Edward Snowden Speaks Out: 'I Haven't And I Won't' Cooperate With Russia

In 2013, Edward Snowden was an IT systems expert working under contract for the National Security Agency when he traveled to Hong Kong to provide three journalists with thousands of top-secret documents about U.S. intelligence agencies' surveillance of American citizens.

Guest

Contributor

Related Topics

Transcript

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.

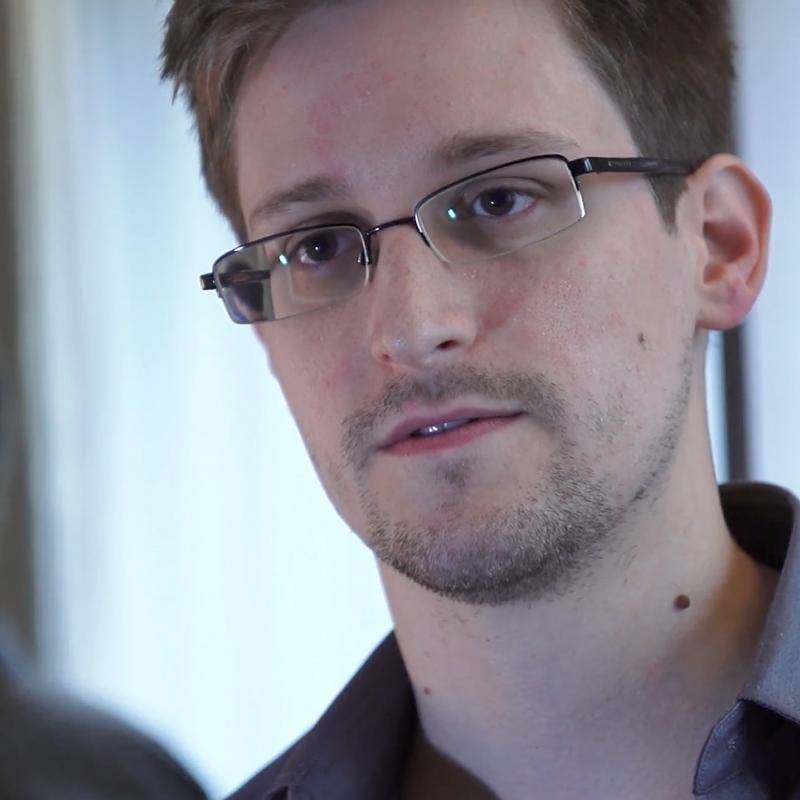

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. To privacy advocates, our guest, Edward Snowden, is a hero, a whistleblower who exposed abuses by government intelligence agencies. To others, he's a traitor who exposed national security secrets. Snowden was an IT systems expert working under contract for the National Security Agency in 2013 when he provided three journalists with thousands of top-secret documents about U.S. intelligence agencies' surveillance of American citizens.

The revelations made Snowden a wanted man accused of violating the Espionage Act. They also led to changes in the laws and standards governing U.S. intelligence agencies and the practices of U.S. technology companies, which now encrypt much of their Web traffic for security.

Snowden has lived for the past six years in Russia out of reach of American law. He's written a new memoir about his life and his experiences in the intelligence community. It's called "Permanent Record." Snowden spoke to FRESH AIR's Dave Davies via an Internet connection from Snowden's apartment in Moscow.

DAVE DAVIES, BYLINE: Well, Edward Snowden, welcome to FRESH AIR. I want to begin with the suspicion that some have that you are a tool of the Russian government or collaborating with Russia. I know that you ended up in Russia stranded at the airport because you had released these documents to journalists in Hong Kong and had booked a flight to Quito. But after the first leg in Moscow, your passport was invalidated by the U.S. State Department, so you got stuck in Moscow. You met a Russian intelligence operative, you believe, at the airport that day in 2013. What was the conversation like?

EDWARD SNOWDEN: You have to remember that I worked for the Central Intelligence Agency. I'm very skeptical of every intelligence service at this point in my life. I've just worked with journalists to reveal mass surveillance. Now, I know - again, having been trained at the CIA, you know, how to get through customs, what an interdiction at passport control looks like - very much what to expect if anybody's up to no good.

And so the main thing is to survive getting through Russia en route then to Cuba, Venezuela and onto Ecuador. You have to travel through non-extradition countries, build a kind of air bridge to get one destination to the other from Hong Kong because every direct flight from Hong Kong to Ecuador goes over U.S. airspace, right? So they can bring you down over California, which is a very problematic thing to be vulnerable to for a person in my position.

