From the Archives: From the Streets to Galleries.

The visual artist Keith Haring emerged when punk and New Wave music and the hip-hop scene of graffiti artists and break dancers were the background and source for music and art appearing throughout New York. His work responded to, and helped form and translate, the city's street culture. He died in 1990 at the age of 31. The Whitney Museum in New York is currently showing an exhibit featuring many his works through September 21. (Originally aired 9/3/87)

Other segments from the episode on July 25, 1997

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: JULY 25, 1997

Time: 12:00

Tran: 072501np.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Kenneth Branagh

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:06

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

On this archive edition, we have an interview with Kenneth Branagh about his film adaptation of "Hamlet," in which he stars as the prince of Denmark. It's just come out on home video.

Branagh has also directed film adaptations of Shakespeare's "Henry V" and "Much Ado About Nothing" and he co-starred in the recent film of "Othello." His Hamlet features English and American actors: Derek Jacoby as Claudius; Julie Christie as Gertrude: Kate Winslett, Ophelia; Robin Williams, Osrick; Jack Lemmon, Marcellus (ph); and Billy Crystal is a gravedigger.

Here's Billy Crystal and Kenneth Branagh in a scene when Hamlet has secretly returned to Denmark. He's walking through the graveyard, and doesn't realize the digger is preparing a grave for Hamlet's lover Ophelia, who has just drowned.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, KENNETH BRANAGH PRODUCTION OF "HAMLET")

KENNETH BRANAGH, ACTOR, AS HAMLET: Whose grave's this sir?

BILLY CRYSTAL, ACTOR, AS GRAVEDIGGER: Mine, sir. Oh, pit of clay for to be made for such a guest as me.

BRANAGH: I think be thine indeed, for thou liest in it.

CRYSTAL: You lie out, odd sir, and therefore it is not yours. For my part, I do not lie in it, and yet it is mine.

BRANAGH: Thou dost lie in it to be in it and say 'tis thine, 'tis for the dead, not for the quick, therefore thou liest.

CRYSTAL: 'Tis a quick lie, sir. Twirl away again, from me to you.

BRANAGH: What man dost thou dig it for?

CRYSTAL: For no man, sir.

BRANAGH: For what woman, then?

CRYSTAL: For none neither.

BRANAGH: Who is to be buried in it?

CRYSTAL: One that was a woman, sir, but rest her soul, she's dead.

BRANAGH: How absolute the knave is -- we must speak by the card or equivocation will undo us. Put a lord, Horatio, these three years I have taken note of it. The age has grown so picked, the toe of the peasant comes so near the heel of the courtier, he gauls his kind.

GROSS: For listeners who've never read Hamlet or seen a production or who have just forgotten, tell us the basic story and in just, you know, plot terms.

BRANAGH: Sure. I'm not sure, you know, that lots of people do know the story of Hamlet, to be perfectly honest. And I certainly approached this film with that in mind. Hamlet is the heir to the Danish throne. His father has died -- poisoned by a serpent in his garden. This happens one month previous to the beginning of the play.

And we meet Hamlet when his mother Gertrude has remarried his uncle. This is one month after his father's death. Hamlet is unhappy about this -- bitterly angry that she should have married so quickly. He is visited by the ghost of his dead father, who tells him that he was murdered and that he was murdered by his uncle and that Hamlet must revenge him.

So Hamlet's problem for the rest of the play is that he, the heir to the throne, has to kill the king -- the reigning monarch -- in order to avenge his father's death. And all the rest of what occurs in the play springs from that one central dilemma for Hamlet.

GROSS: Do you feel like you've brought a new overall vision to this production of Hamlet -- a different interpretation than you've seen in the past?

BRANAGH: I think the way we have produced our vision I hope is different and original. With things like Shakespeare, and Hamlet in particular, I think it's hard to claim any originality. I feel as though everything's probably been done by minds much greater than mine, but we at least in choosing, for instance, to set it in a kind of impressionistic 19th century, in a much more colorful way than is perhaps usually done. Hamlet seems to be perceived as a very dark and Gothic play where all the characters are sort of predisposed to be manic-depressives.

GROSS: That's right.

BRANAGH: I don't believe that from reading the text. Nothing, nothing about what's said in the play gives the idea that under different circumstances, I -- not at a time when the king is just killed -- would they be anything other than very alive and curious and bright.

I think that central sort of change of thought is the, if you like, originality of our view.

GROSS: This Hamlet is -- your production is four hours long and you use the whole text and even, I think, a couple of additions. Whereas when Olivier did his movie version of Hamlet, he cut out a lot of the minor characters -- a lot of the subplots, and shortened it to about half the length.

BRANAGH: Yes.

GROSS: With your production, why did you want to keep everything in, knowing how difficult it is to sell a movie that's four hours long?

BRANAGH: My experience of playing this play in the theater in several productions, including one that was at the full-length, was that the story was easier to follow. Even if people haven't seen or even heard of Hamlet, there is a misty kind of memory of a fellow in black, you know, and holding a skull and being a bit depressed.

GROSS: That's right.

BRANAGH: So they've got some idea of what to expect, and yet they get intimidated by it and they think it will be somebody being very morose and intellectual. Of course, he's a very bright and intelligent man, but there's a story there that is very thrilling.

It has basic elements that Shakespeare's contemporaries used in this genre: the revenge melodrama. If there was a film equivalent, maybe it would be the thriller.

As a form, Shakespeare uses madness, revenge, suicide, the visitation of a ghost, the possibility of incest -- these are all kind of crowd-pleasing, page-turning -- rather, you know, low elements, he might say.

But alongside that, there's a story of many different things: a family crisis; story about miscommunication in a family with which we can all identify, I think. It would be tough if your mother remarried your uncle inside a month of your father's death. That's a tough issue.

