James Fallows: 'China Makes, The World Takes'

Journalist James Fallows, a 25-year veteran of The Atlantic Monthly, is living in China and writing about it. He joins Dave Davies to discuss his recent article "China Makes, The World Takes" — and the booming Chinese factories that are its subject.

Guest

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on October 30, 2007

Transcript

DATE October 30, 2007 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

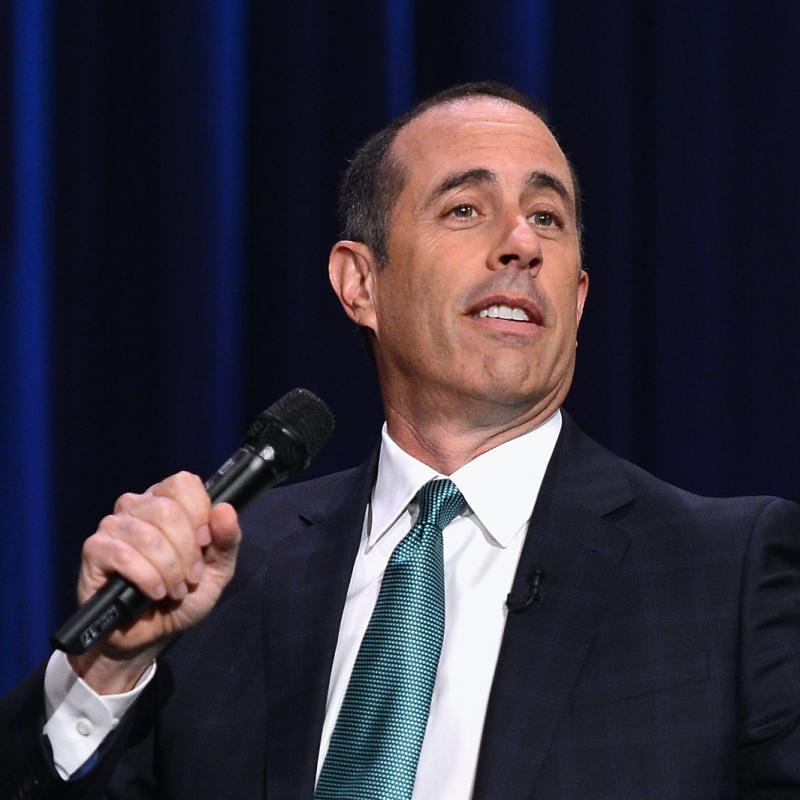

Interview: Jerry Seinfeld discusses career and new movie "Bee

Movie"

DAVE DAVIES, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies, senior writer for the Philadelphia Daily

News, filling in this week for Terry Gross.

It's hard to believe it, but it's been nine years since Jerry Seinfeld made

the last episode of his hit TV series. At 53, Seinfeld is now married, has

three children and has returned to stand-up comedy. But for much of the last

four years, he's worked to bring his unique brand of humor to a new medium.

Seinfeld is a writer, producer and co-star with Renee Zellweger of "Bee

Movie," an animated feature about a bee who learns about life outside the hive

and eventually sues humanity for stealing honey. In this scene, Seinfeld, as

Barry B. Benson, is talking to his parents, played by Barry Levinson and

Kathy Bates, about whether he wants to follow his dad's career path and spend

his life stirring honey.

(Soundbite from "Bee Movie")

Mr. JERRY SEINFELD: (As Barry B. Benson) Dad, do you ever get bored doing

the same job every day?

Mr. BARRY LEVINSON: (As Martin Benson) Son, let me tell you something about

stirring. You grab that stick and you just movie it around, and you stir it

around. You get into a rhythm. It's a beautiful thing.

Mr. SEINFELD: (As Barry B. Benson) You know, Dad, the more I think about

it, maybe the honey field just isn't right for me.

Mr. LEVINSON: (As Martin) And you're thinking of what? Making balloon

animals. That's a bad job for a guy with a stinger.

Mr. SEINFELD: (As Barry) Well, no.

Mr. LEVINSON: (As Martin) Janet, your son's not sure he wants to go into

honey.

Ms. KATHY BATES: (As Janet Benson) Oh, Barry, you are so funny some times.

Mr. SEINFELD: (As Barry) I'm not trying to be funny.

Mr. LEVINSON: (As Martin) You're not funny. You're going into honey. Our

son the stirrer.

Ms. BATES: (As Janet) You're going to be a stirrer?

Mr. SEINFELD: (As Barry) No one's listening to me.

Mr. LEVINSON: (As Martin) Wait till you see the sticks I have for you.

Mr. SEINFELD: (As Barry) I can say anything I want right now. I'm going to

get an ant tattoo.

Ms. BATES: (As Janet) Oh, let's open some fresh honey and celebrate.

Mr. SEINFELD: (As Barry) Maybe I'll pierce my thorax...

Mr. LEVINSON: (As Martin) To honey.

Mr. SEINFELD: (As Barry) ...shave my antenna...

Ms. BATES: (As Janet) Oh, honey.

Mr. SEINFELD: (As Barry) ...shack up with a grasshopper, get a gold tooth

and start calling everybody "dawg."

(End of soundbite)

DAVIES: I spoke to Jerry Seinfeld when he was in Philadelphia recently.

Well, Jerry Seinfeld, welcome back to FRESH AIR. You spent years fine tuning

your, you know, your stand-up material. And I know you work it meticulously.

How is writing a screenplay different?