So what I wasn't expecting was that the United States government itself, as you said, would cancel my passport. So I'm stopped at passport control. And there's this - you know, the standard passport officer. And when I go through the line, he takes a little bit too long. He picks up the phone. He makes a call. And I realize it's longer than everybody else. And suddenly he looks at me and just says, there is problem with passport. (Laughter) You know? Come with.

And so I'm led very quickly into this business lounge, (laughter) which is very much not standard. Normally you'd be taken off to a security area. And I go in, and it's a room full of Russian guys in business suits. And unmistakably, there's the old guy. He's in charge. And he begins to make what the CIA would call a cold pitch. Now, this is where you have no history, but they try to just say, do you want to cooperate with us?

Now, this is a very unusual situation to be in for an intelligence officer because these kind of pitches, requests for cooperation, are almost always made clandestinely. They're made in private where they can be denied. And the first thing I'm thinking about - because every alarm bell in my head is ringing - is, are they recording this? Are they using this to try to blackmail me, to coerce me? And so, immediately, I go, look, I worked for the CIA. I know what this is. I know what this - how this is supposed to go. This is not going to be that kind of conversation. I'm not going to cooperate. I don't have any documentation with me.

And this is something that publicly is not very well understood. But I destroyed my access to the archive. I had no material with me before I left Hong Kong because I knew I was going to go - have to go through this complex, multi-jurisdictional route.

And so this was the moment where they tried. And he was basically saying, look, is there anything you can do? Is there any small piece of information, anything you share? Because life is going to be very difficult for a person in your situation if you don't have friends. No thanks. You know, great, but I'm not interested. I'll be fine on my own. And then they get up, and they say, I hope you won't regret your decision. (Laughter) It was a little bit of a sinister moment. And then they walk out.

DAVIES: So you've declined their - the Russian intelligence request to cooperate then. You got stuck in the airport for 40 days because you didn't have a passport. They eventually grant you temporary asylum, right?

SNOWDEN: That's correct. And I actually - just to drill in there a little bit, (laughter) you said something very important, which was that I was trapped in that airport for 40 days. Again, for those people who might be a little bit skeptical of me, if I had cooperated with the Russian government - right? - if you think I'm a Russian spy - I would have been in that airport for five minutes before they drove me out in a limo, you know, to the palace where I would be living for the rest of my days before they, you know, throw the parade where they call me a hero of Russia.

Instead, I was trapped in this airport for 40 days, where, instead of saying, you know, Russia, please let me in, I applied for asylum in 27 different countries around the world - places like Germany, France, Norway - that I thought the U.S. government and the American public would be much more comfortable with me being there. And yet, we saw something extraordinary happen, just one thing, which is that the U.S. government worked quite hard to make sure I didn't leave Russia, to the point that they actually grounded the presidential aircraft of the president of Bolivia, which is like grounding Air Force One. It's something that's really unprecedented in diplomatic history.

And it's very much an open question today. Why did the U.S. government work so hard to keep me in Russia? We don't have a clear answer, and we may never have that until more people in the Obama administration start writing memoirs. But it's either they panicked, or they realized this would be an evergreen political attack where they could just use guilt by association, people's suspicion of the Russian government, to try to taint me by proxy.

DAVIES: You say in the book that you applied for asylum to, I believe, 27 countries. Was Russia one of them?

SNOWDEN: At the very end, yes.

DAVIES: There's a sort of a circumstantial case of suspicion, right? I mean, since this happened in 2013, we've seen, you know, the Russian interference in the U.S. election, its collaboration, according to the Mueller report, with WikiLeaks and getting stolen emails to affect the election. And I think there's just a general belief that in this authoritarian state, Edward Snowden wouldn't be able to live for six years unless he were useful to the Russian government. What's the general answer to that?

SNOWDEN: Yeah. I think this is for a lot of people who have sort of a Hollywood understanding of how international affairs and intelligence works. But the reality is, even in the case of, as you said, electoral interference in the case of WikiLeaks, the Mueller report, the United States government itself never alleges that, for example, WikiLeaks even knew that they were talking to Russian intelligence. WikiLeaks' entire system is designed so they don't know who is submitting documents. And even granting that they came from Russian intelligence, that that was in fact the case, every newspaper in the world thought these were newsworthy stories. The New York Times, the Washington Post - everybody was reporting on this.

When you look beyond the sort of the standard examples that we look at in the case of electoral interference, and we look toward my case, there is that question - if, you know, he's not cooperating with the Russian government, why would he be allowed to stay? And I think the answer here is actually quite obvious. Russia doesn't need to do anything - or rather, the Russian government doesn't need to do anything to look good in this circumstance. It shows that they have an independent foreign policy to their public because I applied to all these other countries in Europe for asylum, and all of their governments, unfortunately, could be threatened to revoke their expressions of support.