But they also are a royal family, so what they do -- the impact of their personal problems is felt across a whole nation. And so you have the end of a dynasty, if you like.

You see a whole world in transition, and you see the very personal problems of people who are in situations that we might find ourselves in, but they have the extra dramatic quality of being watched -- they're under the microscope.

They're people in positions of power whose every move is scrutinized, rather like our own political leaders today; our own royal families today.

And I think that that mixture of something very epic, dealing with the fate of nations and war and politics and something very, very familiar and intimate and domestic and personal is what makes the long version not only easier to follow, but more gripping.

GROSS: We're all taught in English classes that Shakespearian tragedies are about a great person of heroic proportion who is brought down by a fatal flaw. And in Hamlet, well the fatal flaw some people say "oh, it's his depression; it's his indecision."

I had a feeling it was like really self-absorption. You know, watching your Hamlet, I'm thinking: well, Hamlet is so -- just oblivious to how he's destroying Ophelia and how he's treating her; and the way he's tearing apart his mother; and how he's dealing with her remarriage. And he's even oblivious to what this is doing to his kingdom. He's self-absorbed.

BRANAGH: Well, I think that that, for me, makes him very, very recognizable and human.

GROSS: Very contemporary.

BRANAGH: Very contemporary -- self-absorption of individuals this end of the century is pretty astonishing, especially post-Freud and post-all the sort of psychoanalysis that we have as part of our sort of daily bread and butter. It's on television; it's in self-help books in libraries. We're all somehow trying to find ourselves.

Now Hamlet is certainly doing that. In doing the long version, of course, what you get are moments of revelation, including I think a crucial one, which is at the end of the first half of our picture, where Hamlet goes out onto the plain in Norway and sees Fortenbras -- also a young man, also a prince, also just lost his father, also got his uncle on the throne -- who, as distinct from Hamlet, is happy to send off a group of 20,000 men to fight for a piece of Poland which is simply a sort of political expedient, because he thinks it's right.

Hamlet can't do that, and it puts his problems in perspective. He has to go back. He has to face his own problems. At that point, of course, Hamlet has become a murderer -- the self-absorption you so rightly mention has also produced someone who ends up killing the prime minister -- a fact which has been hushed up, but makes Denmark a hotbed of scandal, intrigue, and revolution.

Laertes comes back -- the dead father's son to avenge him. And I think in the long version, you get a sense of Hamlet traveling to a point in his life where perhaps he is seeing a little more outwardly, instead of inwardly. He is learning to forgive a little; be a little more tolerant.

For me, I suppose that's what the story's about -- that there's a point at which it's quite healthy to be looking at yourself; and there's a point at which it perhaps tips over into something unhelpful.

GROSS: I wonder if you like the character of Hamlet? If you think of him as someone you want to -- that you would identify with and admire? Or somebody who is so flawed in some ways that you -- you have real problems with him?

BRANAGH: I do like him. I like him because he is flawed. I like him because of his fallibility. I think that his heroism, if you like, springs from his human frailty. This is a man who is often very cruel, as we mentioned before. He's brutal in his treatment of both Ophelia and Gertrude -- people that he loves.

But my experience of life, such as it is, is that the people are most cruel to those that they love. One of the reasons, I suppose, in the tragic, inevitable scheme of things that Hamlet has to die, is that we know that he has done some things which just, you know, in the grand scheme of things, can't be forgiven.

But he has essentially tried to face up to his problems, I believe -- has tried to work them out. But it's his very complexity -- his contrariness; his contradictory qualities; a man who can appreciate so keenly his friendship with Horatio and the importance of friendship; who can be so loving with Ophelia, on one hand, and then so terrifyingly aggressive with her -- this is somebody I think who is remarkably human and yeah, I think he's somebody I'd like to spend time with.

GROSS: One of the many famous lines that comes from Hamlet is about being cruel to be kind. And he says this to -- I forget whether it's Gertrude or Ophelia...

BRANAGH: He says it to Gertrude.

GROSS: ... and you know, I just -- this is the first time I found myself wondering: is Hamlet so kind of gifted with words that he can rationalize whatever he's doing?

BRANAGH: He, to some extent, may well be a prisoner of a very strong intellect. And when he says that to her, he has just murdered the prime minister, who's lying in a pool of blood in her bedroom. Their lives have changed forever from that point. The prime minister's been killed. The world will change.

GROSS: This is Polonius.

BRANAGH: Yeah.

GROSS: And it's an amazing scene, really -- yeah, he's just -- he sees this figure lurking behind the curtain and kills him, thinking it's probably going to be the king...

BRANAGH: Yeah.

GROSS: ... but it's actually Polonius, who's got his own problems, but Hamlet wouldn't have wanted to kill him. And he's lying there in this big pool of blood, and Gertrude and Hamlet are just, like, talking and talking and trying to work things out -- just kind of oblivious to the fact that there's this bleeding corpse a couple of feet away.

BRANAGH: Well, they're having the conversation, if you like, that they should have had at the beginning of the film when Hamlet really wants to say to her: "how could you be so insensitive as to marry my uncle within one month of my father's death?" So they need to say things that go above and beyond their sensitivity to the fact that they've just killed somebody.

GROSS: My guest is Kenneth Branagh. We'll talk more after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

Back to our interview with Kenneth Branagh recorded in January. His film adaptation of Hamlet has just come out on home video.

There are so many lines from Hamlet that are famous. Run through some of them.

BRANAGH: Well, we have the -- probably the most famous line in English literature: "To be or not to be? That is the question." You mentioned "cruel to be kind," "neither a borrower nor a lender be," "to thine own self be true." You've got "alas, poor Yorick, I knew him, Horatio." I always used to think it was "alas, poor Yorick, I knew him well."

GROSS: Me too.

