Contributor

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on February 23, 2000

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: FEBRUARY 23, 2000

Time: 12:00

Tran: 022301np.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Attorneys Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld Putting the Justice System on Trial

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:06

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: From WHYY in Philadelphia, I'm Terry Gross with FRESH AIR.

On today's FRESH AIR, using DNA evidence to free the wrongly convicted. We talk with lawyers Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld about their group, the Innocence Project. Scheck is best known for his work as the DNA expert on the O.J. Simpson defense team.

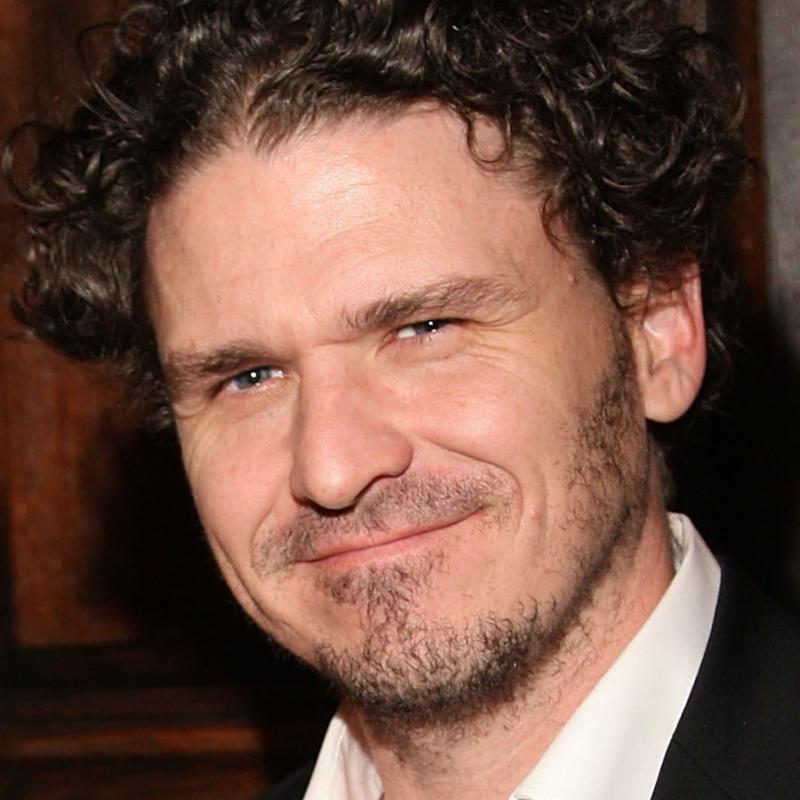

Also, Dave Eggers talks with us about his new memoir, "A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius," about raising his 8-year-old brother after their parents died. Eggers co-founded the publications "Might" and "McSweeney's."

And jazz critic Kevin Whitehead reviews a new boxed set of Django Reinhardt recordings from 1936 to '48.

That's all coming up on FRESH AIR.

First, the news.

(NEWS BREAK)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

DNA evidence is changing criminal law. It's not only helping to convict murderers and rapists, it is also helping to exonerate the wrongly convicted, people who were on trial before the widespread use of DNA testing.

My guests, Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld, founded the Innocence Project, which uses DNA evidence to establish the innocence of prisoners who were wrongly convicted. You probably remember Scheck as the DNA expert on O.J. Simpson's defense team.

DNA evidence has helped gain the release of nearly 70 wrongly convicted people. The Innocence Project has worked on 37 of those cases. The project is based at the Benjamin N. Cardozo Law School, where Scheck and Neufeld teach. Both have private law practices in New York.

They've co-authored a new book with "New York Daily News" columnist Jim Dwyer called "Actual Innocence." Scheck and Neufeld met while they were working as Legal Aid lawyers in the South Bronx.

Here's Peter Neufeld.

PETER NEUFELD, THE INNOCENCE PROJECT: For all of us who toil in the criminal justice system, prosecution, defense attorneys alike, one of the scariest kinds of cases to take on is a case that relies exclusively on a one-witness identification, because we have an intuitive sense that eyewitnesses can often be wrong.

With the arrival of DNA typing, we realized, here was a test that could determine whether or not the eyewitness was correct or not correct, at least in sexual assault cases. And so that's where we thought its greatest application would be. And frankly, of the 69 exonerations that are discussed in the book, or referred to in the book, almost all of them involved either sexual assaults or sexual assault-murders.

GROSS: Give us the basics of the science of how DNA testing works, just the basics that we need to know to understand it.

BARRY SCHECK, THE INNOCENCE PROJECT: Well, it's a simple process. One can look at semen, as Peter mentioned, skin cells, hair, bone, any kind of biological material that has DNA in it, and basically just take that material and extract the DNA, and match the DNA pattern for certain genes or markers of interest against the suspect or the victim or whomever else it's relevant to test.

GROSS: What are the advantages of DNA testing over, say, blood testing or hair samples?

