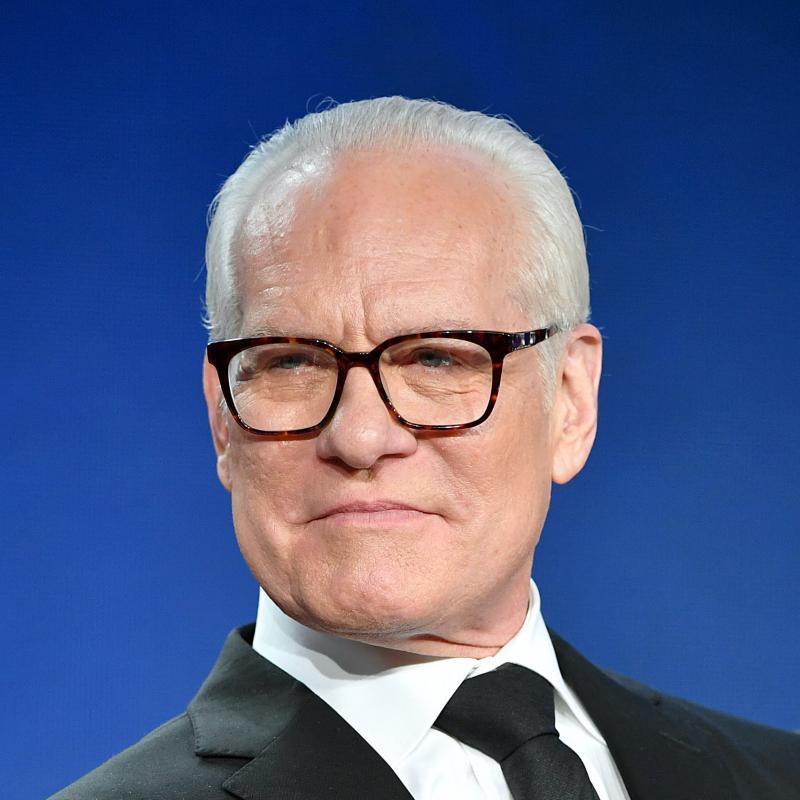

Tim Gunn: On And Off The Runway, 'Life Is A Big Collaboration'

"Make it work," the fashion guru tells designers on Project Runway. But life hasn't always "worked" for Gunn. He talks with Terry Gross about being bullied, being gay in the '60s and '70s, and how his mother thinks he should "dress more like Mitt Romney."

Other segments from the episode on February 5, 2014

Transcript

February 5, 2014

Guest: Tim Gunn

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. We know from "Project Runway" that my guest, Tim Gunn, is very serious about the design of clothing. But he can also be really funny talking about fashion. He's become famous as a mentor to designers, but his personal story has inspired people too.

He's offered his experiences as an example of how you can turn your life around after being in such despair you'd tried to end it, which is what he tried to when he was 17. On "Project Runway," Gunn was the mentor to the fashion designers in the competition. On his new Lifetime reality series, "Project Runway: Under the Gunn," three "Project Runway" alumni each have a team of designers to mentor. Each week a designer is sent home by the judges. The final designer left in the competition and that designer's mentor will be the winners.

Tim Gunn had an academic career before television made him famous. He's the former chair of the Fashion Design Department at Parsons The New School for Design. I spoke with Tim Gunn about clothing and his life. Tim Gunn, welcome to FRESH AIR. It is a pleasure to have you on the show. So you say that, you know, what you wear sends a message to people, whether you know it or not, whether you're thinking about it or not.

You're on the radio, so people cannot see what you are wearing. In fact, I cannot see what you are wearing because you're in a studio in New York and I'm at a studio in Philadelphia. Would you tell us, please, what you are wearing?

(LAUGHTER)

TIM GUNN: You know, Terry, this is what I love about radio. I mean I have a whole series of meetings today. I've come from some, I'm going off to others. I'm wearing a suit and a shirt and a tie, and I'm wearing some boots that are not fashion boots, they are winter weather boots because there's slush and snow out there.

So I have to say, though, I am an individual who is always aware of how he's presenting himself. And I've certainly developed that awareness when I was teaching because I'm a role model in a manner of speaking for my students, and I have to say there is no population that is worst dressed than academics.

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: They are horrible. I actually work with people who - they weren't my faculty. When I was chairing the Fashion Department, I had - I won't say rules, but there were certainly expectations. But when I was in a larger academic community, I actually knew of fellow faculty members who wore pajamas. I mean can you - I mean literally pajamas with soccer balls on them and elephants and you name it.