BRANAGH: Yeah, and that was the kind of thing that I picked up as a kid off the television, 'cause there were all these cliches about Hamlet. So it's full of them.

It's absolutely full of them, as Shakespeare is, but Hamlet in particular is full of quotes that have absolutely worked their way into the language.

GROSS: Give me a sense of one of these quotes that is kind of really worn out when it's used as, like, common wisdom or a great quote out of context -- but really works in context and has a genuinely interesting meaning in context.

BRANAGH: Well, I'll tell you a funny example of it, which is to refer to a line that you mentioned earlier on: "I must be cruel" -- the line in the text is -- "I must be cruel only to be kind" which colloquially becomes "you have to be cruel to be kind" or whatever.

I had boils on my knee when I was about seven or eight years old, and my mother used to squeeze them with hot and could poultice. She claimed there was no other way to deal with this. I've since taken her to task about it.

But that was the line she used to come out with, you know -- "I must be cruel to be kind" as she squeezed these boils and I was seven or eight years in Belfast.

Now that line, you know, in context, is, I have to say, nothing to do with squeezing boils and is -- does express some of what you rightly mention is this -- a certain kind of self-righteousness that Hamlet has from time to time, which is not a very appealing quality, but which is also part of being a human being in a very traumatic situation.

GROSS: Tell me about approaching the "to be or not to be" soliloquy -- the most famous of all soliloquies, perhaps leading with the most famous line in all of theater. What did you think about in order to make that sound meaningful, and not like "oh yeah, those lines -- I know those lines."

BRANAGH: Well, I 'spose there were lots of things to consider. I had played it in the theater many times, and found it difficult. You come on sometimes -- I'd seen actors do it, actually -- rushing on, say the line very quickly, hoping to get this famous passage out of the way. The audience feels rather cheated then, and I used to come on -- on one production and say it slowly.

But I found that the entire audience whispered it under their breath with me, and had I stopped in the middle of the line, it would have been completed by the rest of the audience. I felt like I should have a child with a bouncing ball behind me.

So I think you've got to -- in film at least, you were -- you didn't have an enormous audience there. And in fact, in the way we shot it, which was with Hamlet looking into a mirror, it meant that in this vast state hall set full of mirrored doors, there was only myself and the camera operator. So that at least gave me a feeling of isolation. We couldn't have anybody else in the room because they would have been reflected.

You have to try and say it as truthfully and honestly as possible. One of the things about that speech that I think sometimes gets forgotten is that Hamlet has been sent for prior to this.

Sometimes, the actor's so concerned with the famousness of the speech that he comes on with that in mind, and in fact, it's quite useful as an actor to come on with some sense of "hello, where is everybody?" -- of possibly being watched. So that that quality -- the slight paranoid thing -- runs under the speech as well.

You try and say this truthfully as possible, and as if the lines had never been said before. For me, having done it a lot before, I'd got a lot of my neuroses out of the way and I also felt: do it in a mirror with Hamlet literally talking to himself and with the suspicion, which we as the film audience know to be true, that Claudius is actually watching him on the other side of what we find out is a two-way mirror -- was something that was very helpful to me.

Our atmosphere in the court was one of suspicion and spying and intrigue -- hidden doors and two-way mirrors -- and there was something that put a little sort of nervous thing under the speech, which was very helpful.

GROSS: Can I ask you to choose one of the soliloquies from Hamlet, and just talk about how you approached it in your line readings -- where to breathe; what words to accent; what words to just -- what to really, kind of, bring more to the surface; what to just kind of play down and make more subtle; how to make it sound conversational as opposed to a speech?

BRANAGH: Well, each one's different, and in each case before you approach the speech, you look at what's available to you in terms of printed editions of the text and whether you believe there's a consistency to the way the speech appears to have been punctuated.

Often, that's not the case. Some editions will give you a comma at the end of the line, instead of a full stop; or give you a full stop in the middle of the line. There'll be a different reading.

Some people are very scrupulous about Shakespeare's punctuation, and some people like to be very cavalier with it. Derek Jacoby and I often disagree about this. Derek's a great -- feels that because nobody was there to check that you can throw it all away.

And one of the things that he loves to do is to make sure that each line is said differently, particularly -- I mean, for instance, specific example. When Hamlet sees Ophelia at the end of the "to be or not to be" soliloquy, he says: "Nymph, in thy orisons be all my sins remembered" -- "orisons" being prayers or prayer books.

Now, you can say the line straight: "Nymphet, in thy orisons in your prayers be all my sins remembered." Or you can say: "Nymph, in thy orisons? Your -- at your prayers are all my sins remembered?" Those kind of decisions you make, line by line, on a soliloquy.

And you often look for words that repeat themselves. I sometimes do an exercise of looking down the end-line -- the end word of each speech, each line, and seeing whether there is a recurring pattern there.

Also, you have to work out whether there's a single idea or a single metaphor sustained all the way through the speech, so that, you know, there are endless metaphors sometimes occupying 10, 15 lines to do with whatever -- weather; the sea; mountains; intricate metaphors about insects and images to do with how that affects politics and things.

And so you kind of work it like that. And then, one of the things I tried to do with this, in each case, was to do all of that kind of work and especially if it's rhyming -- you have to be aware of that, and yet touch it lightly.

It's very important to be aware of literally the sound of it. Sometimes when you are stuck interpretively, you need to go through it and just sort of, as it were, taste the consonants. There are a lot of middle consonants and end consonants.

But as soon as you hit a little more sharply, to give definition to it, provides a kind of music that gives you an intuitive sense of what the meaning is.

So I think you throw all of that at it, and then soliloquy to soliloquy you try and say it as truthfully as possible in that moment, forgetting it -- forgetting all of that technical preparatory work, so that the final obligation to the audience is to be as real as possible in that moment; with all technical preparation forgotten about -- utterly in service to the idea of being truthful.