Mr. SEINFELD: The trouble with it is you have this story, which is such a

nuisance. You know, in stand-up you just tell the funny part, but in a movie

the audience demands that you tell them some sort of story that makes sense.

And this is a tremendous handicap for me, because it frankly doesn't interest

me that much.

DAVIES: The story?

Mr. SEINFELD: Yeah. But you do have to have one, and it has to work. And

the funny thing, I found, is when the story works, the jokes work better. So

I had to work on--the jokes came easily, but figuring out the story of what

happens to this bee and how he gets involved with the humans and how

everything goes wrong and how to make it all come out right in the end, and

make it funny all the way, really, really taxed my feeble little brain.

DAVIES: Well, you have a context of a story as opposed to a stand-up act,

where you're...

Mr. SEINFELD: There's no...

DAVIES: ...grabbing that audience and taking them where you want them to go.

Mr. SEINFELD: Yeah. Nobody seems to care that you're jumping to a different

subject every 90 seconds.

DAVIES: Right.

Mr. SEINFELD: That's why I prefer stand-up.

DAVIES: Now, I read that Steven Spielberg was kind of a sounding board here.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: What kind of advice did he give you?

Mr. SEINFELD: I'll tell you, he gave me some great advice, which I was

ashamed to have to receive. The hardest part of telling the story is coming

up with the end of the story, that make it--that it's satisfying. You know,

that after you've invested in these characters and kind of watched them go

through this journey, that you feel good about where it all wound up.

And at some point, I guess, we were three-quarters of the way through making

the thing, and I asked him to come in and look at it. And he watched it and

he said, `You know, the last quarter of the movie, what happened to the

silliness? What happened to all the fun and the silliness?' And I said,

`Well, I thought the ending should just be exciting and, you know, like the

hero comes to save the day.' He says, `No, not in this movie.' He says, `You

start off having all this fun and acting so goofy and silly, you have to

maintain that all the way to the end.' And, you know, as a comedian it was

pretty embarrassing to have to be told that by a guy who's really not known

for being that funny.

DAVIES: Right. `Jerry, you got to be funny here.'

Mr. SEINFELD: Yeah. `Jerry, you should be funny here in this part of it.'

So that was actually a great piece of advice that he gave us. It was like

that little--you know, you get close to something that you work on for a long

time and you can't see what's wrong with it. And that was like a big key,

that kind of, `Keep it silly.'

DAVIES: You know, it's interesting that when you do stand-up, I mean, nothing

is more autonomous than the stand-up comedian. It's his act and the feedback

is immediately.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm. Right.

DAVIES: I mean, you go in, you bomb, whatever. You kill.

Mr. SEINFELD: Maybe doing stand-up alone, by yourself, could be more

autonomous.

DAVIES: Possibly. And the feedback would be even more immediate. Right?

Mr. SEINFELD: Right. That's right.

DAVIES: But, you know, a movie takes years. It begins with endless meetings.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: There's endless editing.

Mr. SEINFELD: Yeah. Endless.

DAVIES: How did you adjust to the pace of it?

Mr. SEINFELD: I didn't adjust very well, to be honest with you. It kind of

goes against my natural instinct, which is, `I want to hear tonight if this is

any funny or not.' You have test screenings, and it was just like being

strapped down for four years. You know, I know a lot of other comedy writers

and comedians that would look at me and they would say, `You're still working

on that movie?'

DAVIES: Right.

Mr. SEINFELD: And I go, `Yeah, we're still going.' I mean, four years, it's

like I know people that wrote movies, got them produced, edited, released,

went on to other movies.

DAVIES: We're speaking with Jerry Seinfeld. He is the producer and star of

the new animated movie "Bee Movie."

Well, I want to talk a little bit about your stand-up, which has, you know,

been your core for years. And I thought--and I wanted to play a clip.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: And this is not you at a club. It's actually a clip from an

appearance on "Letterman," and I got it from the documentary that you did,

"Comedian."

Mr. SEINFELD: Uh-huh.

DAVIES: And the context here is you've--this is after the show has been off

the air for awhile and you're coming back, and it's a TV appearance. I don't

know if you remember this. Let's listen.

(Soundbite of "Comedian")

(Soundbite of audience clapping)

Mr. SEINFELD: Thank you. Thank you, I appreciate that. I totally

appreciate what you're saying. I do. But the question is this: What have I

been doing?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SEINFELD: Everybody says to me, `Hey, you don't do the show anymore.

What do you do?' I'll tell you what do I do: nothing.

(Soundbite of applause)

Mr. SEINFELD: Yeah, I know what you're thinking. `That sounds pretty good.'

You're thinking, `I might like to do nothing myself.'

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SEINFELD: Well, let me tell you, doing nothing is not as easy as it

looks. You have to be careful. Because the idea of doing anything, which

could easily lead to doing something, that would cut into your nothing, and

that would force me to have to drop everything.

(Soundbite of laughter and applause)

(End of soundbite)

DAVIES: And that's Jerry Seinfeld, our guest, from the appearance on David

Letterman show many years ago.

You know, you know what I love about that clip is that you got four or five

really good laughs out of--what?--one joke.

Mr. SEINFELD: It was nothing.

DAVIES: Hardly a joke.

Mr. SEINFELD: Yeah.

DAVIES: I mean, and it's all--it just--it shows all those years in clubs,

you've just got the pacing and the punch exactly where you want it.

Mr. SEINFELD: Thank you.