NEUFELD: Well, one of the great things that we uncovered in this book with respect to hair samples is that for years, laboratories had been relying on comparing a hair found at a crime scene with a suspect's hair by using a microscope for examination. In almost, I think, 20 to 25 percent of the cases that are examined in this book where people were unjustly convicted, the prosecution relied on this hair microscopic analysis to help convict somebody, only to realize, after we did the DNA testing, that they were wrong.

So obviously the DNA testing shows quite clearly that certain types of forensic testing which have been relied on traditionally by crime laboratories and prosecutors all over the country, indeed all over the world, turned out not to be so reliable after all.

GROSS: After overturning the verdicts of wrongly convicted people, I'm wondering what conviction techniques you found to be most unreliable.

SCHECK: Well, the way the book is organized is that we try to tell these stories and focus each time on a different cause of wrongful conviction so you apprehend it through the stories. So mistaken eyewitness identification, single greatest cause everybody's known of the conviction of the innocent. And yet there are simple reforms which the Justice Department has issued in a pamphlet which, if adopted across the country by police departments, could minimize mistakes.

Then there's false confessions, which accounts for the conviction of innocent people on occasion. And if you just videotaped interrogation, the way they do in Alaska and Minnesota, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, that would help. So there's jail house informants. There's junk forensic science that we've discussed already, fraudulent forensic science. There's frankly, and most importantly, underfunded and incompetent defense lawyers.

It's really a terrifying situation to be a poor person and innocent in America and brought to trial, or middle class. If you don't have a good lawyer, you're in trouble.

There's prosecutorial and police misconduct, no question about it, a lot of exculpatory evidence that never sees the light of day. You know, these are the traditional causes of wrongful convictions. But there's a lot we can do about it, and we lay that out in the book.

NEUFELD: You know, but one other cause, which is sort of overlaid throughout all of these causes, is the question of race. One of the most disturbing statistics that we, you know, came up with by looking at these 63 exonerations in the United States is that if you're black, and you're accused of committing a sexual assault against a white women, the potential for an unjust conviction goes up astronomically.

For instance, the -- I mean, the Department of Justice says that about 10 percent of all rapes that are reported in this country are interracial. In other words, most of the time, you know, despite what Eldridge Cleaver wrote about 30 years ago, most sexual assaults are black men committed against black women and white men against white women.

And only about 10 percent of the sexual assaults are cross-racial. Nevertheless, about 45 percent of these unjust conviction cases that we have involved black men convicted of raping white women.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guests are lawyers Peter Scheck and Barry Neufeld, and they founded the Innocence Project, which works for the release of wrongly convicted people. They've also collaborated with journalist Jim Dwyer on the new book "Actual Innocence."

DNA can be used both for the defense and for the prosecution. Do you think it's giving either side the edge right now in the courtrooms?

NEUFELD: I don't think DNA gives anybody an edge. It's simply a, you know, an establisher of truth. There are many defense attorneys who are doing DNA testing routinely pretrial to clear somebody who may be falsely accused. It's a win-win for everybody. It means it's less likely that innocent people will be convicted, and it's also less likely that guilty people will get off.

SCHECK: We're strong believers in the technology, but people would probably be surprised to know, and we -- although we talk about it in the book, is that Peter and I are commissioners of forensic science in the state of New York. We're part of this group that regulates the crime labs, that sets standards for people collecting the evidence. We help train the police, we work with them on this, because it's very important that this technique is handled correctly so that we can exonerate innocent suspects and catch guilty people.

DNA gives us an opportunity to learn something about the criminal justice system. It's never happened in the history of this country, Terry, where so many people have been exonerated in so many cases so quickly. And nobody doubts that these are innocent people. There -- it's been proven to a scientific certainty.

So now we can go back and look at these cases and really make a good assessment of the system, what the strengths are, what the weaknesses are, what went wrong.

GROSS: My guests are lawyers Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld, and along with journalist Jim Dwyer, they wrote the new book "Actual Innocence."

I think most Americans are most familiar with DNA testing and its use in the courtroom through the O.J. Simpson case. And Barry Scheck, you were the DNA expert with the defense. And you argued against the DNA evidence that showed O.J.'s DNA matched the DNA in blood on socks, the fence outside Nicole Simpson's house, in O.J. Simpson's Bronco. And, I mean, your argument was that the people collecting the samples were incompetent.

Were you concerned at all that you would be arguing against the technique that you were trying to establish as really legitimate?

SCHECK: Well, actually we didn't. That was one of the only silver linings that I can see in the O.J. Simpson case for the criminal justice system, and people in the forensic community agree. We never argued that DNA testing was unreliable.

What we pointed out, and quite correctly, is that the evidence samples were woefully mishandled, and that, you know, you're not supposed to take wet samples and put it in plastic bags, you're supposed to change your gloves in between the collection of these samples. If you're going to do DNA testing, you're not supposed to bring it back to the evidence room and open up a suspect's blood sample and have it spray out over the table.

So what happened after the O.J. Simpson case is that all across the country, crime labs began attempting to get accredited. Manuals were written. If you go today, you'll see that the federal government now hands out a pamphlet called "What Every Law Enforcement Officer Should Know About DNA Testing." And it talks about -- it is virtually the cross-examination of the evidence handlers in the O.J. Simpson case. Change your gloves, don't put things in plastic bags, and on and on it goes.