I thought this is horrifying, horrifying. What does this - what message does this send to your students?

GROSS: So what message are you sending by - when we see you on television, anyways, you're wearing a suit, a very fine suit. By fine I don't necessarily mean expensive, but like well-fitting, you know, really handsome, yeah.

GUNN: Well, thank you. I mean I will share with you that I really believe in shopping on a budget, and I don't believe for a moment that that compromises how good you can look. And this company has a name that I find somewhat regrettable because it's not a sexy name, but it's a company out of The Netherlands called SuitSupply, one word, and it's all menswear, it's very stylish, and it's very affordable. So that's important to me.

And the message I'm sending is that I have respect for myself, I have respect for you, I'm taking the world seriously, and let's navigate the world with some style.

GROSS: So I'll tell you what I'm wearing.

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: I'd love to hear what you're wearing. I'm sure it's not pajamas with soccer balls.

GROSS: It's not pajamas with soccer balls. That's the good news. The bad news is what I'm wearing is black corduroy jeans with a grey zip-up fake leather jacket and a black sweater underneath it, and then a scarf, because I get cold easily. But I wanted to ask you about this. The jacket I'm wearing, it's like fake leather. I like leather a lot. I'm not - I know you're not into using fur, out of respect to animals.

GUNN: Yes.

GROSS: I don't know how you feel about leather.

GUNN: Well, I've changed my - I mean, I've altered my position. I used to say that until the leather gets - the fake leather becomes more believable, I wouldn't consider it. It's very believable these days. I would wear fake leather in a heartbeat.

GROSS: Phew, OK.

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: You sound as though you look very chic.

GROSS: Oh, good, OK. So here's my other question about the jacket I'm wearing. You know, there's something that's called pleather. It's kind of like - what does that stand for, polyester leather or something?

GUNN: Yeah, it's a speedier way of saying faux leather, pleather.

GROSS: Right, it's like fake leather. So - and pleather just always sounded so, like, fake, but now I see ads for vegan leather, and vegan leather, it sounds so righteous. It's like I am such a good person, I refuse to harm animals with leather. So the garment I am wearing is a righteous garment. It's not fake anything.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: It stands for my principles. It's vegan leather. And I thought like, wow, what incredible branding to go from, like, it's fake to, like, it's so righteous.

GUNN: But you know what it makes me think?

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: What?

GUNN: The term vegan leather makes me think that you'd peeled a carrot and took the skin and made a jacket out of it.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Yum.

GUNN: How about it?

GROSS: So in one of your books you tell what I think is a really hysterical story about going to Woodstock dressed entirely inappropriately for the occasion. Describe to us what you wore to Woodstock.

GUNN: Oh, I was wearing gray flannel pants and Weejuns and a...

GROSS: Weejuns, for people who don't know, are these very, like, preppy sandals. I don't mean sandals. I mean...

GUNN: Loafers.

GROSS: Loafers, yes, thanks.

GUNN: And a classic blue blazer with brass buttons. Hey, you know, Terry, what happened to the Weejun? Why hasn't that come back?

GROSS: I don't know. There were two kinds. There was the kind with the tassel and then the penny loafer version.

GUNN: The penny loafer was the one I preferred. But that - great classic style. It should return.

GROSS: In oxblood, yes.

GUNN: At any rate, that's how I arrived dressed at Woodstock, only to sink up to my calves in mud.

GROSS: So did you feel like you were dressed wrong or that, like, all the other thousands of people who were there, who were wearing something between, like, bell bottoms and nothing were wrong?

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: That's very true. I felt as though my little school group and I had landed on another planet. And I had never - certainly hadn't experienced anything like it, hadn't seen anything quite like it and could never have anticipated it. And I couldn't get out of there quickly enough, to be perfectly honest, but upon reflection I'm so thrilled to have had that experience because what a moment in our cultural history Woodstock was, I mean phenomenal.

GROSS: Did you go home and then trade in your flannel pants for bell bottoms?

GUNN: No, no, and that was a school uniform. So I couldn't have done anything about it anyway.

GROSS: So you went in your school uniform?

GUNN: We all did. I mean that's what we wore.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: That's great. How did you feel about having to wear a uniform in general?

GUNN: You know, at the time I found it to be very restricting, and I felt something like a prisoner, but I have recalibrated thinking about the uniform. I find it's very democratizing. You don't have to get up in the morning and think about: What am I going to wear? And for girls in particular, I love a uniform because the fashion pressures on teenagers and younger women are extraordinary.