DAVIES: And I mean, I know you spent all those years--you made your first

appearance on "The Tonight Show" in 1981.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: And throughout the '80s you were building a reputation as a stand-up

at a time when a lot of--there are a lot of other comedians that are out there

that are maybe getting more attention by being outrageous or profane or kind

of using props or crazy characters. And I wonder, you know, kind of gave them

an identity and a hook.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: Did you ever try that stuff or were you ever tempted to try it?

Mr. SEINFELD: No, I never was. And I always felt like I was very much a

hookless comedian and I would always be hookless. And that, I thought, maybe

that's my hook, you know, that I just don't have anything that you latch onto

as, `He's the guy who does this or looks like this.' But it wouldn't have felt

right anyway. I mean, that was kind of the joke about the show, was that it

was about nothing.

DAVIES: Right.

Mr. SEINFELD: But what it really was about was the way we executed it. And

it's the same thing as what my stand-up is about. It's the same thing as what

that joke was about. What is that joke? It's taking the word "nothing,"

"something," "everything" and "anything" and assembling it into a thought that

makes sense. And so that's really what I like to do, is I'm more into the

execution than I am anything--other aspects of it. I mean, I don't even care

about being famous or being, you know--I just enjoy the doing of the thing.

DAVIES: Well, you know, in the documentary "Comedian," which is, you know,

for those of you haven't seen it, it's you going back to stand-up after having

done the show.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: Kind of getting back into it. And there's this moment in it that I

really love where you've sort of built the act up toward you've not got a good

50 minutes.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: And you do an appearance, I think, at a club in Washington, DC. And

it seems to have gone pretty well, but after it you're not satisfied.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: And you're saying, `God, it's just so hard to really feel

comfortable.' And you're kind of bemoaning whether you really hit it...

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: ...as you're packing your stuff and getting into your private jet--or

what looks like you private jet.

Mr. SEINFELD: Yeah.

DAVIES: And so what's fascinating is we have you, who have all that money and

success, that insist on subjecting yourself to this ego-battering process of

getting back in live clubs.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: You always want to do that. Why?

Mr. SEINFELD: You know, it's just that feeling of not cheating that is the,

I think, the best feeling in life. I didn't cheat at that. And stand-up is

the only thing I knew that I could be sure that I--if I was doing it and

audiences were responding well, that I wasn't cheating. Because there is no

way to cheating in stand-up. It's the nakedest, purest thing in the world.

But, you, you know, I could have gone into a movie. Someone would have said,

`We have a great idea for a movie for you.' And they could have put me in a

movie and promoted the movie, and the movie did this, and I would never know,

`Was that any good or not?'

DAVIES: Right.

Mr. SEINFELD: You know, `Well, the director didn't handle you right.' Or,

`It wasn't promoted the way it should have been.' There's always a million

excuses. There's no excuses in stand-up. So after all of that experience of

Hollywood and television and everything that the show did, I just wanted to

get back to something that I knew what was right and wrong, and what was black

and white. And it's a very black and white world, and that was calming to me,

and that would make me feel--I just never wanted to feel like I was skating on

a reputation or, you know.

DAVIES: And you can't skate on a reputation at a live club?

Mr. SEINFELD: No, absolutely not.

DAVIES: Even if you're Jerry Seinfeld?

Mr. SEINFELD: Even if you're Jerry Seinfeld. Maybe a couple of minutes.

The may give you three or four free minutes at the top, but after a while no

one laughs at a reputation. It's not funny.

DAVIES: And did you get where you wanted to be? Did you get comfortable?

Mr. SEINFELD: I did finally. It took about four or five years of working.

And I've lost it a little bit now doing the movie, and I'm going to go back.

But it's kind of a tennis game. A stand-up act is like a tennis game. I

mean, even if you're good, you've got to keep playing if you want to keep that

game at the certain point.

DAVIES: And you're sure you want to keep playing?

Mr. SEINFELD: Yeah. I love the simplicity of it. I love the purity of it.

It's just--this is what, I mean, all this work that we went in the movie, I

mean--to make an animated movie, the infrastructure of DreamWorks is a billion

dollars. That's what it costs just to have the machines to make one of these

things. And then the years of work. And what is it all for? Its so when we

put it in front of the audience, you hear a laugh.

DAVIES: Same thing as standing up and telling a joke, right?

Mr. SEINFELD: Same thing. Same thing. So, you know, I like--it's the

difference between, you know, you say you like the water, well, you can be the

captain of a ship or you can surf.

DAVIES: Right.

Mr. SEINFELD: And stand-up is like surfing, you're just right there. Right

there with it.

DAVIES: We're sticking with Jerry Seinfeld. He stars and produces a new

movie called "Bee Movie." We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

DAVIES: If you're just joining us, our guest is Jerry Seinfeld. He has

written, produced and stars in the new movie "Bee Movie."

Well, since you were last on FRESH AIR, you did this TV series, which kind of

took off.

Mr. SEINFELD: Right. Right.

DAVIES: And as sort of a measure of its cultural reach, my wife had a career

change this year and she had about six weeks between her old job and when she

began her new life as a resident in psychiatry, which was in June and July.

And I began referring to this time, which she had looked forward to so much,

as her "Summer of George." Which, for folks who may not recall, was the

"Seinfeld" episode where George Costanza has a summer off and he buys an easy

chair with a built in refrigerator.

Mr. SEINFELD: Right.

DAVIES: And what's funny about it is that, you know, when I kind of came up

with that phrase, everybody in my family laughed and talked about it. She

would talk about it to her friends. They all knew exactly what we were

talking about.

Mr. SEINFELD: Right.

DAVIES: And in a way, that series, which you haven't made a new episode in

nine years now, but it's all over television...

