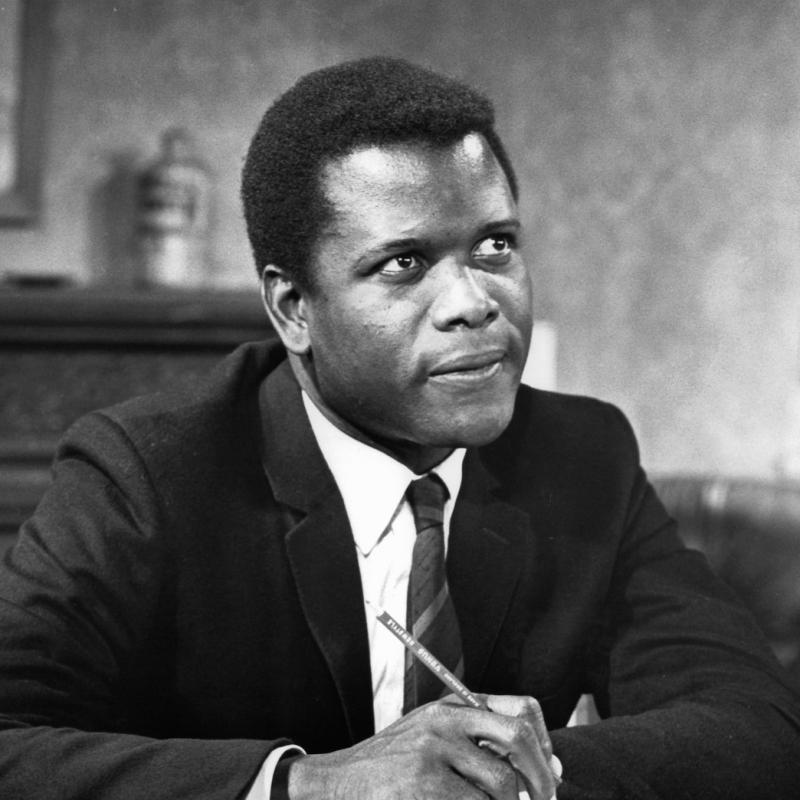

Oscar Winner Sidney Poitier

The leading African-American actor of his generation and the first African-American to win the best-actor Oscar, Sidney Poitier may be best remembered for the classic In the Heat of The Night. That film took a best-picture Oscar; it's out now in a 40th-anniversary edition DVD.

Other segments from the episode on January 18, 2008

Transcript

DATE January 18, 2008 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Sidney Poitier on his life and career

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm David Bianculli, TV critic for tvworthwatching.com,

sitting in for Terry Gross.

"In the Heat of the Night," the landmark movie starring Sidney Poitier as

Virgil Tibbs, a Philadelphia homicide detective who investigates a murder in

the bigoted deep South, was re-released on DVD this week in a special 40th

anniversary edition. Today on FRESH AIR, we hear from Mr. Tibbs himself,

Sidney Poitier.

In the 1950s and '60s, Poitier starred in a string of films that addressed the

racial tensions of the time, films like "The Defiant Ones," "Lilies of the

Field," "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner" and "To Sir with Love." In 1963, he

became the first African-American to win an Academy Award for Best Actor.

Since then, Denzel Washington and Forest Whitaker also have won Oscars in that

same category.

Terry Gross spoke to Sidney Poitier in 2000, at the time of the publication of

his memoir, "The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography."

TERRY GROSS, host:

Let me talk with you about a scene from "In the Heat of the Night." In that

film, Rod Steiger plays a local police chief in a Southern town. You're a

homicide cop from Philadelphia passing through this Southern town, but you're

arrested for being suspicious because you're a black man from out of town

carrying money in your wallet. The police chief doesn't really believe that

you're a cop, so he calls your boss in Philly. And your boss suggest that you

stay in this small Southern town to help them solve this big murder case that

they're working on because they don't have cops who are nearly as experienced

as you are.

So in this scene, you and Rod Steiger, who's still very skeptical of you, go

to question one of the leading white businessmen in town. And I'll just

explain in case it's confusing as our listeners hear it, that as you're

questioning him, the businessman slaps you and then without missing a beat,

you slap him right back. Here's the scene.

(Soundbite of "In the Heat of the Night")

Mr. LARRY GATES: (As Eric Endicott) Let me understand this. You two came

here to question me?