And living in New York City, I love the private schools that have a uniform, and I have to say I have something of a disdain for those that don't because the fashion competition is ridiculously stupid. In fact it's absurd. I live in an apartment building with a lot of teenage girls who go to private schools, and I am always supporting the ones in the uniforms.

And I hear the other ones talking about how, oh, you know, this is Marc by Marc Jacobs and not Marc Jacobs. And I want to say cry me a river, you little 13-year-old. I mean what is this? It's a crazy, crazy world out there and crazier for some than others.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Tim Gunn, and of course he is the head mentor of "Project Runway," and now there's a new series on Lifetime called "Project Runway: Under the Gunn," in which he mentors the mentors, and the mentors mentor the fashion designers. Let's take a short break; then we'll talk some more. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Tim Gunn, who is famous for "Project Runway," and now he has a new series on Lifetime, which is called "Project Runway: Under the Gunn," in which he mentors the fashion mentors who mentor the designers, and the designers compete with themselves, and the mentors compete with themselves.

Tim Gunn, you always look so poised and centered when we see you on TV. But you've suffered, and you've spoken about that. You've written about it, and you also did a video for the It Gets Better Project, about telling people who've been bullied because they're gay that, you know, hold on, it gets better.

And in your It Gets Better video, you talk about how you tried overdose on pills when you were 17. And I was wondering, like, had something happened right before that that set you across the line into suicide?

GUNN: Well, yes, something did happen. I had been dropped off at yet another boarding school by my parents. I can't even recite the number of schools I went to as a kid because I was constantly running away from them. I mean, it's so ironic that I would become a career educator because I hated school so profoundly. And it wasn't the learning experience that I hated. I hated the social aspects.

So I'd been dropped off at yet another boarding school, and it was that first night. I had taken I don't even know how many prescription medications out of my parents' medicine chest, and I didn't even know what they were. I mean I knew they were prescription, but I didn't know what they were. And I took all of them, probably easily 100 pills.

And I was so resigned to just going to sleep and not waking up. And that next morning, I did wake up, and I was completely disoriented. The room was spinning. I couldn't believe I was still alive. And that morning I ran away. And I found a little hiding place, and I hid out for hours, and my disorientation didn't get better.

So I went to the school administrators and told them what I had done, and then of course they brought in a doctor. And in spite of the fact that I was still there, they took my blood, pumped my stomach. There was still stuff in it. Anyway, it's a longwinded way of saying yes, there was a catalyst. It was that I was being dropped off at yet another school.

I had no reason to believe that that experience was going to be any better than anything else that I had gone through, and I thought I don't like this life. This is really rotten. And I want to just stop it.

GROSS: Why had you been to so many boarding schools? Was it you who wanted to leave, or were you thrown out?

GUNN: Oh no, I wasn't thrown out. I mean, I was a diligent student, and I wasn't a troublemaker. I was constantly running away. I hated interacting with people. Also I should add, and actually some of it you can hear now, I had a very debilitating stutter, and that was very limiting for me socially, and it of course was rife for teasing, and people would imitate me, or they'd want to engage with me, would want me to speak because they wanted to hear the stutter and laugh.

So that exacerbated everything that I experienced, and it added a painful dimension to every kind of interaction, whether it was with peers or whether it was with doctors.

GROSS: Did you know then that you were gay, and did that contribute to your depression and your thought that you wanted to end it?

GUNN: You know, I won't say that I knew I was gay. I knew what I wasn't, and I certainly wasn't attractive to girls, but I didn't know what I was. I called myself nonsexual. At that young an age I did. I mean it was like I don't have a sexual bone in my body. There was zero attraction in any direction, or either direction, I should say. Well, no, I'll say any. It doesn't just have to be men or women, it could be anything.

GROSS: Did you feel like there was something wrong with you because you didn't feel sexual?

GUNN: Well, at the time I was on a sort of moral high horse, and I in some ways associated myself with the clergy, even though I wasn't a religious person. And I thought this is all perfectly acceptable. I didn't think of it as being something wrong. It may have been unusual, but then I was an odd kid. I mean, I wasn't a sports person, though I finally - I mean I shouldn't say finally, I was a very good competitive swimmer, in fact I held a couple of New England records for a while.

And I loved swimming because, as I still say about it, it's clean and you don't sweat.

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: And it's a solitary sport. I mean, there are relays where you're swimming with other people, but it's something you can do alone, like running, but it's not clean and you do sweat. And I, you know, I actually begged my parents for piano lessons, and I ended up studying the classical piano for 12 years. I mean, I was just - and I would rather be in my room alone with my Legos and my books than play with people.

