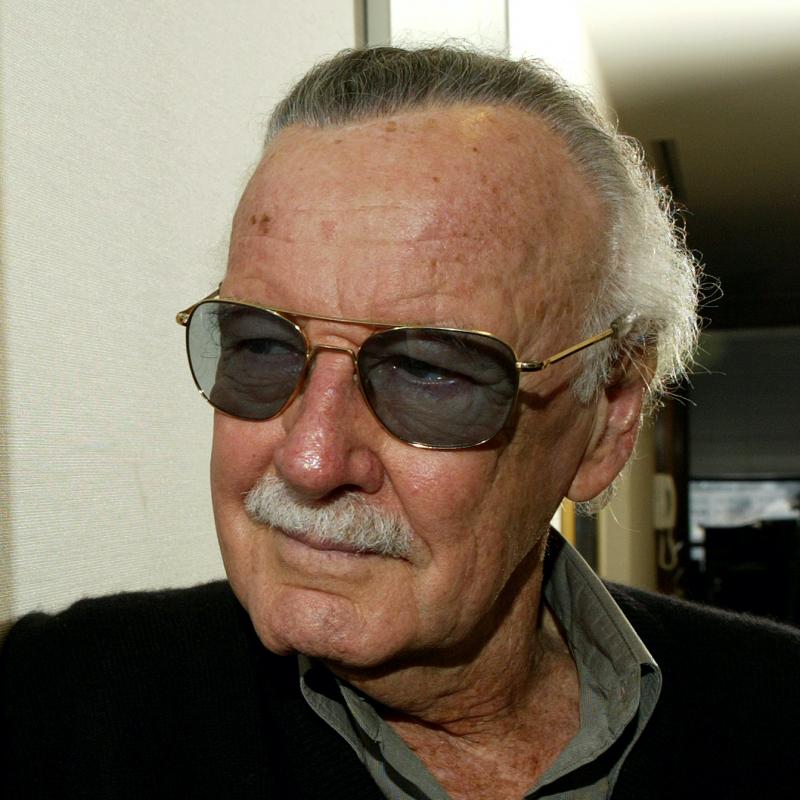

From the Archives: Stan Lee Discusses Marvel Comics.

Cartoonist Stan Lee-- the creator of such Marvel comic book superheroes as Spiderman, The Incredible Hulk, The Fantastic Four, and The X-Men. He joined Marvel comic books at the age of 16, more than 40 years ago. The movie The X-Men, based on his comics, opens this weekend. (ORIGINAL BROADCAST: 10/17/91)

Other segments from the episode on July 14, 2000

Transcript

DATE July 14, 2000 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: Anthony Minghella, director and screenwriter of

"The Talented Mr. Ripley," talks about his life as a child and

the making of the film

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

"The Talented Mr. Ripley" has come out on video. On this archive edition, we

have an interview with the writer and director of the film, Anthony Minghella.

Minghella also directed the film adaptation of "The English Patient."

"The Talented Mr. Ripley" is adapted from a novel by Patricia Highsmith. As

the story begins a wealthy industrialist wants to convince his son, Dickie, to

return home from the Bohemian life he's living in Italy. The father

mistakenly believes that a young man named Tom Ripley is Dickie's old chum

from Princeton. When the father offers to fund Ripley to go to Italy and talk

Dickie into coming home, Ripley plays along with the father's mistake and

pretends to be Dickie's old friend, because Ripley's broke and he wants the

free trip. Once Tom Ripley arrives in Italy and gets a taste of Dickie's

life, his money, and his freedom, Ripley wants it for himself. Rather than

bringing Dickie home, Ripley stays in Italy, attaches himself to Dickie and

finally appropriates Dickie's identity. In this scene, one of Dickie's

friends, played by Philip Seymour Hoffman, is looking for Dickie, who has

disappeared. The friend pays a visit to Tom Ripley, who's living in a fancy

apartment he says he's sharing with Dickie.

(Soundbite from "The Talented Mr. Ripley")

Mr. MATT DAMON (Tom Ripley): Did this place come furnished?

Mr. PHILIP SEYMOUR HOFFMAN (Freddie Miles): It doesn't look like Dickie,

it's horrible, isn't it? So bourgeois. You know, in fact, the only thing

that looks like Dickie is you.