And we've had a very good response from the forensic community because people understood that the arguments we were making in the case about the bad techniques were correct.

GROSS: Peter Neufeld, I'm wondering what you think about this, and if you think that the O.J. Simpson case set a precedent in how lawyers can argue against DNA evidence.

NEUFELD: No, it doesn't do that at all. You know, one of the things that we've all noticed from being involved in high-profile cases is how all too frequently legal commentators misunderstand what's happening in the courtroom and then misstate it to the listeners for their television and radio stations.

But the people in the know -- and that's what Barry's trying to point out -- the people who actually work in the criminal justice system, the police departments, the prosecutors, the people who are the scientists and run the laboratories, they saw what was going on, and they realized that it wasn't an attack on DNA science, it was simply an attack on the inadequate methods used by crime laboratories all over the country.

One of the things that Barry and I have been advocating since the very beginning is that crime laboratories be treated much more like clinical laboratories. If you have a growth on your arm and you want to have it biopsied, you want to have confidence in that laboratory that's going to make a determination which may cause you to amputate your arm or take certain medications, or not to.

Well, likewise, if these tests are going to be utilized to decide who dies in the electric chair and who lives, they'd better be just as rigorously controlled, both in terms of quality and in terms of the people who are doing the tests.

So we've been major advocates for that, and as a result of our work in New York now, for instance, all the laboratories here, with police departments and counties in the state, are regulated and are accredited. California's moving in that direction now, states all over the country will hopefully follow this lead.

Once they do that, everybody wins. There'll be fewer unjustly convicted people, and victims will be much happier because it means it's much more likely that the guilty person won't get off because of a screwup in the laboratory.

GROSS: My guests are Peter Neufeld and Barry Scheck. They've collaborated on the new book "Actual Innocence." We'll talk more after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

GROSS: My guests are lawyers Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld, founders of the Innocence Project, which uses DNA evidence to work for the release of the wrongly convicted.

I asked Barry Scheck when DNA evidence is typically collected in a criminal case.

SCHECK: The way it works in New York and most states in the country is that convicted individuals, usually convicted felons or people convicted of violent crimes, their DNA samples are taken from them, and they're -- you know, we extract the DNA profile and put it in a computer, so that when new crimes are committed, one can compare it to the DNA samples that are in the data bank. And in addition, and this is not being done nearly enough, we have to go back and look at old unsolved cases.

You know, the Innocence Project is one form of looking at old cases, where individuals are claiming, Look, I was wrongfully convicted, let's do a DNA test to prove my innocence. Equally, we went to the police commissioner -- I went to the police commissioner in the city of New York and said, Look, you've got 12,000 untyped, unsolved rape cases sitting in the medical examiner's office. If we just type those samples, we're going to find serial rapists and serial murderers.

And so he's gone out now and contracted with a private lab to go do that. So, you know, that's the way you should be using DNA data banks and DNA technology to both exonerate wrongfully accused suspects, wrongfully convicted people, and to catch the guilty.

GROSS: Any concerns about the impact of DNA data banks on privacy and civil liberties?

NEUFELD: Well, I mean, there are, of course, some major concerns in that regard, and that's why it's very important, number one, they only take samples from those people where there's a real nexus between the crimes they've committed and the likelihood that a DNA test will be able to catch them in the future.

This country has to be very concerned about using someone's DNA for other purposes. The eugenics movement did not start in Germany, it started here, and it was imported to Germany. There have been -- there's a whole history in this country of discriminating against people based on their genes. It's fine to collect material from convicted felons. There's a real reason to believe that you can, you know, use it in the future to capture them again if they go out and commit additional crimes.

On the other hand, if you have a national database where every man, woman, and child is included in it, there's also a real danger that that data will be used to investigate propensities for violence, antisocial behavior, and then you'll have people who might be selectively singled out based on race, ethnic group, or for other reasons, and dealt with unfairly by the country.

So it's not an all-or-nothing proposition. You have to use it, it has a very compelling use, but you have to restrict its application.

GROSS: A lot of criminals know to wear gloves so that they don't leave fingerprints, or they know to wipe the things they've touched so that they don't leave fingerprints. Do you think more and more criminals will become aware of DNA evidence and do things like trying to douche rape victims, or, you know, making sure they -- try to get rid of any blood or semen beforehand so that it can't be used to implicate them?

NEUFELD: Well, you know, it's funny, I mean, obviously the simplest way, if you were a rapist, to avoid detection would be to wear a condom. And what's extraordinary is, is that you'd think as a result of the DNA revolution, there would be a lot more rapes reported where the perpetrator used a condom. Doesn't seem to be the case. At least anecdotally, what we hear from prosecutors and police commissioners across the country, is that there's real no change in that, and that may have something to do with the psychological aspects of the crime itself.

SCHECK: There's also other materials that can be tested, Terry. We now can test the shaft of a hair with DNA, so that could be left at the scene inadvertently. I mean, of course, you know, anybody can try to cover up a crime and do that. But, you know, it's still a great investigative tool.