GROSS: You know, you had told us about that funny story about dressing in your school uniform at Woodstock. Was that before or after the suicide attempt? Which school was - was that the school that you had just arrived at that you were describing?

GUNN: Oh no. No, no, no. Because the suicide attempt school, I was there for a day and a half.

GROSS: And then you left.

GUNN: By the time I got back to the headmaster's home, actually, and wept and confessed everything, they already knew. They found the pills in a trashcan, or they found the pill containers. They already had a doctor on call. And my father had already come up from Washington. So I arrived in his house, and my father was there, so - and my father took me to the hospital.

And what I didn't expect was that I'd spend the next two and a half years there.

GROSS: Where, in the hospital?

GUNN: Uh-huh. Yes, I haven't - I don't know that I've said that to anyone.

GROSS: Wow.

GUNN: I mean more precisely, two years and four months. So I had a very major intervention there and couldn't run away, or I would have.

GROSS: Was that considered like rehab? Was it like a rehab setting, or was it...

GUNN: It was a psychiatric hospital for adolescents.

GROSS: Was it the right thing to do, you think, to...

GUNN: Yes, it saved my life. And the doctor I had there, and he was actually my third doctor, because I was a very difficult patient, and doctors would - I won't say give up on me, but they'd pass after about three months. And Dr. Philip Goldblatt(ph), God bless him, of Newhaven, Connecticut, wouldn't let go. And he - I saw him five days a week for almost two years.

GROSS: What made doctors give up on you before that, do you think?

GUNN: They would lose patience. I was - I mean I will say this about myself. I'm smart, and I'm canny, I figure things out quickly, and I knew how to manipulate and maneuver around them, and I knew how to simply be intractable and difficult. And for Dr. Goldblatt, I mean our first couple months together, he was with me almost all day every day, and it was a matter of guess what, you can't escape me, and if you want to keep playing these games, I'm here to say, OK, play them, I'm just, I'm going to watch it all happen, but I'm not leaving. And I didn't believe him, and I tried to push all of his buttons so that he would reject me, and he wouldn't stand for it. And I love that man. In fact, I tear up when I think about him and what he did for me.

GROSS: Do you think about him when you're mentoring people?

GUNN: I do.

GROSS: Did sexual orientation come up in your many sessions with him? Was that something you could confide in him?

GUNN: You know, it came up later, because I would have - after having had this intense relationship with him and then being discharged, I would have an occasional booster shot with him where I would make an appointment and return to see him. And one of those was when I accepted my sexual orientation, and I went to see him. And I just said I just want to share this with you.

And we talked it through, and we agreed that I'd been in denial for a long time and just couldn't allow this to come to the surface, and it was an epiphany for me to be able to acknowledge it and to be able to accept it and not feel hateful about it.

GROSS: Do you have a sense of why - tell me if I'm pushing too hard on any of this.

GUNN: No.

GROSS: OK. Do you have a sense of, like, why you couldn't accept it for a long time?

GUNN: Well, when I think about the era, it's the 1960s, late 1960s going into the early '70s, and it was considered to be something that you fixed. I mean there were - this was an adolescent psychiatric hospital. So people were teens into early 20s. And there were some people there who were there to have their gayness fixed.

So for me it was like, oh, well this is something that you - it's like treating a disease. You have to do something about it.

GROSS: Did you fear that if you said anything about thinking that you were gay that somebody would try to fix you at the hospital?

GUNN: Well, I remember thinking I have enough issues without adding this to the list.

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: Yeah, I mean I thought, oh God, but for the grace of God there go I. And also, on the one hand I'm not envious of any young person who's going through a struggle with their sexual identity. I'm not envious at all. On the other hand, there are so many more and more positive role models these days.

I mean when I was a kid, who were the gay people? They're the decorators in the Doris Day movies, they're the fashion designers. They are flitting about. I mean, I think about Paul Lynde on "Bewitched." I mean, he was a caricature. And today, we recognize that every flavor of humanity comes in every possible size and color and shape. And we have so much more awareness of the diversity of everyone.

I mean whenever anyone tries to stereotype gay men, it's like wait a minute, there are just as many who live like slobs.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Tim Gunn will be back in the second half of the show. His new fashion competition on Lifetime is called "Project Runway: Under the Gunn." I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross, back with Tim Gunn. After a long academic career in design, he became famous as a fashion mentor on the fashion design competition "Project Runway." He has a new series on Lifetime called "Project Runway: Under the Gunn," which is a competition between fashion designers, as well as a competition between their mentors.

Your father - I was so surprised to read this - your father was an FBI agent. And he became...

GUNN: Yes.

GROSS: ...under J. Edgar Hoover, and he became Hoover's ghostwriter.