Mr. DAMON: Hardly.

Mr. HOFFMAN: Hm. Wait a second, have you done something to your hair?

Mr. DAMON: Is there something you'd like to say, Freddie?

Mr. HOFFMAN: What?

Mr. DAMON: Do you have something you'd like to say?

Mr. HOFFMAN: I think I'm saying it. Something's going on.

GROSS: "The Talented Mr. Ripley" is the story of someone who crosses the line

in trying to recreate himself and live the kind of charmed life he envies.

Mr. ANTHONY MINGHELLA (Director, Screenwriter): The film asks the question--I

think, a central point--it asked whether to be a fake somebody than a real

nobody. And I think at the heart of the film is a kind of debate about the

cost of giving up on yourself, the cost of, in some ways, buying into what

are, I think, even more pressing messages than they were 50 years ago about

personality, about the values of who you are. I think we live in an age where

there's so much of a barrage of messages from the media about changing

ourselves, about, in some way, feeling that we are intrinsically inadequate as

human beings and that what we have are actual talents, are things we should

trade in in favor of better hair, or better bodies, or better lives, or

better wives, or better couches or better something. And so I think what

attracted me to this story was the opportunity to look at the moral phrasing

of this and also the fact that as a narrative, it talks about somebody who,

perhaps, appears to get away with what he's doing. And I think the film tries

to examine the difference between public accountability and private justice.

GROSS: What is it that Tom Ripley most envies and wants that Dickie, the

wealthy young man in Italy, seems to have?

Mr. MINGHELLA: Well, I feel that if you were trying to compare the two

characters, one of them is a man who walks into a room and says, `Hello, I'm

Dickie Greenleaf, love me,' and people do. And Ripley walks into a room and

says, `I'm Tom Ripley. Might you love me? I know you won't.' And so I

think in some ways, what he aspires to is the sense of being selected that

seems at the heart of Dickie's personalties, expectation of being embraced,

whereas I think that Ripley has an expectation of being rejected. I think he

feels that he has to lock away who he intrinsically is, because if people

actually saw him, they would reject him. I think that's something which I

certainly can relate to, and I think is part of the human condition in some

way. I think that one of the, I suppose, phenomena of traveling from child

into adulthood is an essential recognition that we're alone and an essential

desire not to be alone.

GROSS: You know, as you said, Tom Ripley, the character says it's better to

be a fake somebody than a real nobody. Frank Rich, writing in The New York

Times Magazine section, said `In this age of rampant reinvention when

political candidates, entrepreneurs and criminals change selves like

quicksilver, "The Talented Mr. Ripley" may be Hollywood's most chilling and

up-to-date portrait of our national character.' What do you personally relate

to about the character of Tom Ripley? 'Cause there must be some personal

connection there.

Mr. MINGHELLA: Oh, I think I felt a huge connection to Ripley when I read

the--or re-read the novel and I came to adapt it. I think that essentially,

it's this feeling of being on the outside of things, of being strange in some

way; of feeling, too, that you have to be secret about what makes you

particular. I suppose it goes back to the sense of being in a school yard

when teams are being selected and that fear not being chosen, the fear of not

being admitted, really, to a life that you aspire to. And particularly in

Britain, where I was brought up, where I think the issues of class are

tattooed on your forehead. You walk around with second rate and second class,

you know, imprinted on your forehead. And I think that I'm very, very alert

to the striations of class and to the sense that there's a better life being

lived, that your nose is pressed up against the window of a life. And, you

know, my family is Italian and I was growing up on a small island off the

coast of Britain, and so I felt there was so many membranes between me and

what seemed to be the center of things. And, you know, I don't want to make

any special claim for that, because I think all of us have within us some

reference to what it feels like to be on the outside. And those were my

particular things. I mean, I was perfectly happy growing up. It's just that

I always felt, in some way, that I didn't entirely belong. And I think that

feeling of not belonging is particularly exacerbated in, you know, late

adolescence, early adulthood, which is really where this story is situated.

It's very much a story of young people trying to reinvent themselves in the

country of Italy, in Europe, which I think had a particular attraction to

Americans over the course of this century.