GROSS: What do you do -- like, the line that you mentioned before -- that Hamlet says to Ophelia about "in my orisons." Is that the word, "orisons?"

BRANAGH: "In the orisons" -- yeah.

GROSS: I mean, I wouldn't have know that means "prayer."

BRANAGH: Hmm.

GROSS: So, don't you feel like cuing the audience, like: "OK ladies and gentlemen, that word"...

BRANAGH: Well.

GROSS: "... means prayer." Or just having something -- there's so many words in Shakespeare that a contemporary audience -- an audience who wasn't filled with scholars -- wouldn't know. So how do you deal with those words so that there's some hint of what they mean, without...

BRANAGH: Well, in that instance, I think it...

GROSS: ... defining them.

BRANAGH: ... in that instance, you can be relatively simple in having her have a prayer book that she's looking at...

GROSS: Right.

BRANAGH: ... and have Hamlet in the way "in thy orisons" -- either with some sort of gesture towards it, so that the audience will pick up or intuit, if you like, a great deal of what is going on, even though they may not necessarily get the meaning of every line.

Like, there's a line in the full version -- the closet scenes -- you know, that scene where he says: "for in the fatness of these percy times" -- we used to have a lot of fun, actually, during -- talking -- because that suddenly appeared to us like a newspaper -- the Percy Times -- was a newspaper that ran through Elsinore -- but "in the fatness of these percy times" -- "percy" if I recall right, you know, meaning sort of overgrown, you know, ranc -- rancorous times, these corrupt times.

Well, you know, in the context of that scene, you just color the line with your own sense of what "in the fatness of these percy times." You know, the audience is going to get some sense that Hamlet's using the word "percy" with some ironic coloring, and in the context of other lines, they will understand.

I think it gives, if nothing else, it literally gives poetry. It gives music. It gives sounds -- the sound of the word sometimes having an impact on the ear and on the senses generally -- that wins an audience over and that is a sort of treat in itself, 'cause some of the sounds are very odd and very delicious.

And even though we may not literally understand it, I think that's fair enough. There's a great deal in the play that, I think, because it's a classic and has withstood 400 years of people throwing themselves at it, that resists definitiveness. There is mystery in there, and that mystery -- Hamlet says to Guildenstern "you would pluck out the heart of my mystery." No will pluck out the heart of Hamlet, the play's mystery.

But on the way, you can -- you can, if you serve, as we do in this one, the whole text up, I think that intuitively, the audience respond to it in a very mysterious way. And I think that that's a magical, magical thing which we underestimate because we so want to nail everything. What kind of Hamlet is it? What's his motivation? What does it mean? Can I have it in three sentences please.

It's not possible, and that's very exciting.

GROSS: Kenneth Branagh, recorded last January. His film adaptation of Hamlet has just come out on home video. We'll hear more from Branagh in the second half of our show.

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross, back with more of our interview with Kenneth Branagh recorded in January after the release of his film adaptation of Hamlet. Branagh's Hamlet has just come out on home video.

Now, your previous film was called "A Midwinter's Tale" and it was about a kind of rag-tag group of actors who were totally broke; they're all utterly eccentric; and they're doing a production of Hamlet in this closed-down church in a rural area. This is a comedy.

I want to just play a bit of a very funny audition scene in which the director of the play is auditioning a very pretentious actor who wants to star in the role of Hamlet. Here it is.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "A MIDWINTER'S TALE")

FIRST UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: Hamlet isn't just Hamlet. Oh, no, no. Oh, no. No, Hamlet is me. Hamlet is Bosnia. Hamlet is this desk. Hamlet is the air. Hamlet is my grandmother. Hamlet is everything you've ever thought about -- sex; about geology.

SECOND UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: Geology.

FIRST ACTOR: In a very loose sense, of course.

SECOND ACTOR: Can you fence?

FIRST ACTOR: I adore to fence. I live to fence. In a sense, I fence to live.

GROSS: Kenneth Branagh, was that ever you? Were you ever -- doing it that much, about the meaning of Hamlet?

BRANAGH: I've been on either end of that kind of conversation, where people are -- sort of intellectualize their response to the play or -- I remember there was one occasion where I worked with a director who was talking to the court, who was standing around while in a production of Hamlet.

Claudius and Gertrude were walking in, and he said: "and what I'd like you to do, in a strange way, what I'd like you to do is to absent yourself from yourself and give yourself to nationhood." So -- a lot of heads turned around, and suddenly somebody piped up and said: "so you'd like us to bow." "Yes, bow. That's good." "Good."

LAUGHTER

GROSS: I love this actor in it because he's so much trying to prove that he owns Hamlet, and I think everybody wants to -- it's such a kind of universal play. It's been done so many times over so many centuries, and everybody wants to prove, like, it's mine. I understand it better than you do.

BRANAGH: Yeah. And there are lots of things in it -- that you can pick up on words, characters. People can seize on things -- this particular actor, and it goes on to talk about his extraordinary research for the role of Hamlet. He said: "well, you know, normally I would have spent about nine months in Denmark to get this right -- get the feel of it; get the smell of it."

And they say: "well, what did you do this time?" He said: "Well, I got this book on the Eiffel Tower, because Laertes visits Paris, and you know, I just wanted an image in my head." Actors get very funny about this kind of stuff.

GROSS: So what was it like for you the first time you did Hamlet? How old were you?

BRANAGH: I was 20 years old and I was at drama school. I was at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, and -- in London -- and it was a panic-making experience 'cause it was very alarming to see these great sort of set-pieces be so close to each other. Now, that was a very cut version -- about two, two hours 20 minutes. But a lot of the sort of big famous bits still in.