(Soundbite of rooster crowing)

Mr. SIDNEY POITIER: (As Virgil Tibbs) Well, your attitudes, Mr. Endicott,

your points of view are a matter of record. Some people--well, let us say the

people who work for Mr. Colbert, might reasonably regard you as the person

least likely to mourn his passing. We were just trying to clarify some of the

evidence. Was Mr. Colbert ever in this greenhouse, say, last night about

midnight?

(Soundbite of two slaps)

Mr. GATES: (As Eric Endicott) Gillespie?

Mr. ROD STEIGER: (As Gillespie) Yeah?

Mr. GATES: (As Eric Endicott) You saw it.

Mr. STEIGER: (As Gillespie) I saw it.

Mr. GATES: (As Mr. Endicott) Well, what are you going to do about it?

Mr. STEIGER: (As Gillespie) I don't know.

Mr. GATES: (As Eric Endicott) I'll remember that. There was a time when I

could have had you shot.

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Sidney Poitier, in your new memoir, you say that's not the way the

scene was originally written. Originally, you didn't slap this businessman

right after he slapped you. What did you do in the original scene, and why

did you want to change it?

Mr. POITIER: The original scene called for the businessman to slap me and

for me to absorb it and leave. I found it reprehensible that the writers

writing for that period would not have written it differently. And I felt

that the natural emotional response to being slapped as--and I'm speaking not

as Sidney Poitier, but I'm speaking as a Philadelphia detective.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. POITIER: That the natural response to a man slapping him, he's going to

slap him right back. And I elected as an actor to do that, because were I the

guy from Philadelphia who was slapped, I would slap the guy right back.

And I thought that that would be, since those kinds of moments were never

found in American films from the inception of films in this country, that kind

of a scene, which would be electrifying on the screen, was always either

avoided, not thought of. And I insisted that if they wished my participation

in the film, that they would have to rewrite it to exemplify that. And it

indeed did turn out to be a highlight moment in that film. But it also spoke

not just of the two characters; it spoke of our time. It spoke of the time in

America when, in films at least, we could step up to certain realities.

GROSS: Let me advance the story a little further and take you to the early

part of your movie career, specifically to "Blackboard Jungle," which was

released in 1954. This was an important film for you. You had one of the

leads in it. This is like the most famous high school film, I think. It

opens with "Rock around the Clock." Glenn Ford plays the new teacher at a

school just filled with juvenile delinquents. And in your first scene, he

catches you and some of the other guys smoking in the bathroom. You're

washing your hands with your back turned toward the teacher for most of the

scene. Let's hear this scene.

(Soundbite of "Blackboard Jungle")

Mr. GLENN FORD: (As Richard Dadier) What's your name, wise guy?

Mr. POITIER: (As Gregory Miller) Me? Miller. Gregory Miller. You want me

to spell it out for you so you won't forget it?

Mr. FORD: (As Richard Dadier) No, you don't have to do that. I'll remember

Miller.

Mr. POITIER: (As Gregory Miller) Sure, chief, you do that.

Mr. FORD: (As Richard Dadier) Or maybe you'd like to take a walk down to the

principal's office right now with me. Is that what you want?

Mr. POITIER: (As Gregory Miller) You're holding all the cards, chief. You

want to take me to see Mr. Warneke, you do just that.

Mr. FORD: (As Richard Dadier) Who's your home period teacher?

Mr. POITIER: (As Gregory Miller) You are, chief.

Mr. FORD: (As Richard Dadier) Well, why aren't you with the rest of the

class?

Mr. POITIER: (As Gregory Miller) Already told you. Came in to wash up,

chief.

Mr. FORD: (As Richard Dadier) All right, then, wash up. Just cut out that

chief routine, you understand?

Mr. POITIER: (As Gregory Miller) Sure, chief. That's what I've been doing

all the time. OK for us to drift now, chief?

Mr. FORD: (As Richard Dadier) I don't want to catch you in here again.

Mr. POITIER: (As Gregory Miller) Suppose I got business here, chief?

Mr. FORD: (As Richard Dadier) Look, how many times do I have to tell you?

Let's go, huh? Come on, let's go!

(End of soundbite)

GROSS: Sidney Poitier, how did you like your role in "Blackboard Jungle?"

Mr. POITIER: I liked it. I liked it. This young guy that I play, he was

really on the cusp of finding himself in useful ways or losing himself to

forces he couldn't quite understand by then.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. POITIER: And so he had some complications. He had some complexities.

He had some depth to him. And I liked playing him.

GROSS: Well, you became the African-American leading man in the '60s. What

were some of the things that you felt you weren't allowed to play or express

as an African-American leading man in the '60s in Hollywood?