And this happened - this is a long and well-reported campaign - where every time a country started to lean towards letting me in, it would be either the secretary of state or the then-vice president of the United States that would call their foreign ministry and say, look; if you let this guy in, we're going to retaliate. And Russians very much consider themselves to be a European country. So if the rest of Europe is afraid to do something and Russia is not afraid to do something, that makes Russians feel good.

And remember we did this in reverse to Russia and the Soviet Union for the last 50 years. So of course, if we have an example or an instance where the whole world sees basically the United States government is not living up to its values, the Russian government is going to be very eager just to underline that. That's all they need.

DAVIES: Do you receive any financial support from the Russian government?

SNOWDEN: (Laughter) No, no. This is one of the things that, again, is a common misconception. People sort of think about my life, they think I'm living in, like, a bunker; there's Russian guards; you know, the Russian government and I have any contact whatsoever; they're paying me. No, I have my own apartment. I have my own income. I live a fully independent life. I have never and will never accept money or housing or any other assistance from the Russian government.

DAVIES: We're speaking with Edward Snowden. His new memoir is called "Permanent Record." We'll continue our conversation after a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR, and we're speaking with Edward Snowden, who worked for several years in the U.S. intelligence community. In 2013, he provided top-secret documents about U.S. surveillance of American citizens to three journalists, which resulted in his indictment on alleged violations of the Espionage Act. He's written a new memoir called "Permanent Record." He spoke to us from his apartment in Moscow.

You didn't exactly have a typical adolescence. You ended up spending nights on the computer, school not of great interest to you (laughter).

SNOWDEN: (Laughter).

DAVIES: You tell the story of looking at the website of the Los Alamos National Laboratory that did all this nuclear research and discovering that anybody with a little understanding of computers and directory systems could get internal memos. You looked at confidential memos that were just available. You called the general number at the lab and left a message and said, this is a problem. You eventually got a call back. Tell us about that.

SNOWDEN: (Laughter) So my mother gets a little bit of a rude awakening because she's making dinner, and I'm sitting in the living room on this computer. And she picks up the phone and says, yes, yes, he's here. And she turns and looks at me. And as I see her hearing the other side of the call that I can't hear, her face just gets pale. And she looks at me, and her eyes grow wide. And she covers the receiver and she says, what did you do?

And when I get up out of my chair and I pick up the phone and this this man says, I'm from Los Alamos Nuclear Laboratory, these were the sweetest words anyone could have told me in the moment because I'm like - oh, thank God - because I had left that message, because I had called them, because I hadn't really done anything wrong, I had simply been curious. And as a Boy Scout, I had called this facility and said, hey, there's something broken on your website; you should do something about that.

My mother did not punish me for this. In fact, she was very proud of the fact that I told them they had a weakness in their website. And Los Alamos, for all things, once they realized I was a child - I think they had been expecting someone older - they said when I turned 18, I should give them a call.

DAVIES: You wanted to use your skills. Your skills were in the area of computers. And you get your way into the intelligence - find your way into the intelligence community. You know, critics belittle you as saying you were just a private contractor. I mean, you did work as, actually, a CIA employee for a period of time. But you worked for a lot of private contractors working for the NSA and the CIA. You want to just explain the role of private contractors in the intelligence community?

SNOWDEN: There are congressionally mandated limits on the head count for executive agencies such as the NSA, such as the CIA. And so no matter how much money they get in their budget - and we all know it goes up year after year after year, no matter what - they have to work very hard to get additional head count to hire more people.

So what these intelligence agencies - and really, the defense industry in general - came up with was if they can just shake down Congress for a little bit more money each year, they can actually give this money to private companies - defense contractors, as we now know them - which can then send their personnel, who on paper will work for a Dell or a Lockheed Martin or a Booz Allen Hamilton. On paper, they work for a private company. But in reality, they go into NSA headquarters, the CIA headquarters.

And so the reality is today - people don't realize it - but the work of government, the work of intelligence is as frequently performed by employees of private companies as it is performed by military or government personnel.

DAVIES: You had a lot of jobs in the intelligence community. You were actually a CIA officer in Geneva for a while. You ended up in Tokyo after that and then Hawaii. And you write that the material that you distributed to journalists ultimately documented an array of abuses so diverse that nobody was ever in a position to know all of them. To really to found out even a fraction, you had to go looking. And what set you looking was an assignment to do a presentation about China. You want to explain this?