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: ...is sort of this book of life. I mean, people use moments and

lines from that series to describe what's going on in their lives. You're

aware of this phenomenon.

Mr. SEINFELD: I am, but I don't get it. I mean, it mystifies me as much as

you. And I'm only happy that it's doing something for somebody.

DAVIES: It doesn't mystify me because you're capturing stuff that we all kind

of recognize.

Mr. SEINFELD: Right. But doesn't--isn't every--why is it different with

other comedy shows? Why can't you name other comedy shows? You know, Larry

David said to me the other day that this was the first show where people would

say, `Well, that's a "Seinfeld" episode," about something that, `I had a day

today that sounds like a "Seinfeld" episode.' That our show was, for some

reason, lent people to think like that about their own lives. Because I guess

maybe one of the reasons is we stayed so close to people's real lives. We

tried to, anyway, as much as we could, aside from, you know, hitting golf

balls into the blowhole of a whale.

DAVIES: Right.

Mr. SEINFELD: And maybe that's why people can analogize to it or from it.

DAVIES: Well, you know, it's interesting because I read a piece about you

when you were doing stand-up, like maybe '89, when you were pitching the show

to NBC. And you had made quite a reputation in the stand-up act and were just

about to do a series. And there had been--the LA Times actually had a

full-time comedy writer who did a review of a show you did, and was pretty

critical.

Mr. SEINFELD: Lawrence Christian.

DAVIES: That's the one.

Mr. SEINFELD: Lawrence Christian, yeah.

DAVIES: And the criticism seemed to be, `Seinfeld, yeah, he's a pro. His

sets are funny but they're sort of not enough--what?--substance. There's not

enough of a message.'

Mr. SEINFELD: Yeah.

DAVIES: And how ironic that like now all these years later this is--it's your

stuff that kind of evokes the score of life.

Mr. SEINFELD: Right. Yeah. That guy didn't like me. The reason he didn't

like me--and I don't--I did not begrudge him for not liking me--is because I

had a publicist at the time that put a sign in front of the theater that

said--and I didn't know anything about this--it said, `Jerry Seinfeld, master

of observational comedy.' And that's like--well, the show ends right there.

You put that in front of your theater, no one is going to like you. You know,

it's like, `And now, ladies and gentlemen, please welcome the funniest man in

the world.' That's instant death to follow that.

DAVIES: I mean, don't people hype all kinds of stuff? I mean, the audience

loved the show, didn't they?

Mr. SEINFELD: Yes. As we said, my thing--it's a hookless act. It's a

humble act, hopefully, you know. It's really about little things that are

hopefully well observed. And so the guy, you know, so he just lit into me.

It was an interesting moment because, yeah, the series was just beginning and

then this horrible thing appears in the paper, and everybody thought, `Oh my

God, is NBC going to get cold feet now and they going to bail out on the

series?' But a lot of times, there's always this thing with, `Well, he's no

Richard Pryor,' you know? And I always, you know, would apologize for not

being raised by prostitutes in a whorehouse. There was just very little I

could do about it. I try to overcome it as best I can.

DAVIES: How did you know when it was time for the show to end?

Mr. SEINFELD: From my stage act. The stage act, you know, I had been doing

comedy, let's see, about 23 years at that time. And you start to know on

stage when to get off. There's just this feeling that you develop from years

and years of doing it. You just feel that we're getting--everyone's really

having a good time and I think in another few minutes this is going to start

to get old. `Good night, everybody.'

DAVIES: Hm.

Mr. SEINFELD: And everyone's happy. And I'm sure you've had the experience.

Everyone has had the experience of going to a movie that you love but for some

reason they just make it 15 minutes longer than it really needed to be. And

the change in your feeling about the movie because of that little 15

minutes--and it may not even be a bad 15 minutes. It's just proportions, you

know. I guess it's a function of art and economy that economy is essential to

all good art. And I thought, `Let's'--even thought we had done a lot, nine

years, 180 episodes, I thought, `We can't do one too many or it's going to

taint the whole thing.' So it was more the energy I felt around the show

itself.

DAVIES: That's what's interesting, because on stage you've got that--you said

that you have that sense from the audience...

Mr. SEINFELD: Right.

DAVIES: ...that you've honed over the years.

Mr. SEINFELD: Right. It was in the office. It was in the office of the

show. The writers would come in, and the way they would look at me and when

they would say, `So I had a thought that maybe Kramer would, you know, become

friends with a penguin or something.' You know? And I just, I would hear it

in their voice, `They're not as excited. This is getting old.' And I thought,

`Well, if it's happening here, the audience is next.'

DAVIES: Right.

Mr. SEINFELD: And, you know, I had a meeting with Jack Welch and he showed

me--it was a hilarious meeting where he...

DAVIES: It was with the chairman of...

Mr. SEINFELD: The chairman of GE at the time.

DAVIES: Right. Which owned NBC.

Mr. SEINFELD: And they owned NBC. And he had these charts of the ratings

and the demographics of the show. And every chart showed the numbers going

up. He said, `You have improved your audience from the eighth season to the

ninth. The ninth is stronger than the eighth.' So it was all backwards. You

know, usually you go in there, you try and tell them why you deserve more

money and why the show should be kept on.

DAVIES: Right.

Mr. SEINFELD: And it was the--everything was backwards. I'm telling him,

`No, no, no. We shouldn't go anymore.' He says, `No, no, no. You should.

I'll give you a raise. I'll give you more money.' You know, I said, `I don't

want money. I want the audience to have this thing.' It was kind of like--and

I don't mean to compare myself in any way, shape or form to the Beatles--but

when the Beatles ended, it was so sudden and it made what they did somehow

more valuable.