GROSS: I know that you felt that part of what you put on trial in the O.J. Simpson case was the procedures that were used to collect the DNA evidence, and you found those procedures...

SCHECK: It's not just what we felt...

GROSS: ... really, really wanting.

SCHECK: ... it's...

GROSS: Right. But, I mean, that was, I think, your mail role in the...

SCHECK: That's correct.

GROSS: ... case, is to challenge the collection techniques. But I think what a lot of people are wondering is, does that mean that you think O.J. Simpson was actually innocent, or does it just mean that you think the samples were mismanaged?

SCHECK: Well, are you asking me, Do I think O.J. Simpson is innocent or guilty of a crime? Well, he never told us, he's never said that he committed these crimes. He's always denied it. We're his lawyers, you know, there's a duty of loyalty here. I think the only thing you can say as a lawyer -- I mean, you weren't there -- is that given the evidence that the criminal jury had, I think that they reached a reasonable verdict based on the evidence they had before them, and in turn, given the standards of proof and the evidence that was before the civil jury, that verdict was reasonable.

More than that, a lawyer really can't say.

GROSS: One last question. Do you think that DNA evidence is changing the way defense lawyers and prosecutors are arguing cases where there is DNA evidence? Is it changing the style of, of, of, of courtroom techniques?

NEUFELD: No, what it's doing is -- and it's an unprecedented opportunity -- is that it's allowing us to get a better vision of how the system really works. That's what's the significance of these 69 post-conviction DNA exonerations. It's an unprecedented event. It's never happened in the history of American criminal justice or any system, and it gives us a chance to study what went wrong.

Think about this, Terry, that whenever an airplane falls from the sky, or a car blows up, or there's an unexpected death in a hospital, what happens? Well, my God, there's total system failure. So you have the National Transportation Board come in, there's a huge post mortem, people try to figure out, is it system error, is it individual error, is somebody at fault?

And most importantly, what can we do to change the system to fix it, to prevent these kinds of things from happening again?

The only system that doesn't do this, unfortunately, is the criminal justice system. When these people walked out of the jail cells and the courtrooms vindicated by DNA tests, you can't find in almost all of these cases a court opinion that says, This is what happened. It's just, you know, a few press articles. The conviction is vacated.

What we don't do, and we should do, and frankly, the governor of Illinois should be lauded for this, because when he saw that 13 people had been exonerated on the grounds of innocence off death row in Illinois, versus 12 executed, he said, Wait a second, we have to investigate this. So he appointed a commission to look into it, in addition to calling for a moratorium on executions.

We should be doing it even beyond the death penalty. Every state in this country ought to have a kind of innocence commission where we make an assessment of how it is when we have a case where somebody was wrongfully convicted, an innocent person convicted, we have to go back and say, OK, what went wrong? Is it system area, individual error? How can we fix this system?

DNA is giving us an extraordinary opportunity. That's what this book is all about. It's about the individuals who are convicted, it's their stories in compelling terms, but it's also about what the problems are in the system and some simple reforms to fix it. And that's where I -- really, where I think the focus should be.

NEUFELD: Now, Terry, it would be a tragedy if people walked away from this book or these times of insight as a result of these DNA exonerations and said, Oh, we don't have to worry any more about miscarriages of justice or innoc -- or guilty people getting off, because DNA is the quick fix. It will answer all those questions. And we'll either know, green light, red light, you know, innocent-guilty, it's as simple as that.

The problem is, and the reason we wrote this book, is that most cases don't involve biological evidence. They didn't in the past and they won't in the future. So unless we engage ourselves as a nation and take on these important reforms right now and maybe go forward with the kind of commission that, you know, that Barry's describing, then we are doomed to repeat the same failures in the future.

And you know what's really incredible is, you have someone like Jim Dwyer who goes out and writes a few columns about a case of someone who's been unjustly convicted -- and by the way, he's done it in cases where there is no DNA evidence, and those people were exonerated -- and then on the basis of his columns, the prosecution decides, My goodness, you're right, there's been a miscarriage of justice, and we're going to let this guy go.

There's something fundamentally wrong with a criminal justice system that questions of life and death are decided by attracting a certain columnist to your cause. It doesn't make sense. We have to go back and look at the machinery, see where it broke down, fix it, and make it easier for people to be cleared in the future, and make it easier for the guilty to be apprehended.

GROSS: Well, I want to thank you both very much for talking with us.

SCHECK: Thank you.

NEUFELD: Thanks, Terry.

GROSS: Peter Neufeld and Barry Scheck collaborated on the book "Actual Innocence."

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

GROSS: You're listening to music from the new Django Reinhardt boxed set. Coming up, Kevin Whitehead reviews it. Also, we talk with Dave Eggers about his new memoir called "A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius," about raising his 8-year-old brother after their parents died.