SNOWDEN: So, yeah, I'm invited to give a presentation about how China is hacking the United States - intelligence services, defense contractors, anything that we have available in the network - which I know a little bit about but not that much about because they have the person who's supposed to be giving the presentation drop out. So I go looking. I use my network access to pull all the slide decks, all of the presentation, all of the training that's previously been given. I pull all of the recent reporting on what's happening, and I work late into the night seeing, what exactly is it that China is doing? What are their capabilities? Are they hacking? Are they doing domestic surveillance? Are they doing international surveillance? What is occurring?

And I'm just shocked by the extent of their capabilities. I'm appalled by the aggression with which they use them but also, in a strange way, surprised by the openness with which they use them. They're not hiding it. They're just open and out there saying, yeah, we're doing this. Yeah, you know, we're hacking you. What are you going to do about it? And I think this is a distinction. I think - yes, the NSA is spying. Of course, they're spying. But we're only spying overseas. We're not spying on our guys at home. We wouldn't do that. We have firewalls. We have tripwires for people to hit. But surely these are only affecting terrorists because we're not like China. But this plants the first seeds of doubt where I see if the capability is there, perhaps somewhere hidden deep even inside the United States government. The appetite for how they can use these capabilities remains the same.

DAVIES: Right. So you explore further, and what do you discover about what the NSA is actually doing?

SNOWDEN: So over the final years of my career, I see that we have the same capabilities as the Chinese government and we are applying them domestically just as they are. We have an internal strategy at the NSA, which was never publicly vowed but it was all over their top-secret internal slides, that said the aspiration was to collect it all. What this means was they were not just collecting and intercepting communications from criminals, spies, terrorists, people of intelligence value. They were collecting on everyone, everywhere all of the time just in case because you never know what's going to be interesting. And if you miss it when it's passing by, you might not get another chance.

And so what happened was every time we wrote an email, every time you typed something into that Google search box, every time your phone moved, you sent a text message, you made a phone call, increasingly, the United States government - without giving the public a vote - we weren't allowed to know this as a public. But in secret, the boundaries of the Fourth Amendment were being changed. This was without even the vast majority of members of Congress knowing about it. And this is when I start to think about, maybe we need to know about this. Maybe if Congress knew about this, maybe if the courts knew about this, we would not have the same policies as the Chinese government.

DAVIES: Right. But to be clear about what you discovered, you're talking about bulk collection of all of these electronic communications, which are then kept for how long and where? I mean, how do they have the capacity for this?

SNOWDEN: So this is a great question. What we're describing largely here is me discovering something called the Stellar Wind program, a classified inspector general report into Bush-era warrantless wiretapping program and what came out of it. Turns out, it wasn't just about phones. It was, as you say, Internet communications. And this is the core difference. It's not phone or Internet. It's targeted versus untargeted.

Historically, the United States intelligence community has only been performing and only been authorized to perform targeted surveillance. You look at a bad guy, you tap their communications. You intercept those communications. You put that in the database. You store. You search it. You do whatever you want. But you know it's...

DAVIES: And you get a court order for it, right?

SNOWDEN: Right. Right. Well - so in many cases, yes, particularly for use in the criminal justice system. But now they've automated and expanded the system so it's not targeted. It's a dragnet that hits everyone everywhere. And this is only happening because for the first time, it's technically possible. It's easy. It's cheap. And because they've secretly co-opted, either through coercion or seduction, the major Internet giants - Microsoft, Apple, Google, Facebook - into sharing their information with the U.S. intelligence community, sometimes through a process of secret court orders, everything is available to them. And they try to store it for as long as they can because they don't know when it's going to be useful. And so as technology progresses, this distance for which they store it becomes close to forever.

One of the NSA's close partners, AT&T, the telecommunications company, stores phone records now for people in the United States going all the way back to 1987. If you've got kids or you, yourself, are born after 1987, they have every phone call that you ever made. They keep the records of your movements of your cell phone, basically, what cell phone tower you're connected to. And, you know, that changes as go driving, as you move throughout the world. They store the movements for everyone on their network that they can going back to 2008. And we expect these to grow - right? Eventually, our entire lives will be in this ever-growing permanent record of human activity.

GROSS: We're listening to the interview FRESH AIR's Dave Davies recorded with Edward Snowden. He's written a new memoir called "Permanent Record." After a break, they'll talk about why Snowden decided to go to journalists with classified documents about government surveillance and what conditions he imposed on their use of the material. And he'll explain the circumstances under which he would return to the U.S. to face charges that he violated the Espionage Act.

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Let's get back to the interview FRESH AIR's Dave Davies recorded with Edward Snowden, a former IT systems manager who worked under contract for the National Security Agency. In 2013, he gave three journalists access to thousands of classified documents describing U.S. intelligence agencies' surveillance of American citizens. Snowden spoke to Dave through an Internet connection from his apartment in Moscow.