DAVIES: Right.

Mr. SEINFELD: Because it just suddenly was over, and that's it. That's the

complete set. You know, nine years, 12 albums, whatever it is, that's it. So

I kind of took from that, `I want to try and do that.'

DAVIES: You know, it's funny. I can't help but think of the episode in the

series when George Costanza adopts this posture and in a meeting gets the one

funny line--cracks off a line that breaks the room up.

Mr. SEINFELD: Right.

DAVIES: And he said, `That's it. I'm done. I'm out of here.'

Mr. SEINFELD: That's where the idea came from.

DAVIES: Yeah. Yeah.

You know, the series was about these four adults, single adults in New York,

living kind of very self-absorbed lives. You now have three kids, you have a

whole family life.

Mr. SEINFELD: Mm-hmm.

DAVIES: Are we going to see a whole new kind of material out of you?

Mr. SEINFELD: I do talk about my kids and my wife a lot more. I say this in

my act, `Because I don't talk with single guys. I'm not interested in them or

their lives. That if you don't have a wife, we really have nothing to talk

about.' And they say--most of the guys will say, `Well, I have a girlfriend.'

`OK, well, that's whiffle ball, my friend' You know, `You're playing paintball

war and I'm in Iraq with real guns.'

DAVIES: It's the real thing.

Mr. SEINFELD: Yeah.

DAVIES: Well, Jerry Seinfeld, I wish we had more time, but thanks so much for

speaking with us.

Mr. SEINFELD: Thank you. It was my pleasure.

DAVIES: Jerry Seinfeld is writer, producer and co-star with Renee Zellweger

of the new animated feature "Bee Movie.' I'm Dave Davies, and this is FRESH

AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Journalist James Fallows talks about Chinese factories

and the industrialization going on in China

DAVE DAVIES, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies filling in for Terry Gross.

My guest, James Fallows, made a startling observation in a recent piece in The

Atlantic Monthly. According to his estimate, there are more manufacturing

jobs in the southern China province of Guangdong than in the entire United

States. Fallows is living in China these days, and he's written about the

enormous scale, unique methods and widespread impact of China's fast-paced

industrial revolution. James Fallows is national correspondent for The

Atlantic Monthly. He's written seven books, his most recent is "Blind into

Baghdad: America's War in Iraq." I spoke to him last week about his reporting

from the industrial city of Shenzhen in southern China where hundreds of

factories are located.

Well, James Fallows, welcome back to FRESH AIR. Describe a factory, one of

these outside of Shenzhen that you've visited.

Mr. JAMES FALLOWS: Well, I'll describe one that I couldn't get into because

there's like a military camp. The biggest one in that whole area, and

probably the biggest factory complex on earth, that the earth has ever seen,

is a company called Foxconn, that's their English name. They have an office

in Shenzhen. They are owned by a Taiwanese entrepreneur who's operated in

southern China for a while. And in this one plant, something like 250,000

people go to work every single day. They live there, they eat there. They

have this giant encampment. In scale, it reminded me most of, say, Los

Angeles International Airport. That's about how big it was to drive around

the periphery. The statistic I like best about this factory for Foxconn is

that, simply to feed its own work force, the caterers have to kill 3,000 pigs

every single day. You know, Chinese pigs are not that big, but still it's a

lot of pork going in there.

The more typical factory, of which there are thousands, probably, in just the

Shenzhen area, these are factories that often produce electronics, shoes, you

know, light manufactured goods, a lot of hand labor. And the typical employee

will be a young woman, maybe in her early or mid 20s, who's grown up in some

other part of China, in the provinces, in Sichuan province or some other rural

area, and her family's income would have been about $100 a year in cash back

on the farm. And once she goes to this factory in Shenzhen or neighboring

city, she can make about $100 a month or $130 a month. And in the course of

several years of this full-time factory work, living in the factory, eating in

the factory, she can save essentially a lifetime savings. And so many of

these people then either--some of them stay in the city, but some of them,

after three or four years, go back. And so you see these seas of young women,

all at the assembly, in some cases--heavy industry--young men. And it's like

in a sense a wartime effort. They spend 24 hours a day essentially in the

factory complex, and for them it's a good economic deal.

DAVIES: And so in these light manufacturing plants all throughout Shenzhen,

are most of the employees women?

Mr. FALLOWS: It does seem to go by the kinds of things they are making. For

example, I've seen some big places where they're making air conditioners, and

most of the people there were men. But if you think of the classic `made in

China' good, for example, any headsets that people might be using to to listen

to this show right now--or actually, in fact, any audio equipment of any sort

by which people are listening to this show whether it's on a webcast or over

the radio, that most likely came from a factory in China. And factories like

those, it is predominantly young women. And in those factories you see a kind

of hand labor that is simply not efficient to do in the Western world anymore

because, you know, if you are paying people to snap things together, one every

five seconds, 10 or 12 hours a day, the wage rates would be prohibitive in the

US.

DAVIES: Now, where do the employees live and eat?

Mr. FALLOWS: There are, in the typical factory, and I'm thinking of one now

owned by a company that I won't name--well, the company I won't name because I

can't actually remember its name is one of many anonymous small Chinese-owned

manufacturers, but they would do contract work for almost any brand name you

can think of in the US. You know, whether it's, you know, name a brand name

and that company almost certainly has its manufacturing done in China. The

employees there will work on the assembly line for eight, 10, 12 hours a day,

depending on the work flow, and live in a dormitory.