(BREAK)

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest: Barry Scheck, Peter Neufeld

High: Attorneys Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld co-founded the Innocence Project, dedicated to freeing innocent people from jail using DNA tests to do so. They've collaborated on a new book, along with columnist Jim Dwyer, about their efforts. The book is "Actual Innocence: Five Days to Execution, and Other Dispatches From the Wrongly Convicted."

Spec: Capital Punishment; Death; Justice; Trials

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 2000 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 2000 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Attorneys Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld Putting the Justice System on Trial

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: FEBRUARY 23, 2000

Time: 12:00

Tran: 022302NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Dave Eggers Discusses `A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius'

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:30

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

You might think that an author who titled his memoir "A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius" would be a pretty self-conscious writer, and you'd be right. Dave Eggers' new memoir opens with nearly 40 pages of satirical explanations, disclaimers, thoughts on the shortcomings of memoirs, and suggestions of how to read his book.

In "The New York Times" Sunday Book Review, his memoir was described as "going a surprisingly long way toward delivering on his self-satirizing hyperbolic title."

Eggers is also the co-founder of the late magazine "Might" and editor of the current one "McSweeney's." His new memoir is about raising his brother, Toph -- that's short for Christopher -- after their parents died within a few weeks of each other. Eggers was 21 when they died, Toph was 8.

I asked Dave Eggers how he felt about taking on the responsibility of raising his brother at a time when some college graduates take a brief break from major responsibility.

DAVE EGGERS, "A HEARTBREAKING WORK OF STAGGERING GENIUS": I don't think that there were very few, if any, things that I didn't do that I wanted to do because of Toph. If anything, it -- I had an, I think, an infinitely better time and more full sort of life with him, because, you know, it was just -- we were constantly entertaining each other, I guess, is the only way to put it. We'd get really stupid together. And I didn't really leave Toph much with baby sitters or anybody because I was terrified that something horrific would happen to him, partly as punishment for my leaving.

But again, we -- there were very few things that -- if any -- that it prevented me from doing.

GROSS: (inaudible)...

EGGERS: I wouldn't have traded it for anything, I mean, not a chance.

GROSS: You mention being afraid that something would happen to your brother, that he might even die if you left him in somebody else's hands.

EGGERS: Oh, sure.

GROSS: I'm wondering if you think having two parents die within, you know, such a short time of each other made you feel that death was just kind of present and there, and, I mean, you know, this isn't supposed to happen that you lose two parents to -- for different reasons at about the same time.

EGGERS: Right. I did get to a point, and I had a sort of a naturally -- I grew up scared to death of just about everything, couldn't watch horror movies, and I was scared of the Willy Wonka movie.

GROSS: Wow. (laughs)

EGGERS: The Oompa-men (ph) terrified me, I had nightmares for, like, a year about those guys. But yes, you get to a point where nothing really is all that unexpected, and nothing really surprises you after a while. And in a strange way, I know that it sounds completely unbelievable and strange, but I started thinking, like, maybe we were -- (inaudible) -- it seemed as logical as anything that we were marked, you know, one by one we'd be picked off in one way or the other.

GROSS: Was there a lot of, like, paperwork you had to do in order to become the guardian or whatever your official role was with your brother?

EGGERS: The really funny thing is, is that there's none. And it's come up a lot of times. I don't have a certificate, I don't have an identification card or, like, a plaque or anything, not even a badge, you know. And I thought that maybe we would get something. And again and again over the years, people have asked for something. And I guess -- as far as I know, there isn't something that one can get, like a card from the government or something.

But people always ask, you know, Give me some proof that you're the guardian, or give me -- and it's always the most random people, like somebody who, you know, we just want to sign up for some test, and they want identification. And, oh, what happened recently, he and I went to Mexico, and the woman that I booked the flight with said that I was going to need identification that I was his guardian, because there are very strict rules about transporting minors across the border.

And I told her -- and we got into a big argument over the phone, me and the airline woman. I don't know, it comes up a lot, and it's funny. But no, there's nothing at all. And I guess all these years, I could be -- I could have faked the whole thing, I could have kidnapped him and stolen him from somebody else and pulled the whole thing off. Nobody will know, I guess.

GROSS: You know, when you started to take care of your brother, you were, you know, comparatively close in age. You were about 21, he was about 8. And you write in your book, you know, "His brain was my laboratory, my depository. Into it I can stuff the books I choose, the TV shows, the movies, my opinion about elected officials, historical events, neighbors, passers-by. He's my 24-hour classroom, my captive audience, forced to ingest everything I deem worthwhile."

How long did that last? (laughs)

EGGERS: It's still going on.

GROSS: Really?

EGGERS: He's not listening as much any more, but, yes, I mean, I think that's the role of any parent. You know, it's kind of fun. You have -- they have no choice but to listen and digest everything you say, until they know better, at least. You've got them until they're maybe 16 or, you know, maybe 14. And then they found out you're full of it, you know.

But there was a time at the very beginning when I took that role very seriously, and we had -- used to have a lot of educational talks. And I thought about home schooling for a while. And...