DAVIES: So now you're a guy who believed in the U.S. intelligence services. You were the son of two career government servants. When you discover this broad surveillance, what impact does it have on you emotionally?

SNOWDEN: It was astonishing sense of violation because think about it. You know, people look at me now. And they think I'm this crazy guy, I'm this extremist - whatever. Some people have a misconception and think I set out to burn down the NSA. But that's not what this was about. In many ways, 2013 wasn't about surveillance at all. What it was about was a violation of the Constitution. What it was about was democracy and government. I had signed up to help my country.

On my very first day entering into duty for the CIA, I was required to pledge an oath of service. Now, a lot of people are confused. They think there's an oath of secrecy. But this is important to understand. There's a secrecy agreement. This is a civil agreement with the government, a nondisclosure agreement called Standard Form 312 - very exciting - that says you won't talk to journalists. You won't write books, as I have now done.

But they - when you give this oath of service, it's something very different. It's a pledge of allegiance not to the agency, not to a government, not to a president, but to support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies foreign and domestic. And so when I realized we have been violating, in secret, the Fourth Amendment of that Constitution for the better part of a decade - and the rate of violation is increasing. The scope of the violation is increasing with every day. We are committing felonies in the United States under a direct mandate from the White House billions of times a day. Honestly, I fell into depression. And this leads to a period where I resign from what would be considered direct mission-related work out in Japan - in the foreign field, as we call it. And I return to a purely corporate position for Dell as a sales official at CIA headquarters.

DAVIES: Before you actually go through the revelations of this material, you described going to Fort Meade, the NSA's headquarters. And you see analysts using a tool that allows them to exploit the fruits of all this mass surveillance. It's a tool called XKeyscore. What did it allow these guys to do...

SNOWDEN: OK. So...

DAVIES: ...Allow you to do?

SNOWDEN: So when you think about all of these intelligence programs you've heard of - right? - they've got your email. They've got your Internet communications. They've got your phone calls. But for everybody everywhere - obviously, this isn't just a straight stream. People aren't reading it as it comes in because it would take more hours in the day. I think, you know - any government has people to go through.

So what they actually do is they just dump this into gigantic data centers, like they've built in Bluffdale, Utah, and other smaller, covert ones around the world so they don't have to move the data around. So they construct what's called a distributed query system - you can think of this like Google for spies. And what it does is - anywhere in the world that we've collected information, everywhere we're intercepting communications now, we have our own little search engine. It's a Google box, that little prompt, that you can access from your desk wherever you are just in an NSA internal website.

And you can type in anybody's phone number, anybody's email address, any computer's Internet address. And then anywhere on the Internet that one of our sensors has collected a communication, it will look through, instantly, everything that it has. And then it will send just the results back to that employee. So you can spy on anyone in the world from anywhere in the world as long as you have access to this network and this tool.

DAVIES: So if you have the clearance, you pick a name, you get their phone calls, their Web searches - what?

SNOWDEN: Yeah. So I'm working with the Internet side of it. We have people who work with telephony data, which is largely phone calls and SMSes (ph). But your Internet data - it is everything, largely, that transit the global communication network. If you send it over a satellite hop, we have what are called foreign sat - foreign satellite sites - all over the world that are just listening to the sky.

If you are sending it to a cellphone tower, well, we hack those all over the world to the best of our ability. If you send it over a landline - right? - your fiber-optic cable at your home - and that goes to your Internet service provider, well, your Internet service provider probably cooperates with the NSA through the FBI.

And this is being replicated again and again and again throughout the country and across the world. It's not everywhere, but it's as close to everywhere as we can get. And this means it's basically every communication that can be intercepted, that can be stored, that can be processed, that can be decrypted. We can search, and we can read.

DAVIES: You set up one of these terminals and had access to this. And you described looking at the material of a professor in Indonesia, right?

SNOWDEN: Yeah. So this is an academic. He is just some kind of engineer. I believe he's applying for either a position or a period of study at a university in Iran. And the U.S. government, for whatever reason, has an interest in this particular university. We don't spy on every university. But we spy on, interestingly, a lot of them, which would surprise people. But it is Iran, so people go, OK. You know, maybe there's some intelligence value. Maybe this guy's a terrorist.

And what struck me here was that normally when we do a deep dive and we look into someone, it's because they're up to no good. It's because they're associated with terrorism. This gentleman, in fact, was not. He's applying to a university, but he's caught up in the dragnet. And so they have his university admissions application. They have pictures of his passport.

And then I see something unusual; something that I don't normally see. I see a video file. Now, we can intercept video files just like we do with everything else. But this one, to me, indicated that it was produced because we had hacked his machine. And we had turned his webcam on while he was at the machine. And we do this sometimes to confirm - particularly infrastructure analysts - who at this anonymous machine is actually using it to find...