And partly because of the cuts, but mostly 'cause this is the way it goes, they are very close to each other. You suddenly do the "rogue and peasant slave" soliloquy, which is an extraordinary piece of writing in which the actor, I suppose, is required to strike 12.

You've got to give it all you've got, 'cause there he is trying to work himself up into a state where he can revenge his father. He's trying to be like the actor you've just seen.

You finish that. You come off, and you come on immediately to "to be or not to be" -- a meditative, reflective speech which, in a sense, could be taken out of the play. It doesn't advance the plot at all. Again, naked, but in a very different way, 'cause you can't do all that ranting and raving. And it's the most famous speech ever written, probably.

And I found that all these things coming so close together meant that for me, the experience of the part, to begin with, was a sort of obstacle course.

I used to come off in the wings and ask to know where I was going to go back on again, because just getting through it, remembering it, and as Noel Coward would say "not bumping into the furniture" was quite a lot to take on board the first time.

GROSS: I imagine remembering it is pretty darn hard.

BRANAGH: Mm. It is, and of course, you don't always remember it in the right order. One of the other things Midwinter's Tale talked about were some of the famous, you know, paraphrases.

When Gertrude first talks to Hamlet in the court scene, she says: "Hamlet, cast off thy nighted color." And I was in a production with someone that Gertrude said: "Hamlet, cast off thy colored nighty."

Then there are a whole series of characters in the play -- secret characters. There's a dog in the closet scene, or at least so actors would have you believe, because the ghost says to Hamlet: "but look, amazement on my mother sits," so this little dog called "Amazement," we believed, populates the play.

Then there are classic characters -- the Hamlet charwoman, Elsie Nore. Then there's...

GROSS: That's the name of the castle.

BRANAGH: Exactly. Somebody says: "they came with martial stork, across the plains." So "Marshall Stork" is another general who's in there. And also Horatio's girl friend, Felicity.

At the end, Hamlet says to Horatio before, as Horatio's attempting to commit suicide, he says: "Absent thee from Felicity Awhile." Her second name is "Awhile." "Felicity Awhile" -- Horatio's girl friend. The hidden meaning in Hamlet.

GROSS: Well, the first time you did Hamlet, were there any hidden meanings that you saw that you thought: "well, I am going to bring this to the surface and I will show what Hamlet is really about."

BRANAGH: Well, one of the things I did that I lost over various productions of playing it, was a sense that he absolutely goes mad, live, in front of the audience, in the scene with Ophelia -- in the nunnery scene. He meets this woman who has been banned from seeing him. The pair of them, it seems, love each other very much, but he feels that she's been unjust. She feels he's behaved irrationally.

Anyway, in the midst of this confused, almost adolescent, you know -- "will you be my boy friend?" "no." "will you be my girl friend?" "no" -- sane. He suddenly says: "where is your father?" And she says: "at home, my lord," which is a lie because she knows that her father is watching.

And I chose that moment in that very first production to do a great kind of spastic convulsion of heartbreak and madness, with eyes rolling and all sorts of nonsense that then left me pretty much nowhere to go for the rest of the play because I was mad in the middle of the third act, so I had two acts of being completely potty.

So I dropped that after a while. I still think it's quite a heartbreak. I just don't think that he goes as erratically mad as I did back in whenever it was -- 1980.

GROSS: What did you director tell you?

BRANAGH: Oh, director was a very cool guy. He said: "yeah, just go with it, man, you know. Just kind of see where it takes you, you know. It's quite interesting -- interesting choice."

GROSS: Kenneth Branagh, a pleasure to have you here. Thank you so much.

BRANAGH: Thank you. My pleasure.

GROSS: Kenneth Branagh, recorded last January. His film adaptation of Hamlet has just come out on home video.

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest: Kenneth Branagh

High: Actor and director Kenneth Branagh. His most recent film "Hamlet" has just been released on video. There's a companion book to the film which includes the screenplay, introduction, and film diary. Branagh's other films include adaptations of Shakespeare's "Henry the Fifth", with himself in the title role, Othello, playing Iago, "Dead Again," a psychological thriller starring Branagh and Emma Thompson, and "Much Ado About Nothing," also starring himself. Branagh was born in Northern Ireland, studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, spent two years with the Royal Shakespeare Company, as well as acting, managing, and directing other groups and working on several BBC productions.

Spec: Media; Movie Industry; Authors; Shakespeare; Europe; England; Hamlet; Kenneth Branagh

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright (c) 1997 National Public Radio, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by Federal Document Clearing House, Inc. under license from National Public Radio, Inc. Formatting copyright (c) 1997 Federal Document Clearing House, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to National Public Radio, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission. For further information please contact NPR's Business Affairs at (202) 414-2954