Mr. POITIER: That is a very good question. And the true answer is I have no

such imagery of what I was not able to express because, taking the times as

they were, the fact of my career was in itself remarkable.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. POITIER: Just the fact of it, you see.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. POITIER: It would have been a luxury I would not have spent much time on

trying to determine what was missing. What was missing was not so much for

me, but what was missing for the overwhelming majority of other minority

actors at the time.

GROSS: Well, I'm glad you brought that up. What were some of the things you

heard from your fellow actors at the time about stereotyped roles that they

had to play in Hollywood, when you came to Hollywood?

Mr. POITIER: Yeah. Well, you know, most of us, I think, were obliged to

play what was available. I did not. I did not take advantage of that. I

couldn't. It was not what I needed to do for my life. I had elected to be

the kind of actor whose work would stand as a representation of my values.

GROSS: Would you describe Cat Island, the island in the Bahamas where you

grew up?

Mr. POITIER: It's difficult to describe, in that words would be hard to find

to convey the beauty of it, you know. We have the most extraordinary beaches

in the world. The water is of a color and of a luminance that is absolutely

striking. And the life was such that you walked everywhere you went, and if

you had any heavy loads to carry, you would use a mule or a horse or a donkey,

and stuff like that.

GROSS: When you were 10, your family moved to Nassau, I think because there

was--what?--a crop failure on the island.

Mr. POITIER: Well, they were tomato farmers, that's how they earned their

living, and they sold to the middle guys in Florida. And they did that for

many, many years. And when I was about nine and a half or so, the US

government in Florida, on behalf of the Florida tomato growers, placed an

embargo on tomatoes coming out of the Bahamas for reasons, I suppose,

beneficial to the local farmers in Florida. But that devastated the whole

farming of tomatoes in the Bahamas, throughout the islands in the Bahamas, and

especially on Cat Island, which affected my father. And he, having no other

means of making a living, had to move the family to Nassau, which was and

still is a tourist community and a tourist economy. And he had to find work

as best he could somewhere in that new culture.

GROSS: What kind of work did he find?

Mr. POITIER: Well, not much. He found a job, ultimately, working for

someone in a bicycle store. And he wanted to continue farming, but the soil

available was not resilient enough to be useful.

GROSS: You left for Florida, where your brother was living with his family,

when you were age 15. You planned to stay with him; you didn't stay for long.

What was it like to face Southern segregation?

Mr. POITIER: Well, it was an experience, I can tell you. There was some

semblance of it in Nassau when we moved from Cat Island from Nassau. There

was none of it--none, absolutely none of it--on Cat Island. I never developed

any sense of what color would eventually come to mean in the other parts of

the world, and was really unprepared for what I found in Florida at the age of

15.

GROSS: Did you do things in Florida that were considered terrible mistakes

because you didn't understand what segregation meant?

Mr. POITIER: I remember once, my brother, with whom I was living, once I had

arrived there, helped me to get a job within a matter of weeks at Burdines

Department Store. And at Burdines Department Store, I was given a delivery

job because I could ride a bicycle. And I use to ride the bicycle from

downtown Miami to Miami Beach to deliver packages for the pharmaceutical

division of the store.

I went to Miami Beach once to take--as a matter of fact, on my first day--to

take a package to a home. I had the address, and I went to the address and I

rang the bell. And a lady came to the front door and she saw me standing

there, and I said, `Good evening, ma'am. I came to bring you your package.'

And she slammed the--no, first she said, `Get around to the back door.' Well,

I--listen, I'm 15 years old. I don't know the rules, and I couldn't

understand why I needed to go to the back door because there she was standing

there in the front door, and there I was smiling with a package in my hand,

and expecting her to take it. And I said, `Well, here I am, ma'am, and here's

the package.' And I handed it to her. And she screamed at me to get around to

the back door. So she slammed the door in my face at that point. And still

not understanding fully, I decided that the best thing to do was to put the

package down on the steps and I left it there, and I left.

And I went home--actually, it was two days later. I returned from my work,

got home, and it was in the evening, and the house is dark, and I wondered why

there were no lights on in my brother's house. And as I approached the front

door, the door opened suddenly and my sister-in-law grabbed me and pulled me

in and pulled me to the floor, where the rest of the family was kind of like

huddling. And she said to me, `What did you do?' I said, `I didn't do

anything. What do you mean what did I do?' She says, `What happened?' And she

explained to me that the client had come to the house looking for me. And

that was like an introduction, first of all, to the term "client." I'd never

heard it where I came from. And my curiosity was such that I wondered. I

wasn't so much concerned about the client, because I had no experience and no

frame of reference. What I was concerned about was how the effect it had on

the family, and stuff like that.