DAVIES: So he's on his laptop, right?

SNOWDEN: Yes, he's on his laptop. And we're looking at the man behind the device. And in his lap is a little boy, a toddler, who's just playing on the keyboard. And the father's smiling. And the little boy looks at the webcam. It's just a glimpse, but to me it seems as though he's looking at me. And it reminds me of my childhood, of learning about technology with my own father. And I realize this man has done nothing wrong. He's just trying to get a job. He's just trying to study. He's just trying to get through life like all of us are. And yet, he's caught up. His children are caught up. We are all caught up by a system that we were not allowed to know existed. We were not allowed to vote whether this was proper or improper, and courts were not allowed to assess - open courts, real courts - whether it was proper and constitutional. Where do we go from there?

DAVIES: Edward Snowden's new memoir is called "Permanent Record." We'll continue our conversation after a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF AMANDA GARDIER'S "FJORD")

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR, and we're speaking with Edward Snowden, who worked for several years in the U.S. intelligence community. In 2013, he provided top secret documents about U.S. surveillance of American citizens to three journalists, which resulted in his indictment for allegedly violating the Espionage Act. He's written a new memoir called "Permanent Record." He spoke to us from his apartment in Moscow.

So I want to talk about your decision to release this access to many documents to three journalists and just talk about why you took the course you did and why some critics say you had other options. One thing people say is, look. There's a system. There are Inspector Generals' offices of each of these agencies. Why couldn't you go to them?

SNOWDEN: Well, this is a great question. For one, we've never seen the Inspector General's office actually be an effective safeguard for the Constitution itself. We have had, since I came forward, one of the Inspector General employees - I believe the Deputy Inspector General for the NSA - come forward and say, if Snowden had come to me, I would have explained to him his misconceptions about how these programs worked, how these things are, in fact, legal, how these things are, in fact, constitutional, and maybe he wouldn't have had to do this at all.

The Inspector General is a great resource to have if someone is a middle manager and they're engaged in sexual harassment or they are embezzling or something of that nature. But if you have a criminal conspiracy inside not just the leadership of the NSA but, in fact, in the White House that is run by the vice president's own lawyer in the Bush administration - Dick Cheney had a lawyer named David Addington who said building this mass surveillance system in the very first instance was legal when, in fact, he knew that was not the case - what do you do? This is asking you, the hens, to sort of report the fox's misbehavior to the fox himself.

And I want to point out just real quickly that it's not in contention that these programs were illegal, that these programs were likely unconstitutional. That's not my assertion. That is the assertion of the very first federal court. I think a ruling of Judge Leon in the wake of these disclosures prior to the revelations of mass surveillance in 2013 - the government, A., said these things weren't happening; B., if they were happening, they were legal; and C., why are you even asking about this in the first place?

DAVIES: The description in the book of how you worked through how you were going to release this material and how you contacted the journalist and provided it is really fascinating. We won't have time to go into it here, but I want to talk to you about some of the specific arrangements you made. Three journalists were provided with access to thousands of documents that you had. What conditions did you impose on their use? What did you tell the journalists about what they could do and not do?

SNOWDEN: When we look at what happened, what produced this, the system of checks and balances failed. And so if I had come forward myself and said, look. This is wrong. This is a violation of the Constitution. I'm the president of secrets, and I'm going to decide what the public needs to know. I just throw it out on the Internet - which wouldn't be hard for me. I'm a technologist. I could have done this in an afternoon. There's a risk implied in that. What if I was wrong? What if I didn't understand these things? What if it was, in fact, legal or constitutional, or these programs were effective rather than, as I believed, ineffective - which later was confirmed by the Obama administration these programs weren't saving lives. They had some intelligence value, but they didn't have a public safety value, at least that was meaningful.

So what I did was I tried to reconstruct the system of checks and balances by using myself to provide documents to the journalists but never to publish them myself. People don't realize this, but I never made public a single document. I trusted that role to the journalists to decide what the public did and did not need to know. Before the journalists published these stories, they had to go to the government - and this was a condition that I required them to do - and tell the government, warn them they're about to run this story about this program. And the government could argue against publication - say, you've got it wrong, or, you've got it right - but if you publish this, it's going to hurt somebody. In every case I'm aware of, that process was followed, and that's why, in 2019, we've never seen any evidence at all presented by the government that someone's been harmed as a result of these stories.

That's why, I believe, these stories won the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service. It's because there is a way that you can maximize the public benefit of a free press and them aggressively contesting the government's monopoly on information, at the same time mitigating the risks of even a very large disclosure of documents by simply making sure that you trust the right people, the right sector of society, with the right system to keep everyone honest because all of us work better together than we do alone.