And the dormitories range from pretty gruesome, of maybe 10 or 12 people or 14

people living in one small room and having essentially for themselves just a

bunk area to nicer than that of having two or three people per room. They're,

you know, they're not--by Chinese standards they are tough but not abusive.

And they will eat in company cafeterias. You know, they're free to eat other

places, but three meals a day are basically part of the standard employment

package in addition to the cash. So if these young women are looking to save

up money to send back to their families or save themselves, they will live

just in the dormitory, eat just in the company canteens, and that is their

life for the several years.

DAVIES: You made a point in the piece that, while some would regard these

conditions as abusive or even equivalent to slavery, if you look at it, you

believe that folks living this life are perhaps even better off than someone

attempting to live on a minimum wage, say, in Chicago.

Mr. FALLOWS: And let me stipulate, there are a lot of really abusive and

terrible factories in China. And almost every day you'll see an item in the

paper of somebody who, you know, 10 people blown up in a steel mill or, you

know, there was a horrible story of something like 36 or 37 people who were

covered with molten steel in a steel plant in one day, and of course all died.

So there are many factories that are dangerous, rough. You know, there were

reports of sort of slave labor factories north of China recently. But the

average factory, at least the ones I've seen, is not that way. They're

instead quite tough and demanding.

But from the Chinese perspective, this has been, not 100 percent, you know,

success, but a huge success for the country in the following sense. That in,

if you think of India, the people in India who've been able to interact with

the world economy and make their way up in the world are people who already

have been educated and know enough English and enough sort of sophisticated

information to work in a call center or to be part of some kind of software

support, and that's a number in the single digits of millions of people in

India who are able to that.

In China it's many tens of millions of the rural peasants who have been able

to have a tenfold increase in their cash income by going to the factories.

And the contrast with somebody on minimum wage in the US, that a person--it is

almost impossible for somebody on the minimum wage in the US to move ahead.

You know, saving, it is--you can imagine scenarios in which people could save

money and feel as if they could have a better future if they're on minimum

wage in the US. But anybody working in a factory in China knows that his or

her future is much, much brighter than their family would have been and their

future would have been if they were still in the countryside or in the past

generations of Chinese, uneducated people, have enjoyed. So in these

factories, of course there are complaints, of course there are searches for a

better situation, of course there are things that need to be fixed. But the

average sentiment in the factories, as I was able to find out about it, seemed

to be that this was an opportunity from their point of view because they were

having the equipment for a better life.

DAVIES: If you're just joining us, we're speaking with journalist James

Fallows. He is living in China and studying industrialization there and

writing for The Atlantic.

You know, China is still a one-party state and, at least in theory, a

socialist country. Who owns all of these scores of factories in the Shenzhen

area?

Mr. FALLOWS: You know, the relation--what exactly socialism and communism

mean in China now is a very rich topic, and you could argue that communist

China is less a welfare state than the United States is or any part of Europe

because there's no retirement program, no health insurance program for most

people. The actual ownership of the means of production in the most

productive parts of China is mainly through small businesspeople, often

Taiwanese. And the typical factory in Southern China where the goods

Americans buy every day come from, it would be probably a family-owned

enterprise, more likely than not a family that has some ties to Taiwan and

that have come across the straits to southern China to operate, or some small

business from the area. But they're small enterprises in really cutthroat

competition with each other to take this next half percent out of their

bidding price to Dell or Hewlett-Packard or Sony or whoever they're doing the

contract work for. So it's a more classic and really every single day

competitive model of small scale capitalism than we see in a lot of America

now.

DAVIES: And so what we have in this area, this province north of Hong Kong,

are hundreds and hundreds of small manufacturers, and a kind of a frenetic

competition, really, to supply international companies with parts and

components of all kinds of things, a lot of them electronics, right?

Mr. FALLOWS: Exactly.

DAVIES: And one of the points you make is that a Chinese company could

respond very quickly to the need of an American manufacturer to bring on a new

product line or to make a change in a component part. Why are these Chinese

factories--which, you know, are so labor intensive--able to deliver so quickly

and so cheaply to these American or, well, these international needs?

Mr. FALLOWS: I spend a lot of time in my reporting and in my article talking

about a man named Liam Casey, who's of the sort of central figures in the

whole outsourcing business. He exists to put Western-branded companies in

touch with Chinese manufacturing firms that can do their actual production

work for them, either firms as large, let's say, Apple, or firms as small as

some start-up that has an idea and needs to get it produced to bring it to the

American market.

And a point that Liam Casey made to me again and again and again is that

people think the Chinese manufacturing advantage is just that things are

cheap. And, of course, they are cheap. And if you have people making $100 a

month, that's quite different from the US labor cost. But he said that even

more than that, the profound advantage the Chinese manufacturing had now was

that it was so fast and flexible and responsive and adaptable because all

parts of the production machine were there in one place. If you needed to

have a small piece of leather, you know, tooled in some way, you know, one

inch by four inches with a certain number of perforations, there were five

companies that could have these samples tomorrow afternoon. And if you're

working in Dusseldorf or you're working in New York, you know, maybe you'd

have one supplier maybe that could do something next month.

So it's this whole ramified network of all the different parts of the modern

manufacturing experience which now are more and more concentrated in China,

and particularly this part of southern China. And the companies--the firms

that do the connections between the Western customers and the Chinese

producers, they're specialty is knowing how to put these pieces together

saying, `you want this piece of plastic in red of just this dimension, here

are the five companies that can bid on it and I'll have them all for you to

see tomorrow and we'll see who gets the business.'