GUNN: Yes.

GROSS: What did he write for Hoover?

GUNN: He wrote all of his correspondence, all of his speeches and his books.

GROSS: Was your father very macho kind of guy?

GUNN: Yes. Yeah. He was, you know, had a beer in his hand, watching football every Sunday.

GROSS: Your father must have had some clue that you were gay. Did...

GUNN: Oh, absolutely. I mean, well, he certainly knew - I mean, I wasn't throwing the football around. I wasn't interested in sports. I - but, you know, I'm going to choke up again. He was an incredible man. In spite of all the trouble that I gave him and the disdain that I so frequently felt for him, first of all, he was always there in a crisis. Who was there after the suicide attempt? He was. My mother wasn't, because she would fall apart. But also, the whole sports thing, he was - he became the little league coach because he wanted to support me and wanted me to be playing little league. Ha. That wasn't going to happen. But when I took to swimming, he became the swim coach. And it was just such a wonderful thing, because he was there at every practice. So, in many ways, he was really extraordinary.

But, you know the one curious, curious matter that I have, also upon reflection, I was the kid who came home from school bloody and bruised with so much frequency. I mean, it could happen at...

GROSS: Because you were bullied?

GUNN: Yeah. I mean, at the time I called - I didn't even use the word bullying then, but just teased and beaten up. I was evidently fun to beat up. It was just so easy to do it. You know, my macho father never once took me aside and said, let me show you how to fight back. Let me show you how to throw a punch. Never once. And I find it really curious...

GROSS: And yet...

GUNN: ...at least that I can recall. And consequently, if you have a physical fight with me, I'm a biter and a hair-puller.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: You never came out either of your parents, right?

GUNN: No. No. I certainly did not. And, you know, what purpose would it have served, to be perfectly honest? My mother certainly figured it out when she stopped trying to match-make me with the daughters of her friend. My sister knows. We had a heart to heart, and she was nothing if not supportive.

When all the "Project Runway" stuff happened, I mean, who knew it would become a phenomenon? I thought it was just going to be a little blip, and I was initially just a consultant to the show. I wasn't intended to be on it. But when press started happening and mother would read everything, she certainly knew. And the fact that she didn't choose to speak about it meant that I didn't need to speak about it. It wasn't as though we had an unresolved issue. It's part of who I am. Though she did say to me, when "Project Runway" was about to start and, actually, when I told her that I was going to have this role on the show as a mentor, she said, are they crazy? You're so old.

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: So she asked two things of me: She asked me to dye my hair, and she asked me to lie about my birth date.

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: Well, I'm not going to die my hair. And what purpose would lying about my birth date do? She said, finally, she had said - because she was really begging me to make myself younger than I am. She said it turned out that she'd been lying about my age.

GROSS: Oh.

GUNN: How do you like that?

GROSS: To who?

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Oh, maybe because she was lying about her age.

GUNN: Yes.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: So it was all about her.

GUNN: Exactly.

GROSS: So when you say like what would it have done to come out, I mean, what it would've done was allow you to live in a completely more honest - not completely, necessarily, but in a more honest way of, like, we know I'm gay, so let's just, like, acknowledge it so it's not this kind of thing that we can't ever talk about, like it doesn't really exist.

GUNN: But let me also share the juncture where I was, because I had already been through a fairly long and intense relationship that was over, and painfully over. I don't recall ever feeling this hurt, ever. And it was 1982, so it was the advent of AIDS. The person with whom I'd been for so long revealed to me that he'd been sleeping with just about anything and everything in Washington, D.C. I thought: not only have you delivered the largest dote of the emotional pain I've ever experienced, but I may also have a death sentence now.

So I moved to New York and, quite frankly, he was part of the reason why I accepted the position at Parsons, because we had been together when Parsons had asked me the year before to come and join them, and I said no, thank you. I'm a very happy. But a lot happened in the following year. I moved to New York. I - I mean, AIDS devastated, devastated this nation in the 1980s, and so many young people are so unaware of that. They think, oh, it's HIV. We'll all survive. Well, we didn't.

And I was tested for HIV every year - and sometimes more frequently - for years. So, I certainly wasn't with anyone. I had no desire to be with anyone, and I found out that I really like myself and I don't - I actually like being alone. So I wasn't going to go into a relationship, either. So, this is a long-winded way of saying I wasn't going to bring somebody home to my mother to say, guess what? This is my love interest. We're going to be together, or whatever it may be.