DAVIES: You know, I will say that, on that question of whether this has put - harmed American interests or put people in danger, there was an AP story last year, it was - quoted as spokesman for the National Counterintelligence and Security Center as saying Snowden's disclosed documents have put U.S. personnel or facilities at risk around the world and damaged intelligence collection efforts, exposed tools used to amass intelligence, etc. Are they wrong?

SNOWDEN: They are wrong. Look. I can't correct six years of lies, you know, in 60 seconds. But when you look at all of those claims, they're always merely allegations. The government has never put forward any evidence. And they have investigated me for six years; so has basically every other government on the planet. And you, a journalist, know better than anyone else that the government aggressively leaks when it's in its favor. You can look at this White House right now. If these kind of - if disclosures of classified information, just hard stop, caused damage - if they created risks for U.S. personnel or programs, three-quarters of the White House would be in prison right now. They're not because the vast majority of leaks - while they are uncomfortable, while they are embarrassing or sometimes beneficial to government - far more is classified than actually needs to be.

So yes, the government has made those allegations, and they will continue to make those allegations. But look; the thing that we always have to ask is, what is the evidence to back that assertion? And they've never provided that, and I'm quite confident they never will because it didn't happen.

DAVIES: We're speaking with Edward Snowden. His new memoir is called "Permanent Record." We'll continue our conversation after a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR, and we're speaking with Edward Snowden, who worked for several years in the U.S. intelligence community. In 2013, he provided top-secret documents about U.S. surveillance of American citizens to three journalists, which resulted in his indictment on alleged violations of the Espionage Act. He's written a new memoir called "Permanent Record." He spoke to us from his apartment in Moscow.

You fully expected to be identified. You eventually identified yourself to explain your motives. As you were planning this, what kind of future did you envision for yourself?

SNOWDEN: The likeliest outcome for me, hands down, was that I'd spend the rest of my life in an orange jumpsuit. But...

DAVIES: In prison.

SNOWDEN: Yes. But that was a risk that I had to take.

DAVIES: So now you're - you've been in Moscow for six years. Lindsay Mills has joined you. You are now married. You live in a two-bedroom apartment. What kind of security precautions do you take? You didn't want to go to a studio for this thing - for this interview. Right? You're pretty careful, aren't you?

SNOWDEN: Yeah. Well, I run my own studio because, you know, people ask how I make my living. And (laughter) I give lectures. I speak publicly for the American Program Bureau, and places book me to speak about the future of cybersecurity, what's happening with surveillance and about conscience and whistleblowing.

But I do - you know, I've never been the nightclub type. I'm a little bit of an indoor cat (laughter). Whether I lived in Maryland or New York or Geneva or Tokyo or Moscow, I'll always spend the majority of my time looking into a screen. So yeah, while I'm out on the street, I try not to be recognized. I also live a much more open life now than I did back in 2013 because it seems - the consensus has resolved that (laughter) anyone who tries to kill me is only going to prove my point.

DAVIES: Do people ask you for selfies?

SNOWDEN: (Laughter) Usually, I get that when I'm identified because I'm meeting journalists at a hotel or something. Out on the street, almost no one recognizes me, which, to a privacy advocate, is just the most wonderful gift that you can get. I do get noticed sometimes, like when I go in computer stores. Or if - I went in a museum once; some Germans seem especially good at identifying me. I'm not sure why. Maybe it was how I was covered in media. But they asked for selfies, and of course I'm happy to provide them.

DAVIES: I mean, you say in the book that you try to go out with a hat on; you might change your beard. Why do you not want to be recognized? What do you fear?

SNOWDEN: Well, think about it. I mean, you work in media. You're a journalist. You make your living from talking not just publicly but talking to people who have interesting things to say. And yet, you don't put your address (laughter), I think, on your website so fans can just show up at the door.

Now, we all have a desire for a certain level of privacy. I think I have risks that are higher than the average person. But even if I didn't, I would rather be able to selectively share information with people about where I live, how I live, how I spend my time and, honestly, who I am.

DAVIES: Fair enough. I guess I'm just wondering...

SNOWDEN: I would rather just be the anonymous person. Why not?

DAVIES: I guess I'm just wondering, do you expect - do you think someone might try and kidnap you and extradite you to the United States or that, you know...

SNOWDEN: Well, if that's been the plan, they've done a really poor job at it, since six years later, I'm still free. I would like to think, on the part of my government, that they're not that far gone and they're not actually looking to disappear whistleblowers. Or perhaps it's just simply because it's too difficult when I'm on the other side of the world and in, no less, Russia. But I don't worry as much as I did; maybe it's fatigue. But yeah, there was a period where I didn't want to go out (laughter) without shaving. There was a time when I didn't want to go out without putting a scarf and a hat on.