DAVIES: And this gentleman that you mentioned, who you describe as Mr.

China, he's made kind of a life of--I think you said that he has actual GPS

coordinates for all kinds of Chinese manufacturing locations, not stuff you

can get in any directory or in any government registry, right? It's a matter

of knowing the terrain?

Mr. FALLOWS: Exactly. And part of it, the problem is that maps literally

are out of date the instant they appear because roads are being both built and

destroyed so rapidly in China, and new factories and new buildings, and so

knowing simply where things are is a big competitive advantage.

Mr. FALLOWS: Our guest is James Fallows. He's living in China and reporting

on his experiences there for The Atlantic. We'll talk more after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

DAVIES: If you're just joining us, we're speaking with journalist James

Fallows. He writes for The Atlantic. He is living in China now and has been

writing about industrialization there.

You say in the piece that 90 percent of the laptop and notebook computers sold

in the world under all these famous brand names come from Chinese companies in

this part of southern China, is that right?

Mr. FALLOWS: Yes, it is. And it doesn't matter the--you can name any brand

of notebook computer, whether it's a Thinkpad, whether from Lenovo or IBM or a

Sony or an HP or a Dell, or you go down the list, and it is almost certain

that it comes from one of five no-name Taiwanese companies that have these

factories in China, some around Shanghai, some in southern China, they do the

actual production of almost all the notebook and laptop computers in the

world.

DAVIES: One of the interesting sections of your piece in The Atlantic

detailed how an online order would come in for Liam Casey's company and

exactly how quickly the factory would respond and get it out. If you could

just kind of run that down for us.

Mr. FALLOWS: I enjoyed very much seeing this place. So I'll tell you the

process, and once again, I can't tell you the name of the American brand this

is sold under, although I guarantee that every single person who listens to

this knows the name of this American-based consumer electronics company. So

this company has a Web site, and on the Web site people can order devices,

they can order accessories, they can order all kinds of stuff like any other

Web site you go to for a major American brand product. There's a 12-hour time

difference between the US East Coast and China time. So the factory in China

works sort of on reverse from American time.

And while I was there in the wee hours of the morning China time, which was

late afternoon in America, I saw a person, a man, in fact, from Palatine,

Illinois, who was browsing around on the Web site, you know, for this American

manufacturer and saw something he wanted and clicked on the "buy now" button.

And within a few seconds, you know, 10,000 miles away in Shenzhen, the order

form was printed out complete with a bar code. And the bar code specified all

the details. So on the other end of the Internet this order comes out and a

series of young Chinese women took it. The first one scanned it in then it

produced the address label that would be used for this man and it also had the

packing box. The next person on down started putting in the main thing this

person had ordered.

The next one on down checked the bar code and had a so-called `pick two light'

process. There was a big, essentially a wall sized array of little tiny

cubbyholes like a sort of a post office box array. And whatever item had been

called for by the bar code specs, the light would go on over that thing. And

so the young woman would pick off that accessory, she would run its bar code

across a scanner like in a grocery store, put it into the box. At that point

there would be a very, very sensitive scale which would say, OK, we know these

three components are supposed to be in here, does the weight in grams equal

exactly what we think it should be? It would go then to the next person who

would re-scan the things to make sure they were fine and somebody else to pack

it up.

And then, the interesting part to me, is they were put into these shipping

boxes and then assembled on big shipping pallets, you know, maybe a cube

essentially five feet in all dimensions. And these were for the shipping

company, either FedEx or DHL or UPS to pick up, you know, a few hours later.

And when the shippers' deadline came, pick up time, let's say it's 9 AM China

time, 9 PM US East Coast time, suddenly all activity in the factory in China

was focused on this moment. The shippers would come in, they take off these

pallets and they'd rush them to Hong Kong airport. On the flights to

Anchorage there'd be some preliminary sorting, you know, which ones to the

East Coast, which ones to the West Coast and they'd all be arrayed. And

within 36 hours of the time the customer in Illinois clicked on the "buy now"

button, you know, triggering this event, the package would show up at his or

her door, you know, via FedEx.

DAVIES: It's fascinating to read these descriptions of these factories and

kind of the level of competition and how integrated they are into

international markets. But let's look at, evaluate it a bit, is this good for

China? How do you read it?

Mr. FALLOWS: From the Chinese perspective, I would have to say, as I think

most Chinese people feel, this is overwhelmingly good from a Chinese

perspective. Here are the bad parts. One bad part from the Chinese

perspective is the US has effectively outsourced a fair amount of pollution to

China. You know, as factories have gone, so have factory smokestacks and all

the rest. And the pollution in China is unbelievably horrible. It's the

single greatest threat that country faces and I think the world faces because

of China's industrialization. So that is one cost they absorb.

A second cost they absorb is there is some downside to factory life where

young men and women are spending three or four years, you know, just

essentially on full-time labor detail. This is hard on them. It's hard on

their families. It has all kinds of, you know, there are social side effects

of alienation, drug use, crime and all the rest that have been part of

industrialization through history. That is a problem. And there are, you

know, the side effects of kind of uncontrolled growth. Those are the things

which would be problems from the Chinese point of view.

On the other hand, you do now have tens of millions of people--perhaps, you

know, 100 million people or more, who have, thanks to the factory life, have

been able to make the leap from really hand-to-mouth existence on the farm to

having enough cash that they can have other choices. They can pay for their

children to go to school. They can set up little businesses. They can get

married. And so I think the Chinese view their factory life as being the

great success story of the last generation.