So that's why I say there was no purpose. And I wasn't altering or amending in any way shape or form how I navigated the world or how I interacted with people. I wasn't pretending with my mother to not be gay, but in our household, we didn't talk about sex, ever, I mean, of any kind. We didn't engage in that kind of dialogue. So it wasn't as though I was obfuscating or misrepresenting or, God forefend, lying.

GROSS: Do you think that relationship that you were afraid was not only going to hurt you emotionally, but maybe kill you has, like, affected your view of relationships in the more long-term?

GUNN: For me, personally, most definitely. Do I project it onto other people? No, except to generally agree that men are rats.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: When you say that, you know, after that relationship, you learned that you like being alone, was it surprising to you that, like, you liked being alone, and that you liked yourself, that you could be comfortable with yourself alone?

GUNN: Oh, it was a fantastic, fantastic moment, I have to say. Because so many people have this fear - myself included - about, oh, you know, you can't be alone, and there has to be somebody else. And what are you going do at night and there's no one to talk to, and what do you do on the weekends? Well, you enjoy your own company. And it's very, very liberating, and it makes you feel truly independent. And at this point in my life, the only way I could imagine living with someone else would be if we, in fact, had separate rooms and came together, you know, separate bedrooms, came together for conversation and meals, and it would be much more social. But, I mean - it - though - let me - I'll be perfectly candid. Do I have physical needs? Yes. Do I need them to be satisfied by another person? No.

GROSS: My guest is Tim Gunn. His new fashion competition, "Project Runway: Under the Gunn," is on Lifetime. We'll talk more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Tim Gunn, who everybody knows from "Project Runway," and now his new show, "Project Runway: Under the Gunn." You know, there's a very emotional moment on "Project Runway," where one of the designers explained that he had this secret that he was going to reveal, that he was HIV-positive. And the designers have been given the task of coming up with a design for a fabric that connected to something very personal in their life. And so he had these, like, black pluses, like positive, black pluses on this, like, bright purple background. And it was, like, this really beautiful, vivid design. And then he explained...

GUNN: I remember this profoundly.

GROSS: Yeah. And then you, maybe you can explain why the pluses...

GUNN: This was Mondo Guerra.

GROSS: Yeah. Then he explained why the pluses, why the positives were there. Did you have a long talk with him after that?

GUNN: I remember giving him a huge hug, and we both shared some tears, and I remember telling him how proud I am. And I felt that that was adequate.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

GUNN: And, again, you know, for him, that was his own way of coming out, because his family didn't know.

GROSS: Oh, really?

GUNN: Yes.

GROSS: Oh, you know, it was in that season...

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: It was in that season that you say we have a surprise guest for everybody, and everybody's thinking it's going to be a big celebrity. And you open the door, and in walk everybody's mother.

GUNN: Yes.

GROSS: And everybody's, like, in tears. All the designers, all these young designers are in tears. Oh, my mother. It's so great to see her. I felt so lost without her. And I was thinking, if somebody opened the door when you were that age and said, guess what? It's your mother, like...

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: ...you probably would've had a different reaction.

GUNN: Well, I probably would have.

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: And my mother would've proceeded - well, my mother would've probably asked: What are you doing on a fashion design competition?

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: What is this? What's going on? You know, I have to tell you, even having ascended - I'll use that word - having ascended to the position of chair of the Fashion Design Department, having become the mentor on "Project Runway," my mother was still so critical of what I would wear. She would be critical of what I would wear on the show. In fact, she would call afterwards and say: Why did they let you do - wear such and such, and that tie didn't look good with that shirt.

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: And then I remember, so profoundly, going to her home - home, I'll call it - for Thanksgiving, and walking through the front door. And she looked me up and down and she said - studying me with little, squinty eyes - she looked at me and she said: Why can't you dress more like Mitt Romney?

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: Well, you can imagine my reaction.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: What kind of clothes did she wear?

GUNN: Well, again, God bless her. She would infirm, in her mid-80s. So whatever was comfortable. And I didn't...

GROSS: But when she was younger. When she was younger.

GUNN: Oh, she was quite chic and stylish.

GROSS: Was she?

GUNN: She was. And my grandmother was quite the fashion plate. In fact, you never saw my grandmother without a hat, ever.

GROSS: Was it the kind of hats with veils on them or...

GUNN: No.

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: No.

GROSS: Because I remember when that was popular. Yeah.

GUNN: No. They were, they were very chic, very stylish hats.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

GUNN: And I had a great aunt who was petite, and couldn't find anything in stores that really fit her very well or that she liked. She had all of her clothes made, and they all had a label, custom-made for Virginia Jones, though she was Aunt Si - S-i. How did that happened, I don't know.