GROSS: But what's different here is that, you know, the main character takes

these feelings, that many of us experience, of loneliness and alienation and

jealousy--he takes it to extremes; he crosses the line and becomes kind of

pathological. Why do you think it's interesting to build a story around a

character who we can all identify with, but have him go much further in

horrible ways than we would hopefully go?

Mr. MINGHELLA: Well, because I think it's a parable in some ways. I mean, I

couldn't help thinking in that moment where Ripley says, `I'm Dickie

Greenleaf,' that it was rather like a Grimm's fairy tale, like a contemporary

Grimm's fairy tale. Be careful of what you wish for. I feel the gods laugh

at him when he says, `My name's Dickie Greenleaf,' and they say `Well, if

that's what you want, you can have it.' And it sort of tries to examine the

toll involved in giving up on yourself. And so, in some ways, it's a

nightmarish version of feelings that we've all had. And I think that's what

fiction is for, in some way, to reflect some of the journeys we might make.

I mean, where I understood this film, in some way, was, you know, partly

connected with something that happened to me many years ago, which was I had

written a play, and it was about to be produced in the West End, in London,

and the director, Michael Blakemore, had invited me out to share his house off

the coast of France while we talked about the film--the play. And we went

swimming, and it was a wonderful day, and we were swimming on our backs and

speculating about the production of this play and what might happen and what I

might rewrite. And then at one point he said, `Oh my goodness, I think we've

drifted out from the shore.' And I looked back and we were about a mile and a

half from land. And I thought, `Well, gosh, I'm going to drown.' And I

starting flailing out and panicking and thinking I'd never get back.

And in some ways, that seems to me to absolutely corral the emotion and

sensation that Ripley experiences in this film, which is that from a series of

rather small missteps that he makes, small lies, they accumulate into, you

know, a tangled web. And, in a way, it's, I suppose, exacerbating and

polarizing the journeys that we all make. We all are guilty of sins of

omission and commission about ourselves and our aspirations. And fiction, in

some ways, can give you back an exaggerated version of the consequence of

those ambitions and desires.

GROSS: Now Matt Damon plays Tom Ripley, the character who desperately wants

to be this young, wealthy man who he's become acquainted with. And I think

it's really an excellent performance. In a way, the role is about acting,

because Tom Ripley takes on the character of somebody else. And Matt Damon's

face is really interesting to watch in this. You see him as he tries to cover

up emotions; you see certain emotions kind of wiping across his face and then

disappearing. His face just registers all kinds of interesting, fleeting

things. And I'm wondering if you auditioned him for this at all or just

assumed, based on other performances, that he could do what was needed for the

role.

Mr. MINGHELLA: Well, I think the casting process is rather like dating blind.

You know, you meet somebody and you try and extrapolate from the few hours

with them whether you could go on a relationship with them, on an adventure

with them. And obviously you have some prior information with an actor

because you've seen the work that they've done. Although, at the time that I

cast Matt, none of the films which had made him Matt Damon had actually

appeared. I was lucky enough to see an early cut of "Good Will Hunting," and

then I got to meet and to talk to him. And what struck me about him, really,

was his own passionate conviction that he was well cast in this part and his

really transparent understanding of the screenplay. And I felt a great fellow

feeling with him and it was vital in this film that I did have an accomplice

on the other side of the camera because Ripley's in every single scene of the

film. I'd never really written a character who so dominates the proceedings.

But the thing that you mention is very true about the fact that a great deal

of Ripley's performance--of Matt's performance as Ripley--is about watching

and observing and reacting. He doesn't have a great number of lines in the

film. He's very much a presence rather than a voice. And I think it needs an

extraordinary performance to let you into him. And I tried in a way, to make

the camera an enquiring camera in this film, Enquiring into Ripley's mind, but

also, in some ways, trying to look at the world through his eyes. The film is

full of distorted self-images, it's full of a very particular way of seeing.

And I kept imagining that the camera was simply reflecting what it was that

Ripley saw in the world.