DAVIES: Our guest is James Fallows. He is living in China these days, and

writing about his experiences for The Atlantic. We'll talk more after a

break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Announcements)

DAVIES: If you're just joining us, we're speaking with journalist James

Fallows. He has been living in China, where he is writing about that

country's efforts at industrialization for The Atlantic.

One of the questions that comes to mind as you look at the industrialization

in China is whether a one-party state can continue to rule over our country,

which becomes more urban, and more and more a part of a capitalist, monetary

economy. I mean, do you see signs of, you know, what is in effect a kind of a

backward and corrupt political structure straining against or struggling with

the needs of capitalists to do what they need to do?

Mr. FALLOWS: You know, this is a fascinating and rich question, which people

in China, especially outsiders, the number of Chinese, too, debate every

single day. And I think nobody has any confidence on what--in predicting what

will happen in the long run. My observation of the tension between the

political system and the economic system is a little different from what I

think the normal outside American observation would be. You know, we usually

think as a country prospers, it has to become more democratic or else it will

be cut off. I think the limit on China is slightly different from that.

You know, China, as I've been saying, at the moment is very, very strong in

quite low wage manufacturing jobs. The question--you know, their hope,

America's apprehension--is whether they can move to take the higher level

positions too. And it's observed around the world that those higher level

positions, you know, having fundamental new inventions, having really good

industrial designers, having real product innovations, so you're not just

making an existing product cheaper but you're coming up with a truly new one,

those are associated with democratic societies.

But even more I think they're associated with another set of trade. They're

associated with very strong universities where you can have independent

research. China's universities are quite weak. You know, they're not good in

independent research at all. They're associated with intellectual property

protection so that people can make money from their inventions. China's

intellectual property protection is ridiculously weak. You know, everything

is up for grabs from everybody. They're associated with rule of law and

sanctity of contract. And if you make a deal, you'll have a deal, which is

generally not the case in China. They're associated with a kind of ethic of

trust so that people can operate without everything having to be written down.

And there's quite a pronounced lack of trust in China, which is why firms are

typically so small. They don't trust, you know, what people who are not in

their families to operate.

And so I am persuaded of the argument that for China to really take the next

step in prosperity, it needs to have a lot of these other cultural conditions:

better universities, a more sort of trustworthy legal system, better copyright

laws and all the rest. The question is, does that mean a democratic political

system, too? I think for China to really prosper in a profound way, it would

need to be a more--it would need to be more a society of civil liberties and a

more society of kind of independent inquiry and independent voices. Whether

that means actual political competition for power and having some other party

besides the Communist in the mix, I just don't know. And I think the

calculation of the current leadership is they think they can stick with this

model for a while.

DAVIES: Do you see signs that workers in Chinese factories are restive, that

they feel exploited and maybe want to organize unions or seek to redress

grievances from the government or their owners?

Mr. FALLOWS: This is one of many places where I should say that, you know,

anybody who presumes to say what's happening in quote "China" unquote is nuts

because it's so big and so diverse. So I can talk about what I've seen in a

lot of factories in one part of China. My impression is that, you know, the

workers there are by no means docile, and by no means just satisfied with

whatever happens. And one reason why at a lot of work sites mobile phones are

outlawed is that Chinese people love mobile phones. Almost everybody has

them, even peasants. And they send text messages around the clock. And in

the factories, they'll often be sending text messages saying, `hey, we can

get, you know, two RMB a day more this other factory, come to this other

factory.' So mobile phones are a way of complaining about conditions and

seeking out better options. And there is considerable activity among Chinese

workers.

In the factories I saw, however, there was neither some sense of sullen

oppression and people just looking to rise up against the man and overthrow

them and, you know, lash out against their hated oppressors. More it was

people who were working very, very hard to get their money. Nor were unions

really the answer because in China unions are essentially another branch of

the state. China's the only part of the world where Wal-Mart is unionized.

And they had to be, you know, to operate there. And essentially the unions

work as part of the Communist Party structure so they're not really a way to

exercise leverage for what we think of as real workers' rights.

DAVIES: How much has Chinese manufacturing been damaged by these scandals

over, you know, food contamination? There was dog food, toothpaste.

Mr. FALLOWS: I think that the Chinese--there is a clear sense in China that

the so-called China brand has been very, very seriously hurt by all the

legitimate problems they've had. And by "legitimate" I mean real problems,

not just a perception of unsafe Chinese products but a reality of that. The

reaction in the Chinese press has been interesting to me in that the minor

theme has been, `oh, the foreigners are blaming us, they're picking on us, you

know, they have their own bad products, too, it's not just us.' The major

theme has been, `this is a problem for us, we need to clean it up. What are

the ways we can redress it?' So they recognize on the one hand that when

consumers have options in the Western world they may steer away from Chinese

vegetables or Chinese processed food or Chinese toothpaste. And the people in

China don't have that much choice.

But there are a whole lot of things in which, for Western consumers, the

Chinese component is either not obvious or it's not avoidable. You know, if

you wanted to buy a non-Chinese-made computer, well, good luck. You know,

you're not going to find one. So I think they recognize this is, like

pollution, a genuine problem, and dealing with it is another issue.

DAVIES: Well, James Fallows, thanks so much for speaking with us.

Mr. FALLOWS: It's been a pleasure. Thank you.

DAVIES: James Fallows is national correspondent for The Atlantic Monthly.

You can download podcasts of the show at freshair.npr.org.

(Credits)

DAVIES: For Terry Gross, I'm Dave Davies.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.