GROSS: Did you teach him about rock bands? (laughs)

EGGERS: Oh, no, you know, sure, well, that's part of it too. You know, we would sit at dinner, and I would read from the encyclopedia, you know. I was a real moron about it all. And -- but he was very -- he was a very willing pupil and very earnest about it himself. And we've -- you know, we were sort of -- thought we were doing some kind of reinventing of the familial situation.

And -- but, you know, I got over that after a little while. I mean, the really serious, you know, home education stuff. But otherwise, no, I -- you know, it never ends. That's one of the great advantages of parenting is just having somebody to blather to, and they're obligated to listen.

GROSS: How did the parents of your brother's friends relate to you?

EGGERS: Some of them very normally, some of them strangely, you know, there were some people that were very -- you know, some people just don't know what to say, and they don't know how to deal with you. And there was some funny stuff. I mean, we had neighbors that would burst in -- at one point a neighbor burst into the house wanting to -- I mean, thinking that she was going to catch us all in some terrible situation. I don't know, I mean, she hadn't seen Toph for a couple days in the neighborhood, and so she burst in.

And me and my two brothers were there, just sitting there. And she was, like, What's going on? What's going on? That's what she said, twice, without even knocking. I mean, it was -- it's a weird thing. I don't know if that anecdote makes any sense.

But for the most part, they treated me like a peer, and I tried to will myself and tried to put myself in a position where they would treat me like a peer. I pretended like I knew a little bit more than I did, probably.

GROSS: My guest is Dave Eggers. His new memoir is called "A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius." We'll talk more after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

GROSS: My guest is Dave Eggers. His new memoir is called "A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius."

Your new book is a memoir about raising your younger brother after your parents died, and in the book you have a long set of explanations and disclaimers and so on before the actual book begins, and you describe the memoir as a genre that's inherently vile and corrupt and wrong and evil and bad, but you'd like to remain everyone that we could all do worse as readers and as writers. What makes you suspicious of the memoir as a genre?

EGGERS: Well, I -- that part, I was putting those words into the mouth of somebody that was criticizing me early on for writing one, that that's sort of the assumption of a certain slice of the literary community, that the more decent thing to do is to sort of sublimate your own experiences through fiction somehow, or to -- I -- you know, the more expected and, I guess, socially acceptable way to do it is to change names instead of -- and write the same story in the third person and call it semi-autobiographical.

And the weird -- and so I object to that. I just think that if you're going to write a -- if you're going to write your own story or something that's more or less your own story, you might as well just plow through and do it (inaudible)...

GROSS: You're so self-conscious, you know, in writing the memoir, (inaudible) you're talking know about facing it honestly. But you acknowledge to your readers that, you know, any writer writing a memoir is going to want to be kind of likable to the readers, and that you can kind of strike whatever tone you want to for whatever reason you want to. Was that a really difficult thing for you to figure out who should the narrator be? Who should I be in this memoir? Should I be likable or should I have moments where I really intentionally alienate the readers?

EGGERS: Yes...

GROSS: Should I be ironic or sincere?

EGGERS: Yes, there was all that, and I think all that sort of ends up in the book. I -- and I would imagine that anybody who writes about things in the first person would do the same thing.

I was really loathe to do that. I had never written anything like that before, a long first-person kind of thing. And I felt a terrible guilt about doing it for the same reasons I was (ph) some people don't like memoirs. I've never read a memoir. I've read -- well, I've read one memoir ever. I read Mary McCarthy's "Memories of a Catholic Girlhood." And I read that while I was writing this book, and it was kind of a mistake to have done that during the read -- writing. But I can't say that -- I mean, perfect -- to be perfectly honest, I don't know if I would read this book if I hadn't written it. It probably wouldn't have appealed to me at all.

And -- But I couldn't do anything about the urge to do it. I just sort of felt like I had to put this down, and I had to go through this. And while I was writing it, to sort of fight that guilt about it, and my own reservations about it, I tried to make it (inaudible) it came out in sort of a kind of self-punishment that I threw into the book.

I tried to make myself look as bad as possible as often as possible, and to parody the person that I was, and that -- you know, and the people that we were back then, and all that money and Jack (ph) stuff is, I think, kind of viciously self-parodying.

And that's one way to deal with it. I mean, I was hoping -- I think that inevitably you're going to end up with the nature of this story -- it could get -- it could have gotten really maudlin really quick, and it could have gotten very self-congratulatory very quickly. And I had to combat that all the time.

GROSS: How is your younger brother Toph, who is in part the subject of your memoir, reacting to the kind of public telling of his story?

EGGERS: He literally doesn't know anything going on. He won't hear this, and he hasn't seen any articles at all. And that's the truth. He's studying abroad right now with (inaudible), like, half of his class, and he's busy with school, and that's it. We don't talk about it. And, I mean, of course, he read the book and contributed to it, and we went over all of it, and fixed things and did the dialogue together and everything. But he's too busy with school to care about this kind of stuff, and we don't really burden him with the knowledge of it.

So that's the honest truth. I don't know, when he gets back, it might be a little different. But high school kids, you know, they've got their own thing happening there, and they don't really -- they don't play close attention to these things. It's hard to explain, but it's true.

GROSS: You edit "McSweeney's" now. How would you describe "McSweeney's"?

