big file called News, and it has a lot of odd news

formats. And one of them was this one called "The Secret News." And this was

actually written and designed to be on an album, maybe, a studio-type album,

where you could use sound effects and you were simulating actual broadcasting.

But it works this way, too, with the sound effects indicated verbally. I'll

do that for you. It's called "The Secret News," and we hear a news ticker

sound effect.

(Soundbite of Carlin making news ticker effect)

Mr. CARLIN: And the announcer whispering, saying, `Good evening, ladies and

gentlemen. It's time for "The Secret News." And the news ticker gets louder,

and he goes, `Sh.' And the ticker lowers. "Here's the secret news. All

people are afraid. No one knows what they're doing. Everything is getting

worse. Some people deserve to die. Your money is worthless. No one is

properly dressed. At least one of your children will disappoint you. The

system is rigged. Your house will never be completely clean. All teachers

are incompetent. There are people who really dislike you. Nothing is as good

as it seems. Things don't last. No one is paying attention. The country is

dying. God doesn't care. Sh."

GROSS: George Carlin, thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. CARLIN: Sure. Thank you. I always appreciate--I'm not flattering

here--an intelligent interview, and thank you for that.

GROSS: George Carlin, recorded in 2004. He died of heart failure yesterday

at the age of 71.

You can download podcasts of our interviews on our Web site, freshair.npr.org.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: Ken Tucker on Al Green's new album "Lay It Down"

TERRY GROSS, host:

Al Green's new album "Lay It Down" was produced by a member of The Roots,

Questlove, and features cameos and songwriting collaborations with so-called

neo-soul artists such as John Legend and Corinne Bailey Rae. Rock critic Ken

Tucker calls the result a pleasure. But does it stand up to classic Al Green

records? Here's Ken's review.

(Soundbite of "Lay It Down")

Mr. AL GREEN: (Singing) Lay it down

Lay it down

Lay it down

Put your head on the floor

Lay it down

Lay it down

Lay it down

I just met you...

(End of soundbite)

Mr. KEN TUCKER: At age 62 Al Green has earned the right not only to have

acolytes, but to allow them to give him his proper due, which is to try and

help him build a hit record. To that end he agreed to have Ahmir Thompson,

aka Questlove, the drummer for the hip-hop group The Roots, assemble a group

of performers influenced by Al Green's prime 1970s hit singles. They did him

proud, recording in New York but capturing much of the mucky funk of the high

record studios in Memphis where Green recorded his greatest music with the

producer Willie Mitchell.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. GREEN: (Singing) As I sit and watch my baby

How you do the things you do

Yea, I know deep down in your heart

I never see all you do

I smile and I'm glad

You're the best thing that I ever had

(End of soundbite)

Mr. TUCKER: So with all this pretty music and these deep grooves, what keeps

"Lay It Down" from being a great Al Green album? It's some mystical

combination of spirituality--that is, a lack of it--and the lyrics--that is,

the banality of them. Now, you might say that the man who made a hit by

chanting "love and happiness" over and over doesn't have much need for tricky

wordplay. And you're right, he doesn't. What he does need are sufficient

phrases and refrains into which he can pour his smoldering passion.

That's why one of the best tracks here is the tight, precise construct called

"I'm Wild About You," with its slamming beats and airy room for Al to

improvise grunts and moans over the other nonverbal element, the "woot woot"s

of the backup singers.

(Soundbite of "I'm Wild About You")

Backup Singers: (Singing) Woot, woot

Mr. GREEN: (Singing) No doubt, hey, hey

I'm wild about you, baby

Hey! I'm wild

I'm wild about you, baby

There ain't no doubt

Oh, Lord

(End of soundbite)

Mr. TUCKER: One theme the new album mostly avoids is the explicit

Christianity to which Green, the very active pastor of the Full Gospel

Tabernacle in Memphis, has devoted much of his last 20 years of music making.

The common wisdom is that once Green denied the secular in his music it lost

much of his tension. But in steering him away from God talk, his admirers

have too often replaced it with mere nostalgia, summoning up memories of

previous Green hits rather than moving him forward with new ones.

(Soundbite of "Stay with Me (By the Sea)")

Mr. GREEN: (Singing) Stay with me, my dear

Walk with me and hold me near

It's not as late as it seems

No, no

So why'd you take your love away from me?

Backup Singers: (Singing) La la la

La la la

Mr. GREEN: (Singing) La la la

Backup Singers: (Singing) La la la

Stay with me

Mr. GREEN: (Singing) La stay

Backup Singers: (Singing) La la la

La la la

Mr. GREEN: (Singing) Oh

Backup Singers: (Singing) La la la

Stay with me

Mr. JOHN LEGEND: (Singing) In the morning light

Are shades of white

You're the only one that's right

So what's the meaning of saying goodbye

Backup Singers: (Singing) La la la

(End of soundbite)

Mr. TUCKER: This album's duets with the singers Corinne Bailey Rae and John

Legend--I just played the latter--are the collection's least interesting

tunes. On the other hand, a song written and recorded with yet another

neo-soul singer, Anthony Hamilton, has the right idea. "You've Got The Love I

Need" has a lightness that compels Green to reach for the high notes his

fraying upper register can still attain with an effort which signals his

enduring energy. The lyric, meanwhile, is ambiguous enough to suggest that

Green and Hamilton may be making an entreaty to Jesus as much as to a woman to

be seduced.

(Soundbite of "You've Got The Love I Need")

Mr. GREEN and Mr. ANTHONY HAMILTON: (Singing)

You've got the love I need, babe

You've got the love I need, babe

Yeah

You've got the love I need, babe

You've got the love I need, babe

Mr. HAMILTON: (Singing) Oh, my only friend

The only truth I've know

Oh, you taught me things about me

I never thought I'd know

(End of soundbite)

TUCKER: If in the end "Lay It Down" is an Al Green album for Starbuck stores

that already show a waning desire to push vintage soul acts, it's enough of a

showcase for Green's senior citizen vigor to make you realize anew that it

doesn't matter how old he is or how young his admirers are, it's the vitality

and resiliency of the music that matters.

GROSS: Ken Tucker is editor at large at Entertainment Weekly. He reviewed Al

Green's new album "Lay It Down."

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.