End-Story: Kenneth Branagh

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: JULY 25, 1997

Time: 12:00

Tran: 072502NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Keith Haring

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:40

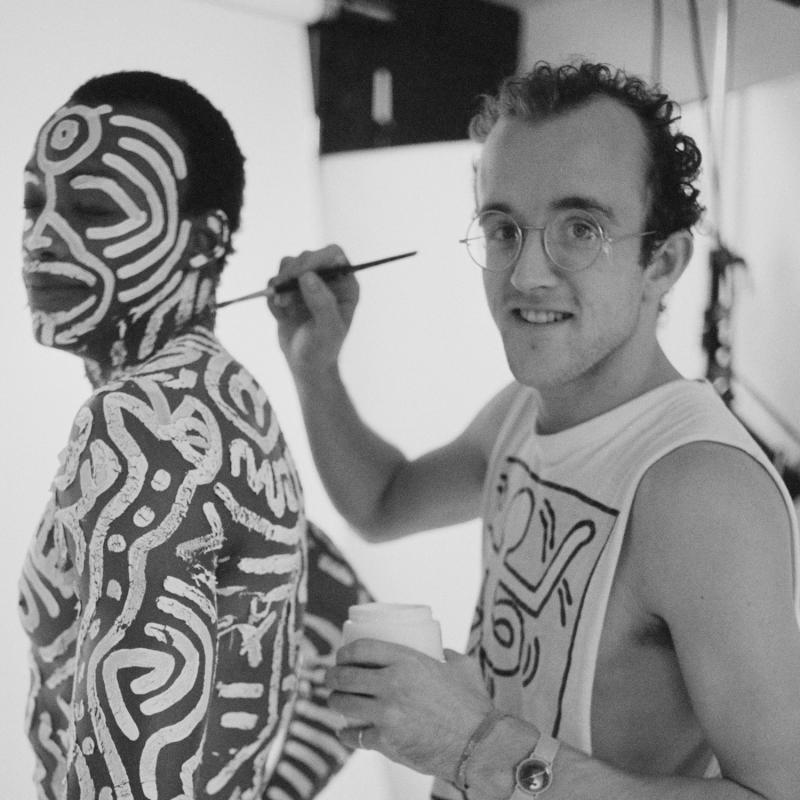

TERRY GROSS, HOST: The Whitney Museum in New York is showing a retrospective of Keith Haring's work. He became international renowned for work that used to get him arrested. Haring's early work took its cue from New York City subway graffiti. He made the rounds of subway stations doing quick chalk sketches on train station walls.

The designs were cartoon-like human figures, barking dogs, hearts, and crawling babies. Rush hour provided a bigger audience for his work than any gallery or museum could. Haring became an important part of the East Village art scene, and eventually became an art superstar.

But he continued to insist that his work have a life outside the art world. He painted colorful murals on walls and buildings; created public sculpture; and decorated rock clubs. He also opened a pop shop, where he sold items like T-shirts, radios, and refrigerator magnets imprinted with his colorful cartoon-like designs.

Haring died of AIDS in 1990. On this archive edition, we have an interview we recorded in 1987. He told me what it was about graffiti that excited him when he moved to New York City from Pittsburgh in 1978.

KEITH HARING, VISUAL ARTIST: Immediately after coming to New York, although I was going to galleries and seeing other things also, one of the things that struck me most was the work in the subway, because trains were really -- almost every train was painted, and they were really beautiful.

GROSS: Like murals on the sides of whole train cars.

HARING: Yeah, the entire cars, usually -- sometimes inside and out. And very -- it was in a way very pop. I mean, the characters -- using colors and cartoon characters which had come out of, I think, the whole generation of people that were growing up with really good cartoons on television and really good sort of pop culture.

GROSS: So you wanted to do something that was your version of that kind of expression?

HARING: Well, I think -- yeah, I mean for the first two years, I didn't do anything on the street. I mean, I was sort of watching and appreciating it, but not -- I -- the thing that I wanted to not do was to sort of jump on the bandwagon and copy their style or do something that looked as if it was just an imitation, or something, of what I was seeing on the trains.

So the first time that I did something on the street was really only when I had just discovered something that I thought made sense to be on the street. Because my -- although I had a lot of things in common with these graffiti things because my real -- whole background had really been in cartooning.

And so, my concept and sense of the line and of the scale that I was seeing there and of the sense of color et cetera was very much in tune with them. But there was also something that was distinctly different in the kind of drawings that I was starting to do.

And it was really only when I started drawing these sort of images, which in the beginning were just human images and animals and spaceships and pyramids and things in different combinations and juxtapositions -- it was only then that I really had something to put on the subway.

Because before that, I had been doing only abstract drawings -- sort of -- you know, doing, I guess, pseudo-abstract expressionist or sort of gestural abstract drawings, which didn't make sense to me to be on the street. But as soon as I had this vocabulary, kind of, of images, it almost necessitated that it should be on the street.

GROSS: One of the things you were doing was drawing in subway stations.

HARING: Yeah, that's -- well, that started, again, started after I had come up with these characters and then by accident, sort of, discovered that there were all these empty panels in the subway, inside the station, when they -- where they usually have advertisements. When they don't have enough ads, they cover the space with empty black paper to cancel out the old ad.

And although they had probably been there for years, one day I sort of -- I felt like I had discovered it 'cause I had never seen anyone draw on it before. And it immediately seemed like the perfect place to draw.

First of all, because I could draw very quickly because these things I was drawing were very simple and very, very quick -- sort of, you know, line drawings. And also because it was a very borderline case between being legal and illegal.

You know, because it wasn't right on the wall and because I was drawing with chalk, it was sort of a delicate sort of situation when I would get caught, because it was hard to really say that you were defacing, because you were drawing with chalk, and also you were drawing on a paper panel that would inevitably be changed and replaced within a week or two weeks.

GROSS: You were fined several times by the police and I think arrested once?

HARING: Well, I...

GROSS: More than that?

HARING: ... was arrested several times and fined several times. But in those cases, a lot of times it was -- it would start out being a little bit scary, but it would end up being a really amusing situation because the cop who caught me usually didn't know who I was, but when he would take me to the station, a lot of times we'd find out that other policemen in the station were eager to find out who this person was.

Because after a year or two, everyone that rode the subways knew the drawings, you know, 'cause if you rode the subway, you know, even just once a week, you'd see, you know, several drawings. And this went on for a five-year period.

So I had a large following of people in the subway, many of which were policemen that spent their time in the subway that were very eager to find out who I was.

I had a great -- actually, one of my favorite stories was coming out of a restaurant with Andy Warhol when we were eating, and a cop came up to him and wanted his autograph. And Andy was always -- the first thing Andy would always do was introduce the other people.

He was always sort of playing down his own importance and saying: "no, well, you have to -- here, you should get his autograph because a famous graffiti artist." And the cop said: "really?" And he started -- the cop was in uniform and he started taking out his ticket book.