And I think that, as a performance, it's an absolutely extraordinary one

because it has none of the frills, and bells and whistles and pyrotechnics,

which, you know, normally dignify a great piece of acting. This is all about

staying still and allowing the events of the film to wash over you and let

people somehow into the secrets that are going on in your head. And I think

he has that amazing transparency. He reminded me a great deal of Juliet

Binoche in a way, who I think is another actor who you feel privilege when

you look at, because you feel that she's inviting you into the soul in some

way. And I think that Matt has pulled off exactly the same really remarkable

feat in this film, which is he's--first of all, he's transformed himself from

who he actually is. I mean, he's a very centered and blessed person, very

intelligent, very articulate, stands very steady on his feet and has that sort

of heavy-footed, contemporary gait to him. And he's invented this extremely

delicate, skinless, febrile character. And that in itself is extraordinary,

and is sustained throughout the film. But also, as you said, there's

something that you feel, that you have access to the inner being of this

character without using any of the tricks that you might need to suggest that.

And he also, within the film, recreates himself as somebody else. So there's

a whole series of acting exercises going on, and it's real dignifying, I

think, of the screenplay.

GROSS: My guest is screenwriter and director, Anthony Minghella. More after

a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is Anthony Minghella, director of "The Talented Mr. Ripley,"

and "The English Patient."

Now you said that part of the reason why you kind of have this sense of

empathy for Tom Ripley is that you felt like a bit of an outsider growing up

in an Italian family that had emigrated to Britain, and lived in the Isle of

Wight. Now which part of your family came first there? Was it your

grandparents, your parents?

Mr. MINGHELLA: Well, it's a very convoluted story, but essentially, my mother

had fetched up in the Isle of Wight just after the war, basically on the

advice of a priest. Her family had settled from a small village in Italy near

Monte Cassino and her father had disappeared off to Ireland, I think, to lead

a completely new life and had abandoned my grandmother and her three

daughters. And so, with the wisdom and the navigation of the local parish

priests in Scotland, where they, for some reason, were living, they were

redirected down to the Isle of Wight, a place they had never heard of. And

probably, they just wanted to get rid of them. And so--it was as far south as

you can go in the British Isle.

So they went down to the island, and my father, meanwhile, was living in a

village very close to Valvuru(ph), where my mother came from, and was brought

over as many young men were, were brought either to America or to Britain,

where the wealthy families, you know, would pay their train ticket or airfare

and--in a way to provide cheap labor. And he was taken in by an ice cream

making firm in Portsmouth, which is a few miles from the island. And the

people there said, `Well, you know, there's a girl who had come from a village

next door to you in Italy across the way.' And so they ended up courting each

other on the Isle of Wight ferry. There's a long pier and ride, and then they

would troll up and down the pier in the morning and then my father would go

back to the work, and eventually he married and they settled on the island,

and I was born a couple of years later.

GROSS: Well, as a storyteller, it must've been interesting to grow up with

such an interesting story about your own family. Were there a lot of stories

in your family about the grandfather who took on a new life and disappeared,

abandoning the wife and kids?

Mr. MINGHELLA: Oh, absolutely. I mean, that was the whole stuff of my

childhood. My grandmother, with whom I was inordinately close--in fact, you

know, I don't think--it's the closest relationship I've ever had with anyone,

probably. And she and I would walk every morning along the beach on the

island and she would, I suppose, explain the world to me as far as she

understood it. She was a very naive and wonderful woman, and, I don't think,

ever fully accepted that her husband wasn't going to come back to her and,

even though that--they had been separated for 30 years, always imagined that

he was about to come home. And I think that was the first insight I had into

this whole business of the fact that probably my grandfather had a completely

new, and perhaps fulfilling, and perhaps honorable, and perhaps appropriate

life with somebody else in Ireland, while my grandmother was fantasizing about

his return and the inordinate amount of pain that they caused each other and

which stayed with them right up till after my grandfather's death.

There were some extraordinary scenes in Dublin where my grandmother and her

children went to--who are now grown women--went to retrieve the body of their

husband and father and bring him back, as it were, because their notion was

that this woman might have had him for his lifetime, but they would have him

for eternity. I mean, the sort of whole drama of that and just the impact

that it had on everybody's lives was, I'm sure, the beginning of my interest

in trying to examine, you know, just the frailty of people pursuing what they

feel they need and what they feel they want and just the yearning that people

have for each other and the amount of pain they carry around with each other.

GROSS: I want to ask you something else about your family. I know your

father ended up making ice cream?

Mr. MINGHELLA: Yes. He's a great ice cream maker. He's doing it even as we

speak now.

GROSS: OK. And I think that there was a brand called Minghella Ice Cream.

Is that right?