But those days for me are long gone. The book ends back in that period. And the beautiful thing about life and about, I guess, the story that I've been fortunate to live is that even when things get as bad as they possibly can, even when you see all of the ways the system can fail, time and people always have the chance to make it better.

DAVIES: As somebody who knows a lot about the kind of information that can be gleaned from a cellphone, I'm wondering what precautions you take with your own cellphone use?

SNOWDEN: Well, first off, I try not to use one as much as possible. And when I do use one, I use a cellphone that I've myself modified. I perform a kind of surgery on it. I open it up with special tools, and I use a soldering iron to remove the microphone, and I disconnect the camera so that the phone can't simply listen to me when it's sitting there. It physically has no microphone in it. And when I need to make a call, I just connect an external microphone through the headphone jack, right? And this way the phone works for you rather than you working for the phone.

You need to be careful about the software you put on your phone. You need to be careful about the connections it's making because, today, most people, they've got a thousand apps on their phones. It's sitting there on your desk right now or in your hand, and the screen can be off, but it's connecting, you know, hundreds or thousands of times a second. If some of your audience is listening to this on podcasts right now through, for example, earbuds, they know their screen can be turned off. They can be sitting, riding in their pocket along with them. They don't even have to be looking at the phone, but it's still very much active.

And this is this core problem of the data issue that we're dealing with today. We're passing laws that are trying to regulate the use of data. We're trying to regulate the protection of data. But all of these things presume that the data has already been collected. What we need to be doing is we need to be regulating the collection of data because our phones, our devices, our laptops, even just driving down the street with all of these systems that surround us today, is producing records about our lives. It's the modern pollution. It is invisible, but it still harms us. But it doesn't harm us for some years.

DAVIES: Let me ask you one other question. You've lived in Russia for six years now. Do you see yourself making a life there or do you hope to come home someday?

SNOWDEN: My ultimate goal will always be to return to the United States. And I've actually had conversations with the government, last in the Obama administration, about what that would look like. And they said, you know, you should come and face trial. And I said, sure, sign me up, under one condition. I have to be able to tell the jury why I did what I did. And the jury has to decide, was this justified or unjustified? This is called a public interest defense, and it is allowed under pretty much every crime someone can be charged for. Even murder, for example, has defenses. It can be self-defense and then so on and so forth. It could be manslaughter instead of first-degree murder.

But in the case of telling a journalist the truth about how the government was breaking the law, the government says there can be no defense. There can be no justification for why you did it. The only thing the jury gets to consider is, did you tell the journalist something you were not allowed to tell them? If yes, it doesn't matter why you did it; you go to jail. And I have said, as soon as you guys say, for whistleblowers, it is the jury who decides if it was right or wrong to expose the government's own lawbreaking, I'll be in court the next day.

Unfortunately, the attorney general at the time sent back a letter saying, you know, that that sounds great, but all we can do for you right now is we will promise not to torture you (laughter). So I'd say negotiations are still ongoing.

DAVIES: Although, you haven't actually negotiated since the Obama administration, right?

SNOWDEN: Right, right, right. We're waiting for their call, but the ball is very much in the government's court.

DAVIES: Edward Snowden, thanks so much for speaking with us.

SNOWDEN: Thank you for having me.

GROSS: Edward Snowden spoke to FRESH AIR's Dave Davies from his apartment in Moscow. Snowden's new memoir is called "Permanent Record." Their interview was recorded Tuesday morning. Soon after, the news broke that the U.S. Justice Department filed suit to recover all proceeds from Snowden's book, alleging that he violated nondisclosure agreements by not letting the government review the manuscript before publication. Snowden's attorney Ben Wizner said in a statement that the book contains no government secrets that have not previously been published by respected news organizations and that the government's prepublication review system is under court challenge.

If you'd like to catch up on FRESH AIR interviews you missed - like our interviews this week with New York Times reporters Robin Pogrebin and Kate Kelly about their book "The Education Of Brett Kavanaugh" or Andrea Mitchell of NBC News and MSNBC, who's about to receive an Emmy for lifetime achievement - check out our podcast. You'll find lots of FRESH AIR interviews.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: FRESH AIR's executive producer is Danny Miller. Our interviews and reviews are produced and edited by Amy Salit, Phyllis Myers, Sam Briger, Lauren Krenzel, Ann Marie Baldonado, Therese Madden, Mooj Zadie, Thea Chaloner and Seth Kelley. I'm Terry Gross.