There were other incidents in Florida that were representative of the time.

You know, America was a different place in early 1943.

GROSS: Your first audition was as a result of a classified ad that you'd read

for the American Negro Theater, which was looking for performers. You say

when you got to your audition, you had trouble just reading the script. You

certainly hadn't been in an audition before--you had no training--but you

didn't have much schooling, either.

Mr. POITIER: No, I didn't.

GROSS: How much schooling did you have, and what were your reading skills

like at the time?

Mr. POITIER: Well, my schooling, I started school in Nassau at the age of

11, and I had to quit. Actually I started school at the age of 10 1/2, like

two weeks after I arrived, and I had to quit at the age of 12 1/2 because my

father was not a man of material means, and therefore every hand in the family

needed to lend itself to the family's survival. So I had to go out to get a

job, and I did, in fact, get a job at 12 1/2. I suppose that my folks

anticipated my eventually going back to school, but it never happened. So

that when I got to New York, I'm able to read but very, very, very--I can't

imagine what level, what grade level, but it wasn't terrific.

So when I went into this place--I could read, for instance, the want ad pages,

and I could recognize words like "janitor" and "dishwasher" and stuff like

that. Just across the page from the want ad page was the theatrical page, and

there was this sign that said "actors wanted." And I went to this address. I

said, `Maybe I can--I tried dishwashing and janitors and all that stuff, maybe

I'll try this.' And I went there, and there was a gentlemen there alone in

this place that looked like--well, it was an empty room with lots of empty

chairs and a small--what I've learned--is a stage. And he asked me, he said,

`Are you an actor?' And I said, `Yes, I am.' He said, `Where have you acted?'

I said, `In Florida.' And he said, `OK.' He gave me a script and sent me up on

the little stage. And he said, `Turn to page 28.' And I did. I read the

page, and then the following page, and then I said, `OK, I'm ready.' And he

said, `OK, you start.' I said, `All right.' And I started reading.

Well, of course, I had never read for anyone in my life except maybe in the

elementary area my first year in school in Nassau. So I started out. I said,

(Speaking slowly) `So, where are you going tomorrow?' So the chap, I guess his

eyes flew open and he looked up on the stage and it all came to him, you know,

that I was a fake. So he came running up onto the stage and he snatched the

script out of my hand, and he grabbed me--I was a kid, you know--and he spun

me around and he grabbed me by the scruff of the neck and my belt in the back,

and he marched me to the door. And on the way he said--these were his words,

as I remember, he said, `Get out of here and stop wasting people's time.' He

said, `Why don't you go out and get yourself a job you can handle?' And as he

opened the door and as he chucked me out, his last line to me was, `Get

yourself a job as a dishwasher or something.' Well!

GROSS: Well, why'd you come back for more after that?

Mr. POITIER: Because, oh, I mean, as I'm walking down the street, heading to

the bus stop to take a bus toward the area where the employment offices were

where I would be going to get a dishwasher's job, I said to myself, `How did

he know that I was a dishwasher, that's how I made my living in New York

City?' And I remembered not having told him that I was a dishwasher. So I

concluded that he presupposed that that would be my limit, I would fall

comfortably in that frame or some such frame. My potential was characterized

by his suggestion. And I thought that, `I cannot let that happen.' I would be

less than I would like to be if he had turned out to have been prophetic when

he made that comment. So I decided, as I headed for the bus station, that I

was going to become an actor, I was so offended by what he said. And I was

going to go back and show him that he was wrong in his assessment of me.

That's precisely how it happened.

GROSS: Well, I thank you so much for talking with us.

Mr. POITIER: Thank you for inviting me.

BIANCULLI: Sidney Poitier speaking to Terry Gross in 2000.

"In the Heat of the Night," in which he starred as Detective Virgil Tibbs, has

just been re-released as a special 40th anniversary DVD.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: TV critic David Bianculli on AMC's "Breaking Bad"

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm David Bianculli, TV critic for TVworthwatching.com,

sitting in for Terry Gross.

Last year the American Movie Classics network set out to expand its horizons

and begin producing and presenting original quality television shows. In

2007, AMC presented Robert Duvall in "Broken Trail," the best Western

miniseries since "Lonesome Dove." AMC also presented "Mad Men," an ad agency

drama set in 1960 that ended up on many TV critics' end of year top 10 lists,

including mine. And now, this Sunday, comes another boldly,

against-the-grain, attention-getting offer. This one is called "Breaking

Bad." It's either a very black comedy or a very twisted, funny drama. After

watching three episodes, I'm still not sure which.