GROSS: So maybe you got some of your fashion sense from your mother, in spite of how she would berate you.

GUNN: Well, she was stylish. Yes, exactly. She was stylish and she, unlike a lot of women of that time, she worked. She was a real estate broker for 30 years. But before that, before she actually had - gave birth to me, she began the library at the CIA. So...

GROSS: Oh, you're kidding?

GUNN: ...library science was really her area. It was interesting.

GROSS: Wow.

GUNN: Yeah.

GROSS: Oh, that's interesting.

GUNN: So it was when the CIA was just beginning.

GROSS: Wow. So we've talked, you know, about your life and about clothes. You wear suits, usually, when you're on television...

GUNN: I do.

GROSS: ...and going to meetings and stuff like that. When you're spending, basically, time at home and you know no one's likely to be visiting on that day and you're not going out - at least not for a while - what do you wear? Do you wear clothes as if somebody would see you? Or do you just - do you have like sweatpants and a sweatshirt that you wear at times like that?

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: Actually, I don't own either.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

GUNN: But I - I mean, home, in winter weather, I'll wear jeans and a turtleneck. And if it's - when the weather is warmer, khakis and just a shirt without a tie, or even a T-shirt. So, yeah, I have to tell you, this reminds me of a question I asked Dolly Parton when I was lucky enough to interview her. I told her that I had read that when she and her husband go camping, she's without hair and makeup. And it's just that Dolly, and people probably wouldn't even recognize her. And she said to me: Are you kidding? She said: I go to sleep in full hair and makeup.

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: And I asked her why. She said, what if there's a fire? I don't want to disappoint the firemen.

(LAUGHTER)

GUNN: Isn't that great?

GROSS: That is great. But you don't feel that way about yourself.

GUNN: No. No, no, no, no, no. I mean, I'm not - I mean...

GROSS: Well, wait. I mean, you're...

GUNN: Someone comes to the door...

GROSS: You're not designed in the way Dolly Parton is, and you...

GUNN: No. Thankfully.

GROSS: You don't have the full hair and makeup thing. It's just like really put-together suits.

GUNN: Yeah.

GROSS: You know.

GUNN: I mean, and Terry, I have to tell you, there's not a single day I don't thank my lucky stars that I'm a guy.

GROSS: Yeah, tell me...

GUNN: I don't envy women one bit.

GROSS: Tell my why. Because I'll tell you, just speaking for myself, it is so, like - getting nice clothes is such a frustrating experience. So many of the fashions I think are just, like, really hideous, or totally inappropriate for me. And I'm really short, so that's a problem, too. So clothing - you know, I think clothes are great, if only I could find ones that fit, you know. But tell me your frustration.

GUNN: Well, I mean, I'm not frustrated. But, I mean...

GROSS: Oh, right. Because you're a guy. Right.

GUNN: Yeah. Because for guys, it's so much easier. The clothing options are fewer. The grooming options are not insurmountable. I never think about doing anything cosmetically altering, as in Botox or fillers or, God forefend, cosmetic surgery.

GROSS: Thank you.

GUNN: I don't have to worry - I don't think about dyeing my hair. That's not going to happen. I just am who I am. And for women, there's so many more pressures. And it's - I just feel lucky to be the gender that I am.

GROSS: Just one more thing I just want to say: Because you come off as so, like, totally poised on TV and so totally together, both visually and, you know, emotionally, I really appreciate that you're willing to talk about the times in your life when you didn't feel together and how you kind of came out, you know, the other end of that. I think it's really important to hear. So thank you.

GUNN: Well, thank you for letting me talk about it. May I add one thing on that topic, though?

GROSS: Please.

GUNN: I want anyone listening and hearing the story about my troubled adolescence, I hope it was clear that I didn't come out of this alone. I mean, life is a big collaboration, and when you're tackling something that's painful and troubling and is causing you such desperate grief, that you think life's not worth living, you need to reach out. Reach out before then, actually.

Reach out to people whom you trust, people who will reach back and offer you some solace and some guidance, because it doesn't happen alone. And if I had been just left on my own, well, I wouldn't be here. I simply wouldn't be. And I'm glad I'm here, and there's not a single day I don't thank my lucky stars and say I'm the luckiest guy alive.

And I will also say that I wouldn't take back that pain and that anguish for anything, because it's helped formed who I am and it's helped me appreciate the joyous moments of life, of which there are many.

GROSS: Tim Gunn, it has just been wonderful to talk with you. Thank you so much.

GUNN: Well, thank you, Terry. It's been a joy talking to you, and I thank you for your very thoughtful questions.