And so I sort of looked at Andy like: "what he?" -- you know -- "he can't give me a ticket now for something I did before." And he opened the ticket book and on the inside of the ticket book was a sticker with my "radium baby" thing on it.

So it was sort of, you know, it sort of turns up in funny places, you know. So I actually had a lot of cops that were fans at the same time.

GROSS: One of the projects you have taken on is a store in which you sell T-shirts and buttons and other items with you...

HARING: Toys, coloring books, posters et cetera.

GROSS: ... with your designs on them.

HARING: Yeah.

GROSS: And even the walls of the store are painted...

HARING: Right.

GROSS: ... by you, in your designs. And this has been very controversial in the art world. Some people think it's really exciting to get your work out on common objects, like T-shirts. And other people think it's a sign that you've really sold out and made your art into the equivalent of designer jeans.

HARING: Right. Um, yes. For me, it was not something that was a matter of choice. If I was being honest to myself and, more importantly, honest to the work itself -- to the drawings and to, even down to the way the line itself -- the kind of line -- the kind of image that I was creating -- then the pop shop grew out of something that for me was inevitable.

The same way that when the drawings of these images, which were about communicating information and ideas, existed and then because they existed, they, almost by the nature of themselves, they demanded to be in public which made them be in the subway.

In the same way, once they were in the subway and had effectively started to communicate and become part of the consciousness of not only New York City, but then through magazines and video and television, to the world -- it also necessitated that I continue with that idea and pursue it in a way that was honest to myself and to that thing, in that definitely -- I could have and very easily, I guess, hidden within the safety of the art world and stayed in my studio and produced paintings which sell on the art market for very inflated prices because that's what the art market is about. That's a whole 'nother question.

But the -- for me, it was inside the work itself that it was not owned by me. It was bigger than me and it was saying that that should be part of the whole world. And the only way to really make that happen was to do things, first of all, things through commercial publication, meaning something like album covers or advertising in magazines.

And then -- but also to make things on things which people could have -- so that people could have a piece of this whole thing.

GROSS: So you don't see it as commercializing your art. You see it as making your art accessible to people who don't have the money to buy a canvas.

HARING: Well, I mean I can't -- of course, cannot deny that it is not commercializing it, because that -- I mean, that's the way the world works. I mean, you can't -- it's impossible to give away things to everyone. Right?

I mean, I spent -- have spent a lot of time doing giveaway things also. I mean, printing posters and giving them away for free at rallies -- anti-nuclear things or Free South Africa et cetera. Or giving away badges and little things like that.

But on a -- to really start -- to really get it and make some real impact into other people's minds and the world et cetera and culture, the only way to really have any effect on that was to work within that system.

I mean, you can't really be outside of a system and criticize it or comment on it and change it or have any impact without being inside of it and sort of working through the same mechanics of that system.

GROSS: You were good friends with the late Andy Warhol, and he was really the master of mass-produced art. Did you get any advice from him on the kind of undertaking that you've done with the pop shop? Advice on merchandising your art or on mass-producing it?

HARING: Not necessarily specific things, but Andy was always full of encouragement. And, I mean, yeah, well actually we discussed lots of ideas, but -- and discussed almost everything, I guess -- I mean, because we'd talk about different things. But Andy was -- would generally support almost anything that you said, so it was sort of hard to necessarily -- to get really a critical answer out of him.

But more than by conversation, I learned a lot of things from Andy just by watching and by example. I mean, Andy was one of the best sort of teachers of people just by what he -- saying one sentence or just by example, he was a kind of incredible philosopher that a lot of people looked up to and learned things from.

At the same time, watching the way that the art world -- the "established art world and art market" treated Andy, I also learned a lot of things about the risks and the dangers of doing that. But for me, anything worth doing is worth taking a risk.

I mean, if you look -- for instance, if you look at a painting of Andy Warhol's now, even after his death, aside of a painting by Jasper Johns or something like that, the prices are -- they have nothing to do with each other.

And -- but I -- for me, the value of something cannot be determined by something like the art market or the art world. And the value -- for me, the value of Warhol is 10-fold greater than Jasper Johns ever will be. The amount of people and the amount of effect that he has had on the culture and the world and thinking is incredible.

GROSS: I guess one of the things that probably surprised a lot of people was the vodka ad that you did the illustration for.

HARING: Well, actually, that's -- I mean, it's funny because that's the only commercial thing that I've done in the United States. The vodka ad I actually got into because of Andy. Andy had done the ad for Absolut vodka last year, and Andy actually suggested the idea to me and asked me if I wanted to do it.

GROSS: This is Andy Warhol.

HARING: And for me, the fact that Andy had done it first had totally OK'd it for me. Although there are things that Andy also did that I wouldn't do after him, but the people that were doing the vodka ad were very -- they -- you know, they were sort of genuine about it and were very clean.

One interesting thing, which actually I -- just happened to me last week, found out that -- I was talking to a friend that's in jail on Ryker's Island, and was telling me that -- that he had my Absolut vodka ad up on his wall in the cell, right?

And all of a sudden it dawned on me that I've -- that I -- anything anyone negative could say about me was totally washed away just by that, because the fact that that was maybe the only way that my art could have gotten into -- inside of a prison or places where people are really -- have no other access to any kind of thing, but that he could have taken it out and put it on his wall, and it was still -- it was still art.

I mean, it was -- and so -- you know, it was totally effective even if it only got to that one person.

GROSS: Keith Haring, recorded in 1987, three years before he died of AIDS.

The Keith Haring retrospective will be at the Whitney Museum in New York through September 21.