What I am sure about, though, is that "Breaking Bad" is a new series well

worth sampling. It stars Bryan Cranston, the exasperated husband from

"Malcolm in the Middle," as Walter White. He's a high school chemistry

teacher who lives in New Mexico and doesn't exactly have it easy. He

moonlights after school at a car wash to help pay the bills and his wife

re-sells flea market junk on eBay, but that's not enough. They have a teenage

son, a good natured kid with cerebral palsy, and a baby on the way. Walter's

wife marks his 50th birthday by presenting him with a special breakfast: a

plate of scrambled eggs with the numbers 5-0 spelled out with strips of veggie

bacon.

Walter might be ripe for a midlife crisis, but he soon learns, as do we, that

midlife has long since passed him by. He's diagnosed as having inoperable

lung cancer and given two years to live, tops. But even before he gets that

bad news, he confronts death on a regular basis, in the classroom during his

chemistry lectures.

(Soundbite of "Breaking Bad")

Mr. BRYAN CRANSTON: (As Walter White) Chemistry! It is the study of what?

Anyone? Ben?

Unidentified Actor: (As Ben) Chemicals.

Mr. CRANSTON: (As Walter White) Chemicals! No! Chemistry is--well,

technically, chemistry is the study of matter. But I prefer to see it as the

study of change. Now just--just think about this. Electrons, they change

their energy levels. Molecules, molecules change their bonds. Huh?

Elements, they combine and change into compounds. Well, that's--that's all of

life. Right? I mean, it's just the constant. It's the cycle. It's

solution, dissolution, just over and over and over. It is growth, then decay,

then transformation. It is fascinating, really.

(End of soundbite)

BIANCULLI: When Walter does learn about his cancer, he doesn't tell his wife

or anyone else. Instead, he has what might be considered a chemical reaction

and begins seething from within. Eventually he has an inspiration and decides

to team up with a local drug dealer and use his scientific expertise to become

the biggest crystal meth manufacturer in Albuquerque.

When I first heard about "Breaking Bad," that was where I grew skeptical. It

sounded too much like "Weeds," the Showtime comedy starring Mary-Louise Parker

as a suburban pot dealer. Also, a crystal meth cooker held little interest

for me as a dramatic protagonist. But Vince Gilligan, the writer, director

and creator of "Breaking Bad," will surprise you if you let him. He did the

same thing for years as a writer-producer on "The X-Files," including one

episode from 1999 which featured Bryan Cranston as the guest star. When

Gilligan began writing "Breaking Bad," he was sure Cranston could fill the

bill both comically and dramatically, and he does.

The two deserve equal credit for pulling off his very improbably trick of a TV

series. Cranston gets credit for making Walter sympathetic, even when you

know you should be rooting against him. And Gilligan gets credit for

confounding expectations at every turn. You know how bad things were for

Walter before he decided to provide for his family by cooking up batches of

crystal meth? Well, things get so much worse for Walter and so quickly that

you don't know how or if he's going to escape from the corner he's been

painted into.

Sunday's premiere episode of "Breaking Bad" got my attention, and the next two

episodes sent for preview won me over, as subplots and supporting characters

rose to the surface. Maybe I shouldn't be surprised, since it's a comedy

drama about crystal meth, but "Breaking Bad" already has me hooked.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Filler: By policy of WHYY, this information is restricted and has

been omitted from this transcript

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Review: Film critic David Edelstein on "Cloverfield"

DAVID BIANCULLI, host:

The new film "Cloverfield" is about a giant monster running amok in New York

City. It has a relatively low budget, a cast of unknowns, and is directed by

Matt Reeves, co-creator of the TV series "Felicity." Film critic David

Edelstein has a review.

Mr. DAVID EDELSTEIN: It has been a decade since the release of "The Blair

Witch Project," which was shot with one video camera from the point of view of

the character holding it. The movie proved that when you eliminate the

omniscient perspective, when you show the audience only what a single

character sees and no more, you introduce a note of irrational terror that

millions of dollars of computer generated effects can't touch. "Blair Witch"

was a ghost story, though, a genre in which less is always more.