EGGERS: Oh, I wouldn't. I'd never know how to describe it. I -- it's a journal of things that we find and publish. That's the only true way to describe it. I know it sounds like I'm avoiding, but I don't have any -- it's really just sort of a -- it's an attempt to publish things that might not be published elsewhere, and to give writers a chance to write at whatever length and in whatever context and with whatever subject matter they might want to do, and to experiment with the whole form of the journal.

GROSS: The current issue of "McSweeney's" is -- it's in a box. There's, you know, a bunch of different articles. Each article is bound separately. It's -- each article is, like, its own little book with its own cover. It's on kind of real quality paper with really nice illustrations on each cover. Everything about it seems really expensive. And yet I guess it can't be too expensive. I mean, you don't -- I don't imagine you...

EGGERS: Oh, it was expensive all right.

GROSS: ... you have much of a budget.

EGGERS: Oh, no, it was expensive. We're deep, deep, deep in debt. We didn't -- we were in Reykjavik, where it's printed, and as we were there, they were telling us -- well, we didn't really know, we just kept on adding bells and whistles to the thing and more color here and there and a foldout here and only when they were just about done with it did somebody call and tell me -- called me late at night at this hotel that I was staying at, and -- to tell me how much we were spending. And it was, like, one of these joke numbers that you've never heard before, you know, uttered.

And it just didn't seem real at all. And we -- you know, I mean, we still owe them quite a bit of money. And -- but most of -- we printed 12,000 of them, and then we charged $22 for this issue. And we had to rejigger the math (inaudible) help us out there once we got the price quote.

But what -- you know, we sell all of them, and so we'll make the money back, and we'll be able to pay the bill. But we don't really think about profit margins so much. I always make sure that we break even at some point.

GROSS: When you were editing "Might" magazine, it seems like you were just really annoyed with a kind of -- with the kind of magazine that would almost, like, coronate the person of the moment, you know, the hot person of the day, the hot trend of the day, the hot writer of the moment.

EGGERS: Sure.

GROSS: And, you know, the hot young writer of the moment, and suddenly you're the hot writ -- hot young writer of the moment. It must be a really kind of bizarre predicament to be in.

EGGERS: Yes. No, it's really weird. It's weird because I actually expected to be crucified for this book, and so to have people like it and to, you know, say nice things about it in print and reviews and things is kind of a shock. I am getting crucified here and there by people, and that's what I expected. But the rest of it, yes, the hot thing, I don't know what to do about that. I guess you just have to wait till it goes away and wait till they find the next guy next month.

And in the meantime, though, I will say that the success of the book, and when people talk about the book they talk about "McSweeney's," and when they talk about "McSweeney's" and the book, it helps sell these things, and that helps us in the -- and that enables us to do more of the things we want to do, because of the success of the book, and, you know, the foreign rights selling. That sort of thing, that's enabling "McSweeney's" to do all kinds of stuff that we want to do. And, you know, last week we announced that we're going to start publishing books, and by the summer we'll have four books out.

And we're going to try to use the success of one thing to enable us to do some other quirkier things.

GROSS: Dave Eggers, thank you very much for talking with us.

EGGERS: Oh, thank you.

GROSS: Dave Eggers' new memoir is called "A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius."

Coming up, a review of the new boxed set, "The Complete Django Reinhardt and Quintet of the Hot Club of France."

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest: Dave Eggers

High: Writer and editor Dave Eggers is the founder of the now-defunct cynical, satirical literary magazine "Might" and the current editor of the literary journal "McSweeney's." He has written a memoir about being left to raise his 8-year-old brother after both his parents died. Eggers was 21 at the time. The memoir is called "A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius."

Spec: Art; Media; Families; Children

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 2000 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 2000 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Dave Eggers Discusses `A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius'

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: FEBRUARY 23, 2000

Time: 12:00

Tran: 022303NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: New Collection of Records Offers Overview of the Work of Guitarist Django Reinhardt

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:52

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

GROSS: Guitarist Django Reinhardt was a gypsy who lived in France. He was born in 1910. When he was a teenager, his left hand was permanently damaged in a fire, giving him only limited use of the two smallest fingers on the hand used for fretting the guitar.

Despite that, Reinhardt became the first European jazz musician to win the admiration of American musicians, and he remains a major influence on guitarists in or out of jazz. His music is used in the latest Woody Allen movie, "Sweet and Lowdown."

A new collection of records Reinhardt made over a 13-year period offers an overview of his work. Jazz critic Kevin Whitehead says, this is the real stuff.

(AUDIO CLIP, JAZZ GUITAR EXCERPT, DJANGO REINHARDT AND QUINTET OF THE HOT CLUB OF FRANCE)

KEVIN WHITEHEAD, JAZZ CRITIC: Django Reinhardt's guitar playing would have been startling even if he'd had full use of his left hand. His timing was uncanny.

Django's 1930s recordings with his French band recall some of Louis Armstrong's '20s records in this respect. While the rhythm section plays a fairly stiff two-beat march, he's loose as air, circling the beat, as on Duke Ellington's "Solitude."

(AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, "SOLITUDE," DJANGO REINHARDT AND QUINTET OF THE HOT CLUB OF FRANCE)

WHITEHEAD: One musician who could keep up with Reinhardt was his partner in the so-called Quintet of the Hot Club of France, violinist Stefan Grapelli (ph). Grapelli plays on much but not all of the new six-CD box with the poetic title, "The Complete Django Reinhardt and Quintet of the Hot Club of France Swing and HMV Sessions, 1936-1948." It comes from the mail order house Mosaic Records of Stamford, Connecticut.

As one expects from Mosaic, there are some previously unreleased pieces, and the box includes a booklet with lots of historical photos and excellent notes by guitarist Mike Peters.

The Hot Club Quintet's personnel changed a lot over the years, and it sometimes had more or less than five players. But it always had upright bass and one or two rhythm guitars, a string band concept that sometimes parallels hillbilly bands of the 1920s and '30s.

(AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, "CHICAGO," DJANGO REINHARDT AND QUINTET OF THE HOT CLUB OF FRANCE)

WHITEHEAD: It's easy to hear why Reinhardt helped inspire the teenaged Chet Atkins on his way to becoming the king of Nashville cats.

Reinhardt and Grapelli recorded for other labels besides Swing and HMV, but this stuff is typical. The partners split up in 1939 when war broke out in Europe. The violinist spent the war years in London and Django in Paris. A city occupied by the Nazis was a perilous address for a gypsy who was also a jazz musician, two groups in official disfavor.

Even so, Django flourished in wartime Paris, a tribute to his talent, and the fact that some German officers liked jazz, and to the music's recognizably Continental flavor.

Reinhardt wrote tunes in blues form, but he never really sounded bluesy. He also wrote evocative ballads the French soaked up like Bernaise sauce, such as "Nuages," with its perversely misleading intro.

(AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, "NUAGES," DJANGO REINHARDT AND QUINTET OF THE HOT CLUB OF FRANCE)

WHITEHEAD: With Grapelli gone, Reinhardt had replaced violin with the clarinet of Hubert Rostand (ph), which gave the band a new sound and spirit. Meanwhile, Django's playing just got better and better, as on "Rhythemes Futures (ph)," inspired by train rhythms. Almost sounds like he'd been listening to novelty band leader Raymond Scott.

(AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, "RHYTHEMES FUTURES," DJANGO REINHARDT AND QUINTET OF THE HOT CLUB OF FRANCE)

WHITEHEAD: Django's fast, clean articulation was so advanced, it inspired modernists like England's John McLaughlin (ph), the next trans-Atlantic guitar hero.

Reinhardt and Stefan Grapelli were reunited after the war and picked up where they left off. They should have sounded old-fashioned by then, but if anything, the music was even hotter, not least because their rhythm section had limbered up.

(AUDIO CLIP, JAZZ GUITAR EXCERPT, DJANGO REINHARDT AND QUINTET OF THE HOT CLUB OF FRANCE)

WHITEHEAD: Stefan Grapelli continued to play well into the '90s. He died only a couple of years ago. Django Reinhardt passed away in 1953, but his music has lived on in countless reissues since then.

Part of his appeal, then or now, is that his music audibly reflected his European roots as well as his love of jazz. And since the 1960s, that mix has typified many fine improvisers from the Continent, but none has grabbed American fans the way Django did. It's as if he so epitomized what a European jazz musician could be, they never needed to look any further.

GROSS: Kevin Whitehead reviewed "The Complete Django Reinhardt and Quintet of the Hot Club of France: Swing HMV Sessions, 1936-1948," on the mail order label Mosaic in Stamford, Connecticut.

FRESH AIR's executive producer is Danny Miller. Our engineer is Audrey Bentham. Dorothy Ferebee is our administrative assistant. Roberta Shorrock directs the show.

I'm Terry Gross.

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia, Kevin Whitehead

Guest:

High: Jazz critic Kevin Whitehead reviews "The Complete Django Reinhardt and Quintet of the Hot Club of France Swing/HMV Sessions 1936-1948."

Spec: Art; Music Industry; Media

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 2000 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 2000 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Stefan Grapelli continued to play well into the '90s. He died only a couple of years ago. Django Reinhardt passed away in 1953, but his music has lived on in countless reissues since then.

Part of his appeal, then or now, is that his music audibly reflected his European roots as well as his love of jazz. And since the 1960s, that mix has typified many fine improvisers from the Continent, but none has grabbed American fans the way Django did. It's as if he so epitomized what a European jazz musician could be, they never needed to look any further.

GROSS: Kevin Whitehead reviewed "The Complete Django Reinhardt and Quintet of the Hot Club of France: Swing HMV Sessions, 1936-1948," on the mail order label Mosaic in Stamford, Connecticut.

FRESH AIR's executive producer is Danny Miller. Our engineer is Audrey Bentham. Dorothy Ferebee is our administrative assistant. Roberta Shorrock directs the show.

I'm Terry Gross.

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia, Kevin Whitehead

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.