GROSS: Tim Gunn's new fashion competition reality series "Project Runway: Under the Gunn" is on Lifetime. Coming up, Maureen Corrigan reviews two entertaining novels that may help you escape the winter gloom. This is FRESH AIR.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. Snow, rain, ice and general gloom getting you down? Our book critic Maureen Corrigan recommends two novels - one new, one just published here in the U.S. - that she says are fine literary antidotes to the winter blues.

MAUREEN CORRIGAN, BYLINE: In the opening paragraph of "Moby-Dick," Ishmael tells us he takes to sea whenever he feels the onset of a damp, drizzly November in his soul. I know how he feels. Whenever the frigid funk of February settles in, I, too, yearn to get out of town. This year, I have, thanks to two exquisite vehicles of escape fiction.

Rachel Pastan's "Alena" and Katherine Pancol's "The Yellow Eyes of Crocodiles" are both smart entertainments perfect for curling up with on a winter's night. Admittedly, they both fall into that much-disputed category of women's fiction, but I urge male readers not to feel automatically excluded, much as we women readers have learned to gamely step aboard boy's-only clubs like that of, say, The Pequod.

Speaking of "Moby-Dick" and opening passages, Daphne DuMaurier's 1938 novel, "Rebecca," is a near-rival to Melville's masterpiece when it comes to the fame of its first line: Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again. You'll hear an echo of that line at the beginning of Rachel Pastan's "Alena," because "Alena" is an inspired reworking of DuMaurier's "Rebecca," which itself was an inspired reworking of "Jane Eyre."

As in "Rebecca," our narrator here is unnamed - a sign of how little sense of self she possesses. Pastan's narrator, who describes herself as a moth, works as a curator's assistant at a Midwestern art museum. Accompanying her odious boss to an art festival in Venice, she meets a tormented-but-charismatic gay man named Bernard Augustin, who's the founder of a renowned contemporary art museum on Cape Cod called the Nauk.

Faster than you can say, Maxim de Winter, the gloomy Bernard and our naive narrator bond platonically over cappuccinos, and he invites her to become the Nauk's new curator. That position is vacant, because the former curator - a sleek, celebrated beauty named Alena - mysteriously vanished one night, two years earlier, into the dark waters off Cape Cod.

Pastan's "Alena" is so eerie and elegantly suspenseful, that I could see myself rereading it, the way I reread "Rebecca" every few years or so. One of "Alena's" distinctive pleasures is its deep familiarity with the contemporary art world, real and imagined. We hear, for instance, about extreme art exhibits, where enormous collages of cotton and bone hang from the ceiling, and dead sardines are nailed to gallery walls in great, glittering waves of decay.

The Nauk museum itself is a brilliant riff on the Gothic mansions of yore: a modernist glass structure built into sand dunes, it conceals a labyrinth of cobwebby secrets, and one vengeful female ghost bent on evicting our clueless narrator.

The recently deceased Hollywood star Joan Fontaine played the mousy heroine in Hitchcock's film of "Rebecca." I could see a modern-day Joan Fontaine-type playing the heroine of "The Yellow Eyes of Crocodiles," should a film version ever be made. Katherine Pancol's novel was an immediate bestseller when it was published some years ago in Europe, and it's easy to see why.

This is a delicious French romp, replete with affairs and wit and screwball plot twists. The story centers on a shy scholar of the Middle Ages named Josephine, whose husband has deserted her and their two daughters in order to run off to Kenya with his sexy mistress, where he's managing a crocodile farm that supplies illegal skins to China.

In order to make ends meet back in Paris, Josephine agrees to a scheme hatched by her wealthy-but-bored older sister: She, Josephine, will ghost-write a medieval romance novel while her glamorous sister will do the promotion and get the credit. Of course, the novel becomes a blockbuster, ethical dilemmas ensue, more marriages fall apart, and more affairs are sparked.

The delicious draw of "The Yellow Eyes of Crocodiles" is Josephine's transformation from field mouse to falcon. Not only does she eventually stand up to her domineering sister, but, more dramatically, to her contemptuous teenage daughter, a girl, Josephine realizes, who has no use for love, tenderness or generosity, who faces life with a knife between her teeth.

Though they're very different in tone, both "Alena" and "The Yellow Eyes of Crocodiles" are escape fantasies about shy, book-wormy types triumphing over glossy power divas. I don't know about you, but that's a fantasy that pretty much always works for me.

GROSS: Maureen Corrigan teaches literature at Georgetown University. She reviewed "Alena" by Rachel Pastan and "The Yellow Eyes of Crocodiles" by Katherine Pancol.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.