What if you used the same vantage for a giant monster picture, a spectacle,

"Godzilla" through the eyes--or lens--of a person way down below trying not to

get stomped? That was the hook of a script by Drew Goddard, which producer

J.J. Abrams snapped up and turned into "Cloverfield." Why the name

"Cloverfield"? It's suppose to be the Army code word for the monster, but

it's really an in-joke. As with "Blair Witch," the buzz was generated by a

so-called viral Internet marketing campaign. And the fans' incessant prying

led the filmmakers to refer to their project by the name of a street outside

Abrams' West Hollywood office. The non-title seemed somehow appropriate and

stuck.

So finally we come to the film, which centers on a bunch of attractive

20-somethings at a part in a Lower Manhattan loft for Rob, who's taking a job

in Japan and leaving behind Beth, the old friend he can't bring himself to

tell he adores. To document the festivities, Rob's brother Jason and

girlfriend Lily thrust a digital video camera into the hands of Hud, a

loveable loser with a crush on a dark-eyed beauty named Marlena, who couldn't

find him more boring.

Hud walks around for a long time sticking his camera in people's faces, and we

wait, semi-bored but with a tingling sense of anticipation. We listen beyond

the party chatter for sounds of oncoming catastrophe. And when it comes,

boom, the party-goers gather in front of the TV set.

(Soundbite of "Cloverfield")

(Soundbite of screaming)

Unidentified Actor #1: Beth! Beth!

Unidentified Actor #2: Did you feel that? It's like an earthquake.

Unidentified Actor #3: You guys...

Actor #1: Beth, where are you?

Actor #3: ...what was that?

Unidentified Actor #4: Who is that?

Actor #1: Hey, are you all right?

Actor #4: Yeah. It was really scary.

Actor #1: I know...(unintelligible).

Actor #4: Yes.

Unidentified Actor #5: Hey, Marlena. Marlena, are you OK?

Actor #2: Guys, we got...

Unidentified Actor #6: Turn on the TV.

Unidentified Actor #7: OK.

Actor #6 All right, here we go. Here we go. Here we go.

Unidentified Actor #8: Oh, wait.

Actor #6: Everybody quiet down. Here we go.

Unidentified Actor #9: You all right?

Unidentified Actor #10: But now...(unintelligible)...

Unidentified Actor #11: Shut up. Shut up. Shut up.

Actor 6: Guys, come on.

Unidentified Actor #12: Sh.

Actor #10: ...approximately 15 minutes, after word of a possible earthquake

in lower Manhattan, nearby in New York Harbor, we're getting word of an oil

tanker capsizing in the middle of the harbor...

Unidentified Actor #13: Oh my God.

Actor #10: ...near the Statute of Liberty. Once again...

(End of soundbite)

Mr. EDELSTEIN: Weaving soap opera problems in and out of apocalyptic carnage

is always a challenge, as the...(unintelligible)...director Roland Emmerich

proved in his "Godzilla" remake and "The Day after Tomorrow." But

"Cloverfield" mostly gets by because the personal can't not be in the

foreground. Rob is determined to get to midtown to rescue Beth. Marlena and

Lily and Jason tag along, and all of them are captured on video by Hud, who

takes seriously his responsibility to document the crisis and whose shooting

is bracingly un-Hollywood-like.

The actors are appealing, although at a certain point I wish Beth gave us more

of a reason to want to see her rescued than a pair of great legs. Still, if

Rob and the others fled Manhattan at the outset, this wouldn't be much of a

movie.

As they make their way toward midtown, the head of the Statue of Liberty flies

into the street, tanks roll by, the sky is lit by yellowish smoke, buildings

collapse in huge clouds of dust. We see the great reptilian beast for only

brief instance, via a swerving camera, which means our imagination fills in

the rest. No scientist explains where it has come from. A government

experiment? An underwater chamber? To make matters worse, it didn't come

alone. It shakes off spider-like parasites that rip people up and infect

survivors with something deeply icky.

Of course, the notion of Hud picking up his camera after a bloody parasite

attack on the group is more improbable than a giant monster flattening

Manhattan. And the kid in you might crave a more objective view of the

creature, not to mention the catharsis that comes from watching science and

the military collaborate on bringing the monster down. That said, we have

seen that monster movie again and again, and we haven't seen anything with

"Cloverfield"'s subjective sting.

The devastation of Manhattan inevitably invokes 9/11, the limited vantage an

easy way for the filmmakers to exploit our newly stoked imaginations of

disaster without bothering about context. So "Cloverfield" is a shallow

exercise, but you'd have to be tougher than I am not to be blown sideways by

it.

BIANCULLI: David Edelstein is film critic for New York Magazine.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.