Mr. MINGHELLA: That's absolutely true, yeah.

GROSS: So were you--I mean, would this have been like being the son of Ben &

Jerry's or something? Or the son of Sealtest when I was young or...

Mr. MINGHELLA: I wish it would have been the son of Ben & Jerry's.

GROSS: ...son of Haagen-Dazs or...

Mr. MINGHELLA: I would never have got a job. I just would have retired by

now. I mean, it--funnily enough, I think one of the Ripley experiences I had

when I was growing up was that on the island, which is essentially a very poor

place, it's a wonderful place but 90 percent of the population lived from hand

to mouth. But it has this border of large, you know, of rich people,

extremely privileged people who descend in the summer months. It's always

been--since Queen Victoria's time, it's been a place where the wealthy and

privileged have gone to spend their summers. There's a big, you know, boating

regatta there every year at Kouws(ph), which is the home of sailing and so it

was very much the experience of my growing up.

The island would become full. I wouldn't use the word infested, the word that

came to my mind. It was full of the young and privileged and gorgeous and

wealthy every summer while we were toiling away. And my summers were always

spent behind the glass of an ice cream van serving ice cream. And I certainly

remember the feeling of not being inside the world I wanted to be in but

rather imprisoned in the cage of this ice cream van.

I remember once driving along, delivering some ice cream in my father's van

and being stopped by two young, very beautiful people who very well could have

been Dickie Greenleaf and Marge Sherwood, who wanted me to give them a ride.

And so they got into my van and after a while I asked them where they were

going and they said, `Oh, we're not going anywhere. We just wanted to sort of

feel what it was like to be picked up by a local and taken somewhere.' And I

never felt so humiliated and so clear about my own social standing. And I

remember vowing then that I would escape from the prison of the ice cream van

and try and reinvent myself. So I suppose that was my most defining Ripley

moment.

GROSS: Before I let you go, I have to ask you. Did you ever see the

"Seinfeld" episode--everybody must ask you this--in which Elaine wanted to see

"The English Patient" and didn't like it, but her boss, Peterman, loves it.

And so rather than get into a fight with him, she tells him she didn't see it.

So he, of course, has to do everything in his power to get her to go because

he's sure she's going to love it. Everyone must ask you if you've seen the

episode. Did you see it?

Mr. MINGHELLA: Well, you know, I saw a piece of it when I was in Los

Angeles. I haven't seen the whole episode. I was enormously flattered that

they took the trouble even to--it was an index to me of how much "The English

Patient" had pervaded the public consciousness, that anybody would be remotely

amused by this. And, in fact, in Britain there was a much more sort of

devastating and just devastatingly funny attack on "The English Patient." It

was called "The Toy Patient(ph)," in which they dressed up some bears and, you

know, woolen rabbits and played out the story with puppets. And it was much

funnier and much better than my film. So, I mean, I just took it as a great

compliment really that anybody cared enough.

GROSS: So what...

Mr. MINGHELLA: And I think the other thing I would say is this. You know,

that I feel so uniconoclastic as a filmmaker and it's always very strange to

me that people can either be so passionately for or against what I'm doing

because I feel like the most equivocal person in the world. And when I made

"Truly, Madly, Deeply," I remember that it--in one week I remember reading a

list of somebody's 10 favorite films of all time and getting that glow of

pride reading that somebody thought this was one of the 10 best movies ever

made. And the next day, on BBC Television, they had a wonderful program where

people could consign the things they most hated to "Room 101," this program

was called. And the very first thing on the next day that I saw was this guy

saying, `And the first thing I'd put in Room 101 is "Truly Madly Deeply."' So

it just seems extraordinary to me that such an equivocal person and such an

equivocal filmmaker should excite, you know, such extreme reactions from

people.

GROSS: Anthony Minghella directed "The English Patient" and "The Talented Mr.

Ripley." "Ripley" is now out on video. I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH

AIR.

(Credits given)

GROSS: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

Coming up, the creator of the X-Men, Spiderman and the Incredible Hulk and

many other comic book superheroes, Stan Lee. He's the executive producer of

the new "X-Men" movie, which opened today. Also film critic Henry Sheehan

reviews "Chuck and Buck."

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Filler: By policy of WHYY, this information is restricted and has

been omitted from this transcript

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.