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest: Keith Haring

High: The visual artist Keith Haring emerged when punk and New Wave music and the hip-hop scene of graffiti artists and break dancers were the background and source for music and art appearing throughout New York. His work responded to, and helped form and translate, the city's street culture. He died in 1990 at the age of 31. The Whitney Museum in New York is currently showing an exhibit featuring many his works through September 21.

Spec: Art; History; Cities; New York; Keith Haring

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright (c) 1997 National Public Radio, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by Federal Document Clearing House, Inc. under license from National Public Radio, Inc. Formatting copyright (c) 1997 Federal Document Clearing House, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to National Public Radio, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission. For further information please contact NPR's Business Affairs at (202) 414-2954

End-Story: Keith Haring

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: JULY 25, 1997

Time: 12:00

Tran: 072503NP.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Air Force One

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:55

TERRY GROSS, HOST: Michael Douglas has done it. So has Gene Hackman, Jack Nicholson, James Garner, and Jack Lemmon. They're all leading men who've played the president.

Now it's Harrison Ford's turn. Ford stars in "Air Force One," the new summer action thriller that opened today.

John Powers has a review.

JOHN POWERS, FRESH AIR COMMENTATOR: It's hard to know what to make of the president these days. Earlier this year, in "Absolute Power," he was a sexually sadistic philanderer who'd murder to keep in office. Now, he's turned into Indiana Jones.

The movie is Air Force One, and Harrison Ford stars as President James Marshall, a war hero and family man whose grown ashamed of himself for bowing to political expediency in dealing with terrorism. At a speech in Moscow, he vows that he'll never do this again -- he'll never negotiate with terrorists.

But as he flies home to the states with his wife and daughter, Air Force One is hijacked by a fanatical group of pro-Russian soldiers led by Gary Oldman, who demand the release of a messianic general who's in prison.

Marshall has to decide whether to negotiate or take back the plane himself. Bet you can guess which one he chooses. After all, this is no wimp, but a take-charge guy whose authority is obvious when, calling from Air Force One, he finally reaches vice president Glenn Close and his cabinet at the White House.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "AIR FORCE ONE")

HARRISON FORD, ACTOR, AS PRESIDENT MARSHALL: Listen to me -- you know who I am. I'm the president of the United States.

SOUND SHRIEKS

GARY OLDMAN ACTOR, AS RUSSIAN TERRORIST: Don't think that means I don't shoot you. Put your hands behind your head and move. Go on (Unintelligible).

SOUND OF FOOTSTEPS

FORD: (Unintelligible) -- what more can my people do? Tell the F-15s to fire at the plane? Even if they tried, we're equipped tactical counter measures.

GLENN CLOSE, ACTRESS, AS VICE PRESIDENT: He's talking to us.

TERRORIST: What are you telling me? What do you mean?

FORD: I just want you to feel secure. That way, no one will get hurt. The computer will fly circles around any missile they fire at us, and they'll hit just a shock wave.

CLOSE: He's telling us what to do.

FORD: Believe me. All that'd happen is we'd get knocked off our feet. That's all.

TERRORIST: Shut up.

SOUND OF BODY FALLING TO FLOOR

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: Oh God. Is he saying what I think he's saying?

CLOSE: If we're going to act, we have to act now.

ACTOR: It's too risky.

CLOSE: The president is up there with a gun to his head.

SECOND ACTOR: He's asking us to do that? To Air Force One?

CLOSE: He's not asking. Your commander in chief has issued a direct order. Do it.

POWERS: It's a defining feature of pop culture that it rewards a catchy idea, be it the energizer bunny or Joan Osborne's (ph) chorus to "What If God Was One of Us"?

Air Force One is going to be a hit, not because it's a great movie, but because it has a terrific hook: the president takes back Air Force One. Can't you just hear someone pitching that?

There's something wonderfully silly and compelling about the idea of making the president the hero of what's essentially a Steven Segal picture. After all, who can resist watching a 50-something commander in chief wipe out a bunch of cruel, blustering, self-pitying Russkies with a penchant for overacting?

As he showed in "Das Boot," the German director Wolfgang Peterson knows how to build suspense using confined spaces. We always know exactly where Marshall is in the plane and where the bad guys are too. Such precision makes the ludicrous seem almost realistic, but Peterson's skill doesn't save Air Force One from wearing you out.

Like nearly all summer movies, it doesn't know when to end -- piling on climax after climax, spectacular scene after spectacular scene, in a desperate attempt to top itself and all previous action flicks.

Like all such movies, it also tries to come up with a tag line, like "make my day" that will be on everyone's lips. Marshall's big line here is "get off my plane," which actually sounds a lot like the attitude of our commercial airlines these days. I almost expected him to add "and stop whining because we didn't feed you lunch."

As you'd expect, the pundits are already pontificating about what this and all the other presidential movies reveal about our national psyche. Much of this speculation is overblown nonsense, for one should never confuse Hollywood movies with what America is really thinking.

Still, it does say something about Bill Clinton's aura of ambiguity that since he took office, we've been inundated with films that show the president to be everything from a hero to a monster. And in James Marshall, Air Force One does seem to offer the kind of president that millions say they dream of -- sort of a white Colin Powell.

He's a war hero. He says what he means and means what he says. He's tough enough to take care of business, yet tender enough to have a woman vice president. Harrison Ford even seems presidential, although in real life he's not tall enough to get elected.

GROSS: John Powers is film critic for Vogue.

Dateline: John Powers; Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest:

High: Film critic John Powers reviews "Air Force One" which stars Harrison Ford.

Spec: Movie Industry; Books; Tom Clancy; Air Force One

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright (c) 1997 National Public Radio, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by Federal Document Clearing House, Inc. under license from National Public Radio, Inc. Formatting copyright (c) 1997 Federal Document Clearing House, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to National Public Radio, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission. For further information please contact NPR's Business Affairs at (202) 414-2954

End-Story: Air Force One

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.